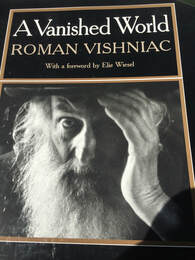

I recently received as a gift a stunning book of photographs by the Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac. The photos were taken in the shtetls of eastern Europe in the 1930s, just before those communities were wiped out forever. A Vanished World was published in New York in 1983. It is difficult to get your hands on a copy of it now, but the photographs it contains serve as an important historical document. Vishniac was born in Russia, but was living in Germany in the 1930s. He took the photographs between 1934 and 1939, when the Nazis had already taken power, and when anyone with a camera was at risk of being branded a spy – and in communities where observant Jews did not want to be photographed for religious reasons. But he had the foresight to see what few others could possibly imagine, that the Nazis would systematically wipe out the shtetls and Jewish communities that had existed and maintained the same way of life for hundreds of years. He made it his mission to not let their inhabitants, along with their occupations and preoccupations, be forgotten. “I felt that the world was about to be cast into the mad shadow of Nazism and that the outcome would be the annihilation of a people who had no spokesman to record their plight. I knew it was my task to make certain that this vanished world did not totally disappear”, he says in his commentary on the photos. Vishniac used a hidden camera, at a time when photography was in its infancy and equipment was bulky and unsophisticated. He put himself at great risk, and was thrown into prison for a time, but still he persisted in his mission, constantly running the risk of being stopped by informers or arrested by the Gestapo. He managed to take around 16,000 photographs, although all but 2,000 were confiscated and, presumably, destroyed. He chose to include around 200 in this book, the images that he considered the most representative. He travelled from country to country, taking in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania, from province to province, village to village. He captured images of slums and markets, street scenes and school houses, from the wrinkled faces of old men and careworn mothers to pale religious scholars and hungry, wild-eyed children. The images are far from anonymous. Vishniac got to know the people he photographed, he often availed of their hospitality and spent time working and living among them. He slept in a basement that was home to 26 families, sharing a bed with three other men. “I could barely breathe, Little children cried; I learned about the heroic endurance of my brethren,” he wrote. He spent a month working as a porter in Warsaw, pulling heavy loads in a handcart, in one of the very few occupations still open to Jews during the Jewish boycott in the late 1930s, which forced tens of thousands of Jewish employees out of their workplaces. It was cheaper to have a Jew pulling a cart than a horse, for the horse had to be fed before it would work, while Jews were forced to carry the goods first and eat later, only once they had been paid. As one reviewer, the American photographer and museum curator Edward Steichen, wrote, “Vishniac took with him on this self-imposed assignment – besides this or that kind of camera or film – a rare depth of understanding and a native son’s warmth and love for his people. The resulting photographs are among photography’s finest documents of a time and place”. Vishniac emigrated to New York in 1940 and became an acclaimed photographer and professor of biology and the humanities. His only son Wolf died in Antarctica while leading a scientific expedition, and his grandson Obie died at the age of just 10. The book is dedicated to them, as well as to Vishniac’s grandfather. He writes: “Through my personal grief, I see in my mind’s eye the faces of six million of my people, innocents who were brutally murdered by order of a warped human being. The entire world, even the Jews living in the safety of other nations, including the United States, stood by and did nothing to stop the slaughter. The memory of those swept away must serve to protect future generations from genocide. It is a vanished but not vanquished world, captured here in images made with hidden cameras, that I dedicate to my grandfather, my son and my grandson."

2 Comments

Linda Lawlor

3/4/2019 01:04:24 pm

Very moving - are there any links to the photos ?

Reply

9/4/2019 08:02:52 am

Yes, you can find them by googling Roman Vishniac photos, or follow this link. They are well worth a look.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed