I recently came across a fascinating new book about the French writer Irene Nemirovsky. The Nemirovsky Question by the Harvard academic Susan Rubin Suleiman traces the fascinating and complex story of the author’s life, against a backdrop of French literary culture, emigre culture and secular Jewish culture. Nemirovsky was born in Kiev in 1903, the daughter of a successful Jewish banker. Her father’s family came from the Ukrainian city of Nemirov, an important centre of the Hassidic movement in the 18th century, where they had become successful grain traders. In 1918 the Nemirovskys fled revolutionary Russia for France, where they assimilated into French high society and Irene became a successful novelist. Prevented from publishing when the Germans occupied France in 1940, she moved with her husband and two small daughters from Paris to the relative safety of the village of Issy-l’Eveque. She died in Auschwitz in 1942. Nemirovsky’s background closely mirrors my own. My grandmother was born near Kiev in 1902, also to a family of grain traders. And like the Nemirovskys, my family was closely linked to Hassidism – my great-great-great grandfather was a special advisor to one of the sect’s most famous Rabbis, Reb Dovidl Twersky. Perhaps it was fate that took the Nemirovskys to France after the Revolution. They had initially fled to Finland, then Sweden. And maybe it was just luck that my family came to Canada. A cousin had ended up in Winnipeg before the revolution and much of the rest of the family followed over the next 20 years. And so my grandmother’s fate and that of Irene Nemirovsky were, mercifully, different. Nemirovsky started writing Suite Francaise, her most famous work to contemporary readers, in 1941, based on the events taking place around her. In her writing, she denounced fear, cowardice, acceptance of humiliation, of persecution and massacre. She had no illusions about the attitude of the inert French masses, nor about her own fate. She realised that her situation was without hope. When Nemirovsky was arrested and deported, her husband, Michel Epstein, did not understand that this would mean almost certain death. He expected her to return, and petitioned the authorities for her release on the grounds of poor health. He too was arrested and died in Auschwitz. Miraculously, their daughters survived, having fled with their governess and lived in hiding for the remainder of the war, taking their mother’s manuscript with them from one hiding place to another. In 2006 I happened to meet a charming middle-aged French couple while on holiday in France. When talking to them about my book, A Forgotten Land, the story of my grandmother’s early life in Russia in the early 19th century, they began to tell me about close friend of theirs called Denise, the daughter of a Jewish woman who had died during the holocaust. Denise had kept her mother’s wartime diary as a memento, but had found it too painful to read until decades after the war, when she discovered it was not merely a diary, but a powerful literary masterpiece. “Is this the daughter of Irene Nemirovsky?” I asked. They were surprised that I knew of her; the book had been published in French two years earlier, and in English only that very year. For my part, I felt privileged to have met friends of Nemirovsky’s daughter, and so soon after reading Suite Francaise, when its horrors and brilliance were still so fresh in my mind.

0 Comments

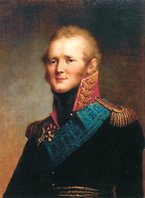

I was interested to read this week that the Israeli government is planning to discuss once again the fate of the so-called Subbotniks living in Russia and Ukraine, descendants of Russian peasants who converted to Judaism over 200 years ago. The Subbotniks have been oppressed on two fronts – persecuted at home for being Jews, but recently considered insufficiently Jewish to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. Israel’s committee on immigration and absorption is due to debate the issue of the Subbotniks soon, and many members of the community are hoping for a ruling in their favour that will enable them to join family members already in Israel. The origins of the Subbotniks are hazy. They date back to the late 18th century, during the reign of Catherine the Great, when a group of peasants in southern Russia distanced themselves from the Russian Orthodox Church and began observing the Jewish Sabbath – hence their name, derived from the Russian Subbota (Суббота), meaning Saturday, or Sabbath. Their descendants celebrate Jewish holidays, attend synagogue and observe the Sabbath. But it is not clear whether their forefathers officially converted to Judaism, and once in Israel, Subbotniks are still considered non-Jews until they undergo conversion. Many do not recognise the term Subbotnik – they consider their families to have been Jewish for many generations, and have been persecuted for their faith – and cannot understand Israel’s position. In the early 19th century, Tsar Alexander I (see photo) deported the Subbotniks to various parts of the Russian empire, leaving small communities scattered across a wide area. For this reason, Subbotniks today can be found as far apart as Ukraine, southern Russia, the Caucasus and Siberia. A first wave of Subbotnik emigration took place in the 1880s, when many fled persecution to settle in what was then part of Ottoman Syria, now Israel. Anti-Semitic pogroms broke out in Russia in the early 20th century, prompting another wave to emigrate. Many more Subbotniks left the Soviet Union and its successor states after the fall of the Berlin Wall, part of the more than million-strong flood of Soviet Jews who immigrated to Israel at that time. Some prominent Israelis are descended from Subbotnik settlers – among them former prime minister Ariel Sharon. But Israel’s Chief Rabbinate later claimed that the Subbotniks’ Jewish origins were not sufficiently clear, and that they would have to undergo conversion to Orthodox Judaism, thereby making them ineligible for aliyah to Israel – the automatic right to residency and Israeli citizenship that is available to all Jews. Some Subbotniks were granted the right to immigrate in 2014, but around 15,000 are estimated to still live in the former Soviet Union, most of whom desire to immigrate to Israel. The biggest Subbotnik community today is still in the area around Voronezh, where the movement began. It’s a city I know well, having spent a year as a student there in the 1990s.  Ukraine’s prime minister Volodymyr Groysman was in Israel this week, holding meetings with his Israeli counterpart Benjamin Netanyahu. The two are the world’s only Jewish prime ministers. “This is a moment of great friendship because there is a common history that binds Ukraine and Israel. Some of it is laced with tragedy, but it is also laced with hope and sympathy,” Netanyahu said. Around 500,000 of Israel’s 8.5 million inhabitants have roots in Ukraine. Many arrived during the early decades of the Jewish state, but the number of Ukrainian immigrants to Israel has surged since the war in the east of the country began. Since 2014, some 19,000 Ukrainians have made Aliyah, or moved to Israel. Every month or so, a chartered plane arrives carrying a few hundred more new immigrants. The story of 26-year old Alena Sapiro from Donetsk echoes that of many others. “In Ukraine, I had a flat, a job, a boyfriend, and a cat. I had everything. I finished university with two degrees. I started to study for a doctorate and wanted to be a teacher at the university. But then my university was bombed. My best friend was killed in the war, and my stepfather was also killed. My mother told me, ‘Go away from here,’” she told Tel Aviv-based journalist Larry Luxner. Valery Nevler, aged 24, says he left Ukraine just in time. “There was fighting in the streets. I got one of the last trains to Lviv [in western Ukraine] and a few days later the train station in Donetsk was hit by a missile attack.” He does not regret his move. In Ukraine, he says, “People’s salaries are not enough even to buy food, not to mention paying taxes and rent. So many people who are stuck in Donetsk would love to go to a peaceful place, but they don’t have money, so they stay.”* Netanyahu was not always so enthusiastic about Ukraine. Last year Ukraine supported a UN resolution condemning Israel’s settlement policies in the West Bank and Netanyahu cancelled Groysman’s planned visit in December 2016, straining relations between the countries. Groysman came to power last year, becoming Ukraine’s first Jewish prime minister. He was born in 1978, so avoided the toughest constraints inflicted on Jews by the Soviet regime. Despite the growing nationalism in Ukraine that has prompted a rise in anti-Jewish attacks, Groysman dismisses assertions of widespread anti-Semitism. “Ukrainian citizens have a good will and are nice people. Ukraine is my country. It’s a great honour to be a citizen and born in Ukraine,” he said during his visit to Israel. Of his Jewish background, Groysman says, “I believe it would be humiliating to hide someone’s roots, to hide someone’s family or last name.” He stressed the close relations between Kiev and Israel and emphasised that the world should stand on the side of democratic Ukraine against Russian aggression. *Interviews published by the Atlantic Council The Jerusalem Post yesterday published an amazing story about the small town of Bershad, dubbed ‘Ukraine’s last shtetl’. Described as a “drab town 160 miles south of Kiev”, Bershad is located due south of Pavolitch (Pavoloch in Russian), where my family originates, close to the present-day border with Moldova. Its population numbers some 13,000, around 50 of whom are Jewish.

The town initially appears no different from hundreds of other grim Ukrainian towns where a handful of ageing Jews try to keep their traditions alive. My father and I experienced several similar settlements when we were in Ukraine in 2005 to visit our ancestral home and carry out research for A Forgotten Land. We were shocked, in particular, to find that the tiny Jewish community in Makarov – home to a famed dynasty of Twerksy Rabbis, and also to my great-grandfather Meyer – had no idea where the renowned Rabbi’s Court had stood. All were incomers who had not known Makarov before the Second World War. But Bershad is clearly different, “a living testament to the Jewish community’s incredible survival story – one that has endured despite decades of communist repression, the Holocaust and the exodus of Russian-speaking Jews”. In marked contrast to the region’s other Jewish communities – in fact to religious communities of any faith, which were harshly persecuted in the Soviet era – the authorities returned the town’s synagogue to the Jewish population in 1946, after the Nazi’s were defeated. While most shtetls were wiped out by the Nazi invasion (the Jews of Pavolitch were rounded up and shot in 1941), Bershad survived owing to its westerly location, which put it under the occupation of Romanian, rather than German, troops during the war. The Romanians were less systematic in their slaughter of Jews. They liquidated neighbouring shtetls, but Bershad (with a pre-war Jewish population of 5,000) became a Jewish ghetto with a population of 25,000. The majority perished, but after the war, some 3,500 remained. In the post-war era, the community attributes the shtetl’s survival to centuries of coexistence with the gentile population. Bershad’s Jews were workers – metal workers, shoemakers, carpenters and fishermen – whose families had worked alongside non-Jews for generations. Unlike in larger towns, they were not regarded as class enemies, such as intellectuals or merchants. Bershad’s elderly Jewish population recalls following the traditional rituals and festivals, with the smell of baking wafting from the makeshift matza bakery before Passover and families gathering outside the synagogue to hear the shofar on Yom Kippur. Most of Bershad’s Jews have emigrated to the US or Israel since the Soviet Union collapsed and exit visas became freely available. The matza bakery has closed; the synagogue is more of a community centre and rarely achieves a minyan; and what remains of the Jewish quarter is disintegrating following a quarter of a century of emigration. The last remaining native Yiddish speaker is considering leaving for Israel. But the fact that Bershad’s Jewish community survived as long as it did is a miracle in itself. How ironic that US President Donald Trump should choose Holocaust Memorial Day to unleash his latest executive order, banning refugees, and in particular Muslims, from seven countries - Syria, Iraq, Iran, Libya, Somalia, Sudan and Yemen – from entering the US for 90 days. This was a first step towards a broader ban, a spokesman said.

It has been widely reported that no act of terrorism has been committed on US territory by people from these seven countries. I heard the news on the car radio the following morning and felt so angry I could barely speak, angry and scared. This is how it begins – isolating and discriminating against a group of people solely on the basis of their religion. Public attitudes towards that group of people harden, attacks take place, the screw tightens further. The cycle has begun. Look where it ended up in Europe in the last century. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, nearly three million Jews left the shtetls of Eastern Europe, the majority of them heading for America, and many of them refugees – victims of pogroms, anti-Semitism, and after the Russian Revolution of 1917, government discrimination. In 1924, the US closed the gates, with the intention of halting the flow of refugees from Eastern Europe. Even in 1939 when European Jews were being herded into ghettos, the US turned away the MS St Louis carrying 900 Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. In the 1930s and 1940s, people did not speak out, certainly not in sufficient number. History obliges all of us, and Jews in particular, to speak out against Trump’s Muslim Ban. Martin Niemoller’s poem, which has numerous versions, is as important today as it was when it was written in the 1940s. First they came for the Jews and I did not speak out because I was not a Jew. Then they came for the Communists and I did not speak out because I was not a Communist. Then they came for the trade unionists but I did not speak out because I was not a trade unionist. Then they came for me and there was no one left to speak out for me. My grandmother grew up in the small town of Pavolitch (Pavoloch in Russian), about 60 miles southwest of Kiev. Around a third of the population of Pavolitch was Jewish at the beginning of the 20th century. Between 1880 and 1924, hundreds of thousands of Jews abandoned the region, as violent anti-Semitic pogroms swept the area known as the Pale of Settlement, the old Polish lands where Jews were confined to living under the Tsars. The bloodiest pogroms took place in 1881 and 1905, each prompting its own exodus. A majority fled to America, but sizeable numbers settled in Canada, the UK and elsewhere. My grandmother fled to Winnipeg, Canada, in 1924, joining her brother, great uncle and cousins who had already made the journey. By 1929, most of her close family had joined her in the Free World.

Almost all Jews who remained in the territory of the Pale after the Nazi invasion of 1941 were slaughtered, most of them shot at mass graves that they were often forced to dig themselves. Some, with great prescience, escaped to the east, to the Urals or Central Asia, and returned only once the war was over. The end of the Soviet era led to another mass wave of Jewish emigration. Between 1989 and 2006, about 1.6 million Jews and their non-Jewish partners and families emigrated from the former Soviet Union. The majority, or close to a million, settled in Israel, but sizeable minorities went to the US and Germany. Among those starting a new life in Germany were several of my relatives, who left Kiev and Odessa keen to rid themselves of a lifetime of anti-Semitism at home and a new brand of lawlessness that had taken hold when the Soviet power structures were toppled. The war in the east of Ukraine since 2014 has prompted another wave of emigration. The fighting has killed more than 9,000 people in the last two years. Around 2,000 have fled the region’s cities, in particular Donetsk, which has come under heavy shelling from the Ukrainian army since it was taken by pro-Russian separatists in April 2014. The Jewish population of Donetsk has dropped from 10,000 to just a few hundred. Some 7,200 Jews fled Ukraine for Israel in 2015, up from 2,000 in 2013. Many more have moved across the border to Russia, and others are living elsewhere in Ukraine. Not regarded as refugees as they remain in their own country, many of them eke out a meagre existence, sleeping on the floors of friends and family, or being supported by international Jewish aid organisations. Around 200,000 Jews are estimated still to live in Ukraine today. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed