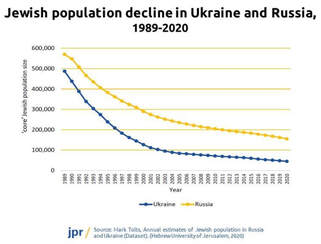

Since February 2022, more than six million Ukrainians have fled abroad in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Another 8 million are internally displaced, mostly in western Ukraine. And around a million Russians have also escaped abroad, many because of their opposition to the war or to avoid the draft under Russia’s partial mobilisation. Among these numbers are tens of thousands of Jews. According to Israel’s Ministry of Aliyah and Integration, more than 40,000 immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus in the year to February 2023. Many members of the Ukrainian Jewish community have also found refuge in other European countries, but those who arrived in Israel held an advantage in having an immediate right to citizenship. The number of Ukrainians with at least one Jewish grandparent – and therefore qualifying for Israeli citizenship by Israel’s Law of Return – was 200,000 in 2020, according to the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR), while the number who identify as Jewish (the ‘core’ Jewish population) was estimated at 45,000. Since the end of the Cold War, the Jewish population of Russia and Ukraine has fallen by 90%, according to the JPR, continuing an exodus that had begun in the early 1970s. An easing of the ban on Jewish refusenik emigration from the Soviet Union at that time allowed approximately 150,000 Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a further 400,000 departed, with more than 80% heading to Israel and the remainder mostly to Germany and the US – several members of my own family among them. In 2014, the number of Ukrainian Jews immigrating to Israel jumped by 190% in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine. Jewish emigration from Russia also spiked and the numbers coming to Israel from both countries stabilised at this higher level in the eight years leading up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With another war now raging in the Middle East, some of those displaced by the hostilities in Ukraine have had to flee twice over. Among them are more than sixty children from the Alumim children’s home near Zhytomyr in western Ukraine. Some are orphans from the surrounding towns and villages within the historic Pale of Settlement, others have parents who are unable to provide a stable home for them. On 24 February 2022, bombs began to fall around the home, which was located close to a Ukrainian air base. Its founders, Rabbi Zalman Bukiet and his wife Malki, had made advance preparations in case of a Russian attack and were able to quickly evacuate the children to the west of the country by bus. After a few days, when it became clear that the war would not reach a swift conclusion, they crossed the border into Romania and from there boarded a plane to Israel. The logistics of the transfer were complex as almost none of the children had passports. Some of their mothers and other community members joined the group until it numbered 170 people. “El Al Airlines wanted us to finalise the number of seats we needed, and the paperwork was an open question,” Rabbi Bukiet recalled. One child had been away visiting his home village when the war broke out and had to be driven to Romania by taxi for a fare ten times higher than the standard rate. Once in Israel, the group was hosted at the Nes Harim education centre in the Jerusalem Hills. “We came for a month and stayed for six,” Rabbi Bukiet said. But as the new school year came round, he needed to find a more permanent home for the children. The group moved to Ashkelon, a coastal town in southern Israel, and rented two accommodation buildings – one for girls and one for boys – as well as apartments for the 16 families that had come with them from Zhytomyr and a home for the rabbi and his own family. “And so Ashkelon became home. The kids learned Hebrew, gained Israeli friends and integrated into the local community. The mothers took jobs and learned to navigate life in Israel. And we all got used to the new normal,” Rabbi Bukiet said. He and Malki arranged visits for a family member from Ukraine for each child, along with outings and activities. With the next school year due to begin, the group decided to stay another year in Ashkelon. Until history repeated itself. On 7 October the sirens once again blared at six am, just as they had in Zhytomyr 18 months or so earlier. Once again, the sound of gunfire and explosions reverberated around them. Rabbi Bukiet and his own family ran to a shelter but were unable to reach the children’s dormitories until midday. By the afternoon, the constant sirens had eased the he and Malki were able to gather the children together in a larger shelter. That night they made plans to relocate again, further north into Israel. Today the inhabitants of the children’s home are based in the Hasidic village of Kfar Chabad, not knowing how long they will stay. Safe for now, their future is uncertain once again. The full story of the Alumim children's home can be found here: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/6186434/jewish/How-Our-Childrens-Home-in-Ukraine-Was-Uprooted-Again-by-War-in-Israel.htm

0 Comments

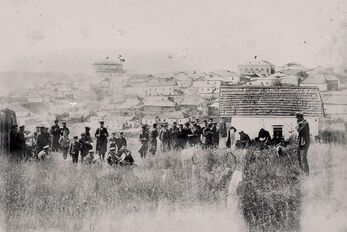

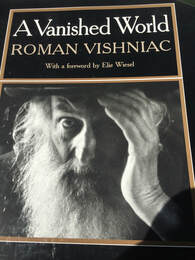

Ukraine doesn’t rank high on the holiday bucket list for most of us right now. But thousands of Hassidic Jews have ignored warnings about travelling to a war zone and flocked to the small town of Uman, some three hours south of Kyiv, for an annual new year pilgrimage. They came to worship at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov who was buried in Uman in 1810. Not all are religious Jews, for according to tradition, the rabbi promised to intercede on behalf of anybody praying at his grave on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. This year around 35,000 pilgrims arrived in Uman (up from the 23,000 who visited last year) in spite of warnings from the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities not to travel because of the risk of Russian air attacks and insufficient bomb shelters for the influx of visitors. Some brought young children with them, believing that a child who visits the grave site before the age of seven will grow up to be without sin. A small number of pilgrims have even been known to bring newborn babies to be circumcised in Uman, in spite of a lack of medical facilities for the procedure in Ukraine. Visitor numbers are only slightly down on the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, even though Uman has been targeted on several occasions. In April more than 20 missiles struck the town killing 24 people including several children in a residential district. It last came under Russian missile attack in June. The front line lies around 200 miles to the south. “It is very dangerous. People need to know that they are putting themselves at risk. Too much Jewish blood has already been spilled in Europe. How can you take such a risk?” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this month. With Ukrainian airspace closed, the journey to Uman is long, costly and uncomfortable, involving a flight to Poland, trains, minivan taxis and an inevitable long wait at the border. But the pilgrims remain undeterred in spite of the danger, expense and logistics of holidaying in a war zone. Some are firm in the belief that their Rabbi will protect them from beyond the grave; others just come to party and have a good time. Most come from Israel and spend up to a week in Uman around Rosh Hashanah. Although women are allowed on the pilgrimage, the vast majority of the visitors are men. The annual Jewish gathering has become the town’s major source of income, with pilgrims charged a $200 fee to visit. In recent years, the rabbi’s grave has been renovated with funds donated by Jewish tycoons from around the world. Hotels and hostels have popped up and locals have carried out house renovations to provide accommodation priced at hundreds of dollars a night. Those who can’t afford the exorbitant room prices pitch tents in courtyards or vacant lots. A whole hospitality industry has built up around the pilgrims, offering kosher food and drink at vastly inflated prices, using Hebrew signage and accepting payment in dollars or Israeli shekels. Most of the business owners are Israelis. Dozens of Israeli families moved to Uman in the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The annual influx of bearded, black-robed, skull-capped men makes quite an impact in this quiet town. While the visitors provide Uman with much-needed cash, relations between the pilgrims and the townsfolk are not always harmonious. Locals complain about the loud music, drunkenness, fighting and excessive litter. They resent the police cordons and checkpoints that prevent them from going about their daily business; and they question how the authorities are spending the money collected from the pilgrims, citing widespread corruption. Imagine a massive rave – albeit a religious one – taking over the streets of a small, unexceptional town and you start to get the picture. The Hassidic music blasting from speakers in the streets is imbued with a techno twist. Alcohol and drugs are much in evidence, as is prostitution. It’s hard to put a number on the percentage who come to celebrate and party, not just to pray. There’s a heavy security presence, even in peacetime, but it was stepped up this year in light of the added dangers of war. Police numbers have increased since 2010, when a young Israeli was stabbed in a brawl and ten pilgrims were deported after violent clashes broke out. Violence in Uman is nothing new. In 1941, under German occupation, the Nazis murdered 17,000 Jews here and destroyed the Jewish cemetery, including the grave of Rabbi Nachman, which was later located and moved before the area was redeveloped for housing. The original burial site was close to a mass grave for victims of another Jewish massacre, one that took place in 1768 as part of the Haidamak uprisings. The Uman pilgrimage began shortly after the rabbi’s death in the early 19th century and attracted hundreds of Hassidic Jews from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland until the Russian Revolution of 1917 closed the borders. The photo below dates from this period. In spite of the Communist regime’s clampdown on religious practice, a trickle of pilgrims continued to visit the grave site, including some Soviet Jews who made the journey in secret and were exiled to Siberia as a consequence. From the 1960s, small numbers of American and Israeli Jews travelled to Uman either legally or clandestinely. In the late 1980s, travel to the Soviet Union became easier and the number of pilgrims began to grow. Around 2,000 made the journey to Uman in 1990, rising to 25,000 by 2018.  I recently received as a gift a stunning book of photographs by the Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac. The photos were taken in the shtetls of eastern Europe in the 1930s, just before those communities were wiped out forever. A Vanished World was published in New York in 1983. It is difficult to get your hands on a copy of it now, but the photographs it contains serve as an important historical document. Vishniac was born in Russia, but was living in Germany in the 1930s. He took the photographs between 1934 and 1939, when the Nazis had already taken power, and when anyone with a camera was at risk of being branded a spy – and in communities where observant Jews did not want to be photographed for religious reasons. But he had the foresight to see what few others could possibly imagine, that the Nazis would systematically wipe out the shtetls and Jewish communities that had existed and maintained the same way of life for hundreds of years. He made it his mission to not let their inhabitants, along with their occupations and preoccupations, be forgotten. “I felt that the world was about to be cast into the mad shadow of Nazism and that the outcome would be the annihilation of a people who had no spokesman to record their plight. I knew it was my task to make certain that this vanished world did not totally disappear”, he says in his commentary on the photos. Vishniac used a hidden camera, at a time when photography was in its infancy and equipment was bulky and unsophisticated. He put himself at great risk, and was thrown into prison for a time, but still he persisted in his mission, constantly running the risk of being stopped by informers or arrested by the Gestapo. He managed to take around 16,000 photographs, although all but 2,000 were confiscated and, presumably, destroyed. He chose to include around 200 in this book, the images that he considered the most representative. He travelled from country to country, taking in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania, from province to province, village to village. He captured images of slums and markets, street scenes and school houses, from the wrinkled faces of old men and careworn mothers to pale religious scholars and hungry, wild-eyed children. The images are far from anonymous. Vishniac got to know the people he photographed, he often availed of their hospitality and spent time working and living among them. He slept in a basement that was home to 26 families, sharing a bed with three other men. “I could barely breathe, Little children cried; I learned about the heroic endurance of my brethren,” he wrote. He spent a month working as a porter in Warsaw, pulling heavy loads in a handcart, in one of the very few occupations still open to Jews during the Jewish boycott in the late 1930s, which forced tens of thousands of Jewish employees out of their workplaces. It was cheaper to have a Jew pulling a cart than a horse, for the horse had to be fed before it would work, while Jews were forced to carry the goods first and eat later, only once they had been paid. As one reviewer, the American photographer and museum curator Edward Steichen, wrote, “Vishniac took with him on this self-imposed assignment – besides this or that kind of camera or film – a rare depth of understanding and a native son’s warmth and love for his people. The resulting photographs are among photography’s finest documents of a time and place”. Vishniac emigrated to New York in 1940 and became an acclaimed photographer and professor of biology and the humanities. His only son Wolf died in Antarctica while leading a scientific expedition, and his grandson Obie died at the age of just 10. The book is dedicated to them, as well as to Vishniac’s grandfather. He writes: “Through my personal grief, I see in my mind’s eye the faces of six million of my people, innocents who were brutally murdered by order of a warped human being. The entire world, even the Jews living in the safety of other nations, including the United States, stood by and did nothing to stop the slaughter. The memory of those swept away must serve to protect future generations from genocide. It is a vanished but not vanquished world, captured here in images made with hidden cameras, that I dedicate to my grandfather, my son and my grandson."  I was interested to read this week of the death of the Viznitzer Rebbe Mordechai Hager in New York at the grand age of 95, for I have a distant (although unconfirmed) connection to the Viznitzer rabbis. My great-great-great grandfather, Akiva Hager (pictured), was in some way related to the Hager rabbis of Viznitz, but even back in the 19th century, apparently no-one in the family could actually put their finger on the blood link that connected them to the esteemed rabbis. Nevertheless, the family was always aware of how distinguished the Hager name was and sharing the name meant that they commanded respect among the Jewish community in which they lived. The Viznitzer rabbis were one of the most famous and revered dynasties in Hassidic Judaism. The sect was founded in the mid-1800s by Rabbi Menachem Mendl Hager in Viznitz (Vyzhnytsia in Ukrainian), a village in the foothills of the Carpathian mountains now in southwest Ukraine. Mordechai Hager was born in 1922, in Oradea, Romania, known in Yiddish as Grosswardein. His father, Chaim Meir Hager, was the fourth grand rabbi of Viznitz, and moved the dynasty to Grosswardein during the First World War. The Viznitz rabbinical dynasty today has congregations in Israel, London and Montreal as well as New York City and state. Despite sharing the revered family name of Hager, my forefathers made the decision to drop the name in order to save my great-great-great grandfather Akiva from conscription. At that time, in the mid-19th century, Jews were a particular target of Tsar Nicholas I’s military recruiting officers, known in Yiddish as ‘happers’. The happers were supposed to take boys aged between 12 and 18, but often recruited (some would say kidnapped) younger children, some as young as eight or nine, to fulfil their quotas, bundling them into uniforms meant for youths twice their age. Military service lasted a full 25 years, but most did not survive that long. It took only days for the Jewishness of the new recruits to be squeezed out of them like water from a sponge. They were barred from following the kosher laws or keeping the Sabbath, or even from speaking Yiddish. Any boy who insisted on holding fast to the dietary laws – refusing to eat pork or soup made with lard – was beaten with a rod or deprived of drinking water. And however firm their Jewish resolve, the boys were unable to avoid marching or performing drills on the Sabbath. At the end of a ten hour march, having eaten nothing but dry bread, the young recruits would arrive exhausted at their destination and were often forced to kneel until they agreed to convert to the Orthodox Christian faith. If they continued to refuse, they had to kneel all night. Some boys would take their own lives rather than agree to convert. Others would be beaten and starved and died from fever or exposure before ever setting eyes on a battlefield. As well as changing Akiva’s name to avoid such a fate, his family refused to let him attend school or any other formal institution – it was well known that Jewish boys who tried to enrol in a Russian ‘shkole’ could find themselves offered up as recruits for the army. So Akiva avoided conscription but never learned to read or write. By the time Akiva was in his late teens, Tsar Nicholas upped the conscription rate still further as Russia headed towards the Crimean War. Wealthier families tried to bribe the conscription officers to stop them from taking their sons, but there was no guarantee of success. Akiva’s family didn’t have the money to pay a bribe and instead they sent him to the dentist to have all his teeth extracted, a procedure that must have been horribly painful in the days before anaesthetic, and altered his appearance for life. But the loss of his teeth was successful in keeping Akiva out of the army, and had that not been the case, I probably wouldn’t be here today to tell his story.  I, and many others with a similar background, owe a great debt to a young Ukrainian called Vitaliy Buryak, who is single-handedly documenting the shtetls of Ukraine on his website (link below). He has recently put together a page on Makarov, the home of my great-grandfather Meyer Unikow. This week I have been providing him with some information for the site, some of which he will pass on to the museum in Makarov, where the new curator is putting together an exhibition on the town’s Jewish community. The town is about 40 miles west of Kiev, with a population of around 12,000. In 1897, when my great-grandfather was 25 years old, almost 4,000 Jews lived in Makarov, about three-quarters of the town’s population. Today there are 10, all of them incomers after World War II. My great-grandfather (on my grandmother’s paternal side) grew up at the court of the Twersky Rabbis of Makarov, a famous Hassidic dynasty that originated in Chernobyl, a town now notorious for an entirely different reason. Rebbe Menachem Nachum Twersky (b.1805, Chernobyl – d. 1852, Makarov), the first son of the second Chernobyl rebbe, founded the Makarov branch of the dynasty. The rabbis that my family would have lived, studied, prayed and eaten with are Rebbe Yaakov Itshak Twersky (1828-1892, Makarov), Rebbe Moshe Mordechai Twersky (b. 1843, Makarov – d.1920 Berdichev) and Rebbe Yeshaya Twersky (b. 1861, Makarov – d.1919, Kiev). Rebbe Yaakov Itshak was a very influential rabbi, respected by the community. My great-great grandfather (on my grandmother’s maternal side) Berl Shnier was a devoted follower of his, despite living a day’s journey away in the town of Pavoloch. He would consult the Makarover rabbi on all important family matters, and usually spent Shabbat at the Twersky court. This is how he came to arrange the marriage of his daughter to the son of one of the Rabbi’s right-hand men and tutor to his sons – my great-great grandfather Velvl Unikow. Rebbe Moshe Mordechai Twersky was apparently famous for the power of his prayers, making them unforgettable for those who heard them. His son, Rebbe Tsvi Arye, who was known as a healer and miracle-worker, moved the court to the larger town of Berdichev – considered the capital of the Jewish Pale – after his father’s death. Makarov’s Jewish population was decimated during the Civil War of 1917-21, in particular in the summer of 1919 when pogroms by a faction led by the Cossack leader Sokolovsky and another led by Matviyenko slaughtered 20 Jews and prompted the majority of the Jewish population to flee. Of those who remained, around half were killed by a further pogrom carried out by the White Army under General Denikin. Most of those who fled never returned to Makarov and by 1926 the town’s Jewish population had been slashed to under 600. Vitaliy’s website recounts events described in some of the memoirs written about the pogroms by those who witnessed them. The details are truly horrific. During World War II, Makarov was occupied by the Nazis from July 1941-November 1943. In the autumn of 1941, up to 100 Jews were shot, amid several other mass shootings of between 7 and 30 members of the Jewish community at a time. Their belongings were sold to the local population. I visited Makarov with my father in 2005. The Twersky court was destroyed by the Nazis and nobody in the town knows exactly where it stood. The place where the main synagogue was located is now a rubble-strewn patch of wasteland close to the large, Soviet-style town square. The old Jewish cemetery has been destroyed. The graves of the Twersky rabbis Moshe Mordechai and Tsvi Arye were safeguarded and their remains reside in the vast Jewish cemetery in Berdichev. Thanks to money sent from abroad, their graves are topped with newly hewn gravestones of slate and marble and housed in a small, painted mausoleum. More information is available at http://jewua.org/makarov/  It’s amazing what Facebook can throw up. The other day this photo appeared in my news feed, showing the grave of Vevrik Rabinovich (1864-1939), the brother of the great Jewish storyteller and creator of Fiddler on the Roof, Sholem Aleichem. In the background is the burial chamber of Shlomo BenZion Twersky (1870-1939) of the Chernobyl Rabbinical dynasty. The picture was taken in the Kurenevka Jewish cemetery in Kiev. I have a connection to both of these men. I have been led to believe that Sholem Aleichem and his brother were the nephews of my great-great-great grandfather, Menachem Mendl Rabinovich – his sister’s children. Her name was Chaya Esther Rabinovich. It confuses me that these siblings have the same surname even after Chaya Esther’s marriage, to Menachem Nukhem Rabinovich. Perhaps Chaya Esther married a member of her own family, or perhaps my information is incorrect. Sholem Aleichem was most famous for his short stories featuring Tevye the dairyman, which became the basis for the musical and subsequent film of Fiddler. Aleichem’s first story was published in 1883, when he was 23 years old, and he went on to write over 40 volumes, novels, stories and plays. He also performed his stories at packed public buildings across the Jewish lands of present-day Ukraine. Sholem Aleichem often spent his holidays at a dacha in the countryside about an hour from Kiev. One summer’s day, he was lounging with a book when a woman of almost exactly the same age as him passed carrying bowls of soup. “That smells good!” he called out. Later, she returned and offered him some of her soup. That lady was Pessy Shnier, nee Rabinovich, my great-great grandmother. The two of them chatted for hours and worked out how they were related. If any of Sholem Aleichem’s descendants come across this article, I’d be delighted if they could get in touch, and perhaps we can try to clear up any confusion about how we may be related! The other grave in the photo is that of Rabbi Shlomo BenZion Twersky. The Twerksys were a Hassidic Rabbinical dynasty founded by Rabbi Menachem Nachum Twersky (1730-1787), a disciple of the founder of Hassidism, the Baal Shem Tov. My family has a strong connection to another of the Twersky Grand Rabbis – Rabbi David, or Reb Dovidl, Twersky of Talne (1808-1882). Another of my great-great-great grandfathers, this time on my grandmother’s paternal side, was Velvl Shapira – known as Velvele Tallner – Reb Dovidl’s chief advisor. Reb Dovidl took Velvele Tallner with him when he left his home town of Vasilkov in 1854 to become the great Rabbi of Talne. Reb Dovidl was also the subject of a popular Jewish folk song: Reb Dovidl Reb Dovidl der Vasilkover, voynt shoyn yetst in Talne, which my father was taught to sing as a child. It’s still popular today as a YouTube search will testify. Here’s just one of the many performances available.  I recently came across some information about the town of Skvira, close to my grandmother’s ancestral home in Pavolitch, on a Ukrainian website that is documenting the region’s old shtetls. Skvira is around 20 miles from Pavolitch, and when my father and I visited the area in 2005, we were given a tour of the shiny new synagogue there, built the previous year. The ancient town of Skvira was destroyed at the end of the 16th century, but was gradually rebuilt and by the mid-18th century, it was documented as a village, leased to a Jewish tenant. According to a census of 1765, there were 124 houses in Skvira, 51 of which belonged to Jews. By 1897, just before my grandmother was born, almost 9,000 Jews lived in the town – half the population. By this time, Skvira had seven synagogues, seven Jewish prayer houses, a parish school and a hospital. Skvira was home to the court of a branch of the famous Twersky Hassidic dynasty, founded by Rabbi Yitzchak of Skvira (1812-1885). The Twersky court gathered thousands of Hassidim for high holidays and its dynasty still exists today, most notably in New Square (Novy Skvir), in Rockland County, New York. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, many of its followers returned to Skvira to rebuild the synagogue and the Tzaddik’s court. The court housed a yeshiva, or Rabbinical school, where my great-uncle Naftula was a student. My family were followers of another branch of the Twersky dynasty, in Makarov. My great-grandfather grew up at the Rabbinical court there, his own grandfather having been an advisor to the famous Reb Dovidl Twersky of Talna. Skvira suffered a wave of pogroms during the civil war (1917-20), during which more than 600 Jews were killed and a further 400 injured. The pogroms were led by different ‘banda’ (as my grandmother called the groups of armed thugs roaming the area, each with allegiance to a different leader). Three of the pogroms, in February 1919 and two in September the same year, were organised by Ukrainian independence fighters under Symon Petlyura. Others were led by the Red Army, the White Army under General Denikin, and Ukrainian People’s Army troops. Hundreds of women were raped, houses burnt to the ground, Jewish property seized and destroyed or sold. The town was left in ruins. The pogroms were followed by a typhus epidemic, which killed up to 30 people a day. Naftula had been in Skvira at the time of some of the worst pogroms, but thankfully was unharmed. The town’s Jewish population numbered some 15,000 before the pogroms, and just 10,000 afterwards. Many then fled to Kiev, Odessa or nearby Belaya Tserkov, or emigrated. By the start of World War II, the Jewish population had been whittled down to 2,243, although this still made it one of the biggest Jewish communities in Ukraine at the time. Like everywhere else in the region, Skvira suffered terrible atrocities during World War II. In September 1941, around 850 Jews were gathered and shot in three pits in the Jewish cemetery. Two further mass killings (or ‘actions’) took place, in October and November of the same year. The total number of Jewish deaths in the town during the Nazi occupation was 1,230. Skvira was liberated by the Soviet Red Army in December 1943. The post-war Jewish population numbered about 1,000, many of whom had escaped to the Urals or Central Asia during the war years. In 2009, shortly after my visit, only around 120 Jews remained. See http://jewua.org/skvira/ for more information The death of Rabbi Mendel Deitsch last week resonated through the Jewish community and throws up parallels with the past. The Rabbi was beaten up in the Ukrainian city of Zhitomir at in October last year, at Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. He was robbed of his money and mobile phone at the city’s train station, suffering multiple head injuries and brain trauma. He was not discovered until hours later and was airlifted to hospital in Israel, where he remained unconscious until his death on 14 April.

Ukraine continues to suffer high levels of anti-Semitic crime, despite the appointment of a Jewish prime minister, Volodymyr Groysman, last year. Incidents include the desecration of Holocaust memorials and Jewish cemeteries with Swastikas and Nazi slogans, and an attack on a former synagogue in Uzhgorod, western Ukraine, which was daubed with red paint and anti-Semitic pamphlets. Most shockingly, the grave of one of Judaism’s most revered figures, Rabbi Nachman of Breslav in Uman was vandalised on the eve of Hannukah and adorned with a pig’s head. In Zhitomir, the scene of Rabbi Deitsch’s attack, the mass graves of holocaust victims were dug up earlier this year by thieves looking for gold teeth. In early 1919, Zhitomir was the scene of one of the worst anti-Semitic attacks of Russia’s Civil War. Just like the assault on Rabbi Deitsch almost 100 years later, the initial attacks took place at the city’s train station, where followers of Symon Petlyura, one of the leaders of Ukraine’s fight for independence and a vicious anti-Semite, carried out a massacre, killing 17 Jews, many of them old men on their way home from synagogue. But it didn’t stop there. Local peasants started a rumour that spread around the whole of Zhitomir in a matter of hours. They said that during the recent brief period that the Red Army had occupied the city, the Jews who had taken charge of the civil authorities had put to death nearly two thousand Christians. Who were these condemned men? Why and where were they killed? Nobody knew the answer to these questions – because there had been no mass execution. The rumours were pure fantasy, aimed at inciting hatred against the Jews. Thankfully the stories of Christian carnage provided a warning and when the pogrom began, all those who were able had already scattered to the wind or sought refuge with Ukrainian friends or neighbours. The only Jews left were the elderly or infirm, pregnant women and nursing mothers. But the slaughter went ahead regardless. An old man on his way to synagogue with his prayer shawl over his arm was the first to die. He was propped against a tree and shot. But the bullet didn’t kill him. The old man dragged himself towards the synagogue on his hands and knees, but collapsed and died in the street just yards from the door, while Petlyura’s men stood and watched. Witnesses spoke of seeing people having their eyes gouged out, their clothes torn off and the skin of their shoulders engraved by knife-blade with the badge of rank of their killer. The pogrom lasted for five days. Over three hundred Jews were killed. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed