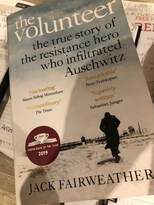

During lockdown, I have found my reading dominated by the Second World War, and have been struck by some parallels between that era and this strange period that we are living through now. The second of the wartime books to feature in my blog is The Volunteer by Jack Fairweather, which has the subtitle “The true story of the resistance hero who infiltrated Auschwitz”. I read it straight after finishing Bart van Es’ fascinating tale The Cut Out Girl about a young Dutch girl whose parents sent her away shortly before being deported to Auschwitz. The Volunteer picks up on their experience. The book charts the true story of Witold Pilecki, a member of the Polish resistance who agrees to get himself sent to Auschwitz in September 1940 in order to build a rebel army within the concentration camp and lead an uprising against its Nazi oppressors. Witold succeeds in developing an extensive network of resistance in Auschwitz, but he knows that ultimately a camp rebellion will be impossible without external support. His intention – through numerous oral, written and transmitted reports that he miraculously manages to smuggle out of the camp from October 1940 onwards at tremendous risk to all involved – is to get news of the camp to the Allied leadership. Each report makes the same request: that the Allies make bombing raids over Poland to sever the train lines bringing new transits of prisoners, and to destroy Auschwitz and thereby assist the prisoners with an uprising from within. Witold argued that although the bombing would kill hundreds, it would save the lives of many thousands more over the course of the war. While the author describes some of the unimaginable horrors of Auschwitz, it feels sometimes that these no longer have the power to shock, so familiar are we today with the narrative of the Holocaust. Yet Witold’s reports smuggled out of the camp exposed to the outside world the events that are now so familiar. Just imagine being confronted with the atrocities of Auschwitz for the first time. Gas chambers. Daily transports of Jews being divided between those to be murdered immediately, and those to die a longer, slower death by starvation, hard labour and disease. Emaciated bodies. Random shootings and other acts of extreme violence. Obscene medical experiments. It is hardly surprising that some dismissed reports of the mass killings as fiction, they must have read like the script of a horror movie. But the Polish resistance in Warsaw took Witold’s reports seriously and used a network of underground couriers to bring news of atrocities committed at Auschwitz to the notice of the Polish government in exile in London and its leader Wladyslaw Sikorski. The experience of the couriers who carry his reports – transmitted verbally to Warsaw, then written up, microfilmed and sent to London – is an adventure story in its own right, fraught with danger at every turn. One courier, a Polish underground agent by the name of Napoleon Segieda, carried a microfilm with news of the first mass gassings of Jews in May 1942 in a false-bottomed suitcase from Poland via Austria, Switzerland, France, Spain, Gibraltar and Scotland finally reached London six months later. He called the delay “heartbreaking”. The Nazis had killed nearly a quarter of a million Jews in Auschwitz in that time. Sikorski repeatedly attempted to engage the British government to pay attention to the horrors committed in Nazi concentration camps in Poland and, from 1942, the mass murder of European Jews. I was deeply shocked to learn how much the Allied leaders knew of what was happening in Nazi-occupied Europe that they kept from the media and from the public, and refused to act on. Churchill and Roosevelt were both briefed repeatedly about the events taking place in Poland, but failed to comprehend the true nature of Auschwitz and its central role in Hitler’s plans. And from late 1942 reports emerged from other sources that backed up the smuggled information from inside Auschwitz. The Allied leadership knew what was happening, and yet they did nothing. Churchill over and again dismissed out of hand the idea of bombing the camp and its train lines, finding numerous excuses for inaction – he didn’t want to upset the local population with too many grim images, feared stirring up violent anti-Semitism at home, and was wary of reprisals against captured British airmen. Most damningly, he and Roosevelt believed bombing Auschwitz would a distraction from the overall war effort. Indeed, in early 1943, the US State Department even instructed its legation in neutral Switzerland to stop sending information from Jewish groups about the situation in Europe as they might inflame the public. Witold and his comrades continued to conduct their activities in Auschwitz – at huge personal risk and contending with sickness, hunger and deprivation – always with the expectation of support from the Allies that never materialised. Witold could not understand the lack of action, and wondered whether his reports were being intercepted and failing to get through to the Allies. He knew that a major uprising within the camp was destined to failure without help from outside, and several unsuccessful attempts to start a camp rebellion confirmed this belief. During Witold’s time in Auschwitz, many of his co-conspirators were discovered and killed. Having finally learnt that his reports from the camp had indeed reached the Polish resistance in Warsaw and travelled from there to London, but that international focus was elsewhere and few paid much attention to Auschwitz, Witold lost heart and began to plot his own departure from the camp. Miraculously, he and a colleague managed to escape in April 1943, but his work was not done. Witold continued his attempts to rally support among the Polish resistance for an attack on Auschwitz. But to his bafflement, his entreaties continued to fall on deaf ears. Few people in Poland were talking about the camp’s role in the murder of Jews, and meanwhile gangs of blackmailers roamed the streets in search of any Jews still in hiding. From outside the camp, Witold continued to write reports and to work for the Polish underground in spite of his increasing frustration. He survived the war and worked on his memoirs, but his story of futile heroism was forgotten. He was arrested by the Soviet authorities in May 1947 and sentenced to death at a show trial a year later. Had the outside world heeded Witold’s calls, millions of lives could have been saved. Churchill’s unwillingness to step in to help the Jews, Poles, gypsies, homosexuals, communists – all those deemed inferior by the Nazi ideology – brings me back to the current move to reassess many historical figures that have long been celebrated as national heroes. The recent wave of Black Lives Matter protests resulted in the toppling of statues of those who benefitted from the slave trade and colonialism. The statue of Churchill in London’s Parliament Square was vandalised then boarded up to prevent further damage by anti-racism protestors. Posterity has for too long airbrushed out the uncomfortable bits of history – the racism and bigotry that most of us today can no longer accept. That the tragic death of George Floyd spawned a worldwide movement to highlight inequality and bring institutional racism to the very top of national agendas is testament to how far we have come in 75 years. But it also highlights just how far we still have to go before all lives are considered equal irrespective of colour, creed, nationality or sexual orientation.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed