|

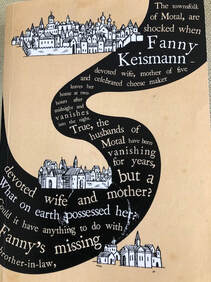

The images circulating in recent days of joyful Ukrainians celebrating the Russian retreat from Kherson tell a rare story of hope amid the devastation of war. Kherson was captured in early March, just days into the Russian invasion, and since then had remained the only Ukrainian regional capital under Russian occupation. For Moscow, the Kherson region provided a foothold west of the Dnieper river, a tactical location to facilitate a Russian push further west – to Odesa, seen as one of the most valuable prizes for Russian president Vladimir Putin. As well as being a key strategic port on the Black Sea, Odesa was known as the jewel in the crown of the Russian Empire, so called for its glorious situation, architecture and cultural heritage. Just a few short weeks ago, Putin announced with great fanfare that Russia had annexed the whole of the Kherson region – together with the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia – and that it would remain Russian forever. Moscow still claims this to be the case, but its words now ring hollower than ever. The liberation of Kherson feels like a watershed moment in the conflict, and it is little surprise that some have made historical comparisons with Stalingrad – the most crucial turning point of World War II. This brutal battle was fought from August 1942-February 1943 and finally resulted in a Soviet victory, triggering the German retreat from the Soviet Union. “After Kherson, it will be the turn of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, then Crimea. Or Crimea could be first, followed by Donbas, depending on how the situation plays out on the battlefield,” Roman Rukomeda, a Ukrainian political analyst, optimistically predicts. Whether the Russian retreat from Kherson indeed turns out to be a pivotal event in the Ukraine war remains to be seen. Kyiv remains wary of a Russian trap or ambush and consolidation of Russian positions east of the Dnieper raise fears of another bombing campaign. The recent heart-breaking BBC documentary Mariupol: The People’s Story offers a terrible reminder of the utter devastation that city and its population suffered under Russian bombardment earlier this year… …Which brings me to another World War II comparison from the same part of the world. SHTTL is a new film showing at the UK Jewish Film Festival this week, set in a Ukrainian shtetl near Ternopil close to the Polish border on the eve of the Nazi invasion in June 1941. Like the scenes in the BBC documentary of Mariupol and its inhabitants before the Russian invasion, the film depicts a location and way of life that is on the verge of vanishing completely. Its title, SHTTL, purposefully drops the letter ‘e’ to symbolise the disappearance of Jewish shtetl life and acts as a tribute to those who lived there. The action centres on Mendele, a young man returning to the shtetl to get married having left for Kyiv to pursue a career as a filmmaker. It follows his interactions with friends, family members and neighbours; their debates, discussions and arguments. Only the viewer knows, of course, that the wedding will never take place; that the community is about to be destroyed, its residents shot and buried in shallow pits. This is a Holocaust film with a difference, for rather than depicting death and suffering, it depicts life, with its diverse mix of joy and sorrow and disappointment. Written and directed by Ady Walter, and with dialogue entirely in Yiddish, SHTTL was filmed in a purpose-built village 60 kilometres north of Kyiv. The set includes a reconstruction of the only remaining wooden synagogue in Europe, which was blessed and consecrated to enable it to hold real-life prayer services. Household items from the 1940s were sourced from all over Ukraine. The village was intended to be transformed into an open-air museum to educate local schoolchildren and help Ukrainians to better understand their Jewish history and culture. The area north of Kyiv, of course, was under Russian occupation in the early weeks of the current war. The utter devastation wreaked by the Russian troops and their complete disdain for human life, as witnessed in Bucha, Irpin and elsewhere, leaves the museum project up in the air. “We don’t know what’s happened to it now,” Walter told the The New European. “We know it became a minefield around there and that there was heavy fighting, but we have no idea what has become of the construction.” Mariupol: The People’s Story is on BBC iPlayer in the UK and will be available on other BBC platforms for viewers elsewhere. SHTTL will be screened in London at the UK Jewish Film Festival at 6pm on Thursday 17 November. It is not yet on general release. A tour of the film set is available on YouTube:

0 Comments

I was invited to give a presentation at a Christian-Jewish church service with a theme of persecution and immigration, as part of this year’s North Cornwall Book Festival. The recent horror of refugees trying to flee Afghanistan in the wake of the Taliban victory, and the plight of migrants making perilous sea crossings in an attempt to reach Europe or the UK, have once again brought these issues to the fore. My own family lived through the pogroms, a series of anti-Semitic riots that took place in the Russian Empire, which in many ways served as a precursor to the Holocaust. Today, we would probably call the pogroms a form of ‘state-sponsored terrorism’ against Jews – supported and incited by the government, if not actually perpetrated by it. They began in 1881, when Jews took the blame for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, and continued in waves for the next 40 years, peaking in 1905 before coming to a head during the Russian Civil War – a chaotic and intensely violent period that lasted for about four years following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. During the civil war, the area where my family lived – near Kiev, in present day Ukraine – became a battleground with numerous armies criss-crossing the land – Communists, Nationalists, Anarchists, anti-Bolsheviks, peasant militias – all of them anti-Semitic to a greater or lesser degree. The White Army in particular, which was loyal to the Tsar – and backed by the West – introduced methods of mass murder of Jews that were later taken and pushed to their limit by the Nazis twenty or so years later. Many White Army soldiers later went on to join the Ukrainian militias that collaborated with the Nazis to destroy all Jewish life in Ukraine in the early 1940s. As well as the violence during the civil war, there was hunger. Food had become scarce during World War l, inflation soared making what little there was unaffordable, and the Bolsheviks requisitioned grain from the countryside (including from my great-great grandfather, who was a grain trader), to feed the workers in the towns. Not only did they take the grain, but also the seed, leaving the peasants with nothing to grow crops with the following year. The population was left to starve. My grandmother Pearl was around 17 years old at the start of the civil war, and an orphan. She lived with her grandparents, siblings and cousins and took it upon herself to become the family breadwinner, undertaking terrifying and dangerous journeys by train to markets across the region to buy, sell and barter what she could to keep her family alive. Eventually she even became a black-market gold dealer – taking any gold items belonging members of her local community on a murderous journey half way across Ukraine to exchange them for hard currency, which she brought back to the villagers so they could use it to buy food. Had she been caught, either with the gold or hard currency, she would have been shot. After more than three years of this perilous life that she hated with a passion, and following a particularly arduous trading trip when she was caught in a snowstorm and almost froze to death, she could take it no more. She decided she must try to get herself and her family out of the country. Six months later, in 1924, Pearl managed to emigrate to Winnipeg, Canada to join some other members of her extended family who had already made it out of Russia. She travelled alone, and with nothing. Once in Canada she did what so many immigrants do. She found a job and worked hard, scrimping, saving, and borrowing to raise enough money to bring the rest of her family over to join her the following year. Today my family is spread across Canada, from Vancouver to Toronto, and in America from California to New York, as well as in Germany, Israel and the UK, where they became, among other things, teachers and lawyers, journalists and doctors, Rabbis and social workers, all adding in their own unique ways to the prosperity and cultural life, as well as the wonderful diversity, of the places they now call home. Photo: Pearl (left) with her sisters Sarah (centre) and Rachel, circa 1920  Most Jews in North America and much of Europe can trace their roots back to the Russian Empire, once home to the world’s largest Jewish population. But how many of us actually understand how our families ended up there in the first place? The basics are fairly well known. After the Roman sacking of Jerusalem in 70AD, Jews scattered across the Roman Empire, which covered most of southern and western Europe and north Africa. By the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, the Jewish diaspora had spread right across Europe. The split into two distinct communities: the Sephardi on the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazi along the Rhine in Germany occurred around the 10th century. During the Crusades in the 13th-15th centuries, Jews were expelled from much of western Europe, including from England in 1291, France in 1343 and much of western Germany in the early 15th century. Many fled east, to the one country that offered a safe haven for Jews – Poland. Here King Casimir the Great (reigned 1333-1370) welcomed Jews for their trades and skills and protected them as “People of the King”. But by the 18th century, Poland was a weak and failing state, preyed on by its more powerful neighbours: Prussia, Austria and Russia. These three great European powers divided the country up between them in the three Partitions of Poland of 1772, 1793 and 1795. The area to the southwest of Kiev where my family came from became part of the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great in the second partition of 1793. Since 1991 it has been in independent Ukraine. Bert Shanas, a retired journalist turned genealogist from New York, has traced his family history to shtetls southwest of Kiev from at least the mid-1600s, and it is from his research that I have borrowed the contents and title of this article. The typical Ashkenazi Jew from this region, Shanas says, has an ancestral line that began in Africa, migrated to the Middle East, and from there into Europe, through France, to present-day Germany and into Poland, to an area that went on to become Russia then Ukraine over the course of some 200,000 years. Using a combination of DNA testing, recent scientific studies, archaeological discoveries, and biblical and historical scholarship, Shanas has traced the likely route his ancestors would have taken. His male family line would have had its origins in east Africa 60,000-70,000 years ago – around present-day Ethiopia, Kenya or Tanzania. Major climatic changes would probably have forced his ancestor to journey to the northeast in search of an adequate food supply, most likely travelling in a group of around 200 people. They would have crossed the Red Sea – then a smaller, shallower channel – into present-day Saudi Arabia and continued eastwards along the coast of the Arabian Sea until they reached the Indus Valley, the area that is today Pakistan. Thousands of years later, it is likely his ancestors would have broken off from the group and headed north through Iran to settle in what is now Turkey, around 40,000 years ago. About 10,000-15,000 years ago, they would have moved on to the Middle East, where Jewish history began – with Abraham, who came from the city of Ur in Babylonia, now southern Iraq - around 3,200 years ago. Shanas believes that following the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, his ancestors would probably have travelled from the Middle East through Turkey, Greece and Italy, then north through France around the year 1400 and from there to Germany. Around 1500, they would have moved east again, into Poland and by 1600-1700 were settled in the area near Kiev. DNA analysis indicates that Shanas’ female family line probably ended up in Poland by a different route, trekking north from the area around present-day Kenya or Ethiopia around 60,000 years ago, through Sudan and Egypt into the Middle East. They would have survived the last Ice Age somewhere around Mediterranean Europe and once the glaciers retreated, spread throughout Europe between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago. His ancestral line would probably have migrated to the Caucasus mountains then arced over the Black Sea into the Balkans. From there the DNA trail branches in two directions, the first heading north into Finland, passing through Poland on the way, and the second going west along the Mediterranean through France and Spain, into Portugal. DNA analysis shows that his genetic female ancestors were not grouped in great numbers in any one spot, but were scattered across eastern and western Europe, and their exact route to Ukraine is unclear. A study of the origins of Ashkenazi women by Professor Martin Richards at the University of Huddersfield in the UK and cited by Shanas in his research, found that in at least 80% of the cases studied, the DNA of Jewish women traced back to Europe – unlike that of men, which traced back to the Middle East. Richards concluded that the vast majority of Jewish men who fled the Middle East for Europe after the Roman conquest did not take women with them. Instead, they married local European women, who then converted to Judaism. With grateful thanks to Bert Shanas for allowing me to use his research for this article. As another lockdown Passover begins, I’ve been reflecting on this Passover story that dates back nearly a century, to the late 1920s. My great-grandmother’s cousin Babtsy arrived in Winnipeg, Canada, with her husband Moishe and four children at the end of their long journey from Kiev, which at that time had recently become part of Soviet Ukraine. Babtsy and Moishe had survived a terrible pogrom in their home town of Khodorkov in 1919. The town’s Jews had been rounded up and herded to a sugar beet factory beside a lake, then forced to keep going deeper into the lake until they drowned or froze to death. Babtsy and her family had hidden in a basement and, when it was safe to emerge, they found houses smouldering around them and the lakeside littered with pale corpses. Barely stopping to grab a handful of belongings, they fled to the railway station and took the first train to Kiev, where they remained for several years, living with Moishe’s parents. Owing to a mixture of errors, misunderstandings and delays, it took three and a half years from the time they first lodged their application to emigrate to Canada to their eventual arrival in Winnipeg. Remarkably, our family has around 50 pages of documentation relating to this process, consisting of letters between the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society Western Division in Winnipeg, its head office in Montreal, and the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization in Ottawa. I have written about this in a previous article, which you can read here. Once Babtsy, Moishe and their children finally arrived at the Canadian Pacific Railway Station in Winnipeg, they asked the station master to call the phone number of Babtsy’s cousin Faiga. Faiga had been the first member of our family to leave the Russian Empire for Winnipeg back in 1907 with her husband, Dudi Rusen, and one of her brothers. Dudi was an ambitious young man. Once in Winnipeg he bought a pushcart and based himself on a street corner to sell fruit and vegetables. He worked hard and after a while had raised enough money to buy a truck, then within a few years he was running his own wholesale produce company. Faiga and Babtsy had not seen one another for more than 20 years. Faiga and Dudi, with their children and grandchildren, were in the middle of a Passover Seder when the station master rang on that spring evening. Dudi answered the phone and told him to put the newly arrived family in a taxi and send them straight to his home at 107 Hallett Street. To great excitement, everyone budged up around the table to make space for the relatives from the Old Country so they could join the Seder, and celebrate this latest escape of Jews, to a new Promised Land, alongside the ancient exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. This Passover story is narrated in the following clip by Monty Hall, the host of TV’s Let’s Make a Deal. Monty was Faiga and Dudi Rusen’s grandson and was at their house that evening during Passover. In the video, Monty describes his tremendous excitement at reading my book, A Forgotten Land, and discovering that it was about his own family. Monty contacted me after he read the book and we had a long telephone conversation, during which he recounted this Passover story to me. After many years hosting Let’s Make a Deal, Monty Hall engaged in philanthropic work, helping to raise close to a billion dollars for charity. He features in both the Hollywood and Canadian Walk of Fame, and the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs, California, and was awarded the Order of Canada in 1988. He died on 30 September 2017 at the age of 96.  The story of the Jewish shtetl is well known. These once vibrant communities that were so widespread across Eastern Europe until the 20th century were destroyed, first by pogroms and resulting waves of emigration, and later by the anti-religion policies of the Soviet Union, with their final remnants wiped off the face of the earth by the Holocaust. But not so, it seems. A new documentary from the Russian filmmaker Katya Ustinova explores the existence of shtetls in Ukraine and Moldova right up until the 1970s and even beyond. Shtetlers premiered last year and was available to view during Russian Film Week USA in January. Unfortunately, is not yet available in Europe, so I am still awaiting an opportunity to watch it. As the film’s website says, “In those small and remote towns of the Soviet interior, hidden from the world outside of the Iron Curtain, the traditional Jewish life continued for decades after it disappeared everywhere else. The tight-knit communities supported themselves by providing goods and services to their non-Jewish neighbours. The ancient religion, Yiddish language and folklore, ritualised cooking and elaborate craftsmanship were practised, treasured and passed through the generations until very recently.” Ustinova is a Russian-born documentary maker living in New York who previously worked as a producer, host and reporter for a Russian broadcasting company in Moscow. Shtetlers is her first feature-length film. Ustinova’s grandfather was a Jewish playwright, but her family did not identify as Jewish until her father, a businessman and art collector, founded the Moscow-based Museum of Jewish History in Russia in 2012. On discovering modern artifacts from shtetls in the former Soviet Union, Ustinova and her father came to realise that some Jewish communities had continued to exist for far longer than they had thought. Shtetlers tells the stories of Jews in these forgotten shtetls by means of nine first-hand accounts of people who lived in them. In 2015, Ustinova visited several former shtetl residents, who have since scattered around the world. Many of the stories in Shtetlers help break down the myth that only enmity existed between Ukrainians and Jews. Without distracting from the fact that many Ukrainians committed atrocities against the Jewish population before and after – as well as during – the war, the film reminds us of those gentiles who loved and cared for their Jewish friends and neighbours. Meet Vladimir. He was not born Jewish, but converted after his mother – who is honoured at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Centre – sheltered dozens of Jews during the war. Growing up among Jewish neighbours, their culture imbued itself into gentile homes, and he remembers his mother baking challah during his childhood. Vladimir emigrated to Israel and now lives in the West Bank as part of an Orthodox Jewish family. And Volodya and Nadya, Ukrainian farm workers still resident in a former shtetl in Ukraine, who remembered their Jewish neighbours so fondly that they decided to adopt Jewish customs, like making matzo brei and kissing the mezuzah attached to the doorway of their house – which once belonged to Jews – when they enter. Emily, a Jewish shtetler who survived the war, escaped from a concentration camp and was saved by a gentile friend – the sister of a Ukrainian police chief – who brought her family food while they were in hiding. And then there’s the queue of Russian Orthodox Christians coming to Rabbi Noah Kafmansky to solve their problems and obtain his blessing, because “the Jewish God helps better”. In the five years since Ustinova filmed Shtetlers, many of the people she met have passed away. “Their memories are a farewell to the vanished world of the shtetl, a melting pot of cultures that many nations once called their home,” the website says. The trailer is available on the Shtetlers website: shtetlers.com/ And numerous extracts from the film, as well as some gorgeous animated clips, can be found on the Shtetlers Instagram page: www.instagram.com/shtetlers/  Antony Blinken is on the cusp of being appointed Secretary of State in the new administration of President Joe Biden. One thing many people may not know about Blinken is that his great-grandfather was a Yiddish writer of some repute. Meir Blinken was born in 1879 in Pereyaslav, Ukraine – coincidentally the same shtetl as Yiddish literature’s most famous name, Sholem Aleichem. Blinken gained a Jewish education at a Talmud Torah, before attending the secular Kiev commercial college, part of a joint educational project founded by Ukrainian and Jewish businessmen. He worked as an apprentice cabinet-maker and carpenter, before switching to become a massage therapist. Indeed, he is listed in the Lexicon of Modern Yiddish Literature with the trade of masseur. His son Moritz, Tony Blinken’s grandfather, who became an American lawyer and businessman, was born in Kiev. Blinken Senior emigrated to the US in 1904. His first story, written under the pen-name B Mayer, was published a year earlier, in 1903. Once in America, his sketches and stories appeared in a range of literary, progressive socialist and labour Zionist publications, including the satirical magazine Der Kibetzer (Collection) and Idishe Arbeter Velt (Jewish Workers’ World) in Chicago. In all, he published around 50 works of fiction and non-fiction. Blinken’s books include Weiber (Women), described in the lexicon as a prose poem, Der Sod (The Secret) and Kortnshpil (Card Game). A collection of his short stories published in 1984 and translated by Max Rosenfeld, is still available. His writing dealt with thorny topics including the effects of poverty, poor living conditions, religious strictures, inadequate education and the lack of understanding that immigrants feel about their new country. Most controversially, he was one of the few male Yiddish writers to address the subject of women’s sexuality, writing about marital infidelity and sexual desire and hinting at the sense of boredom felt by housewives. Another subject he tackled remains controversial to this day: showing empathy towards abortion. Writing in a review of Blinken’s work in the 1980s, the journalist and author Richard Elman pointed out that among Yiddish authors writing for the largely female audience of Yiddish fiction, Blinken “was one of the few who chose to show with empathy the woman’s point of view in the act of love or sin”. Elman and others believed that the greatest legacy of the author’s work was that it vividly evoked the atmosphere and characters of the very early Jewish diaspora in New York. According to a 1965 article by the journalist David Shub in the Jewish newspaper The Forward, Blinken was the first Yiddish writer in America to write about sex. In the same article, he wrote that Blinken was also an editor’s nightmare! By the time of his death in 1915 at the age of just 37, Blinken had opened an independent massage office on East Broadway, in the heart of what was at that time the city’s Yiddish arts and letters district. While his writing was very popular among Yiddish-speaking Americans of his own generation, Blinken’s star quickly waned after his death. Photo credit: Ukrainian Jewish Encounter  When I first began writing my grandmother’s story and turning her recollections into what would eventually become a book, the title I originally had in mind was The Breadbasket. To me, this encompassed much what the people and places in the book were about. Ukraine was known as the Breadbasket of Europe because of its huge grain production. My great-great-grandfather Berl was a grain trader. And bread, or lack of it, played a big role in the family story, from the mill my family owned in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th, to the prosperity Berl built through his thriving business, to his wife Pessy’s ability to make a ball of dough dance as she kneaded and shaped it in mid-air, and the challah on the Sabbath table. And later, there were the Bolshevik grain requisitions, the great hunger that followed the revolution when there was no bread to be had and my grandmother travelled the land with a basket on her back, bartering food to keep her family alive. But a literary editor who guided my early manuscript advised me to ditch the title. You need something more evocative and compelling, he said. Several weeks later, I finally settled on A Forgotten Land. This was a success and I was pleased with the change. The new title evoked the terrible loss suffered by towns and villages across a wide swathe of Eastern Europe, along with the people who lived there and their way of life. In the Pale of Settlement of the Russian Empire, pogroms, war, famine, disease and emigration had torn Jewish families apart from the 1880s onward and seared the heart out of Jewish communities. The Nazis, of course, would do the rest, not just there but across Europe. The Pale did indeed become a forgotten land, a network of once vibrant communities whose people had all emigrated or died. Three-quarters of a century on from the Holocaust, many people are working hard to bring to light the remnants of the deserted shtetls, to remind us of these communities that have been forgotten for so long. I will highlight just two projects, but please feel free to add others to the comments at the end of this article. The first is a blog called Vanished World, which documents Cologne-based photographer and writer Christian Herrmann’s travels around Eastern Europe and elsewhere in search of visual traces of the Jews who once lived there - destroyed or misappropriated synagogues, overgrown cemeteries, tombstones in the street paving, traces of home blessings on door jambs. “Neglected Jewish cemeteries, ruins of synagogues and other remains of Jewish institutions [are like] stranded ships at the shores of time. The traces of Jewish life are still there, but they vanish day by day. It’s only a matter of time until they are gone forever,” he says. His articles and photographs are both a commemoration and an act of justice towards the men, women and children who died as innocent victims in the Holocaust, and an act of justice to those who survived as well. Christian’s photographs are beautiful and his commentaries on his travels tell a repeated and all-too- depressing tale of crumbling synagogues that were later used as museums, offices or factories during the Soviet era, fragments of tombstones incorporated into buildings or unearthed during construction works, and long-forgotten Jewish cemeteries that are now parks or wastelands. Another project is taking place in Ukraine, where Vitali Buryak, a software engineer from Kiev, has taken on the immense task of attempting to catalogue hundreds of shtetls. He began by creating lists of every settlement with a historical Jewish population of more than 1,000 for each gubernia (province) in central and eastern Ukraine. “My plan is very simple – to write at least a small article for each place on my list,” he says. His articles include old photographs and maps, archival documents, historical references and information about local families as well as numerous photographs of his own. Vitali only recently learnt of his own Jewish roots, and decided to offer his services as a tour guide for Jewish visitors from abroad. One of his early tours brought him to the town of Priluki. “Priluki is the place where I was born, and my grandma is still living there. I contacted the head of the local Jewish community and he showed me places that I didn’t know about before! In my city, where I was born! My grandma didn’t show me the synagogues, she didn’t show me Jewish cemetery, she didn’t show me the Holocaust killing sites, or the sites of the ghetto. I’ve walked on this street, I’ve seen this building before. But I didn’t know it was a synagogue. And it was a shock for me,” he recounts. “I decided to make this website in dedication to the Jews of Ukraine. The purpose of it is the gathering of information and resources from the remaining Jewish communities in Ukraine, as well as the ones that have been destroyed” Vitali says. Vitali’s website can be found here http://jewua.org/ And the Vanished World blog can be found here https://vanishedworld.blog/  In recent webinar presentations I’ve given, one topic that tends to generate a lot of interest and provokes many questions and discussions is that of Jewish conscription to the Russian army in Tsarist times. One particularly brutal and terrifying experience for our forefathers was the arrival of happers to take the family's sons away. In 1827, during the reign of Tsar Nicholas I, the government ordered a quota system of compulsory conscription of Jewish males aged 12 to 25 to the army (for Christians it was 18 to 35). The quota was higher for Jews – part of the Tsar’s effort to refashion and forcibly assimilate the Jewish population. The kahal, or local administration, run by leading members of the Jewish and Rabbinical community in each locality, was responsible for selecting the recruits. The selection process was often arbitrary and influenced by bribery, turning Jews against their communal leaders. By the 1850s, the happers had taken to kidnapping Jewish boys, sometimes as young as eight if they couldn’t lay their hands on enough older boys, in order to meet the government’s quotas. The drafting of children lasted until 1856. Once conscripted, the young Jewish recruits were pressured to convert to Russian Orthodoxy, with the result that around one-third were baptised. Their military service lasted 25 years. As described in my book, A Forgotten Land, the happers spread fear across the Pale of Settlement, and with very good reason: “It took only days for the Jewishness to be squeezed out of the recruits like water from a sponge. They were barred from following the kosher laws or keeping the Sabbath, or even from speaking Yiddish. Anyone who insisted on holding fast to the dietary laws – refusing to eat pork or soup made with lard – was beaten with a rod or forbidden from drinking. But however firm their Jewish resolve, there was no way the boys could avoid marching or performing drills on the Sabbath. At the end of a ten-hour march, having eaten nothing but dry bread, the young recruits would arrive exhausted at their destination and be forced to kneel until they agreed to convert to Christianity. If they continued to refuse, they had to kneel all night.” My great-great-great grandfather had all his teeth pulled out to avoid being taken by the happers during the Crimean War of 1853-56, as the army would not accept recruits who had any kind of deformity. He never had a pair of false teeth, so the extractions altered his appearance for life. Other young men turned to self-mutilation to avoid conscription, cutting off fingers or toes, or even blinding themselves or wielding a red-hot poker to the face. I have just watched a beautiful and fascinating short film (just 18 minutes long) directed by Jacob Stillman depicting the role of the happers and the terror they spread among Jewish communities at this time. The film, released in 2013, is called simply The Pale of Settlement. It is set in 1853 in the Carpathian Mountains on the western reaches of the Russian Empire. The opening scene shows a young boy cutting wood in the snow near the forest hut where his family lives. He watches as happers approach on horseback, rounding up recruits for the Crimean War. Ten-year old Moishe hides in the trees as the men, accompanied by a Cossack horseman, knock at the door of the family home. Moishe’s father tells them, “Let me talk to the kahal. They know me, they would never choose my son.” One of the men replies, “The kahal sent us.” Moishe overhears the conversation, screams and runs deeper into the forest to hide, pursued by the happers. His initial effort at taking refuge with a neighbour has the most horrific consequences. I won’t give away any more plot spoilers, I simply urge you to watch the film for yourself. It gave me a much better sense of who the happers were and just how frightening their arrival would have been. This moving film is dedicated to the memory of all the child victims of the happers. The Pale of Settlement is available to watch free on Vimeo: https://vimeo.com/70219384  One of the most original and unusual books I’ve read in a long time is The Slaughterman’s Daughter by Yaniv Iczkovits, a recent release, translated from the Hebrew, from the always impressive MacLehose Press – a UK publisher that specialises in works in translation. Set in the Pale of Settlement of Imperial Russia at the end of the 1800s, it tells the story of Fanny Keismann, the eponymous daughter of a kosher butcher, who goes in search of her brother-in-law, Zvi-Meir, after he abandons her sister and their two children. Fanny’s journey to Minsk – now the capital of Belarus and recently in the news for mass protests against its tinpot dictator Alexander Lukashenko who refuses to give up power – is fraught with danger. Fanny’s talent with a butcher’s knife stands her in good stead to quell her foes, but it also sets in train a fantastical series of events that spiral out of control and, unsurprisingly, get her into trouble with the law. Like the stories of Sholem Aleichem, this book and its cast of motley characters evokes a nostalgia for the shtetls of Belarus, Ukraine and elsewhere in the region before the Russian Revolution, and a way of life that was already beginning to unravel when this novel was set. Hundreds of thousands of Jews had begun to emigrate to the west (mostly the United States) in search of an escape from discrimination, anti-Semitic violence and economic hardship from the 1880s onwards. Later, of course, during the Nazi occupation of 1941-44, the shtetls were destroyed altogether, their inhabitants murdered or, in the case of a lucky few, forced to flee eastwards in a bid for survival. It is impossible not to feel a deep regret for the disappearance of these vibrant communities where our ancestors lived for generations, settlements that were extinguished so brutally. I for one am fascinated by stories and images of the lost Jewish world of Eastern Europe. But the shtetls were home to a way of life that was tough and unenviable, as this novel demonstrates. They were generally poor, miserable places, where, “The Jews have huddled so close to each other that they have not left themselves any space to breathe”. And where Jew and Goy often distrust one another absolutely. For most of us with origins in the kinds of places that Iczkovits writes about, when we think of this period of history what we remember are the pogroms – the brutal anti-Semitic violence that broke out periodically in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This book, filled with black humour and deep affection, but also gritty realism, provides a wonderful illustration that there was much more to this time and place. The author describes a way of life where, outdoors, “The market is a-bustle with the clamour of man and beast, wooden houses quaking on either side of the parched street. The cattle are on edge and the geese stretch their necks, ready to snap at anyone who might come near them. An east wind regurgitates a stench of foul breath. The townsfolk add weight to their words with gestures and gesticulations. Deals are struck: one earns, another pays, while envy and resentment thrive on the seething tension. Such is the way of the world.” Meanwhile, indoors, mothers share a bed with their multiple children and face continual curses and criticism from their in-laws in the next room, who treat them like servants. Yaniv Iczkovits is an Israeli born of Holocaust survivors. “What I wanted to do was to bring these forgotten memories of this lost world into 21st century Israel, and to present the richness of a culture that is now gone, but is still a major part of who we were and what we are,” he says.  My second and final post based on the publication A Journey through the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter looks at issues of assimilation and emigration. The Journey is a fascinating document published last year by a private multinational initiative called Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter aimed at strengthening mutual comprehension and solidarity between Ukrainians and Jews. Jewish assimilation in the Russian Empire wasn’t necessarily a question of choice. The government of Tsar Nicholas I enacted measures to refashion and forcibly assimilate the Jewish population. In 1827, it ordered a quota system of compulsory conscription of Jewish males aged 12 to 25 (for Christians it was 18 to 35) to the Tsarist army and made the leadership of each Jewish community responsible for providing recruits. The selection process was often arbitrary and influenced by bribery, turning Jews against their communal leaders. By 1852–55, so-called happers were tasked with kidnapping Jewish boys, sometimes as young as eight, in order to meet the government’s quotas. As described in my book, A Forgotten Land, the happers spread fear across the Pale of Settlement. Once conscripted, the young Jewish recruits were pressured to convert to Russian Orthodoxy, with the result that around one-third were baptised. The drafting of children lasted until 1856. Other assimilationist measures included the establishment of state-sponsored secular Russian-language schools for Jewish children and rabbinic seminaries to train ‘Crown Rabbis’ who were expected to modernise the Jews. An 1836 decree closed all but two Hebrew presses and enacted strict censorship of Hebrew printing. In 1844 the kahal system of Jewish autonomous administration was abolished. Decrees were also passed on how Jews should dress and the economic activities in which they were allowed to engage. The Jewish Enlightenment – an intellectual movement across central and eastern Europe promoting the integration of Jews into surrounding societies – helped to further the aims of the tsarist government. Activists known as maskilim were enlisted to censor Jewish religious books, as these were considered to promote fanaticism and be an obstacle to Russification. A series of laws and decrees improved the situation of the Jews under Tsar Alexander II (1855-81). Conscription requirements became less severe, while some Jews were allowed to reside outside the Pale and to vote. Political and social reforms enabled the first generation of Jewish journalists, doctors, and lawyers to obtain degrees at the state-sanctioned rabbinic seminaries and universities, going on to form the core of a modernised Jewish intelligentsia. Journalists and writers, often from the ranks of the maskilim, began to publish Russia’s first Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian-language Jewish newspapers. Modernist synagogues were established. But state-sponsored discrimination against Jews continued, as did anti-Semitic articles in the Russian press and the expulsion of Jews deemed to be residing in Kiev illegally. The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 triggered a new round of repression, with Jews banned from certain professions and geographical areas, and political and educational rights restricted. Only Jews who converted to Orthodox Christianity were exempt from the measures. By the late 1800s, a small group of prosperous Jewish traders had emerged, but the vast majority of Jews lived a modest existence that often bordered on poverty. According to the Jewish Colonization Society, in 1898 the poor comprised 17-20% of the Jewish population in several provinces of present-day Ukraine. But worse than the grinding poverty and discrimination were the pogroms. Derived from the Russian verb громить (gromit’), meaning to destroy, pogroms were waves of violent attacks on Jews that took place across the Pale primarily in 1881-82, 1903-06, and 1918-21. Alexander II’s assassination triggered mobs of peasants and first-generation urban dwellers to attack Jewish residences and stores. Of 259 recorded pogroms, 219 took place in villages, four in Jewish agricultural colonies, and 36 in cities and small towns. Altogether 35 Jews were killed in 1881–82, with another 10 in Nizhny Novgorod in 1884. Many more were injured and there was considerable material damage. A second wave of pogroms began in 1903 with an outbreak of anti-Semitic violence in Kishinev, in which the authorities failed to intervene until the third day. Further pogroms followed Tsar Nicholas II’s manifesto of 1905 that pledged political freedoms and elections to the Duma. The mass violence was orchestrated with support from the police and the army and carried out by the ‘Black Hundreds’ – monarchist, Russian Orthodox, nationalist, anti-revolutionary militants. Around 650 pogroms took place in 28 provinces, killing more than 3,100 Jews including around 800 in Odessa alone. Jews attempted to resist pogroms in many areas by organising self-defence groups. Many were community-organised, but the Jewish Labour party or Bund also began mobilising self-defence units in the early 20th century. The 1881–82 pogroms set in motion new political and ideological movements, and led to large-scale emigration. For many Jewish intellectuals, the goal of integration and transformation of communities through education and Russification was now discredited. Some perceived socialism, with its promise of equality, as the solution; others promoted emigration to America or Palestine. By the end of the nineteenth century, both Jews and Ukrainians began to emigrate in large numbers, mostly to North America. In 1882 Leon Pinsker, a physician from Odessa who had earlier promoted the integration of Jews into broader Russian society, published an influential pamphlet titled Autoemancipation, in which he advocated that Jews establish a state of their own. He proceeded to found the Hibbat Zion movement, which paved the way for the Zionism. In 1882–84 some 60 Jews from Kharkov moved to Palestine, the first mass resettlement of Jews in Israel. From 1897 Zionist circles were established in several Ukrainian cities, making the region a centre of organised Zionism. The Tsarist government was initially indifferent towards the Zionists, but eventually banned them. According to the 1897 census, 2.6 million Jews lived on the territory of present-day Ukraine. Kiev and some other provinces had a Jewish population of around 12-13%, while in Odessa, Jews made up almost 30% of the population. Of the Jewish population, more than 40% were engaged in trade, 20% were artisans and 5% civil servants and members of ‘free professions’, such as doctors and lawyers. Just 3-4% were engaged in agriculture, in contrast to the vast majority of the Ukrainian population. Given these figures, the scale of emigration was immense. More than two million Jews migrated to North America from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1914, mainly from lands that make up present-day Ukraine. Of these, about 1.6 million came from the Russian Empire (including Poland), and 380,000 from provinces of western Ukraine that were at the time part of Austria-Hungary (mainly Galicia). Another 400,000 Eastern European Jews migrated to other destinations, including Western Europe, Palestine, Latin America, and southern Africa. Jews comprised an estimated 50 to 70 percent of all immigrants to the United States from the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1910. About 10,000 Jews had arrived in Canada by the turn of the century, rising to almost 100,000 between 1900 and 1914, settling mostly in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, the hub of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where my own family settled. Click here to see the document on which this article is based https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/media/UJE_book_Single_08_2019_Eng.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2D2QAuBtjsIqF1kHi4eRUlxBZT-UFPR3usj0741Cp3nnnouJT1icJGphM |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed