Most Jews in North America and much of Europe can trace their roots back to the Russian Empire, once home to the world’s largest Jewish population. But how many of us actually understand how our families ended up there in the first place? The basics are fairly well known. After the Roman sacking of Jerusalem in 70AD, Jews scattered across the Roman Empire, which covered most of southern and western Europe and north Africa. By the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, the Jewish diaspora had spread right across Europe. The split into two distinct communities: the Sephardi on the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazi along the Rhine in Germany occurred around the 10th century. During the Crusades in the 13th-15th centuries, Jews were expelled from much of western Europe, including from England in 1291, France in 1343 and much of western Germany in the early 15th century. Many fled east, to the one country that offered a safe haven for Jews – Poland. Here King Casimir the Great (reigned 1333-1370) welcomed Jews for their trades and skills and protected them as “People of the King”. But by the 18th century, Poland was a weak and failing state, preyed on by its more powerful neighbours: Prussia, Austria and Russia. These three great European powers divided the country up between them in the three Partitions of Poland of 1772, 1793 and 1795. The area to the southwest of Kiev where my family came from became part of the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great in the second partition of 1793. Since 1991 it has been in independent Ukraine. Bert Shanas, a retired journalist turned genealogist from New York, has traced his family history to shtetls southwest of Kiev from at least the mid-1600s, and it is from his research that I have borrowed the contents and title of this article. The typical Ashkenazi Jew from this region, Shanas says, has an ancestral line that began in Africa, migrated to the Middle East, and from there into Europe, through France, to present-day Germany and into Poland, to an area that went on to become Russia then Ukraine over the course of some 200,000 years. Using a combination of DNA testing, recent scientific studies, archaeological discoveries, and biblical and historical scholarship, Shanas has traced the likely route his ancestors would have taken. His male family line would have had its origins in east Africa 60,000-70,000 years ago – around present-day Ethiopia, Kenya or Tanzania. Major climatic changes would probably have forced his ancestor to journey to the northeast in search of an adequate food supply, most likely travelling in a group of around 200 people. They would have crossed the Red Sea – then a smaller, shallower channel – into present-day Saudi Arabia and continued eastwards along the coast of the Arabian Sea until they reached the Indus Valley, the area that is today Pakistan. Thousands of years later, it is likely his ancestors would have broken off from the group and headed north through Iran to settle in what is now Turkey, around 40,000 years ago. About 10,000-15,000 years ago, they would have moved on to the Middle East, where Jewish history began – with Abraham, who came from the city of Ur in Babylonia, now southern Iraq - around 3,200 years ago. Shanas believes that following the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, his ancestors would probably have travelled from the Middle East through Turkey, Greece and Italy, then north through France around the year 1400 and from there to Germany. Around 1500, they would have moved east again, into Poland and by 1600-1700 were settled in the area near Kiev. DNA analysis indicates that Shanas’ female family line probably ended up in Poland by a different route, trekking north from the area around present-day Kenya or Ethiopia around 60,000 years ago, through Sudan and Egypt into the Middle East. They would have survived the last Ice Age somewhere around Mediterranean Europe and once the glaciers retreated, spread throughout Europe between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago. His ancestral line would probably have migrated to the Caucasus mountains then arced over the Black Sea into the Balkans. From there the DNA trail branches in two directions, the first heading north into Finland, passing through Poland on the way, and the second going west along the Mediterranean through France and Spain, into Portugal. DNA analysis shows that his genetic female ancestors were not grouped in great numbers in any one spot, but were scattered across eastern and western Europe, and their exact route to Ukraine is unclear. A study of the origins of Ashkenazi women by Professor Martin Richards at the University of Huddersfield in the UK and cited by Shanas in his research, found that in at least 80% of the cases studied, the DNA of Jewish women traced back to Europe – unlike that of men, which traced back to the Middle East. Richards concluded that the vast majority of Jewish men who fled the Middle East for Europe after the Roman conquest did not take women with them. Instead, they married local European women, who then converted to Judaism. With grateful thanks to Bert Shanas for allowing me to use his research for this article.

0 Comments

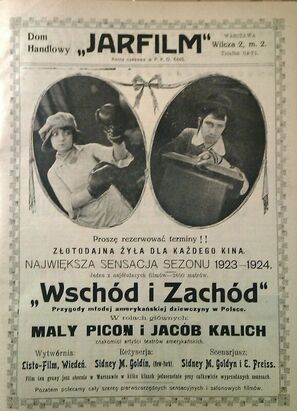

Old movies can tread a fine line between feeling dated and irrelevant, and providing a fascinating insight into a time and place that is long gone. Ost und West (East and West) is the earliest surviving example of Yiddish cinema, shot almost a century ago, in Vienna in 1923, and most definitely falls into the latter category. The film deals with the thorny issue of assimilation that has troubled Jewish communities for hundreds of years, as a wealthy New Yorker and his boxing-enthusiast daughter return to the old country for his niece’s wedding in a traditional, observant household. The most fascinating aspect of the film for me was to see scenes of how our ancestors would have lived: how they dressed, what their houses looked like, the food they ate, their Sabbath table. The household is a relatively affluent one in cosmopolitan Galicia, but the images still resonate strongly for those of us with family ties further east. As well as being intriguing from a historical point of view, the film is, in parts, laugh-out-loud funny, even for a modern, sophisticated audience. It throws up some hilarious faux-pas by the worldly Americans as they encounter traditional shtetl life. Even the suitably obese father – who one assumes grew up in the Orthodox community – cannot find the right page or passage in his prayer book, while his daughter Mollie takes a novel to the Temple to stick inside hers, while the rest of the family prays fervently on Yom Kippur. Unable to cope with hunger during the long day of fasting, Mollie sneaks out of the synagogue to raid the fridge, stuffing her face with the meal intended for the family to break the fast, then hiding the leftovers under the table, to be discovered by the pet dog and cat! But Mollie’s playful disruptiveness ends up getting her into more trouble than she could have imagined as a mock wedding game becomes real and she finds herself accidentally married to a young, pale-faced yeshiva student. This scene has great resonance for me as my great-grandmother found herself in a somewhat similar situation. The educated and impeccably dressed daughter of an affluent grain merchant, she spent more of her time reading modern novels than the Torah, but was forced into an arranged marriage with a Talmudic scholar who had been brought up in a Rabbinical court. Her initial horror at the match eventually turned to affection, and my great-grandparents’ marriage worked out in the end, as did that of the fictional Mollie and Ruben in East and West. East and West is one of a great number of Yiddish films of the 1920s and 30s that entertained audiences on both sides of the Atlantic, although those made earlier than 1923 have not survived. New York was the main centre of the Yiddish film industry, enjoying a ‘golden age’ in 1936-39, when more than two dozen films opened, only for this to be curtailed abruptly by the onset of World War II. The films capture the language and lifestyle, as well as the values, dreams, and myths of the world of American Yiddish culture. Yiddish films were also made in Poland, Austria and Russia. Filmmaking was a direct offshoot of Yiddish theatre, which had played a significant role in the life and culture of Jewish immigrant communities for many decades, and many popular stage actors were later immortalised in film. Molly Picon, the female star of East and West, began her career in Yiddish theatre in Philadelphia at the age of six and was one of few stars of Yiddish stage and screen to cross over into the mainstream American film industry, notably playing Yente the matchmaker in the 1971 production of Fiddler on the Roof. East and West “breathes true Jewish character”, even though “it does not satisfy – one might say, thank God – high literary expectations,” wrote the Viennese journalist E G Fried at the time of its release. Fried also cited the authenticity of the musical accompaniment, which drew on Jewish folk motifs. How much of that music remains in the version of the film we can view today is not clear. It is a silent movie set to a musical score produced by Henry Sapoznik and performed by Peter Sokolow during the process of restoration. Like many works of Yiddish cinema, the film only survived in fragmentary versions, and was reconstructed by the Filmarchiv Austria, funded in part by the American Film Institute Film Preservation Program and the National Endowment for the Arts. The film is available to watch from Rarefilmm, the "Cave of Forgotten Films". You can find it on their Facebook page here https://www.facebook.com/groups/1177986749024623 by typing "East and West" into the Search box. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed