Warsaw is possibly the most fascinating city I have ever visited. Its glorious old market square, lined with Baroque-style merchants’ houses, rivals those of Krakow, Prague or Brussels. And yet Warsaw’s old town was reconstructed from scratch in the middle of the twentieth century. Somehow the knowledge that the colourful facades are mere decades rather than centuries old added to my appreciation of them – each one painstakingly rebuilt using 18th century paintings of the city by the Venetian artist Bernardo Bellotto as a blueprint. That this reconstruction was carried out during a period when Stalinist architecture dominated in the Soviet bloc makes it doubly remarkable. The rebuilding of Warsaw itself could, in the coming years, serve as a blueprint of another kind – as a route-map for the reconstruction of Ukrainian towns and cities after months of Russian aerial bombardment. While much of Europe experienced destruction on a monumental scale during World War II, the fate of the Polish capital was uniquely cruel. Most of the city was razed to the ground in retribution for the failed Warsaw Uprising of August-September 1944, when the Polish resistance attempted to liberate the city from Nazi occupation. Despite being poorly equipped, the Poles succeeded in killing or wounding several thousand German fighters in a battle lasting for two months, but at a terrible cost. Up to 200,000 Polish civilians were killed, mostly in mass executions, and once the Germans had quelled the uprising, they systematically destroyed what remained of the city, reducing more than 85% of its historic old town to ruins. Today we can only imagine how daunting the task of reconstruction must have seemed. Indeed, some suggested at the time that what remained of Warsaw should be left as a memorial and the capital relocated elsewhere. Many residents and refugees, who returned once Soviet and Allied forces reoccupied the ruined city, were formed into work brigades tasked with clearing the vast amounts of debris, as were German prisoners of war. It was estimated that the sheer volume of rubble – around 22 million cubic metres of the stuff covering almost the entire city – meant that it would take 20 years to transport it out of the city by daily goods trains. Amid the post-war scarcity, Poland lacked the financial resources to purchase construction materials. And the hundreds of brickworks that had flourished in Warsaw before the war – many of them owned by Jews – no longer existed. If the city was to rise from the ashes, the only option was to reuse the rubble from former buildings to rebuild anew, and a host of new construction techniques were invented to fashion new building materials from old. The Polish word Zgruzowstanie came into use to refer to this post-war innovation in recycling building materials. It was also the name of a recent exhibition at the Museum of Warsaw about the city’s reconstruction, translated into English as Rising from Rubble. The exhibition was curated by architectural historian Adam Przywara, based on his PhD research about the new technological developments that emerged during Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. The most important of these was gruzobeton, or rubble-concrete – a mix of crushed rubble, concrete and water, which was formed into breeze-blocks and became one of the main symbols of post-war Warsaw. Innovative methods were used to reconstitute old bricks and use them in new buildings. Rubble from the former ghetto was formed into building materials and used to build new neighbourhoods. Salvaged architectural details from demolished buildings in the old town were added to the reconstructed facades. Iron was recovered and reused. Mass demolitions even took place in other Polish cities, including Wrocław and Szczecin, to provide more bricks to rebuild Warsaw. Rubble that could not be used in construction was piled up in huge mounds to form geographical features including the Warsaw Uprising Mound, Moczydłowska hill and Szczęśliwicka hill. Although the old town was – remarkably – largely rebuilt by 1955, reconstruction elsewhere in the city lasted until the 1980s, and rubble became a national symbol used by the communist regime to represent the collective effort of reconstruction and a brighter, socialist future. The Rising from Rubble exhibition is more than just a lesson in history. “There are two areas of contemporary relevance: the idea of sustainable architecture, and how it might relate to rebuilding in Ukraine,” Przywara is quoted in The Guardian. Today Warsaw is home to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees and is a key transit point for travel to and from Ukraine. Numerous Ukrainian and European delegations, architects and city planners have passed through and made a point of visiting the exhibition, taking Przywara’s point that the city’s post-war reconstruction could become a blueprint for rebuilding Ukraine’s urban landscapes. The mayor of Mariupol was one such visitor, and the parallels between last year’s Russian air strikes on Mariupol and the bombing of Warsaw nearly 80 years earlier are plain for all to see.

0 Comments

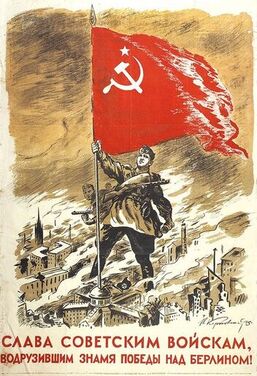

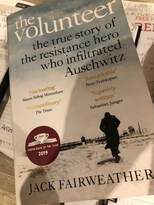

Eighty years ago, the biggest Jewish revolt against Nazi aggression was under way. The Warsaw ghetto uprising, which lasted from 19 April-16 May 1943, was an attempt to prevent the deportation of the remaining population of the ghetto to the gas chambers. The previous summer, more than a quarter of a million Jews had been transported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Foreseeing their own fate, the remaining residents developed resistance movements, smuggled weapons into the ghetto and prepared to fight. They knew that victory was impossible; they fought instead for the honour of the Jewish people, and to prevent the Germans from choosing the time and place of their deaths. On 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover, Germans entering the ghetto to begin the deportation were met by gunfire, grenades and Molotov cocktails. Pitched battles raged for days, until the Germans resorted to burning down the ghetto, block by block. Thousands of Jews took refuge in sewers and bunkers, which the Nazis then destroyed. The uprising came to an end on 16 May 1943. Around 13,000 Jews had died, and a further 55,000 were captured and taken to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek. The presidents of Germany, Poland and Israel gathered on 19 April at a memorial on the site of the former ghetto to mark the 80th anniversary of the uprising. “I stand before you today and ask for forgiveness,” German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier said. “The appalling crimes that Germans committed here fill me with deep shame… You in Poland, you in Israel, you know from your history that freedom and independence must be fought for and defended, but we Germans have also learned the lessons of our history. ‘Never again’ means that there must be no criminal war of aggression like Russia’s against Ukraine in Europe.” A 96-year-old Polish Holocaust survivor, Marian Turski, warned against apathy in the face of rising hatred and violence. “Can I be indifferent, can I remain silent, when today the Russian army is attacking our neighbour and seizing its land?” he questioned. The anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising comes as Russia is preparing to commemorate its own wartime anniversary – that of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. The Kremlin continues to draw parallels between the Second World War and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that Russia is fighting Nazis and battling for its survival against an aggressive force from the West that his hellbent on its annihilation. Russia’s motivation for its war in Ukraine is to ensure that “there is no place in the world for butchers, murderers and Nazis,” Putin said last year. “Victory will be ours, like in 1945.” But Victory Day, celebrated in lavish style on 9 May every year in Russia, will entail less pomp and ceremony than usual. Several cities are scaling back their celebrations for security reasons, fearing attacks by pro-Ukrainian forces following a spate of explosions and fires in recent days involving Russian energy, logistics and military facilities. The reduced scale of events also signals a degree of nervousness that the parades could become an outlet for disaffection with the war in Ukraine. Most notably, Immortal Regiment processions, which take place in all major towns and cities across Russia, have been cancelled this year. During the parades, hundreds of thousands of people march carrying photographs of relatives who fought or died during World War II. Putin himself attended an Immortal Regiment march in Moscow last year, holding a portrait of his father. The procession is a key event in the glorification of Russian sacrifice in the defeat of Nazi Germany – a cornerstone of Russia’s nationalist resurgence during Putin’s two decades in power. Ostensibly called off because of fears of a terrorist attack, Immortal Regiment processions risk highlighting the human cost of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The Kremlin fears that thousands of Russians would march with photographs of family members killed in the current war, bringing into sharp focus Russia’s mounting losses, and potentially risking the morphing of processions into protest events. The Russian authorities remain tight-lipped about the scale of the country’s losses in Ukraine. The most recent update came back in September, when the military reported that nearly 6,000 Russian soldiers had lost their lives. The US estimates Russian casualties in Ukraine to amount to over 200,000 dead or wounded. During last year’s Victory Day celebrations, 125 people were detained for protesting about the war, many of them at Immortal Regiment parades.  Most Jews in North America and much of Europe can trace their roots back to the Russian Empire, once home to the world’s largest Jewish population. But how many of us actually understand how our families ended up there in the first place? The basics are fairly well known. After the Roman sacking of Jerusalem in 70AD, Jews scattered across the Roman Empire, which covered most of southern and western Europe and north Africa. By the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, the Jewish diaspora had spread right across Europe. The split into two distinct communities: the Sephardi on the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazi along the Rhine in Germany occurred around the 10th century. During the Crusades in the 13th-15th centuries, Jews were expelled from much of western Europe, including from England in 1291, France in 1343 and much of western Germany in the early 15th century. Many fled east, to the one country that offered a safe haven for Jews – Poland. Here King Casimir the Great (reigned 1333-1370) welcomed Jews for their trades and skills and protected them as “People of the King”. But by the 18th century, Poland was a weak and failing state, preyed on by its more powerful neighbours: Prussia, Austria and Russia. These three great European powers divided the country up between them in the three Partitions of Poland of 1772, 1793 and 1795. The area to the southwest of Kiev where my family came from became part of the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great in the second partition of 1793. Since 1991 it has been in independent Ukraine. Bert Shanas, a retired journalist turned genealogist from New York, has traced his family history to shtetls southwest of Kiev from at least the mid-1600s, and it is from his research that I have borrowed the contents and title of this article. The typical Ashkenazi Jew from this region, Shanas says, has an ancestral line that began in Africa, migrated to the Middle East, and from there into Europe, through France, to present-day Germany and into Poland, to an area that went on to become Russia then Ukraine over the course of some 200,000 years. Using a combination of DNA testing, recent scientific studies, archaeological discoveries, and biblical and historical scholarship, Shanas has traced the likely route his ancestors would have taken. His male family line would have had its origins in east Africa 60,000-70,000 years ago – around present-day Ethiopia, Kenya or Tanzania. Major climatic changes would probably have forced his ancestor to journey to the northeast in search of an adequate food supply, most likely travelling in a group of around 200 people. They would have crossed the Red Sea – then a smaller, shallower channel – into present-day Saudi Arabia and continued eastwards along the coast of the Arabian Sea until they reached the Indus Valley, the area that is today Pakistan. Thousands of years later, it is likely his ancestors would have broken off from the group and headed north through Iran to settle in what is now Turkey, around 40,000 years ago. About 10,000-15,000 years ago, they would have moved on to the Middle East, where Jewish history began – with Abraham, who came from the city of Ur in Babylonia, now southern Iraq - around 3,200 years ago. Shanas believes that following the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, his ancestors would probably have travelled from the Middle East through Turkey, Greece and Italy, then north through France around the year 1400 and from there to Germany. Around 1500, they would have moved east again, into Poland and by 1600-1700 were settled in the area near Kiev. DNA analysis indicates that Shanas’ female family line probably ended up in Poland by a different route, trekking north from the area around present-day Kenya or Ethiopia around 60,000 years ago, through Sudan and Egypt into the Middle East. They would have survived the last Ice Age somewhere around Mediterranean Europe and once the glaciers retreated, spread throughout Europe between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago. His ancestral line would probably have migrated to the Caucasus mountains then arced over the Black Sea into the Balkans. From there the DNA trail branches in two directions, the first heading north into Finland, passing through Poland on the way, and the second going west along the Mediterranean through France and Spain, into Portugal. DNA analysis shows that his genetic female ancestors were not grouped in great numbers in any one spot, but were scattered across eastern and western Europe, and their exact route to Ukraine is unclear. A study of the origins of Ashkenazi women by Professor Martin Richards at the University of Huddersfield in the UK and cited by Shanas in his research, found that in at least 80% of the cases studied, the DNA of Jewish women traced back to Europe – unlike that of men, which traced back to the Middle East. Richards concluded that the vast majority of Jewish men who fled the Middle East for Europe after the Roman conquest did not take women with them. Instead, they married local European women, who then converted to Judaism. With grateful thanks to Bert Shanas for allowing me to use his research for this article.  Moving forward in time from my last article, which showcased a short film set in the Pale of Settlement in the mid-19th century, this one is about a full-length feature where the action takes place on the Polish/Ukrainian border during World War II. My Name is Sara is the story of a 13-year-old Polish Jew who flees from the Nazis to a small rural settlement and finds refuge – although a cold and insecure one - with a Ukrainian farming family. The film is an American/Polish co-production directed by Steven Oritt. It was filmed on location in Podlasie, Poland, strongly evoking a sense of the nature of the area, the sweeping, rural landscapes, the forests and country towns as they would have looked in the middle of the last century. Filming locations included Tykocin, Czerlonka, Białystok and Puchły. At her parents’ insistence, Sara and her brother escape from the ghetto in Korzec, Poland, close to the Ukrainian border, before it is liquidated in 1942. They flee in the middle of the night through miles of forest, across a river where Sara would have drowned had her brother not been there to save her. They eventually make their way to the home of a Ukrainian woman whom Sara’s parents had paid to take in and care for their two oldest children. They stay for some days, but sense that the woman is nervous, and that they should move on. Sara makes the decision to continue alone. Walking on towards Ukraine, Sara creates a false identity and life story for herself, using the name of a Catholic friend. Luckily, she is well versed in Catholic prayers and rituals, knowledge that without doubt saves her life on several occasions. Determined above all else to guard the secret of her true identity, she finds work on a small farm owned by a Ukrainian couple, and soon discovers that they harbour secrets of their own. The role of Sara is powerfully played by a young actress by the name of Zuzanna Surowy. There are moments of horror and sacrifice, as one would expect from a film depicting events that took place during the Holocaust, but this is not a depressing film. It is beautifully shot, to the extent that many of the scenes look almost like paintings. The film was released in the US in 2019, and in the UK, where it was oddly renamed The Occupation, in 2020. My name is Sara is based on the true story of Sara Góralnik, who was born in Korzec on May 10 1930. She was the second of four children, the only girl, and the only one of her family to survive the Holocaust. Her hometown was occupied by the Soviet Union in 1939, then by the Nazis in 1941. When Sara was just 12 years old, her family received word that all Jews living in the ghetto were to be murdered. “You and your brother will run away,” her mother said, according to Sara’s testimony to the Shoah Foundation in 2012. “And, I said ‘No. If they are going to kill you, let them kill me. I’m not going.’” Sarah’s son Mickey Shapiro, who was born in a displaced persons’ camp in Germany in 1947, is one of the film’s executive producers. “I was curious and I knew bits and pieces of the story, but I didn’t get all of it and I wasn’t going to push her to tell the story,” says Mickey. “My mother never talked about it. She never really verbalised what happened.” Sara began to talk a little more as she got older, then after a visit to the US Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington DC with her grandchildren, she began to share her story in detail. “This is a strong movie about a strong woman who survives. It needs to be seen,” Mickey says. Sara died in 2018.  I finally had the opportunity during lockdown to watch a documentary that I’d been wanting to see for a long time. My Dear Children, a 2018 film by director and co-producer LeeAnn Dance, tells the personal and heart-rending tale of a family separated by thousands of miles as a result of pogroms during the Russian Civil War. Central to the story is Feiga Shamis, a mother who strives to protect her 12 children from the turbulence and violence around them. The pogroms of 1917-1921 were far more terrible than any of the anti-Semitic violence that had gone before, with a death toll estimated anywhere between 50,000 and 250,000, and up to 1.6 million injured, attacked, raped, robbed, or made homeless in the largest outbreak of anti-Jewish violence before the Holocaust. The number of individual pogroms is estimated at more than 1,200. Feiga’s 16-year-old son was killed during one of these, while her husband – like my own great-grandfather – died during the typhoid epidemic of 1918-19. “We overheard them saying they should kill all the Jewish children so the Jews would die out,” Feiga wrote. It was time to plot her escape. With her older children married off or sent to the US, she fled to Warsaw with the four youngest, where she placed two of her children – eight-year-old Mannie and 10-year-old Rose – in an orphanage, a fairly common practice at the time. “I thought the children would be safer in the orphanage,” she wrote, “so I took them there.” From Warsaw, the two children were selected as part of a rescue effort by Isaac Ochberg, a Jewish South African philanthropist, who managed to bring to safety nearly 200 Jewish orphans from his former homeland. At great personal risk, he travelled around Eastern Europe collecting children from orphanages and bringing them to Warsaw—to the orphanage where Feiga had placed her children. Only later did Ochberg learn the children’s mother was alive. When Feiga learned of the plan, she faced a heartbreaking decision—keep the children with her, or let them go, to a place half a world away where she would probably never see them again, but where she was assured that they faced a better future. She chose to let them go. My Dear Children is based on a long letter that Feiga wrote to Rose and Mannie after she had emigrated to Palestine in 1937 to live with one of her older daughters. She gave it to Mannie on the one occasion they met after his and Rose’s departure for South Africa. As a young soldier in the South African army, Mannie was posted to Egypt, from where he took a week’s leave to visit his mother. Tragically Mannie cut short his week-long visit to just a single day, with he and his mother unable to connect to one another. Mannie never read his mother’s letter, suppressing a past that was too painful to contemplate. For the rest of his life, Mannie would agonise over why his mother had sent him away, and neither he nor his sister Rose would ever talk about their childhood back in Russia. It wasn’t until after Mannie’s death that his widow had the letter translated from Yiddish into English, printed as a small book, and distributed among members of the family. The scenes that Feiga witnessed during the Civil War and her experiences during that time resonate deeply with the recollections of my grandmother, documented in my book A Forgotten Land. In particular, Feiga wrote about becoming a black-market vodka trader, bartering vodka for food to keep her family alive. My grandmother too was a black-market trader at this time, dealing in food, and later gold, as the sole breadwinner for her grandparents, siblings and cousins. It is clear from her writing that Feiga remained racked with guilt and suffering over her decision to allow her children to leave for South Africa, and she wrote the letter as a justification and explanation for what she had done. In 2016, Mannie’s daughter Judy and granddaughter Tess set out on a trip to Poland and what is now Ukraine, hoping to find answers as to why Mannie refused to talk about his past and what drove Feiga to the choice she made. They found a landscape virtually erased of its Jewish past. “The Holocaust did not happen in a vacuum. The pogroms of 1917-1921 should be seen as a precursor to the greater tragedy just 20 years later. My Dear Children shows the consequences of unchecked, or worse – officially sanctioned – anti-Semitism, and given the increasing incidents of anti-Semitism today, this story remains relevant today. Feiga’s story is not unique. Nearly 80% of the world’s Jewry can trace their roots to Eastern Europe, thus Jews around the world share Feiga’s story. Many likely have no idea they do so.” LeeAnn Dance said in an interview for the Washington Jewish Film Festival in 2018. For more information about My Dear Children, click here www.mydearchildrendoc.com  Books have provided me, like many others, with a place to escape during this strange Covid era. Perhaps paradoxically, my escape has not been to happier times, but to the bleakest, most terrible period of mid-20th century history, which has absorbed me during recent months. Bringing myself back again and again to the Holocaust has helped me appreciate all the freedoms we have still been able to enjoy this year, as opposed to those that the coronavirus has taken away. The Librarian of Auschwitz by Antonio Iturbe (translated from the Spanish) tells the fascinating story of Dita Kraus, who was 13 in 1942 when she was deported from her home in Prague to Terezin (Theresienstadt), and later to Auschwitz. Dita – a feisty, strong-minded teenager – and her parents were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, a showcase area established in September 1943 most likely in case a delegation of the International Red Cross were to come to inspect conditions there. The Nazis wanted to preserve the illusion that children could live in Auschwitz, and to contradict reports that it was a death camp. In the event, though, the International Red Cross inspected Theresienstadt but chose not to come to Auschwitz after all, in the mistaken understanding that Theresienstadt was the Nazi’s final destination for Czech Jews. Perhaps if the visit had taken place, just perhaps, it would have created such a public outcry that the allies would have been forced to take action. But once the threat of a Red Cross visit disappeared, the family camp had no further purpose and was liquidated in July 1944. Of the 17,500 Jews deported to the family camp, only 1,294 survived the war. Prisoners at the family camp were not subjected to selection on arrival and were granted several other privileges. Rations were a little better, heads were not shaved and civilian clothes were permitted. Family members were able to stay together; males and females were assigned to separate barracks, but were still able to meet one another outside their quarters. Prisoners were given postcards to send to relatives in an attempt to mislead the outside world about the Final Solution. Strict censorship, of course, prevented them from telling the truth. Prisoners in the family camp had “SB6” added to the number tattooed on their arm, indicating that they were to receive “special treatment” for six months. When the six months were up, each transport was liquidated and a new one took its place. In spite of the privileges and so-called special treatment, living conditions were still abysmal by any standards other than those of a concentration camp, and the mortality rate was high. Dita’s father died of pneumonia in the camp. The family camp was home to a clandestine school, established by Fredy Hirsch – a German Jew and former youth sports instructor – who persuaded the authorities to allow block 31 to act as a special area for the camp’s 700 children. Inside the block, the wooden walls were covered in drawings, including Eskimos and the Seven Dwarves, stage sets for plays performed by the children. Stools and benches took the place of rows of triple bunks. Education was officially forbidden, with the children permitted only to learn German and play games. But that did not prevent Hirsch and his teachers from organising lessons on all manner of subjects, including Judaism. There were no pens or pencils, of course, and the teachers would draw imaginary letters or diagrams in the air rather than on a blackboard. And inside block 31 was something else, something “that’s absolutely forbidden in Auschwitz. These items, so dangerous that their mere possession is a death sentence, cannot be fired, nor do they have a sharp point, a blade or a heavy end. These items, which the relentless guards of the Reich fear so much are nothing more than books: old, unbound, with missing pages, and in tatters. The Nazis ban them, hunt them down.” Dita became the custodian of block 31’s motley collection of books, which had been secretly taken from the ramp where the luggage of incoming transports was sorted. There were eight books – eight small miracles – which included an atlas, a geometry book, a Russian grammar, A Short History of the World by H G Wells, a book on psychoanalytic therapy, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas and a Czech novel: The Adventures of the Good Soldier Svejk, as well as a Russian novel with no cover. The school also had six “living books”, stories learnt by heart and recounted by the teachers. Dita cared for her eight books like she would her own children, caressing them, putting their pages back in order, gluing their spines and trying to keep them neat and tidy. She took huge risks on their behalf, removing the books from their hiding place each day and lending them out to teachers as requested, always alert to the possibility of an unplanned inspection or visit from the SS. Despite the many books I’ve read about the death camps, and a visit to Auschwitz in 2018, literature on the subject still has the power to shock. In this book, for me, it was this passage, in which a woman, together with her young son, is told that they will be transferred from Birkenau to be with her husband – a political prisoner – in Auschwitz, three miles away: “Miriam and Yakub Edelstein have sharp minds. They immediately understand why they have been reunited. No-one can begin to imagine what must pass through their minds in this instant. “An SS corporal takes out his gun, points it at little Arieh, and shoots him on the spot. Then he shoots Miriam. By the time he shoots Yakub, he is surely already dead inside.” This is a beautifully written story about a time and place that was hideous and brutal. As the author says, “The bricks used to construct this story are facts, and they are held together in these pages with a mortar of fiction.” I urge you to read it for yourself.  During lockdown, I have found my reading dominated by the Second World War, and have been struck by some parallels between that era and this strange period that we are living through now. The second of the wartime books to feature in my blog is The Volunteer by Jack Fairweather, which has the subtitle “The true story of the resistance hero who infiltrated Auschwitz”. I read it straight after finishing Bart van Es’ fascinating tale The Cut Out Girl about a young Dutch girl whose parents sent her away shortly before being deported to Auschwitz. The Volunteer picks up on their experience. The book charts the true story of Witold Pilecki, a member of the Polish resistance who agrees to get himself sent to Auschwitz in September 1940 in order to build a rebel army within the concentration camp and lead an uprising against its Nazi oppressors. Witold succeeds in developing an extensive network of resistance in Auschwitz, but he knows that ultimately a camp rebellion will be impossible without external support. His intention – through numerous oral, written and transmitted reports that he miraculously manages to smuggle out of the camp from October 1940 onwards at tremendous risk to all involved – is to get news of the camp to the Allied leadership. Each report makes the same request: that the Allies make bombing raids over Poland to sever the train lines bringing new transits of prisoners, and to destroy Auschwitz and thereby assist the prisoners with an uprising from within. Witold argued that although the bombing would kill hundreds, it would save the lives of many thousands more over the course of the war. While the author describes some of the unimaginable horrors of Auschwitz, it feels sometimes that these no longer have the power to shock, so familiar are we today with the narrative of the Holocaust. Yet Witold’s reports smuggled out of the camp exposed to the outside world the events that are now so familiar. Just imagine being confronted with the atrocities of Auschwitz for the first time. Gas chambers. Daily transports of Jews being divided between those to be murdered immediately, and those to die a longer, slower death by starvation, hard labour and disease. Emaciated bodies. Random shootings and other acts of extreme violence. Obscene medical experiments. It is hardly surprising that some dismissed reports of the mass killings as fiction, they must have read like the script of a horror movie. But the Polish resistance in Warsaw took Witold’s reports seriously and used a network of underground couriers to bring news of atrocities committed at Auschwitz to the notice of the Polish government in exile in London and its leader Wladyslaw Sikorski. The experience of the couriers who carry his reports – transmitted verbally to Warsaw, then written up, microfilmed and sent to London – is an adventure story in its own right, fraught with danger at every turn. One courier, a Polish underground agent by the name of Napoleon Segieda, carried a microfilm with news of the first mass gassings of Jews in May 1942 in a false-bottomed suitcase from Poland via Austria, Switzerland, France, Spain, Gibraltar and Scotland finally reached London six months later. He called the delay “heartbreaking”. The Nazis had killed nearly a quarter of a million Jews in Auschwitz in that time. Sikorski repeatedly attempted to engage the British government to pay attention to the horrors committed in Nazi concentration camps in Poland and, from 1942, the mass murder of European Jews. I was deeply shocked to learn how much the Allied leaders knew of what was happening in Nazi-occupied Europe that they kept from the media and from the public, and refused to act on. Churchill and Roosevelt were both briefed repeatedly about the events taking place in Poland, but failed to comprehend the true nature of Auschwitz and its central role in Hitler’s plans. And from late 1942 reports emerged from other sources that backed up the smuggled information from inside Auschwitz. The Allied leadership knew what was happening, and yet they did nothing. Churchill over and again dismissed out of hand the idea of bombing the camp and its train lines, finding numerous excuses for inaction – he didn’t want to upset the local population with too many grim images, feared stirring up violent anti-Semitism at home, and was wary of reprisals against captured British airmen. Most damningly, he and Roosevelt believed bombing Auschwitz would a distraction from the overall war effort. Indeed, in early 1943, the US State Department even instructed its legation in neutral Switzerland to stop sending information from Jewish groups about the situation in Europe as they might inflame the public. Witold and his comrades continued to conduct their activities in Auschwitz – at huge personal risk and contending with sickness, hunger and deprivation – always with the expectation of support from the Allies that never materialised. Witold could not understand the lack of action, and wondered whether his reports were being intercepted and failing to get through to the Allies. He knew that a major uprising within the camp was destined to failure without help from outside, and several unsuccessful attempts to start a camp rebellion confirmed this belief. During Witold’s time in Auschwitz, many of his co-conspirators were discovered and killed. Having finally learnt that his reports from the camp had indeed reached the Polish resistance in Warsaw and travelled from there to London, but that international focus was elsewhere and few paid much attention to Auschwitz, Witold lost heart and began to plot his own departure from the camp. Miraculously, he and a colleague managed to escape in April 1943, but his work was not done. Witold continued his attempts to rally support among the Polish resistance for an attack on Auschwitz. But to his bafflement, his entreaties continued to fall on deaf ears. Few people in Poland were talking about the camp’s role in the murder of Jews, and meanwhile gangs of blackmailers roamed the streets in search of any Jews still in hiding. From outside the camp, Witold continued to write reports and to work for the Polish underground in spite of his increasing frustration. He survived the war and worked on his memoirs, but his story of futile heroism was forgotten. He was arrested by the Soviet authorities in May 1947 and sentenced to death at a show trial a year later. Had the outside world heeded Witold’s calls, millions of lives could have been saved. Churchill’s unwillingness to step in to help the Jews, Poles, gypsies, homosexuals, communists – all those deemed inferior by the Nazi ideology – brings me back to the current move to reassess many historical figures that have long been celebrated as national heroes. The recent wave of Black Lives Matter protests resulted in the toppling of statues of those who benefitted from the slave trade and colonialism. The statue of Churchill in London’s Parliament Square was vandalised then boarded up to prevent further damage by anti-racism protestors. Posterity has for too long airbrushed out the uncomfortable bits of history – the racism and bigotry that most of us today can no longer accept. That the tragic death of George Floyd spawned a worldwide movement to highlight inequality and bring institutional racism to the very top of national agendas is testament to how far we have come in 75 years. But it also highlights just how far we still have to go before all lives are considered equal irrespective of colour, creed, nationality or sexual orientation.  I have just come across a fascinating document published last year by Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter – a private multinational initiative aimed at strengthening mutual comprehension and solidarity between Ukrainians and Jews – tracing the origins of Jews in Ukraine from antiquity to the 20th century. A Journey through the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter is based on an exhibition that toured Canada in 2015 and documents how the stories of these two often antagonistic peoples are intertwined and incomplete without one other. Ukraine itself is a thoroughly modern concept. Prior to independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, the country had only experienced two very brief and chaotic wartime glimpses of independence – first in 1918 and again in 1941. The territory of modern-day Ukraine has for many centuries been the home of diverse peoples, including one of the oldest and most populous Jewish communities in the world. This blog post is a brief and very distilled version of the first part of the Journey and I will continue the story in my next post. I thoroughly recommend following the link at the bottom of this page to read the full document. As well as fascinating historical information, it contains some wonderful photographs and illustrations. The Jewish presence on Ukrainian lands dates all the way back to antiquity. Jews first came to the area as merchants more than 2,000 years ago and began to settle in the coastal towns of Crimea. These Jews became known as Krymchaks. They were later joined by a Jewish sect known as the Karaites that preserved its ancient Biblical faith while rejecting the Talmud and embracing the practices and the Turkic language of the local population. Some centuries later, during the early medieval period, travelling Jewish traders and merchants settled in the territory that became Transcarpathia (later in Hungary before becoming part of Ukraine). And around the 9th century Jews fleeing persecution in the Byzantine Empire found safe haven in the Khazar Khaganate, which encompassed Kiev and much of the area to the south and east, where they were accepted as citizens. The Khazar Khaganate came to an end in the 960s with the creation of Kyivan Rus' (960–1240), a conglomerate of principalities in central Ukraine that united several Slavic and other groups. In 988 Prince Volodymyr adopted the Byzantine Greek form of Christianity as the official religion of Kyivan Rus', and Eastern Orthodoxy has remained the dominant religion in Ukrainian lands ever since. Although Church writings in Kyivan Rus' included anti-Judaic themes, the Kyivan princes welcomed the role Jews played in trade and finance, and from the late eleventh century Kyivan Rus' became a refuge for Western European Jews fleeing persecution by the Crusaders. After unifying the southwestern areas of Kyivan Rus', Prince Danylo of Galicia-Volhynia invited Armenians, Germans, Jews, and Poles to settle in the area, bringing with them artisanal and commercial skills. Interestingly, my grandmother talked about an Armenian quarter in the shtetl of Pavolitch, where she grew up. Although some miles east of Galicia-Volhynia, its origins may have dated from this era. In the 13th and 14th centuries small Jewish communities developed in Galicia-Volhynia, and Jews helped establish Lviv as a centre for international trade between Central Europe and lands to the east. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania later assumed control over these regions, affording Jews royal protection, but not granting them the rights of citizens. Jews were subject to a raft of economic measures restricting them to work in jobs such as currency exchange and moneylending, breeding the stereotype of the miserly Jewish moneylender. Jews tended to reside in, and help develop, urban areas, making towns such as Lutsk important centres of Jewish life. Around the same time, Polish princes offered protection to Jews, welcoming them to settle in Poland. This encouraged significant numbers of Jews fleeing persecution in Western Europe to migrate to Poland. In 1507 the Grand Duke of Lithuania and King of Poland granted the Jews a charter of protection that exempted them from the jurisdiction of municipal authorities, and offered security against physical attack and the right to practice their religion. These protections prompted Yiddish-speaking Jews from Central Europe to migrate eastward in significant numbers, living among local Christian Ukrainians and other ethnic groups. Small communities of these Ashkenazi Jews could be found in several northern Ukrainian towns, in contrast to the earlier Jewish inhabitants there, whose primary language was probably Slavic. Further east, the Crimean Khanate covered much of present-day central and eastern Ukraine from the 15th to 18th centuries. As elsewhere in the medieval Muslim world, Jews in the Crimean Khanate were considered a tolerated monotheistic minority and were allowed to engage in commerce and freely practise their religion, as long as they accepted a subordinate status and kept a low profile. The largest migration of Jews eastward into Ukrainian lands came as a result of Poland’s territorial expansion and colonising efforts following the Union of Lublin in 1569, which united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and created the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (1569–1795). In the Commonwealth, Polish nobles established around 200 private towns around their estates, which attracted considerable numbers of Jews. Jews often administered the nobles’ estates, managing the land, mills, taverns, distilleries, and wine-making operations. They also collected taxes for the Polish nobles and provided credit to both the landlords and peasants. Jewish merchants and artisans, driven out of several Polish cities by their economic competitors, also settled in these towns where they established regular markets and fairs. Jews often found themselves caught between the nobility, who expected them to maximise profit, and the peasants, who resented the economic burdens imposed on them. Between 1569 and 1648 the number of Jews in the provinces of Volhynia, Podolia, Kyiv, and Bratslav increased from 4,000 to 52,000, encompassing 115 localities. Jews in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth gained significant autonomy with Jewish regional councils and a central body of Jewish self-government. Each Jewish community (kehilah) had its own kahal, or administration, run by leading members of the Jewish and Rabbinical community. Each kahal sent representatives to meetings of a national Jewish council, the Va’ad (or Sejm in Polish) which represented the Jews of the Commonwealth before the king and the Polish parliament. The council also debated and legislated major religious and socio-cultural issues, organised responses to attacks on Jews, served as a high court of appeal for Jewish community courts and apportioned among the communities liability for the collective tax on Jews. It was in the small market towns owned by the nobility of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth that Jews created the shtetl culture mythologised in Jewish folklore. Shtetl is a Yiddish word of Germanic origin meaning ‘small town’ and commonly refers to a small market town with a large Yiddish-speaking Jewish population, which existed in Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. It is distinct from a dorf (village) and from a shtot (large town, city). A shtetl would generally have between 1,000 and 15,000 Jewish inhabitants, comprising at least 40 percent of the town’s population. The shtetl was home to all classes of Jewish society, from wealthy entrepreneurs to petty shopkeepers, innkeepers, shoemakers, tailors, water carriers, and beggars. Cultural life was regulated by the Jewish religious calendar and traditional customs, characterised by attitudes, habits of thought, and a unique rhetorical style of speech full of allusions rooted in Talmudic lore. Despite widespread poverty and episodes of anti-Semitic violence, the shtetl produced a vibrant folk culture and a remarkably expressive language, Yiddish. The Polish lands where so many Jews had settled became part of the Russian Empire during the partitions of Poland under Catherine the Great in 1772–95. Since the late fifteenth century, Jews had been forbidden to settle in Russia, but with the annexation of Polish territories, Catherine became the ruler of the largest Jewish population in the world. Influenced by Enlightenment thinkers and hoping to benefit economically from Jewish trade, Catherine resisted pressure from the Orthodox Church to expel the Jews and settled on a compromise. She created the Pale of Settlement. Jews were barred from Russian cities and restricted to living in the formerly Polish lands, territory that falls within present-day Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania. Some assimilated Jews received special permission to live in the major imperial cities (including Kyiv), others took up residence in the cities illegally. The Pale lasted until the fall of the Russian Empire in 1917. Click here to see the document on which this article is based ttps://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/media/UJE_book_Single_08_2019_Eng.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2D2QAuBtjsIqF1kHi4eRUlxBZT-UFPR3usj0741Cp3nnnouJT1icJGphM  I recently read a fascinating obituary of the last musician to grow up playing traditional Jewish music in Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. Leopold Kozlowski died in March at the ripe old age of 100. Kozlowski gained fame as the “Last Klezmer of Galicia”. He was an expert on Jewish music, having taught generations of klezmer musicians and Yiddish singers in Poland. He continued to perform until shortly before he died. He was born Pesach Kleinman in 1918 in the town of Przemyslany, near Lviv, which was then in Poland and is now part of Ukraine. His grandfather was a legendary Klezmer player by the name of Pesach Brandwein, one of the most famous traditional Jewish musicians of the 19th century. With his nine sons he performed at Hassidic celebrations and even for heads of state, including the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph. Brandwein created a musical dynasty, with many of his descendants forming family orchestras throughout Galicia. The clan also gained renown in America. Brandwein’s son, the clarinetist Naftuli Brandwein, settled in New York in 1908 and became known as the “King of Jewish Music.” Because of the family’s reputation, Brandwein’s youngest son, Tsvi-Hirsch, decided that in order to prove himself, he should change his name and go it alone. He adopted his mother’s maiden name, Kleinman, to avoid association with his famed grandfather and uncle. His son Pesach — later to be known as Leopold Kozlowski — and his brother Yitzhak would prove to be the greatest musical talents of all Brandwein’s grandchildren. Kozlowski played the accordion and later the piano, while his brother played the violin. By the 1930s, as teenagers, they began playing alongside with their father, but times were hard and most families could no longer afford to hire a band for weddings. The boys devoted nearly all of their free time to practicing and performing and were later admitted to Conservatory in Lviv, completing their studies in 1941. By this time their home town had become part of Soviet Ukraine and was flooded with Polish Jews who gave increasingly dire accounts of the situation in Nazi-occupied Poland. When Germany invaded the USSR on June 22, most believed that the Germans would only kill Jewish men of fighting age. Kozlowski’s mother told him, his brother and his father to flee. The three men travelled 200 miles on foot in a little over a week, their instruments slung over their shoulders. But they were intercepted by the German army on the outskirts of Kiev. Realising that capture meant near certain death, they searched for a place to hide, settling on a cemetery where they dug up the earth with their hands and hid in coffins alongside the dead. Finally emerging from hiding, they were immediately captured by the German army. But just as the soldiers were about to fire, Kleinman pleaded with them to allow him and his sons to play a tune. The soldiers listened, and slowly they lowered their rifles. After checking to see that no-one was watching, they gave Kleinman and his sons some food and left. The three men returned to their coffins. Unable to remain among the dead any longer, and with no other option open to them, they eventually headed home, travelling by night and hiding in the forest by day. Three times German soldiers captured them, and each time they were released after playing a song. Back in Przemyslany, the Gestapo ordered all Jews over 18 to assemble in the marketplace. From there the Germans led 360 Jews into the forest where they were forced to dig their own graves and then shot. Among them was Kleinman, while his wife was murdered soon afterwards when German soldiers found her hiding in a nearby barn. Kozlowski and his brother attempted to flee, but were quickly captured and sent to the Kurovychi concentration camp near Lviv. Both brothers soon joined the camp’s orchestra and when SS officers learned of Kozlowski’s skill as a composer, they ordered him to compose a “Death Tango” to be played by the orchestra every time Jews were led to their execution. The officers would bring the brothers to their late-night drinking sessions and command them to play. They were frequently made to strip naked and the Germans extinguished cigarettes on their bare skin. Eventually the two men joined a group that planned to escape. They befriended a Ukrainian guard with a drinking problem, and while the brothers distracted a group of SS officers with their music, a third prisoner stole a bottle of vodka from them and gave it to the guard while he watched over the camp fence. Once the guard passed out, the inmates grabbed his wire cutters and made a hole in the barbed wire. Immediately the camp’s searchlights fired up and gunfire reverberated. Several inmates were mown down by bullets just outside of the fence; others were caught by guard dogs and executed. Running alongside his brother with his accordion over his shoulder, Kozlowski felt several sharp jabs in his shoulder. When he examined his accordion later, he found multiple holes; the accordion had blocked the bullets’ path, leaving him unscathed. The accordion is now on display at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow. Following their daring escape, the brothers joined a Jewish partisan unit and later a Jewish platoon of the Home Army. In 1944 Kozlowski’s brother was stabbed to death having stayed behind from a mission to guard injured comrades, and Kozlowski never forgave himself for being unable to save him. Throughout the horrors of their wartime experiences, the brothers had continued to play music. Music not only saved Kozlowski’s life several times, but also helped heal his psychological wounds, his long-time friend, the American klezmer artist Yale Strom, said in an interview. After the war Kozlowski settled in Krakow and enlisted in the army. Still fearful of anti-Semitic violence, especially after the massacre of Jews in Kielce in July 1946, he exchanged his Jewish surname for the Polish Kozlowski. He served in the military for 22 years, achieving the rank of colonel and conducting the army orchestra. In 1968 he once again fell victim to anti-Semitism when he was discharged under President Wladyslaw Gomulka’s anti-Semitic campaign. “He thought to himself: ‘I’ve already changed my name, already hidden my identity and I’ve served more than 20 years in the Polish army and yet I’m still considered ‘the Jew,’” Strom said. “‘I’d be better off not hiding anymore. I might as well play Jewish music.’” At a time when most of Poland’s remaining Jews fled the country, he joined the Polish State Yiddish Theatre and began composing original scores and coaching actors to sing with an authentic Yiddish intonation. He also played at celebrations for Krakow’s Jewish community and taught children Yiddish songs. Under perestroika as the Soviet Union began to release its iron grip, Kozlowski was able to connect with klezmer musicians abroad, and in 1985 he visited the US where he met the leaders of the nascent klezmer revival movement. Later, Stephen Spielberg met Kozlowski in Krakow while scouting locations for his film Schindler’s List. The two hit it off and Spielberg hired him both as a musical consultant for the film and to play a small speaking role. Strom released a documentary, “The Last Klezmer: Leopold Kozlowski, His Life and Music,” in 1994, transforming Kozlowski into a celebrity in Poland. In old age, Kozlowski’s fame continued to grow. As well as international festival appearances and his regular concerts at the Krakow restaurant Klezmer Hois, he gave an annual concert with his students as part of Krakow’s international Jewish cultural festival. Even at 99 he was still the star of the show, playing the piano for two hours. In his final years, Kozlowski spent much of his time in Kazimierz, Krakow’s historic Jewish quarter, which has become a tourist attraction. He often received visitors from abroad at his regular table at Klezmer Hois. Among the Jewish cemeteries, synagogues that function primarily as museums, and quasi-Jewish restaurants, Kozlowski himself became a sort of tourist attraction, the last living link to the music of pre-war Jewish life. I can only wish that I had chanced upon him when I visited Kazimierz last summer. This is an abridged version of a piece that appeared in The Forward. Click here to read the full article. https://forward.com/culture/423976/klezmer-leopold-kozlowski-holocaust-survivor-spielberg-schindlers-list/  In the wake of Yom Hashoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, I came across this wonderful and heart-warming story of a holocaust survivor who after nearly 80 years has discovered the identity of the man who saved her from the fate of 6 million other Jews. Janine Webber was born in 1932 in Lviv, which at that time was in Poland but became part of Soviet Ukraine following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939. When the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, she and her family were rounded up and forced to abandon their home and move into a room together with three other families on the outskirts of the city, ahead of the formation of the Lviv ghetto. Janine’s parents created a hiding place for her, her brother and mother, but the Nazis shot her father. Her mother then died of typhus aged 29, shortly after being forced into the ghetto. Later her brother was shot by the SS while the children and their uncle and aunt were in hiding on a farm. Other members of her extended family died of disease or were deported to Belzec concentration camp. Janine wandered the countryside in search of new hiding places and worked as a shepherdess until the Polish family she lived with learnt of her Jewish identity and sent her back to Lviv. By 1943, Janine was 11 years old. Her uncle and aunt gave her a piece of paper with the name Edek written on it, and an address. They told her to find Edek if she needed help. “I told him who I was and he said, ‘Follow me – at a distance’. He took me to a building. He put a ladder against the wall and told me to climb up. I opened the door and that’s where I found my aunt, my uncle…13 Jews. I was the only child.” The building was a convent, where Edek worked as a night watchman and his sister Floriana was Mother Superior. As the situation became more dangerous, the group dug an underground bunker beneath the building and remained hidden there for nearly a year. As the group struggled with the cramped conditions and related health problems, Janine’s aunt arranged false papers for the girl and sent her to a convent in Krakow. She later moved again to work as a Catholic live-in maid with an elderly couple until the end of the war. All 14 of the Jews that Edek had protected survived the war, but they never saw him again. All they knew of their saviour was his name. And Edek was a common Polish name. Janine moved to the UK in 1956 and lives today in north London. In the 1990s she determined to try to find Edek. She approached a BBC documentary team, which spent six months trying to track him down, but with no luck. Last year she took part in a short feature film for the UK’s National Holocaust Centre and Museum, produced by one of the centre’s trustees, Marc Cave. With help from the Polin museum in Warsaw and Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, he was able to track down Edek’s true identity. Edek’s real name was Franciszek Rzottky, a 19-year old Catholic and a member of the Polish resistance. He survived internment in a labour camp and concentration camp, but never betrayed the Jews he had rescued. Rzottky later entered the priesthood and died in 1972 at the age of 49. In 1997 he, alongside Janina and Tadeusz Lewandowski who had organised food and money for the 14 Jews, were named as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem. This year, the National Holocaust Centre will plant a white rose in Rzottky’s memory. The centre’s chief executive Phil Lyons said he hopes the small ceremony will “help transform fear and persecution of ‘otherness’ into mutual acceptance at this time of rising antisemitism and Holocaust denial”. Click here to read the full story in The Telegraph https://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/finally-found-catholic-teenager-saved-nazis/ |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed