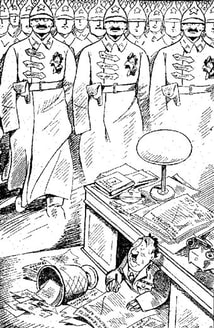

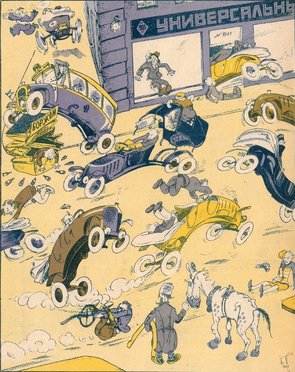

I have spent several days over the summer sitting in at art exhibitions where my paintings are on display. An article about two Soviet cartoonists recently caught my eye, reminding me that many artists over the years have not had it so easy. Boris Efimov was born in 1899 to a family of Jewish petty traders from Kiev. This makes him just a couple of years older than my grandmother, and from the same neck of the woods. In 1922 Efimov was persuaded by his brother Mikhail, a publisher and journalist later known under his pen-name Koltsov, to move to Moscow and earn a living from his art. He became the most lauded Soviet graphic artist of his time, and swung with the tide of official Soviet opinion, meaning that he was well treated by a succession of governments, from Lenin all the way to Putin. Efimov work consisted mostly of flattering caricatures of Soviet celebrities and contrastingly harsh images ridiculing the regime’s enemies. Thanks in part to his brother, he became acquainted with many important personalities including politicians, publishers and critics. In 1924 he was described by Leon Trotsky (before the latter’s political downfall and exile) as ‘the most political of our graphic artists’. Trotsky wrote the preface to Efimov’s first album of drawings published in 1924 and the artist repaid him with subtle compliments (see illustration, left: ‘British Military Expert Repington is Trying to Define the Exact Size of the Red Army’, 1924. Every soldier is shown with the face of Leon Trotsky, alluding to the fact that he was a founder of Red Army. David King Collection, Tate Archive). In 1926, after the British and Polish governments approved the shooting of four communists in Lithuania, Efimov published a cartoon showing Austen Chamberlain, the British foreign minister, and Polish premier Jozef Pilsudski applauding the execution. The British Foreign office issued a diplomatic memorandum to the Soviet Union, which was seen as something of a coup for Efimov. Pilsudski did not react. Victims of political persecution became key targets for Efimov’s cartoons, even though many were former contacts and patrons of his. He attended the show trials of 1937 and 1938, which destroyed Stalin’s political opponents, sketching defendants that often he knew personally. These included the Soviet diplomat Christian Rakovsky, the Troskyite and journalist Karl Radek, and Nikolai Bukharin, one of Stalin’s leading rivals. His cartoons sometimes appeared on the same day as their subjects’ executions. Efimov’s brother Koltsov was arrested in 1938 and executed two years later, leaving Efimov fearful for his own arrest. Luckily for him, his reputation within the regime was strong enough to save him. Stalin considered him useful and personally forbade anyone from harming him. Naturally, in return, Efimov was unable to refuse to undertake work in support of the regime. Throughout the war years he specialised in drawings of Hitler and other Nazis, images that proved popular among the Soviet forces. Efimov was awarded the most prestigious state honours, including several Stalin prizes and an Order of Lenin. He became the most celebrated cartoonist in the Soviet Union and, probably, the country’s richest artist. Albums of his caricatures were printed in their millions in the USSR and abroad. Efimov died in 2008, at the age of 108. During his long life he created more than 700,000 pictures, and until his final years he continued to attack enemies of the state. When asked how he managed to live for so long, he replied, “I don't know. Maybe I have lived two lives, one of them for my brother”. Efimov’s life contrasts sharply with that of fellow Soviet cartoonist Konstantin Rotov (1902–1959), who was loved by the people, but was sentenced by Stalin to fourteen years of prison and exile. Rotov had been extremely popular in the interwar years, indeed he was better known in his time than the now famous artists of the era Kazimir Malevich, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Marc Chagall. His mildly humorous cartoons appeared on an almost daily basis. In 1939 one of his drawings provided the image for a large mural in the Soviet pavilion in the World Exhibition in New York. He also produced the occasional political caricature, ridiculing so-called enemies of the people, but only did so reluctantly. In 1940 Rotov was arrested for a cartoon titled ‘Closed for Lunch’ depicting a horse and sparrows, that he had drawn in 1934 but was never published. The sparrows are shown patiently waiting for their lunch (horse’s dung) while the horse is eating from the nosebag. The hint at the hunger in the USSR was obvious to his contemporaries. A fellow artist saw the picture and reported Rotov to the secret police. He was charged with ‘defamation of the Soviet trade and cooperation’, tortured and sentenced to eight years in a labour camp. When his term came to an end, Rotov was sentenced again, this time to exile in Siberia. He was able to return to Moscow only in 1954, after Stalin’s death. He immediately resumed drawing, producing illustrations for fairy tales and fantastical stories, such as Adventures of Captain Vrungel and Old Khottabych. These became (and still are) very popular, although few remembered his name and past fame. He died in 1959, his health damaged during his years of imprisonment. This blog post is taken from an article by the historian and Tate Library Cataloguer Andrey Lazarev. View the full article here: https://www.tate.org.uk/research/features/two-soviet-cartoonists  Konstantin Rotov, ‘Traffic in Two Years According to the Promises of Moscow Authorities: So Many Buses and Taxis that a Simple Horse can Startle’, 1927. David King Collection, Tate Archive

0 Comments

|

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed