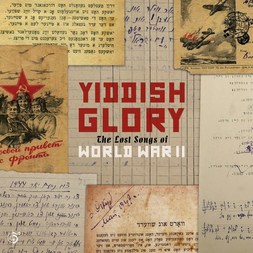

A few years ago, a hoard of songs written by Jewish men, women and children killed in World War II came to light in Kiev. The songs, in Yiddish, are haunting, raw and emotional testimonies by ordinary people experiencing terrible events. They are grassroots accounts of German atrocities against the Jews, with subjects that include the massacres at Babi Yar and elsewhere, wartime experiences of Red Army soldiers, and those of concentration camp victims and survivors. One song was written by a 10-year old orphan who lost his family in the Tulchin ghetto in Ukraine, another by a teenage prisoner at the Pechora concentration camp in Russia’s far north. The songs convey a range of emotions, from hope and humour to despair, resistance, and revenge. The project to collect these songs is as remarkable as the music itself. It began when a group of Soviet scholars from the Kiev cabinet for Jewish culture, led by the ethnomusicologist Moisei Beregovsky (1892-1961), made it their mission to preserve Jewish culture in the 1940s. They recorded hundreds of Yiddish songs written by Jews serving in the Red Army during the war; victims and survivors of Ukrainian ghettoes and death camps; and Jews displaced to Central Asia, the Urals and Siberia. Beregovsky and his colleagues hoped to publish an anthology of the songs. But after the war, the scholars were arrested during Stalin’s anti-Jewish purge and their work confiscated. The story could so easily have ended there; indeed the researchers went to their graves assuming their work had been destroyed. Miraculously the songs survived and were discovered half a century later. They were discovered in unnamed sealed boxes by librarians at Ukraine’s national library in the 1990s and catalogued. Then in the early 2000s Professor Anna Shternshis of the University of Toronto heard about them on a visit to Kiev and brought them to light. Some were typed, but most handwritten, on paper that was fast deteriorating. Most consisted just of lyrics, although some were accompanied by melodies. The songs were performed for the first time since the 1940s at a concert in Toronto in January 2016, and are shortly to be released by record label Six Degrees. Artist Psoy Korolenko created or adapted music to fit the lyrics, while producer Dan Rosenberg brought together a group of soloists, including vocalist Sophie Milman and Russia’s best known Roma violinist Sergei Eredenko, to create this miraculous recording. “Yiddish Glory gives voice to Jewish children, women, refugees whose lives were shattered by the horrific violence of World War II. The songs come to us from people whose perspectives are rarely heard in reconstructing history, none of them professional poets or musicians, but all at the centre of the most important historical event of the 20th century, and making sense of it through music,” Shternshis says. Yiddish Glory: The lost songs of World War II will be released on 23 February. For more information see: https://www.sixdegreesrecords.com/yiddishglory/

0 Comments

My first blog post of the new year is inspired by a passage written by the Russian Jewish author Isaac Babel, which I came across while doing research for a new book that I am starting this year. Babel was born in Odessa, in present-day Ukraine. He initially embraced the Russian Revolution, welcoming the new freedoms that Jews experienced under the Bolsheviks – the Pale of Settlement, where Jews were confined to living under the Tsars – was dissolved, quotas for schools, universities and professions were abolished and censorship ended. Like many other artists and writers, Babel became an ardent Bolshevik, but found himself increasingly out of favour during the rule of Joseph Stalin, who led the Soviet Union from 1924. Stalin promoted the bland Socialist Realist artistic style and the exciting, experimental art and literature of the immediate pre- and post-revolutionary years was brutally supressed. Unwilling to leave Mother Russia and follow his wife and daughter into exile in Paris, Babel was eventually shot in 1940, during Stalin’s purges, following a brief show trial. His name and work were erased in the Soviet Union until 1954, when he was rehabilitated during the so-called ‘thaw’ under Nikita Khrushchev. The passage below is a wonderful illustration of the contradictions that people – perhaps Jews especially – felt about the revolution. It comes from the short story Gedali, which forms part of Babel’s Red Cavalry collection. The Red Cavalry stories describe snapshots from Babel’s experience as a war correspondent during the 1920 campaign by the newly formed Soviet Red Army to invade Poland and spread socialist revolution to neighbouring countries. We sit down on some empty beer barrels. Gedali winds and unwinds his narrow beard. His top hat rocks above us like a little black tower. Warm air flows past us. The sky changes colour – tender blood pouring from an overturned bottle – and a gentle aroma of decay envelops me. “So let’s say we say ‘yes’ to the Revolution. But does that mean that we’re supposed to say ‘no’ to the Sabbath?” Gedali begins, enmeshing me in the silken cords of his smoky eyes. “Yes to the Revolution! Yes! But the Revolution keeps hiding from Gedali and sending gunfire ahead of itself.” “The sun cannot enter eyes that are squeezed shut,” I say to the old man, “but we shall rip open those closed eyes!” “The Pole has closed my eyes,” the old man whispers almost inaudibly. “The Pole, that evil dog! He grabs the Jew and rips out his beard, oy, the hound! But now they are beating him, the evil dog! This is marvellous, this is the Revolution! But then the same man who beat the Pole says to me, ‘Gedali, we are requisitioning your gramophone!’ ‘But gentlemen,’ I tell the Revolution, ‘I love music!’ And what does the Revolution answer me? ‘You don’t know what you love, Gedali! I am going to shoot you, and then you’ll know, and I cannot not shoot, because I am the Revolution!’” “The Revolution cannot not shoot, Gedali,” I tell the old man, “because it is the Revolution.” “But my dear Pan! The Pole did shoot, because he is the counterrevolution. And you shoot because you are the Revolution. But Revolution is happiness. And happiness does not like orphans in its house. A good man does good deeds. The Revolution is the good deed done by good men. But good men do not kill. Hence the Revolution is done by bad men. But the Poles are also bad men. Who is going to tell Gedali which is the Revolution and which the counterrevolution? I have studied the Talmud. I love the commentaries of Rashi and the books of Maimonides. And there are also other people in Zhitomir who understand. And so all of us learned men fall to the floor and shout with a single voice, ‘Woes unto us, where is the sweet Revolution?’” |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed