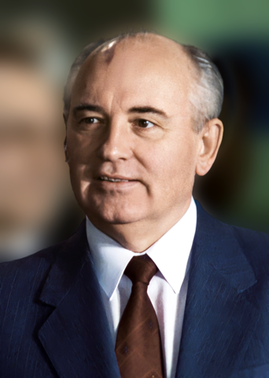

The late Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who died at the end of August, changed the course of my life. Back in the late 1980s, I had a university place lined up to study French and History. A couple of years earlier, Gorbachev had taken the helm of a superpower that was falling apart at the seams after years of stagnation and a decade of leadership by a succession of decrepit old men. Leonid Brezhnev, who died in 1982, had long been ridiculed for his senility and inability to walk unaided. He was succeeded by former KGB chief Yuri Andropov, who managed little more than a year in office, failing to appear in public at all for the last six months of his leadership. Next up was Konstantin Chernenko, who ruled for an even briefer period than his predecessor, before he fell into a coma and died in 1985. Just like the aging apparatchiks, the enormous country they ruled was in terminal decline. By comparison, the sprightly, 54-year-old Gorbachev was a breath of fresh air. As my own teenage interest in politics grew, so did the impact of the Soviet leader’s policies. I’d been fascinated by the Russian history topics I’d learned about at school: Peter the Great, Catherine the Great, the Russian Revolution. Now another revolution was beginning to take place before my very eyes. By the time I left school, glasnost and perestroika were starting to upend what the Soviet people thought they knew about themselves and their past, dismantling the dominance of the Communist Party and its grip on the nation. I was enthralled. I turned down my university offer and reapplied to different universities – ones with Russian departments – and signed up for a degree in Russian, to include a year studying in the USSR. At that point, the fact that my grandparents had emigrated from that very same country barely even crossed my mind. As I began my degree course, the Eastern Bloc was beginning to disintegrate. One month in, the Berlin Wall fell, and by the end of my first term the Cold War was officially over. In my second year, I studied a module titled Contemporary Soviet Society. A year later, Soviet society was no more, as the USSR fragmented into a myriad of constituent parts, many of them torn apart by war and civil unrest amid competing ethnic factions in a series of conflicts, some of which remain unresolved to this day. At the beginning of September 1991, I set off for the Soviet Union. Just two weeks earlier, Communist hardliners had attempted a coup against Gorbachev, imprisoning him at his dacha in Crimea and cutting off communications. Back home in the UK, I was glued to the news coverage. On arrival in Moscow, I travelled by bus from the airport to the station to catch the overnight train to Voronezh, the southern Russian city where I was to spend the next ten months. The bus passed the notorious KGB headquarters at Lubyanka, where a statue commemorating the founder of the secret police, Felix Dzerzhinsky, had acted as a centre point for mass protests against the coup leaders. Days earlier, the statue had been toppled and the pedestal was still daubed with graffiti. At the student hostel in Voronezh, people were talking of little else but the ‘putsch’, the Moscow protests, and the new president of the Russian Federation, Boris Yeltsin, who had rallied the crowd outside the Russian government buildings standing on the roof of a tank. Less than four months later, in late December, the Soviet Union fell apart. There were no mass street demonstrations this time, just a signing of official documents and some drab reports on the TV news. With hindsight, I feel that I experienced this pivotal moment of twentieth century history with my eyes shut, as day-to-day concerns took precedence over world affairs. Was there any hot water in the showers? When would the rubbish spilling from the bins in the kitchen finally be collected? Were paper cartons of milk really available at the kiosk downstairs and how long was the queue? Those turbulent years of empty shelves and endless queues ground down even the resilient Soviet people, many of them practically destitute as hyperinflation left their salaries and pensions worthless, or worse, unpaid. It is little surprise that Gorbachev was never as popular in the Soviet Union and its successor states as he was in the West, where he was lauded for bringing the Cold War to a peaceful conclusion. At home, Gorbachev’s dismantling of the command economy and the collapse of the Soviet Union heralded over a decade of chaos and economic turmoil, and turned a nuclear-armed superpower into a laughing stock. For this, Vladimir Putin and millions of other Russians will never forgive him. Photo: By RIA Novosti archive, image #29280/Yuriy Somov

1 Comment

Steve Davidson

7/9/2022 08:22:25 pm

Thank you for sharing your personal experience. I had wondered why and how you had taken up the study of Russia. Stay well; 'cause life is beautiful.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed