Since President Vladimir Putin’s announcement this week of a partial military mobilisation, Russian men have been fleeing the country in droves to avoid being called up to fight in Ukraine. Many flights to destinations that Russians can travel to without a visa – such as Turkey, Armenia and Azerbaijan – sold out within hours, with any remaining seats going for thousands of dollars. Photographs from Moscow’s international airport, Sheremetyevo, show terminals filled with men of fighting age, who reportedly face lengthy questioning before being allowed to leave. At border crossings to Georgia, Kazakhstan and Mongolia, the lines of cars stretch for several miles. Some have reached the border on bicycles to dodge the queues. Until now, Russia has relied on professional soldiers to fight in Ukraine, as well as paying generous sums to volunteers, and even convicted criminals, to join its forces. But Ukraine’s recent successes on the battlefield, winning back around 8,000 square kilometres of territory this month – mostly in the northeastern Kharkiv region – have prompted Putin to up the stakes. His escalation, announced on 21 September, involves the mobilisation of up to 300,000 reservists, threats to draw on Russia’s nuclear arsenal, and phoney referendums for parts of Ukraine under Russian occupation. These measures have triggered a watershed moment for a population that has been too scared to show dissent since the early days of the war. Thousands of Russians have joined street protests for the first time since March, when draconian laws were swiftly put in place introducing prison sentences of up to fifteen years for spreading disinformation about the war in Ukraine. The Russian anti-war group Vesna called for street demonstrations in all cities across Russia, with the slogan “No to mogilisation”, a morbid play on words, for mogila in Russian means grave. We could translate it as “mo-kill-isation”. “Thousands of Russian men – our fathers, brothers and husbands – will be thrown into the meat grinder of war. What will they die for? What will mothers and children shed tears for?” Vesna said in a statement. The latest protests are thought to have led to more than 1,300 arrests. Until now, the Russian population has been too cowed by fear to oppose the war – or deceived by state propaganda into supporting it. But this is beginning to change. The young men fleeing the country in droves know that there is a high risk that if they are sent to Ukraine, they will return in body bags. They know about the atrocious war crimes committed by Russian troops and want no part of it. Some are searching for medical exemptions rather than fleeing the country, citing mental health problems or treatment for drug addiction. The BBC quotes one young man in Moscow saying: “If you are stoned and get arrested while driving, hopefully you will get your licence taken away and will have to undergo treatment. You can't be certain but hopefully this will be enough to avoid being taken [into the army].” And another, in Kaliningrad: “I will break my arm, my leg, I will go to prison, anything to avoid this whole thing.” Dodging the draft is a criminal offence in Russia, and has been for a very long time. A century ago, my great uncle, Naftula Unikow, hid in a pile of grain in his grandfather’s warehouse when the Red Army came knocking at his door. He was trying to evade conscription for a Soviet counteroffensive against Poland in 1920, a conflict immortalised in Isaac Babel’s Red Cavalry short stories. Just like the young men fleeing Russia today, Naftula knew he would not be safe as long as he remained in the country. Together with a cousin who was in the same predicament, Naftula left his home near Kyiv at dawn in a rickety horse-drawn carriage which contained a hollow piece of metal with money hidden inside. To begin with, he sent regular telegrams home informing his family of his progress, but after a few days, the telegrams stopped. Weeks later, Naftula was finally able to send news again – he had only got as far as Kishinev (now Chisinau, capital of Moldova) where he was robbed by his own cousin, who stole not only the money hidden inside the metal bar, but also his ship pass and even his shoes. Naftula spent many months wandering from village to village, offering lessons in reading and writing in return for food, until finally he reached the port of Trieste in northern Italy. There he worked as a stevedore to raise enough funds to pay for his passage to Canada, where his grandfather’s brother was waiting for him. In all, it took him three years from leaving home to finally arriving in Winnipeg to join his relatives. Hopefully today’s fugitives will have a more straightforward journey. Photo: Vesna

0 Comments

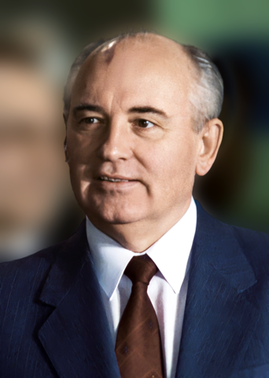

The late Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who died at the end of August, changed the course of my life. Back in the late 1980s, I had a university place lined up to study French and History. A couple of years earlier, Gorbachev had taken the helm of a superpower that was falling apart at the seams after years of stagnation and a decade of leadership by a succession of decrepit old men. Leonid Brezhnev, who died in 1982, had long been ridiculed for his senility and inability to walk unaided. He was succeeded by former KGB chief Yuri Andropov, who managed little more than a year in office, failing to appear in public at all for the last six months of his leadership. Next up was Konstantin Chernenko, who ruled for an even briefer period than his predecessor, before he fell into a coma and died in 1985. Just like the aging apparatchiks, the enormous country they ruled was in terminal decline. By comparison, the sprightly, 54-year-old Gorbachev was a breath of fresh air. As my own teenage interest in politics grew, so did the impact of the Soviet leader’s policies. I’d been fascinated by the Russian history topics I’d learned about at school: Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, the Russian Revolution. Now another revolution was beginning to take place before my very eyes. By the time I left school, glasnost and perestroika were starting to upend what the Soviet people thought they knew about themselves and their past, dismantling the dominance of the Communist Party and its grip on the nation. I was enthralled. I turned down my university offer and reapplied to different universities – ones with Russian departments – and signed up for a degree in Russian, to include a year studying in the USSR. At that point, the fact that my grandparents had emigrated from that very same country barely even crossed my mind. As I began my degree course, the Eastern Bloc was beginning to disintegrate. One month in, the Berlin Wall fell, and by the end of my first term the Cold War was officially over. In my second year, I studied a module titled Contemporary Soviet Society. A year later, Soviet society was no more, as the USSR fragmented into a myriad of constituent parts, many of them torn apart by war and civil unrest amid competing ethnic factions in a series of conflicts, some of which remain unresolved to this day. At the beginning of September 1991, I set off for the Soviet Union. Just two weeks earlier, Communist hardliners had attempted a coup against Gorbachev, imprisoning him at his dacha in Crimea and cutting off communications. Back home in the UK, I was glued to the news coverage. On arrival in Moscow, I travelled by bus from the airport to the station to catch the overnight train to Voronezh, the southern Russian city where I was to spend the next ten months. The bus passed the notorious KGB headquarters at Lubyanka, where a statue commemorating the founder of the secret police, Felix Dzerzhinsky, had acted as a centre point for mass protests against the coup leaders. Days earlier, the statue had been toppled and the pedestal was still daubed with graffiti. At the student hostel in Voronezh, people were talking of little else but the ‘putsch’, the Moscow protests, and the new president of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, who had rallied the crowd outside the Russian government buildings standing on the roof of a tank. Less than four months later, in late December, the Soviet Union fell apart. There were no mass street demonstrations this time, just a signing of official documents and some drab reports on the TV news. With hindsight, I feel that I experienced this pivotal moment of twentieth century history with my eyes shut, as day-to-day concerns took precedence over world affairs. Was there any hot water in the showers? When would the rubbish spilling from the bins in the kitchen finally be collected? Were paper cartons of milk really available at the kiosk downstairs and how long was the queue? Those turbulent years of empty shelves and endless queues ground down even the resilient Soviet people, many of them practically destitute as hyperinflation left their salaries and pensions worthless, or worse, unpaid. It is little surprise that Gorbachev was never as popular in the Soviet Union and its successor states as he was in the West, where he was lauded for bringing the Cold War to a peaceful conclusion. At home, Gorbachev’s dismantling of the command economy and the collapse of the Soviet Union heralded over a decade of chaos and economic turmoil, and turned a nuclear-armed superpower into a laughing stock. For this, Vladimir Putin and millions of other Russians will never forgive him. Photo: By RIA Novosti archive, image #29280/Yuriy Somov |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed