Ten years ago I travelled with my Dad to America for a family visit. It was the first time I had met most of his first cousins – and it turned out to be the last time I saw his sister, my dear aunt Lil, who died a few years later. One of Dad’s relatives, irrepressible and wonderful cousin Betty, is a psychic and clairvoyant. Betty is much on my mind at the moment as wildfires rage around Los Angeles, forcing her to evacuate her home. “I know you are a writer, but have you ever thought about doing documentaries?” she asked me back in 2008. “I’d love to make documentaries!” I replied. “Well, you will.” And today, ten years on, the first documentary I have been involved in is being broadcast on the BBC's World Service radio station. It’s a ten-minute piece about the lost Jewish world of the Eastern European shtetl, using anecdotes recounted by my grandmother about her early life back in Ukraine – then part of the Russian Empire. Mostly when I give talks about my work, I focus primarily on the dramatic major events that affected Russia’s Jewish community at the time – pogroms, World War I, the Russian Revolution and civil war. But the documentary concentrates on more mundane aspects of day-to-day life, such as Sabbath rituals in my grandmother’s house, relations with the local Ukrainian population, the Rabbi’s court where members of my family lived and worked, and a crazy and somewhat comical incident that landed my great-great grandmother in jail, to the horror and embarrassment of the whole family. The documentary is based on snippets of recordings made by my father back in the 1970s of my grandmother telling stories about her early life in Russia. They are recorded in Yiddish, the language of the Jews of Eastern Europe. It is a language once spoken by around 12 million people that transcended national boundaries, but which was almost wiped out by the holocaust. The vast majority of the Jews killed in the Nazi death camps would have spoken Yiddish as their mother tongue. Today the language is undergoing something of a revival, in the US in particular. Surprisingly there are still up to two million Yiddish speakers in the world. You can sign up to Yiddish evening classes, watch Yiddish theatre performances and attend Yiddish dance parties. In 2017, the Yiddish Arts and Academics Association of North America was born, with a mission to promote Yiddish language and culture through academic and artistic events and through Yiddish food. “The goal,” says founder Jana Mazurkiewicz Meisarosh, “is to make Yiddish culture hip, modern and interesting.” In the US, “Yiddish has been trapped within two discrete, hermetic spheres: the ultra-Orthodox sphere, which engages the religious aspects of Yiddishkeit, and the academic sphere, which tends to study secular Yiddishkeit of the past. As a result, Yiddish language and culture … is often viewed as a relic of the past, and fails to find resonance in daily life and modern culture,” she says. It’s a fascinating and worthy goal, to bring back to life a language that came close to extinction. The culture of the shtetl is unlikely to be reborn outside of the most restrictive Jewish communities, but if it can gain further resonance in today’s world, this is surely something to celebrate. Listen to the documentary here: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cswsp3

0 Comments

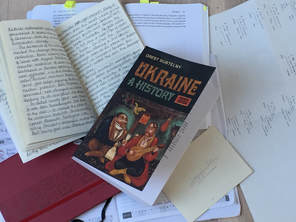

My great as-yet-unwritten novel has not yet started to take form, but its shape is finally becoming slightly less amorphous. The notes on historical background are burgeoning in the lovely soft-backed notebooks with cream-coloured pages that I treated myself to in the hope that they would help inspire my writing. I recently embarked on a dauntingly enormous tome that has been sitting beside my sofa for many months, taunting me with its great heft. At nearly 800 pages, Ukraine: A History by the academic Orest Subtelny, promises to be a valuable resource, but perhaps one that I shall dip into rather than reading from cover to cover in my usual methodical way. I like the book’s dedication: "To those who had to leave their homeland but never forgot it" – people like my grandparents who circumstance forced to travel thousands of miles to forge a new life in Canada. Grandma certainly never forgot her homeland. She talked about it endlessly, so much so that her children – my Dad and aunt – grew up surrounded by her stories, and the inhabitants of a distant Ukrainian village – many of them long dead – seemed more real to them than those of the Canadian city in which they lived. The period that interests me most is the Russian civil war of 1917-22. The book refers to this era as the Ukrainian Revolution. These two events were intertwined, each an integral part of the other. After the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in October 1917, the revolution turned to civil war as, in Subtelny’s words, “numerous claimants for power in Ukraine and throughout the former empire were embroiled in a bitter, merciless military struggle, complete with large-scale terror and atrocities, to decide who and what form of government should replace the old order”. These “claimants for power”’ were what my grandmother called the banda. They were “rebels and hoodlums, peasants and ex-army officers representing every kind of faction, every ideology imaginable. Some fought for Communism, others for Nationalism, Anarchism, Freedom or Holy Russia. Each recruited fighters to his cause, often luring the impoverished and the illiterate with the promise of food and action, arming them with guns brought back from the war – the other war – and hidden in hayricks or underground hideouts. “It seemed that each banda was competing to be more bloodthirsty than the last. They appeared to take pride in acts of rape and pillage, mutilation and murder. Their armies were each represented by a colour, like pieces in a giant board game. Every banda was competing against all the others, occasionally forging an alliance to gang up on one enemy, only to break the pact a few months later and start fighting again. There were Reds, Whites, Greens and sometimes even Red-Greens and White-Greens and names that instilled fear: Petlyura, Makhno, Zeleny, Denikin. The Greens took their name from their little flat caps and those of Zeleny’s men were yellow. Makhno’s anarchist fighters wore black hats and carried black flags crudely painted with the words ‘Liberty or Death’. The Cossack fighters had scarlet caps, while the Bolsheviks decorated their arms with thick, blood-red bands. As well as those sporting what could pass for a uniform, there were other banda made up of rag-tag bunches of ruffians.” One of the key turning points of the Ukrainian Revolution took place exactly a century ago, in November 1918. Ukraine had been ruled since April of that year by a regime known as the Hetmanate, a conservative Ukrainian government headed by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky – his title evoking Ukraine’s old Cossack traditions. The Hetmanate existed under German occupation and replaced Ukraine’s year-old Central Rada, a broad but mostly nationalist and socialist council, or soviet, which had come to power following the Russian Revolution. Skoropadsky was a wealthy landowner and part of the Tsarist establishment, but had thrown off his imperialist veneer to become leader of a Free Cossack peasant militia and set about dismantling some of the left-wing policies imposed by the Central Rada. He bestowed on himself sweeping powers and declared the establishment of the Ukrainian State. New Ukrainian-speaking schools popped up across the land, Ukrainian-language school books were hastily published and even two new Ukrainian universities were created. But opposition to Skoropadksy and the Hetmanate soon mounted and spontaneous, fierce peasant revolts spread across Ukraine. Led by local, often anarchistic, leaders known as an otaman or batko, hordes of peasants fought pitched battles against the occupying German troops. The insurrection centred on a town called Bila Tserkva, just west of Kiev and only a few miles from my family’s home in Pavolitch. Thousands of peasant partisans poured into the area. By 21 November they had encircled Kiev and three weeks later the occupying Germans evacuated the city, taking Skoropadsky with them. As a result of the fall of the Hetmanate, the following year total chaos would ensue, but the story of 1919 is one that I will save for later. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed