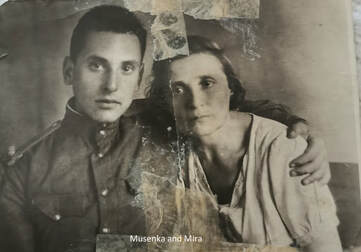

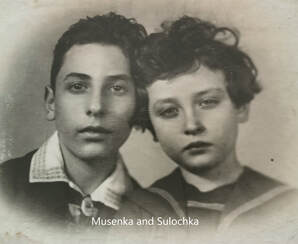

The Soviet Union was not an easy place to live after World War II, and especially for Jews. Those who managed to survive the war by fleeing to Central Asia or the Urals and returned after the German retreat found their homes destroyed, their towns devastated, and their Jewish neighbours slaughtered. In Kiev, then in Soviet Ukraine, where several members of my family lived, nearly 34,000 Jews had been shot at the ravine known as Babi Yar on the edge of the city on 29-30 September 1941. But this was far from the only anti-Semitic atrocity committed by the Nazis in the city. My grandmother’s first cousin Baya was among a group of Jews herded to the banks of the river Dnieper and forced aboard a ship that was set alight. There were no survivors. And few rural Jews from the villages formerly known as shtetls survived the war either. In Pavoloch, my grandmother’s home town, on 5 September 1941 up to 1,500 Jews were shot beside a mass grave dug in the Jewish cemetery. The victims came from many outlying villages as well as Pavoloch, herded to the town for slaughter. The terrible event has become known as the Pavoloch Massacre and even featured in last year’s Amazon Prime series Hunters, which I found myself unable to watch. Several hundred thousand Jews fled to the eastern republics of the Soviet Union in 1941 as the Nazis approached. You can read some of their stories here. Many never went back to the towns they had left, unable to contemplate returning to places where such terrible devastation had taken place. Most, inevitably, would have lost family members or friends to the Nazis. It is hardly a surprise that a great number emigrated to Israel or the United States as soon as the possibility arose, while some remained in Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan, or elsewhere. But thousands of Jews did return to their homes in towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. In my last article I wrote about my grandmother’s aunt Miriam (Mira) and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka), who made it back from Central Asia to Kiev in December 1943. Mira’s son Moishe (Musenka) had been called up earlier the same year to a military academy in Turkmenistan, on the Afghan border, and did not come home with them. To continue their story, in 1944, Musenka was transferred to the front – to Poland. In preparation for his departure, he was moved to an army camp on the outskirts of Kiev, where his mother and sister were able to visit him. Later, from Poland, Musenka wrote that his regiment was preparing for a major offensive in Warsaw. He died on 16 October 1944, ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s final offensive to liberate the Polish capital. He was 18 years old. It was his sister Sulochka, rather than his mother Mira, who received the death notice sent by the Soviet military authorities. Sulochka was 13 and had become something of a tearaway – a fiercely independent girl who skipped lessons and swiped pastries from vendors at the old Jewish market. She hid the letter from her mother, knowing how deeply it would upset her. But Musenka had been a loyal son and always kept in touch regularly with his family. Mira descended into a panic after his letters stopped. She contacted the military authorities searching for information, but when a second copy of the death notice arrived, once again it was Sulochka who intercepted it. Mira wanted to die. She felt she couldn’t live without her precious only son and couldn’t bear not knowing what had happened to him. She returned to the ruins of her pre-war home in the hope that bricks from the half-demolished building would fall and kill her. She more or less ignored her living daughter, Sulochka, amid the pain she felt over her missing son. Her husband Yehuda – exiled to a labour camp near Krasnoyarsk – even wrote a letter to the war commissar Klim Voroshilov with a plea for help in finding any trace of Musenka. Many families waited years, decades even, for their menfolk to return from the war. Some were lucky; many were not. As time passed, the small glimmer of hope that her son was still alive and would one day come home gave Mira the strength to go on living. It was not until 1964, twenty years after Musenka’s death, and after Yehuda – finally liberated from the gulag – had also passed away, that Sulochka confessed to her mother that she had hidden the letters from the military authorities informing them that her brother had died in action. In the end, knowing the truth at last helped ease Mira’s distress. For all those years she had tormented herself with the thought that Musenka might have fallen into the hands of the Banderovtsy – the anti-Semitic Ukrainian nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, who allied with the Nazis and collaborated in the near-total destruction of Jewish life in Ukraine. The torture they inflicted on captured Red Army soldiers was notorious, and all the more so for those of Jewish descent. Mira spent her post-war years enveloped in grief over the loss of her beautiful boy – and yes, photographs testify that he was indeed beautiful. Her love for her daughter remained in the background; it clearly existed, but was rarely overtly demonstrated. Mira could be a stubborn and awkward character and she and Sulochka were often at loggerheads. But Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was 14 when Mira died in 1966, remembers her with warmth and affection. This story will be continued in my next article.

0 Comments

Soviet Jews that survived World War II by fleeing eastwards found a tough life waiting for them on their return home to towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. I wrote recently about the experiences of several Jewish families as refugees in Central Asia during the war, including my great-grandfather’s sister, Miriam (Mira) – you can read that article here. Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was born in Kiev after the war and lived there until the 1990s, has shared with me her family stories of life back in that city after the return from Central Asia. The family had lived before the war in the centre of Kiev, at 37 Pushkinskaya Street in a communal apartment – one room for each family, with shared cooking and washing facilities, as was typical of Soviet life during the era of Stalin and Khrushchev. Sometimes a family occupied just a section of a room, partitioned off with a curtain. On their return from Central Asia after the Nazi retreat in late 1943, Mira and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka) – Ira’s grandmother and mother – made their way from the station on foot – no public transport was running – through the ruins of the devastated city, to find out what had become of their home. They found the four walls still standing, but nothing more. The building was restored after the war and exists to this day. “Whenever I go back to Kiev, I always wander around the courtyard and look up at the balcony, as if I’m looking for my mother as a little girl,” Ira says. A quick Google search shows an attractive four-story building on a tree-lined street, next door to a “hip Israeli eatery” called Pita Kyiv and just down the road from the Estonian embassy. As Ira’s mother and grandmother stood weeping before their ruined home, a figure approached them – a woman they had been acquainted with before the war. Knowing what had happened to the Jews of Kiev at the end of September 1941, when 34,000 were shot at the ravine of Babi Yar on the edge of the city, the woman took pity on Mira and Sulochka. She led them back to her basement flat on Saksaganskaya Street, a mile or so away, and invited them to stay. There Mira recognised many of her own possessions and those of her neighbours, stolen when they had departed in haste during the evacuation of the city. Mira said nothing. She was grateful simply to have a roof over her head. Every day Mira returned to her building on Pushkinskaya in the hope of meeting the postman, desperate for news from her son Moishe (Musenka) in the army, and her husband Yehuda in the gulag. And she petitioned the authorities for a place to live for herself and her daughter. For once she was lucky, and was assigned a room in a communal apartment, but at the expense of another family, who were forced onto the street. The dispossessed family rushed at Mira and beat her in anger and despair at losing their home. With so much of the city destroyed and more evacuees returning by the day, the authorities would juggle the accommodation that was still standing, taking shelter from one family to give to another; a lottery of relief or desolation. The room was ten metres square, with no running water or sewerage. Later it became smaller still, with three meters reapportioned to create a corridor where a cooker was installed. But it was a roof over their heads and it was precious. In this room, nearly a decade later, Ira was born. How Mira found the means to live during this period, Ira doesn’t know. But she suspects it was Mira’s brother, Uncle Avrom, who came to their rescue, as he had during the evacuation of Kiev, finding transport for them and a place to live. Sulochka also told Ira about her cousin Beba. Ira says Beba’s real name was Volf. According to the family tree my grandmother and father drew up he was called Velvl, while his grandson – who now lives in Germany – refers to him as Vladimir. Such are the complications of Jewish genealogy! Cousin Beba was the only relative that did not turn against Mira when she became the wife of an Enemy of the People, after her husband was arrested in 1938 and sent to the gulag. One day Beba visited and saw that Sulochka had grown out of all her warm clothes, and in the dead of winter. He went to the crowded flea market where people bought and sold new and second-hand goods and found her a pair of warm boots. Mira continued to go back to the family’s old home on Pushkinskaya in the hope of seeing the postman and finding a letter from her son or husband. In 1944, Musenka wrote that he was being transferred to the front – to Poland – and that before his departure he would be based at a large camp on the outskirts of Kiev, by the Darnitsia train station across the river Dnieper. Mira and Sulochka were able to visit him there. Musenka was 18 years old and this was the last time his mother and sister ever set eyes on him. This story will be continued in my next article. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed