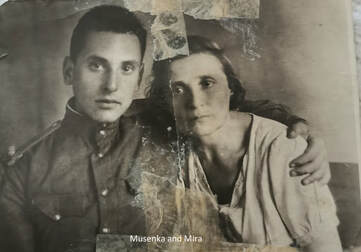

The Soviet Union was not an easy place to live after World War II, and especially for Jews. Those who managed to survive the war by fleeing to Central Asia or the Urals and returned after the German retreat found their homes destroyed, their towns devastated, and their Jewish neighbours slaughtered. In Kiev, then in Soviet Ukraine, where several members of my family lived, nearly 34,000 Jews had been shot at the ravine known as Babi Yar on the edge of the city on 29-30 September 1941. But this was far from the only anti-Semitic atrocity committed by the Nazis in the city. My grandmother’s first cousin Baya was among a group of Jews herded to the banks of the river Dnieper and forced aboard a ship that was set alight. There were no survivors. And few rural Jews from the villages formerly known as shtetls survived the war either. In Pavoloch, my grandmother’s home town, on 5 September 1941 up to 1,500 Jews were shot beside a mass grave dug in the Jewish cemetery. The victims came from many outlying villages as well as Pavoloch, herded to the town for slaughter. The terrible event has become known as the Pavoloch Massacre and even featured in last year’s Amazon Prime series Hunters, which I found myself unable to watch. Several hundred thousand Jews fled to the eastern republics of the Soviet Union in 1941 as the Nazis approached. You can read some of their stories here. Many never went back to the towns they had left, unable to contemplate returning to places where such terrible devastation had taken place. Most, inevitably, would have lost family members or friends to the Nazis. It is hardly a surprise that a great number emigrated to Israel or the United States as soon as the possibility arose, while some remained in Uzbekistan or Kazakhstan, or elsewhere. But thousands of Jews did return to their homes in towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. In my last article I wrote about my grandmother’s aunt Miriam (Mira) and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka), who made it back from Central Asia to Kiev in December 1943. Mira’s son Moishe (Musenka) had been called up earlier the same year to a military academy in Turkmenistan, on the Afghan border, and did not come home with them. To continue their story, in 1944, Musenka was transferred to the front – to Poland. In preparation for his departure, he was moved to an army camp on the outskirts of Kiev, where his mother and sister were able to visit him. Later, from Poland, Musenka wrote that his regiment was preparing for a major offensive in Warsaw. He died on 16 October 1944, ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s final offensive to liberate the Polish capital. He was 18 years old. It was his sister Sulochka, rather than his mother Mira, who received the death notice sent by the Soviet military authorities. Sulochka was 13 and had become something of a tearaway – a fiercely independent girl who skipped lessons and swiped pastries from vendors at the old Jewish market. She hid the letter from her mother, knowing how deeply it would upset her. But Musenka had been a loyal son and always kept in touch regularly with his family. Mira descended into a panic after his letters stopped. She contacted the military authorities searching for information, but when a second copy of the death notice arrived, once again it was Sulochka who intercepted it. Mira wanted to die. She felt she couldn’t live without her precious only son and couldn’t bear not knowing what had happened to him. She returned to the ruins of her pre-war home in the hope that bricks from the half-demolished building would fall and kill her. She more or less ignored her living daughter, Sulochka, amid the pain she felt over her missing son. Her husband Yehuda – exiled to a labour camp near Krasnoyarsk – even wrote a letter to the war commissar Klim Voroshilov with a plea for help in finding any trace of Musenka. Many families waited years, decades even, for their menfolk to return from the war. Some were lucky; many were not. As time passed, the small glimmer of hope that her son was still alive and would one day come home gave Mira the strength to go on living. It was not until 1964, twenty years after Musenka’s death, and after Yehuda – finally liberated from the gulag – had also passed away, that Sulochka confessed to her mother that she had hidden the letters from the military authorities informing them that her brother had died in action. In the end, knowing the truth at last helped ease Mira’s distress. For all those years she had tormented herself with the thought that Musenka might have fallen into the hands of the Banderovtsy – the anti-Semitic Ukrainian nationalists led by Stepan Bandera, who allied with the Nazis and collaborated in the near-total destruction of Jewish life in Ukraine. The torture they inflicted on captured Red Army soldiers was notorious, and all the more so for those of Jewish descent. Mira spent her post-war years enveloped in grief over the loss of her beautiful boy – and yes, photographs testify that he was indeed beautiful. Her love for her daughter remained in the background; it clearly existed, but was rarely overtly demonstrated. Mira could be a stubborn and awkward character and she and Sulochka were often at loggerheads. But Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was 14 when Mira died in 1966, remembers her with warmth and affection. This story will be continued in my next article.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed