Ukraine on 26 November marked the 90th anniversary of the Holodomor – the famine of 1932-33 in which millions of Ukrainians died. Since 2006, the country has recognised the Holodomor as a deliberate act of genocide against the Ukrainian people, perpetrated by the Soviet authorities under Joseph Stalin. The anniversary falls as Russia is once again using food as a weapon of war, both against the Ukrainian people and the rest of the world, and with Ukrainians again facing what may be perceived as genocide at the hands of a Russian regime that denies Ukraine’s right to statehood. “Ninety years after the Holodomor genocide committed on the territory of Ukraine, Russia is committing a new genocide – war. The eternal enemy is again trying to “denationalise” and suppress us so as not to let us out of its influence and prevent the strengthening of Ukrainian statehood. The methods of the latest Putin regime differ little from Stalin’s: murder, terror with hunger and cold, intimidation, and deportation,” Kyiv’s Holodomor museum said on 16 November. The term Holodomor derives from the Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor). Between 3.5 million and 7 million people are estimated to have died in Ukraine’s grain producing regions during the Holodomor. The famine peaked in the summer of 1933, when the daily death toll from starvation is estimated at around 28,000. During this period, the Soviet Union exported 4.3 million tonnes of grain from Ukraine to earn hard currency to pay for its industrialisation drive. The famine came about as a result of Stalin’s policy to collectivise agriculture, forcing those who lived and worked on the land to give up their farm holdings and personal possessions to join the new collective farms. Collectivisation faced mass opposition in many parts of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine, and led to lower production and food shortages. In November 1932, Stalin dispatched agents to seize grain and livestock from newly collectivised Ukrainian farms, including the seed grain needed to plant crops the following year. While other grain-producing regions of the Soviet Union also suffered mass hunger as a result of collectivisation, the policies enacted in Ukraine were far more brutal than elsewhere, with whole villages and towns blacklisted and prevented from receiving food, as Stalin sought to stifle rebellions and armed uprisings by Ukrainian resistance movements. Yale University historian Timothy Snyder has referred to the mass starvation that followed as “clearly premeditated mass murder”. The harsh reprisals against Ukrainians included a campaign of repression and persecution against Ukrainian culture, religious leaders and anyone accused of Ukrainian nationalism. The Soviet authorities denied the existence of famine, prevented travel to the regions affected and suppressed reports of it, refusing offers of assistance from the Red Cross and other humanitarian organisations once news of the tragedy leaked out. The parallels between Stalin’s repression of Ukraine in the early 1930s and Russian president Vladimir Putin’s actions 90 years later are stark. Russia’s targeting of grain storage facilities and its blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea exports have sparked accusations that Moscow is using food as a weapon of war. And repeated waves of attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure are cutting off electricity and water supplies with the aim of breaking the resolve of the Ukrainian people, just as the withdrawal of food supplies did during the Holodomor. "On the 90th anniversary of the 1932-1933 Holodomor in Ukraine, Russia's genocidal war of aggression pursues the same goal as during the 1932-1933 genocide: the elimination of the Ukrainian nation and its statehood," Ukraine's foreign ministry said in a statement. And Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky said in a video posted on social media, “Once they wanted to destroy us with hunger, now – with darkness and cold…. We cannot be broken.” Several European leaders – including from Belgium, Lithuania and Poland – travelled to Ukraine for the anniversary to pledge their support for the country. Other nations, including Germany and Ireland – which suffered its own devastating famine in the 19th century – are joining Ukraine in recognising the Holodomor as a genocide on the Ukrainian people. And Michael Carpenter, the US ambassador to the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, addressed its permanent council in Vienna with a damning statement: “The men, women, and children who lost their lives during this famine were the victims of the brutal policies and deliberate acts of the regime of Joseph Stalin. This month, as we commemorate those whose lives were taken, let us also recommit ourselves to the constant work of preventing such tragedies in the future and lifting up those suffering under the yoke of tyranny today. “It is especially important this year to remember that the word “Holodomor” means “death by hunger.” Putin’s regime is demonstrating its brutality in Ukraine by conducting attacks across Ukraine’s agriculture sector and by seizing Ukraine’s grain, effectively using food as a weapon of war.” Ukrainians typically mark the anniversary, which falls on the fourth Saturday of November, by placing candles in their windows. Today they need those candles to light their homes.

0 Comments

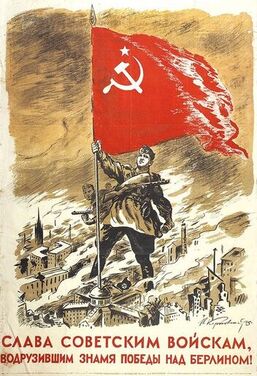

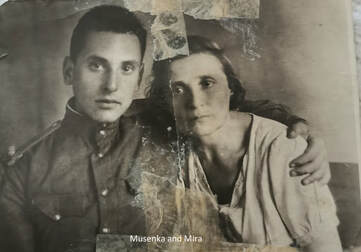

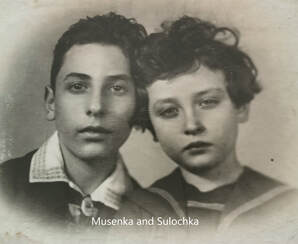

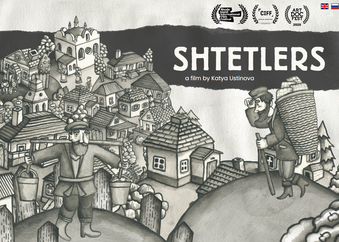

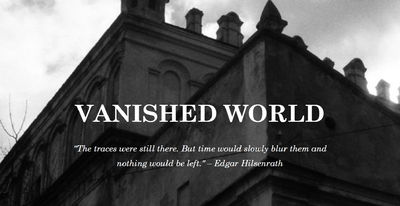

Victory Day, on 9 May, is the most solemn and serious of national celebrations in Russia. On this date thirty years ago, I was in the southern Russian city of Voronezh. It was a beautiful, sunny day, the warmest of the year so far after a long, bleak winter. The main street was closed to traffic and it seemed the whole population of the city was outdoors. But the glorious holiday weather didn’t prompt people to shed layers of clothing and relax with picnics and drinks in the city’s parks as they might have elsewhere. Instead, families walked, silent and sombre, towards the war memorial to lay flowers, three or four generations together. The older men wore rows of medals with multi-coloured ribbons attached to their jackets. Many were dressed in military uniform. The women were togged up in their Sunday best. Children were primped and preened with oversize bows for the girls and buckles and braces for the boys. Although the holiday celebrated the victory of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is known – there was no sense of jubilation. The Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the victory and the war took a terrible toll. An estimated 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Every family lost a son, a brother, a father, an uncle or a cousin. The pomp and ceremony of today’s Victory Day parade in Moscow add some glitz and glamour that didn’t exist in the immediate post-Soviet era. And of course, the war in Ukraine adds poignance to the occasion. It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin in his Victory Day speech linked the current conflict with the triumph over Nazi Germany. Time and again, he has drawn parallels between the two wars, starting with his bizarre notion of the need for Russia to rid Ukraine of Nazis. Given the Jewish origins of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, the Nazi tag has struggled to stick. But Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comparison of Zelensky with Adolf Hitler, in an attempt to legitimise Russia’s goal of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, took the analogy up a notch. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst anti-Semites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood – statements that typify the distortion of history that underpin Russia’s war with Ukraine. The question of Hitler’s Jewish identity is nothing new – and remains unproven. The issue centres on Hitler’s father, born in Graz, Austria, in 1837 to an unmarried mother. Speculation over who the child’s father was has continued for decades, fuelled by the fact that following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the records of his grandmother’s community to be destroyed. A memoir by Hans Frank, head of Poland’s Nazi government during the war, claimed that the son of Hitler’s half-brother tried to blackmail the Nazi dictator, threatening to expose his Jewish roots. Following worldwide outrage over Lavrov’s comments, and in particular heated condemnation from Israel, the Russian president was forced to issue a rare apology to his Israeli counterpart, Naftali Bennett, rather than risk alienating a country that has been more supportive than most. Israel has been an ally of Russia since the end of the Soviet Union – based in part on both countries’ military interests in Syria and the substantial Russian-Jewish population in Israel – and has faced criticism for failing to join Western sanctions. Israeli foreign minister Yair Lapid said Lavrov’s comments “crossed a line” and condemned his claims as inexcusable and historically erroneous, while Dani Dayan, head of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem, denounced them as “absurd, delusional, dangerous and deserving of condemnation”. Russia’s foreign ministry hit back, accusing the Israeli government of supporting a neo-Nazi regime in Kyiv. Only time will tell if the war of words leads to firmer Israeli support for Ukraine. Russian TV host Vladimir Solovyov last week pushed the Nazi narrative further, clarifying a new definition of Nazism to explain the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. “Nazism doesn’t necessarily mean anti-Semitism, as the Americans keep concocting. It can be anti-Slavic, anti-Russian,” he said. To keep its phoney narrative alive, Russia will keep churning out the rhetoric on Nazism in the hope that if it repeats it often enough and loudly enough, more people will believe it. But the longer Putin’s Russia continues murdering Ukrainian citizens and bombarding Ukrainian cities, the more it resembles Hitler’s Nazi regime.  This month marks the 80th anniversary of the worst of the Nazis’ multitude of atrocities on Ukrainian soil, the massacre at Babi Yar on 29-30 September 1941, which began on the eve of Yom Kippur. The Babi Yar tragedy was largest open-air massacre during the so-called Holocaust by Bullets, when 33,771 people – according to meticulous record-keeping by the SS – mostly women, children and the elderly, were shot. In the months that followed, tens of thousands more people were murdered at Babi Yar, the overwhelming majority Jews, but also Roma, Ukrainian nationalists and Soviet prisoners of war. The killing came to a halt in 1943, with the Germans in retreat from the Soviet territory they had occupied. Berlin ordered that mass execution sites be excavated so the corpses could be burned, fearing that the Soviet Union would use them as evidence for propaganda purposes. Until its collapse in the 1990s, the Soviet Union suppressed memory of the Jewish genocide that had taken place on its soil. National policy was to erase differences among the victims of Nazism. This included ‘erasing’ the ravine itself by filling it with industrial waste and making way for what exists at the site today – a wide street lined on one side with apartment blocks, and a grassy park on the other, where children play and lovers meet. “Babi Yar is a symbol of the Soviet Union’s efforts to physically erase memory. They took the most tragic part of our history and tried to make it disappear. Thanks to an independent Ukraine, the policy was fully changed towards the memory of the Holocaust,” human rights activist and chairman of the Babi Yar Holocaust Memorial Center, Natan Sharansky, said last year at a ceremony to mark the anniversary of the massacre. The Memorial Center, established in 2016 to build a major new Holocaust museum in Kiev, is due to open its doors in 2026 but has already been the subject of considerable controversy. The disagreements stem largely from the appointment of the contentious Russian filmmaker Ilya Khrzhanovsky as artistic director and his plans for a virtual reality installation, deemed inappropriate by many and dubbed a “Holocaust Disneyland” by one former curator when he quit the project. Objections have also been raised about the role of some of the Center’s Russian Jewish billionaire funders and its location in the grounds of an old Jewish cemetery. But a number of research projects developed by the Center have yielded fascinating results. Last year a 3D model of the massacre site was created, led by former Scotland Yard investigator Martin Dean, who specialises in Nazi war crimes. By combining ground and aerial photography, maps, historical reports and witness testimonies, Dean was able to build an overall picture of a mass grave about 150 metres long, in which corpses were stacked in layers like sardines, and to pinpoint for the first time in three-quarters of a century exactly where it was located. Another recent research initiative is the Names Project, which has uncovered the identities of more than 900 of the victims of Babi Yar, whose fates had previously been unknown. Estimates of the total death toll at Babi Yar in 1941-43 range from 70,000 to 100,000. Apart from details of the September massacre, records of those killed were sporadic. The Names Project is attempting to collect data on all those murdered at Babi Yar and the researchers hope eventually to have a web page for each identified victim, complete with details of their life story and a picture. In partnership with the Memorial Center, Ukrainian director Sergei Loznitsa released a film this year to coincide with the 80th anniversary. Babi Yar.Context – a series of short documentaries – premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in July. Loznitsa was born close to Babi Yar but grew up in ignorance of what had happened there. His film is based on archival material using footage from the period, including newsreels, court trials and amateur films by German soldiers. It begins with Germany’s invasion of Ukraine in 1941 and concludes in March 1961 with the little-known Kurenivka mudslide – a disaster that resulted from the Soviet authorities’ attempts to erase memory of Babi Yar by filling the ravine with industrial waste. A decade later, heavy rain caused a dam securing a brick pulp dump to collapse, triggering a mudslide that released up to four metres of mud, water and human remains onto the streets. A recent report estimates that 1,500 people may have died as a result.  The Gulag was the largest network of forced labour camps ever created, spanning thousands of miles across the Soviet Union. Around 18 million prisoners, possibly more, were sent to the Gulag from 1930 to 1953 during the rule of Joseph Stalin, of whom up to three million died in the camps or as a result of their incarceration. As well as criminals, the Gulag became home to huge numbers of political prisoners. One of these was Yehuda Solomonovich Kaufman, the husband of my great-grandfather’s sister Miriam (Mira) – whose story I have been telling in my blog over the last few weeks – and grandfather to my cousin Irina (Ira), who has shared her family stories with me. Yehuda, originally from the town of Bobruisk in today’s Belarus, was arrested no less than three times before finally being sent to the Gulag in 1938. The first was in the 1920s when he was arrested as a Jewish nationalist because he gave private Hebrew lessons, in addition to his professional work as a surgeon. His next arrest came in 1931, this time because he corresponded with several members of his family (brothers, a nephew) who lived abroad. He was sent to prison, missing the birth of his daughter Sulamia as a result. In 1936-37 Yehuda’s nephew came to Kiev from overseas to visit, and after this he was arrested for a third time and sentenced to ten years in a labour camp in Krasnoyarsk region as an ‘enemy of the people’. Although conditions were harsh and his sentence was long, he was lucky in being able to work as a doctor, and like many inmates, he even had a ‘prison wife’. In 1949 Yehuda was finally permitted to return to Kiev. He left his prison wife to return to Mira, but no sooner had he set foot in his apartment for the first time in more than a decade than a group of state security agents arrived to arrest him once again. Rather than sending him back to the Gulag or to Siberia, he was exiled to the town of Zvenygorodka in Cherkasy province, central Ukraine, where he remained until his eventual release in 1956. Ira, who was born in 1952, recalls that as a little girl, her family told her that Grandpa was “in Paris”. But later she remembers visiting him in Zvenygorodka, in a room with a round table and a bed with springs, which she would use as a trampoline. Stalin died in 1953, and the Soviet reign of terror came to an end. But the truth of the labour camps, the mass deportations, executions and purges did not become public until Nikita Khrushchev cemented his place at the head of the Communist Party in the power struggle that followed Stalin’s death. Khrushchev’s so-called ‘secret speech’ to party officials in February 1956 denounced Stalin’s excesses and heralded a period of liberalisation, during which thousands of prisoners - including Yehuda – were set free and rehabilitated. Once he was finally back in Kiev after 18 years of separation from his family, Yehuda managed to return to his work as a surgeon and to put the experiences of the previous two decades behind him. He was a cheerful man, loved by friends, family and colleagues alike, who rejoiced in his family and in life in general. He built up a strong relationship with his daughter in spite of their long years apart, and doted on his grandchildren, giving them little presents every day. He even wrote stories about his childhood that he illustrated himself. He died in 1964. Although life improved for the people of the Soviet Union under the so-called ‘Khrushchev thaw’, the discrimination and anti-Semitism that hounded Jews first under the Tsars and then under the Communists did not go away. Religion had been abolished after the October Revolution of 1917, so Judaism was no longer considered a religion but a nationality, marked in Soviet passports on the personal details page under the notorious point number five: Национальность – Eврей (Nationality – Jewish). This opened Jews up to any and every form of discrimination and anti-Semitism, from being humiliated in the street and called a Yid, to being marked down in exams, denied a place at university, overlooked for a promotion. So Jews kept quiet about their ‘nationality’. Parents were afraid to teach their children Yiddish, to follow the traditions that their people had lived by for thousands of years, to celebrate the Jewish holidays, and so the Yiddish language and Jewish customs died out, although small pockets remained in smaller towns and rural communities. “We were a typical Soviet family,” my cousin Ira says. “Nothing remained of our Jewishness except our surname and an entry in our passport.” As a child, she and her sister Mila wanted to blend in, to be like everyone else. Their parents didn’t talk to them about their ‘nationality’, nor later did they ever discuss it with their children. It wasn’t until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 that Jews were permitted to emigrate, in a bid for freedom from discrimination. Hundreds of thousands left, mostly for Israel, but also for the United States and Germany, where Ira and her family now live.  The Soviet Union was not an easy place to live after World War II, and especially for Jews. Those who managed to survive the war by fleeing to Central Asia or the Urals and returned after the German retreat found their homes destroyed, their towns devastated, and their Jewish neighbours slaughtered. In Kiev, then in Soviet Ukraine, where several members of my family lived, nearly 34,000 Jews had been shot at the ravine known as Babi Yar on the edge of the city on 29-30 September 1941. But this was far from the only anti-Semitic atrocity committed by the Nazis in the city. My grandmother’s first cousin Baya was among a group of Jews herded to the banks of the river Dnieper and forced aboard a ship that was set alight. There were no survivors. And few rural Jews from the villages formerly known as shtetls survived the war either. In Pavoloch, my grandmother’s home town, on 5 September 1941 up to 1,500 Jews were shot beside a mass grave dug in the Jewish cemetery. The victims came from many outlying villages as well as Pavoloch, herded to the town for slaughter. The terrible event has become known as the Pavoloch Massacre and even featured in last year’s Amazon Prime series Hunters, which I found myself unable to watch. Several hundred thousand Jews fled to the eastern republics of the Soviet Union in 1941 as the Nazis approached. You can read some of their stories here. Many never went back to the towns they had left, unable to contemplate returning to places where such terrible devastation had taken place. Most, inevitably, would have lost family members or friends to the Nazis. It is hardly a surprise that a great number emigrated to Israel or the United States as soon as the possibility arose, while some remained in Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan, or elsewhere. But thousands of Jews did return to their homes in towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. In my last article I wrote about my grandmother’s aunt Miriam (Mira) and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka), who made it back from Central Asia to Kiev in December 1943. Mira’s son Moishe (Musenka) had been called up earlier the same year to a military academy in Turkmenistan, on the Afghan border, and did not come home with them. To continue their story, in 1944, Musenka was transferred to the front – to Poland. In preparation for his departure, he was moved to an army camp on the outskirts of Kiev, where his mother and sister were able to visit him. Later, from Poland, Musenka wrote that his regiment was preparing for a major offensive in Warsaw. He died on 16 October 1944, ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s final offensive to liberate the Polish capital. He was 18 years old. It was his sister Sulochka, rather than his mother Mira, who received the death notice sent by the Soviet military authorities. Sulochka was 13 and had become something of a tearaway – a fiercely independent girl who skipped lessons and swiped pastries from vendors at the old Jewish market. She hid the letter from her mother, knowing how deeply it would upset her. But Musenka had been a loyal son and always kept in touch regularly with his family. Mira descended into a panic after his letters stopped. She contacted the military authorities searching for information, but when a second copy of the death notice arrived, once again it was Sulochka who intercepted it. Mira wanted to die. She felt she couldn’t live without her precious only son and couldn’t bear not knowing what had happened to him. She returned to the ruins of her pre-war home in the hope that bricks from the half-demolished building would fall and kill her. She more or less ignored her living daughter, Sulochka, amid the pain she felt over her missing son. Her husband Yehuda – exiled to a labour camp near Krasnoyarsk – even wrote a letter to the war commissar Klim Voroshilov with a plea for help in finding any trace of Musenka. Many families waited years, decades even, for their menfolk to return from the war. Some were lucky; many were not. As time passed, the small glimmer of hope that her son was still alive and would one day come home gave Mira the strength to go on living. It was not until 1964, twenty years after Musenka’s death, and after Yehuda – finally liberated from the gulag – had also passed away, that Sulochka confessed to her mother that she had hidden the letters from the military authorities informing them that her brother had died in action. In the end, knowing the truth at last helped ease Mira’s distress. For all those years she had tormented herself with the thought that Musenka might have fallen into the hands of the Banderovtsy – the anti-Semitic Ukrainian nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, who allied with the Nazis and collaborated in the near-total destruction of Jewish life in Ukraine. The torture they inflicted on captured Red Army soldiers was notorious, and all the more so for those of Jewish descent. Mira spent her post-war years enveloped in grief over the loss of her beautiful boy – and yes, photographs testify that he was indeed beautiful. Her love for her daughter remained in the background; it clearly existed, but was rarely overtly demonstrated. Mira could be a stubborn and awkward character and she and Sulochka were often at loggerheads. But Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was 14 when Mira died in 1966, remembers her with warmth and affection. This story will be continued in my next article.  Soviet Jews that survived World War II by fleeing eastwards found a tough life waiting for them on their return home to towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. I wrote recently about the experiences of several Jewish families as refugees in Central Asia during the war, including my great-grandfather’s sister, Miriam (Mira) – you can read that article here. Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was born in Kiev after the war and lived there until the 1990s, has shared with me her family stories of life back in that city after the return from Central Asia. The family had lived before the war in the centre of Kiev, at 37 Pushkinskaya Street in a communal apartment – one room for each family, with shared cooking and washing facilities, as was typical of Soviet life during the era of Stalin and Khrushchev. Sometimes a family occupied just a section of a room, partitioned off with a curtain. On their return from Central Asia after the Nazi retreat in late 1943, Mira and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka) – Ira’s grandmother and mother – made their way from the station on foot – no public transport was running – through the ruins of the devastated city, to find out what had become of their home. They found the four walls still standing, but nothing more. The building was restored after the war and exists to this day. “Whenever I go back to Kiev, I always wander around the courtyard and look up at the balcony, as if I’m looking for my mother as a little girl,” Ira says. A quick Google search shows an attractive four-story building on a tree-lined street, next door to a “hip Israeli eatery” called Pita Kyiv and just down the road from the Estonian embassy. As Ira’s mother and grandmother stood weeping before their ruined home, a figure approached them – a woman they had been acquainted with before the war. Knowing what had happened to the Jews of Kiev at the end of September 1941, when 34,000 were shot at the ravine of Babi Yar on the edge of the city, the woman took pity on Mira and Sulochka. She led them back to her basement flat on Saksaganskaya Street, a mile or so away, and invited them to stay. There Mira recognised many of her own possessions and those of her neighbours, stolen when they had departed in haste during the evacuation of the city. Mira said nothing. She was grateful simply to have a roof over her head. Every day Mira returned to her building on Pushkinskaya in the hope of meeting the postman, desperate for news from her son Moishe (Musenka) in the army, and her husband Yehuda in the gulag. And she petitioned the authorities for a place to live for herself and her daughter. For once she was lucky, and was assigned a room in a communal apartment, but at the expense of another family, who were forced onto the street. The dispossessed family rushed at Mira and beat her in anger and despair at losing their home. With so much of the city destroyed and more evacuees returning by the day, the authorities would juggle the accommodation that was still standing, taking shelter from one family to give to another; a lottery of relief or desolation. The room was ten metres square, with no running water or sewerage. Later it became smaller still, with three meters reapportioned to create a corridor where a cooker was installed. But it was a roof over their heads and it was precious. In this room, nearly a decade later, Ira was born. How Mira found the means to live during this period, Ira doesn’t know. But she suspects it was Mira’s brother, Uncle Avrom, who came to their rescue, as he had during the evacuation of Kiev, finding transport for them and a place to live. Sulochka also told Ira about her cousin Beba. Ira says Beba’s real name was Volf. According to the family tree my grandmother and father drew up he was called Velvl, while his grandson – who now lives in Germany – refers to him as Vladimir. Such are the complications of Jewish genealogy! Cousin Beba was the only relative that did not turn against Mira when she became the wife of an Enemy of the People, after her husband was arrested in 1938 and sent to the gulag. One day Beba visited and saw that Sulochka had grown out of all her warm clothes, and in the dead of winter. He went to the crowded flea market where people bought and sold new and second-hand goods and found her a pair of warm boots. Mira continued to go back to the family’s old home on Pushkinskaya in the hope of seeing the postman and finding a letter from her son or husband. In 1944, Musenka wrote that he was being transferred to the front – to Poland – and that before his departure he would be based at a large camp on the outskirts of Kiev, by the Darnitsia train station across the river Dnieper. Mira and Sulochka were able to visit him there. Musenka was 18 years old and this was the last time his mother and sister ever set eyes on him. This story will be continued in my next article.  I have always been fascinated by Soviet history. I grew up at a time when the Iron Curtain was firmly drawn and what lay on the other side was beyond the bounds of my imagination. I have a dim recollection of the Moscow Olympics in 1980, and the tiny glimpses of the Soviet capital that the TV coverage allowed. But I was just a child then and my interest in the country’s history and politics were yet to emerge. I first travelled to the Soviet Union in 1989 on an organised tour shortly before embarking on my Russian degree at university. Flying low over the countryside on the approach to Moscow’s Sheremetyevo airport, I remember seeing mile after mile of forest. “Oh, so they have trees in the Soviet Union,” I naively thought to myself. (Duh! Of course there are trees, Russia’s covered in trees!). Until that moment, anything beyond the images I had seen of Red Square or the Olympic stadium felt utterly unknown. The whole country seemed such a closed world that I had no way of picturing it at all. I still feel the same way about North Korea today – it is sealed off so completely that I cannot imagine what it looks like. Back in 1989 I knew nothing of my family still living in Soviet Ukraine. I did not even know that I had cousins there, descendants of my great-grandfather’s siblings, who remained in Kiev after most of my grandmother’s family emigrated to the west in the early 20th century. Two years later I returned to the Soviet Union as a student, for a year-long immersion into Russian language and culture in the city of Voronezh. I arrived, part of a group of 30 students from British universities, just days after the failed Communist coup of August 1991 against Mikhail Gorbachev and his reform agenda of ‘glasnost’ and ‘perestroika’. Less than four months into my stay, the Soviet Union was dissolved, leaving its previously united republics in a state of chaos and disintegration. Some time after my arrival in Voronezh, a large envelope arrived in the post from my father. It contained a series of family trees, an envelope with an address in Kiev, and an old photograph of a mother with her two daughters. These are your cousins, the accompanying letter said, you can look on the family tree to see how you are related. You could try to get in touch. Dad had received the address and photo from my grandmother’s cousin Claire in Philadelphia. Claire had visited the Soviet Union back in the 1960s and made contact with another cousin, Sulamia, in Kiev – the photo now in my possession was taken during that visit, of Sulamia (Claire knew her as Sveta, her Soviet name) with her children Irina (Ira) and Miloslava (Mila). For some years after her visit, Claire had sent parcels of clothes and food to the family in Kiev, but eventually lost contact. I wrote a letter and introduced myself. Some weeks later I bought a train ticket to Kiev – well, not literally. It was impossible to buy a ticket from Voronezh to Kiev. First, I bought a ticket for the overnight train to Moscow, 500km to the north, which deposited me at the capital’s Paveletsky station at 6am the next day. From there I headed across town to Kievsky station and queued for a ticket to travel 900km southwest to Kiev, leaving that evening and arriving the following morning. It was a long and convoluted route to travel 600km due west. I don’t recall what I did all day in Moscow between the two train journeys. Once in Kiev I made a phone call to the number Claire had sent to my Dad, and asked for Sveta. My cousin Ira remembers that my call took her aback. She recalls a foreign voice on a crackly line asking to speak to her mother, who had died two years previously. It was upsetting for her to have to explain that Sveta had passed away. My phone call came out of the blue, she says, she hadn’t received my letter – perhaps I didn’t send one after all; perhaps it got lost in the post, a common occurrence at the time. It took a while to find the address. It was January 1992, just a couple of weeks after the Soviet Union had been disbanded, and already street names in Kiev were changing from Russian to Ukrainian. The map I bought had the new Ukrainian names, while the road signs still had the Russian versions. It was all very confusing. But at last, I found the right building and knocked on the door, my heart pounding with nerves. There I met Ira, then in her late 30s, her husband Sergei, father Mark and two children, Alyosha and Masha – it was usual for three generations to live together in small Soviet apartments. Ira called her sister Mila to come over, and the two women disappeared to the kitchen, conferring in whispers. When they emerged, they told me they were both in agreement. They knew as soon as they set eyes on me that I was family. “You look just like our cousin who lives in Odessa,” they said. Ira wrote to me later in a letter, “You have Unikow eyes” – Unikow being the family name that unites us. Old family photographs confirm that this is undeniably true. I made a second visit to Kiev in early summer that year. Once again, the letter I sent from Voronezh failed to arrive and Ira was out of town. Mila took me back to her little apartment on the left bank of the River Dnieper, shared with her husband Grisha, daughter Yulia and Grisha’s parents. Over the days that followed, they showed me some of the sights of Kiev then took me to their dacha in the country – a rustic wooden house with a garden where they grew vegetables. We travelled there in a tiny car that was so ancient and dilapidated that it felt like it was held together with bits of string. But they were some of the lucky ones. Not many people in Kiev were fortunate enough to own a car. I remember Yulia, aged 8 or 9, skipping around the garden wearing a brightly patterned dress. It was one that Claire had sent from America for Mila when she was a little girl. A gift from the West, it was precious, something to treasure and keep for the next generation. It was discovering my cousins in Kiev that first nurtured my interest in family history, and in the Jewish history of Ukraine more generally. I owe a lot to Ira and Mila and their children, both for this reason and also for the friendships we have developed over the last three decades. They now live in Germany and we keep in touch, mainly on Facebook. Recently Ira, now the family matriarch, has been sharing with me some of her childhood memories and family stories from the post-war years, and these will be the subject of my next article.  The terrible numbers are known to us all: six million Jews died during World War II. Pitifully few of those living in Nazi-occupied Europe survived. But there was one large group of European Jews that did live to see the end of the war. After Germany invaded the Soviet Union in June 1941, around a million Soviet Jews – including up to 400,000 from the territories of Eastern Poland recently annexed by the Soviet Union – were either evacuated by the Soviet authorities or managed to escape on their own to the Central Asian republics of the Soviet Union, enabling them to escape almost certain death. Those who made the journey constituted the largest group of European Jews to survive World War II, and many later emigrated to Israel or elsewhere. Conditions during evacuation were harsh, with cramped, overcrowded living quarters and terrible poverty, while disease was rife. Many succumbed to epidemics including typhus, dysentery and cholera, others to crime and despair. Some were arrested and thousands were deported to remote internal frontiers as “class aliens”. According to some estimates, as many as 300,000 of these deportees perished as a result of disease or starvation. The majority of the of evacuees arrived in 1941-1942 in Central Asia – the Soviet republics of Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan – and the region of the Urals mountains. The Uzbek capital Tashkent was one of the main refugee centres, and many passed through the city before moving on to other towns and villages, while some wound up working on collective farms. Published first-hand accounts of the experiences of evacuees are rare. Until recently, I knew that members of my own family had escaped from Kiev to Central Asia during the war years but had never heard stories of their experience there. My cousin Irina, who was born in Kiev in 1952 and lived there until the 1990s, has filled me in on some of her mother’s and grandmother’s recollections of their wartime experiences in Kokand, Uzbekistan. The authorities organised mass evacuations of Soviet citizens, particularly the cultural, technocratic, and educational elite, as well as entire industrial plants, away from the advancing front. The Soviet government and leading institutes were transferred to Kuibyshev, now Samara, some thousand miles southwest of Moscow. But Irina’s grandfather had been arrested in 1938 as an ‘enemy of the people’ and sent to the gulag. The Soviet authorities had no interest in helping his wife Mira (known to me as Miriam) and two children, Musenka (Moishe) and Sulamia (Sveta), escape to safety, so they had to make their own way. They owe their survival to Mira’s brother Avram – a respected doctor and the youngest sibling of my great-grandfather Meyer. Avram secured places for them on a cart with his wife’s brother, travelling east from Kiev to the city of Izyum in eastern Ukraine, and from there they were able to board a train bound for Kokand. They were robbed during the journey, and all their warm clothes stolen. Once settled in Kokand, Avram managed to find a job in the hospital for his sister. Sulamia went to school and 16-year-old Musenka to a further education college. They lived on a thin gruel of flour and water that Mira was able to bring home from work, and Musenka received a white bread roll at college each day, which he gave to Sulamia, who was suffering from typhus. One day during Sulamia’s illness, when she was alone in the family’s lodgings, a burglar broke in. He left again empty handed: the family was so poor that they had nothing to steal. In 1943, Musenka was called up, first to a military academy in Turkmenistan, on the Afghan border, and then to fight. He was later killed in action in Poland. Mira and Sulamia returned to Ukraine after the liberation, together with Avram, first to Kharkov and finally back to Kiev, in defiance of the authorities, which had refused them permission to return to the city. However grim Mira and her family’s experience, they were some of the lucky ones. Avram’s assistance in finding transport and work for Mira saved them a worse fate. Accounts of the lives of Jewish evacuees in Central Asia are few and far between, so it is impossible to generalise about their experience. But it is known that many congregated for days or weeks in and around train stations, sometimes forced to keep moving when they could find no place to shelter, with the area already overwhelmed by the mass evacuations. Some were able to find work, but many did not. Jobs were often temporary and a large proportion of mostly men worked in the black market. The largely Muslim Central Asian population was undergoing its own difficult and ambivalent process of Sovietisation, and was understandably bewildered by, and often resentful and suspicious of, the sudden influx of “western” evacuees. In spite of this, the local population could also be astonishingly generous given their own poverty and deprivation, sharing their food and inviting the newcomers to join their wedding celebrations. Retired journalist and genealogist Bert Shanas, who has kindly shared his research with me, has unearthed several stories of members of his family evacuated to Central Asia from Ukraine during the war years. Rochel Chasina and her mother fled Zhitomir for Kazakhstan. Before they had even got as far as Kiev, their train was requisitioned by the Soviet army, leaving them stranded in the middle of nowhere. Finally, they reached Kharkov, where they spent a month in a refugee camp, before fleeing again when the Germans drew nearer, this time to a small village near Stalingrad. “The trains were crowded; everybody was trying to flee the approaching Germans, and in those days when you got on a refugee train, you never knew for sure what your destination was. You only knew that the general direction was east,” Rochel recalled. As the front drew closer, she and her mother spent more than two weeks sleeping on a bench at the station. "You had to be at the station all the time because you never knew when a train that could mean your escape would arrive.” A freight train took them to Uralsk, in western Kazakhstan, where they shared a room with two other families. “We had been wearing our shoes for protection for the entire month of the train trip. So when we took them off in the room, patches of our skin and flesh came off with the shoes because everything had been frozen together,” she remembered. Rochel looked for a job, but owning only summer shoes, she was unable to work in winter when the ground was covered in snow. She and her mother both overcame serious illness and finally, a cousin found her a job at a military hospital in Novosibirsk, Siberia, about 1,200 miles to the northeast. There they were able to join other family members, living eight to a room. In 1946, they began a perilous three-year journey that would take them from Russia through Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Germany and France, and finally to Israel. Another of Bert Shanas’ relatives, Rosa Zaydenberg, fled from Kiev to Alma-Ata, Kazakhstan, a journey that took around four months under constant attack from German bombers. Once she finally arrived, Rosa had no warm clothes and no place to stay. She tried to sleep on a bench at the train station, but was chased away and ended up sleeping in a public phone box. She soon found work in a factory and in 1942 was able to bring other family members who were surviving in dreadful conditions in Fergana, Uzbekistan, to join her in Alma-Ata. She rented “one corner of one room” for the three of them, paying rent in the form of food for the landlord’s dog, which she scrounged from the factory where she worked. The family returned to Kiev in the summer of 1945. Another Shanas relative, Faina Sheynise, went on hunger strike to persuade her stubborn father to leave Kiev when the occupation began. He had refused to depart, insisting that praying daily at the synagogue would keep him safe. At last, he agreed to flee and the family reached the chaos of Kiev’s train station shortly before the Germans arrived. They boarded a train heading to Kubah, in the Caucasus mountains, and as the invading army continued to approach, moved on to Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and finally to Osh in Kyrgyzstan, close to the Chinese border. There Faina worked as a seamstress and took a job in a food store. Much of her family got separated during the war, with one sibling in Moscow and two others in Siberia. Faina had no desire to return to Kiev after the war. “Not after Babi Yar, where they killed so many thousands of Jews,” she said. “I just couldn’t go back there,” she recalled. She remained in Osh until 1991, when she emigrated to the US. Faina’s niece, Ida Rosentsvaig, was a baby when the war broke out. She and her family managed to get on an already packed train heading to Siberia, where they spent most of the war in the town of Anzhero-Sudzhensk. Later, they were able to join Faina in Osh. “I remember how warm Osh felt after Siberia and all that snow, and suddenly we had enough food!” she recalled. But Ida’s mother became sick and spent two years in hospital from 1946-1948. Ida was left to fend for herself, while her brother – treated as an orphan – was adopted for a time by a local childless family. Eventually the children’s mother recovered and the family settled in the city of Andijan, Uzbekistan. With grateful thanks to Bert Shanas for allowing me to use his research for this article.  The story of the Jewish shtetl is well known. These once vibrant communities that were so widespread across Eastern Europe until the 20th century were destroyed, first by pogroms and resulting waves of emigration, and later by the anti-religion policies of the Soviet Union, with their final remnants wiped off the face of the earth by the Holocaust. But not so, it seems. A new documentary from the Russian filmmaker Katya Ustinova explores the existence of shtetls in Ukraine and Moldova right up until the 1970s and even beyond. Shtetlers premiered last year and was available to view during Russian Film Week USA in January. Unfortunately, is not yet available in Europe, so I am still awaiting an opportunity to watch it. As the film’s website says, “In those small and remote towns of the Soviet interior, hidden from the world outside of the Iron Curtain, the traditional Jewish life continued for decades after it disappeared everywhere else. The tight-knit communities supported themselves by providing goods and services to their non-Jewish neighbours. The ancient religion, Yiddish language and folklore, ritualised cooking and elaborate craftsmanship were practised, treasured and passed through the generations until very recently.” Ustinova is a Russian-born documentary maker living in New York who previously worked as a producer, host and reporter for a Russian broadcasting company in Moscow. Shtetlers is her first feature-length film. Ustinova’s grandfather was a Jewish playwright, but her family did not identify as Jewish until her father, a businessman and art collector, founded the Moscow-based Museum of Jewish History in Russia in 2012. On discovering modern artifacts from shtetls in the former Soviet Union, Ustinova and her father came to realise that some Jewish communities had continued to exist for far longer than they had thought. Shtetlers tells the stories of Jews in these forgotten shtetls by means of nine first-hand accounts of people who lived in them. In 2015, Ustinova visited several former shtetl residents, who have since scattered around the world. Many of the stories in Shtetlers help break down the myth that only enmity existed between Ukrainians and Jews. Without distracting from the fact that many Ukrainians committed atrocities against the Jewish population before and after – as well as during – the war, the film reminds us of those gentiles who loved and cared for their Jewish friends and neighbours. Meet Vladimir. He was not born Jewish, but converted after his mother – who is honoured at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Centre – sheltered dozens of Jews during the war. Growing up among Jewish neighbours, their culture imbued itself into gentile homes, and he remembers his mother baking challah during his childhood. Vladimir emigrated to Israel and now lives in the West Bank as part of an Orthodox Jewish family. And Volodya and Nadya, Ukrainian farm workers still resident in a former shtetl in Ukraine, who remembered their Jewish neighbours so fondly that they decided to adopt Jewish customs, like making matzo brei and kissing the mezuzah attached to the doorway of their house – which once belonged to Jews – when they enter. Emily, a Jewish shtetler who survived the war, escaped from a concentration camp and was saved by a gentile friend – the sister of a Ukrainian police chief – who brought her family food while they were in hiding. And then there’s the queue of Russian Orthodox Christians coming to Rabbi Noah Kafmansky to solve their problems and obtain his blessing, because “the Jewish God helps better”. In the five years since Ustinova filmed Shtetlers, many of the people she met have passed away. “Their memories are a farewell to the vanished world of the shtetl, a melting pot of cultures that many nations once called their home,” the website says. The trailer is available on the Shtetlers website: shtetlers.com/ And numerous extracts from the film, as well as some gorgeous animated clips, can be found on the Shtetlers Instagram page: www.instagram.com/shtetlers/  When I first began writing my grandmother’s story and turning her recollections into what would eventually become a book, the title I originally had in mind was The Breadbasket. To me, this encompassed much what the people and places in the book were about. Ukraine was known as the Breadbasket of Europe because of its huge grain production. My great-great-grandfather Berl was a grain trader. And bread, or lack of it, played a big role in the family story, from the mill my family owned in the latter part of the 19th century and early 20th, to the prosperity Berl built through his thriving business, to his wife Pessy’s ability to make a ball of dough dance as she kneaded and shaped it in mid-air, and the challah on the Sabbath table. And later, there were the Bolshevik grain requisitions, the great hunger that followed the revolution when there was no bread to be had and my grandmother travelled the land with a basket on her back, bartering food to keep her family alive. But a literary editor who guided my early manuscript advised me to ditch the title. You need something more evocative and compelling, he said. Several weeks later, I finally settled on A Forgotten Land. This was a success and I was pleased with the change. The new title evoked the terrible loss suffered by towns and villages across a wide swathe of Eastern Europe, along with the people who lived there and their way of life. In the Pale of Settlement of the Russian Empire, pogroms, war, famine, disease and emigration had torn Jewish families apart from the 1880s onward and seared the heart out of Jewish communities. The Nazis, of course, would do the rest, not just there but across Europe. The Pale did indeed become a forgotten land, a network of once vibrant communities whose people had all emigrated or died. Three-quarters of a century on from the Holocaust, many people are working hard to bring to light the remnants of the deserted shtetls, to remind us of these communities that have been forgotten for so long. I will highlight just two projects, but please feel free to add others to the comments at the end of this article. The first is a blog called Vanished World, which documents Cologne-based photographer and writer Christian Herrmann’s travels around Eastern Europe and elsewhere in search of visual traces of the Jews who once lived there - destroyed or misappropriated synagogues, overgrown cemeteries, tombstones in the street paving, traces of home blessings on door jambs. “Neglected Jewish cemeteries, ruins of synagogues and other remains of Jewish institutions [are like] stranded ships at the shores of time. The traces of Jewish life are still there, but they vanish day by day. It’s only a matter of time until they are gone forever,” he says. His articles and photographs are both a commemoration and an act of justice towards the men, women and children who died as innocent victims in the Holocaust, and an act of justice to those who survived as well. Christian’s photographs are beautiful and his commentaries on his travels tell a repeated and all-too- depressing tale of crumbling synagogues that were later used as museums, offices or factories during the Soviet era, fragments of tombstones incorporated into buildings or unearthed during construction works, and long-forgotten Jewish cemeteries that are now parks or wastelands. Another project is taking place in Ukraine, where Vitali Buryak, a software engineer from Kiev, has taken on the immense task of attempting to catalogue hundreds of shtetls. He began by creating lists of every settlement with a historical Jewish population of more than 1,000 for each gubernia (province) in central and eastern Ukraine. “My plan is very simple – to write at least a small article for each place on my list,” he says. His articles include old photographs and maps, archival documents, historical references and information about local families as well as numerous photographs of his own. Vitali only recently learnt of his own Jewish roots, and decided to offer his services as a tour guide for Jewish visitors from abroad. One of his early tours brought him to the town of Priluki. “Priluki is the place where I was born, and my grandma is still living there. I contacted the head of the local Jewish community and he showed me places that I didn’t know about before! In my city, where I was born! My grandma didn’t show me the synagogues, she didn’t show me Jewish cemetery, she didn’t show me the Holocaust killing sites, or the sites of the ghetto. I’ve walked on this street, I’ve seen this building before. But I didn’t know it was a synagogue. And it was a shock for me,” he recounts. “I decided to make this website in dedication to the Jews of Ukraine. The purpose of it is the gathering of information and resources from the remaining Jewish communities in Ukraine, as well as the ones that have been destroyed” Vitali says. Vitali’s website can be found here http://jewua.org/ And the Vanished World blog can be found here https://vanishedworld.blog/ |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed