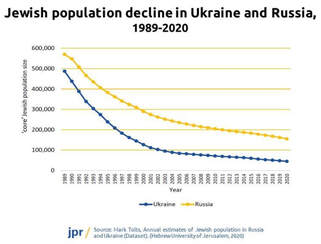

Since February 2022, more than six million Ukrainians have fled abroad in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Another 8 million are internally displaced, mostly in western Ukraine. And around a million Russians have also escaped abroad, many because of their opposition to the war or to avoid the draft under Russia’s partial mobilisation. Among these numbers are tens of thousands of Jews. According to Israel’s Ministry of Aliyah and Integration, more than 40,000 immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus in the year to February 2023. Many members of the Ukrainian Jewish community have also found refuge in other European countries, but those who arrived in Israel held an advantage in having an immediate right to citizenship. The number of Ukrainians with at least one Jewish grandparent – and therefore qualifying for Israeli citizenship by Israel’s Law of Return – was 200,000 in 2020, according to the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR), while the number who identify as Jewish (the ‘core’ Jewish population) was estimated at 45,000. Since the end of the Cold War, the Jewish population of Russia and Ukraine has fallen by 90%, according to the JPR, continuing an exodus that had begun in the early 1970s. An easing of the ban on Jewish refusenik emigration from the Soviet Union at that time allowed approximately 150,000 Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a further 400,000 departed, with more than 80% heading to Israel and the remainder mostly to Germany and the US – several members of my own family among them. In 2014, the number of Ukrainian Jews immigrating to Israel jumped by 190% in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine. Jewish emigration from Russia also spiked and the numbers coming to Israel from both countries stabilised at this higher level in the eight years leading up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With another war now raging in the Middle East, some of those displaced by the hostilities in Ukraine have had to flee twice over. Among them are more than sixty children from the Alumim children’s home near Zhytomyr in western Ukraine. Some are orphans from the surrounding towns and villages within the historic Pale of Settlement, others have parents who are unable to provide a stable home for them. On 24 February 2022, bombs began to fall around the home, which was located close to a Ukrainian air base. Its founders, Rabbi Zalman Bukiet and his wife Malki, had made advance preparations in case of a Russian attack and were able to quickly evacuate the children to the west of the country by bus. After a few days, when it became clear that the war would not reach a swift conclusion, they crossed the border into Romania and from there boarded a plane to Israel. The logistics of the transfer were complex as almost none of the children had passports. Some of their mothers and other community members joined the group until it numbered 170 people. “El Al Airlines wanted us to finalise the number of seats we needed, and the paperwork was an open question,” Rabbi Bukiet recalled. One child had been away visiting his home village when the war broke out and had to be driven to Romania by taxi for a fare ten times higher than the standard rate. Once in Israel, the group was hosted at the Nes Harim education centre in the Jerusalem Hills. “We came for a month and stayed for six,” Rabbi Bukiet said. But as the new school year came round, he needed to find a more permanent home for the children. The group moved to Ashkelon, a coastal town in southern Israel, and rented two accommodation buildings – one for girls and one for boys – as well as apartments for the 16 families that had come with them from Zhytomyr and a home for the rabbi and his own family. “And so Ashkelon became home. The kids learned Hebrew, gained Israeli friends and integrated into the local community. The mothers took jobs and learned to navigate life in Israel. And we all got used to the new normal,” Rabbi Bukiet said. He and Malki arranged visits for a family member from Ukraine for each child, along with outings and activities. With the next school year due to begin, the group decided to stay another year in Ashkelon. Until history repeated itself. On 7 October the sirens once again blared at six am, just as they had in Zhytomyr 18 months or so earlier. Once again, the sound of gunfire and explosions reverberated around them. Rabbi Bukiet and his own family ran to a shelter but were unable to reach the children’s dormitories until midday. By the afternoon, the constant sirens had eased the he and Malki were able to gather the children together in a larger shelter. That night they made plans to relocate again, further north into Israel. Today the inhabitants of the children’s home are based in the Hasidic village of Kfar Chabad, not knowing how long they will stay. Safe for now, their future is uncertain once again. The full story of the Alumim children's home can be found here: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/6186434/jewish/How-Our-Childrens-Home-in-Ukraine-Was-Uprooted-Again-by-War-in-Israel.htm

0 Comments

When Hamas terrorists entered southern Israel last month, they committed the biggest mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust. That on its own is a desperately chilling thought. But Israel’s response to the attacks has unleashed a wave of antisemitism around the globe on a scale not seen since the middle of the last century. Words that for decades have been unsayable in public are now being chanted in the streets of our major cities. And in Russia, a country with a devastating history of antisemitism that had until recently been quashed, pogroms have broken out once again. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jews in Russia suffered wave after wave of pogroms – anti-Jewish riots that involved terrorising communities, attacking Jewish homes and businesses, humiliating and maiming, rape and murder. Last weekend Russia witnessed its first pogrom in sixty years. In Dagestan, a mainly Muslim region of southern Russia bordering Chechnya, an angry mob shouting antisemitic slogans stormed the airport of the regional capital Makhachkala. The rioters broke through security barriers onto the runway with the intention of attacking passengers arriving from Tel Aviv, fuelled by rumours circulating on social media that the plane was carrying refugees from Israel. The rumours were later proven to be untrue. Elsewhere in Dagestan, a riot broke out outside a hotel in the city of Khasavyurt, because Israeli refugees were believed to be sheltering inside. The protestors pinned a sign to the door: Entry strictly forbidden to Israelis (Jews). And in Nalchik - located, like Dagestan, in the North Caucasus region - a mob attacked and set alight a Jewish cultural centre that was under construction. The words Death to Jews were daubed on its wall. These events took place in spite of strict rules prohibiting public demonstrations in Russia, implemented to stifle protest against the war in Ukraine. The pogroms of the past took place across the Pale of Settlement, where Jews were restricted to living in Tsarist times – in present day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and the western fringes of Russia. These regions had been absorbed by Russia during the partitions of Poland under Catherine the Great in the late 18th century. Jews had long been present in great numbers in Poland because its liberal policies contrasted with most other parts of Europe at the time; Jews were welcomed for their skills in commerce that helped bolster the economy. But Russia was far less tolerant and pogroms were a direct result of an official policy of antisemitism. Today’s pogroms in Dagestan derive from sympathy with Palestinians under Israeli bombardment in Gaza. With a mostly Muslim population, Dagestan has historically been more closely aligned with the Middle East than with Russia. But it is also home to Russia’s oldest Jewish community. Jews have lived in the region since Biblical times and as Jews from elsewhere in Russia have emigrated in huge numbers, mostly to North America and Israel, Dagestan today is home to Russia’s largest Jewish community. Just as the pogroms of the past were a manifestation of official antisemitism in the Russian Empire, the pogroms in Dagestan reflect a change in sentiment in the echelons of power in Moscow. While the Vladimir Putin of the past spoke out against holocaust denial and xenophobia, the Russian president has in recent months ratcheted up antisemitic rhetoric as a reaction to Russia’s failings in the war in Ukraine, not least with his derogatory comments about Ukraine’s Jewish president Volodymyr Zelensky (see my article on the subject here). Putin’s reaction to the violence in Dagestan has been to blame Ukraine and the West, accusing Russia’s enemies of fomenting unrest to destabilise the country. The violence in Dagestan continues a worrying trend for Putin, demonstrating again how his authority is being undermined. Having risen to power almost a quarter of a century ago, Putin cemented his popularity with a reputation for restoring Russia’s territorial integrity and stability after the chaotic unravelling of the 1990s. It was his quelling of violence in Dagestan and neighbouring Chechnya that helped reinforce the strongman image that the president has sought to project ever since. But Putin’s obsessive focus on trying to destroy Ukraine has led him to turn a blind eye to unrest in Russia’s provinces that threatens to undermine his reputation and the sense of order and stability that he has so painstakingly nurtured. The attempted mutiny in June by his once loyal ally Yevgeny Prigozhin was the first clear manifestation of Putin’s authority beginning to unravel. Unrest in the North Caucasus may be the next. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed