|

Next Monday, 18 March, marks the tenth anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The move followed swiftly on from Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, which culminated in then-president Victor Yanukovych’s flight from Kyiv in late February 2014. Russia took advantage of the chaos in Kyiv, quickly seizing military bases and government buildings in Crimea.

Armed men in combat fatigues began occupying key facilities and checkpoints. They wore no military insignia on their uniforms and Russian president Vladimir Putin insisted the “little green men” – as Ukrainians called them – were acting of their own accord, and were not associated with the Russian army. Only later did he acknowledge the role of the Russian military in the occupation, even awarding medals to those involved. By early March, Russia had taken control of the whole peninsula and its ruling body, the Crimean Supreme Council, hastily organised a referendum for 16 March. The vote went ahead without international observers and was widely condemned as a sham. It offered residents two options: to join Russia or return to Crimea’s 1992 constitution, which gave the peninsula significant autonomy. There was no option to remain part of Ukraine. The result, predictably, was landslide in favour of becoming part of Russia. Turnout was reported to be 83%, with nearly 97% voting to join the motherland, in spite of the fact that Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars made up nearly 40% of the population. The accession treaty was signed two days later. In May that year, a leaked report put turnout at 30% with only half of all votes cast in favour of becoming part of Russia. The annexation of Crimea gave an immediate boost to Putin’s approval ratings, following a turbulent period of pro-democracy protests across Russia in 2011-12. In the face of a weak economy, Putin’s re-election campaign in 2012 had focused on appealing to Russian nationalism, and the swift and bloodless coup in Crimea provided a perfect model for his propaganda narrative. The peninsula had first become part of Russia in the eighteenth century under Empress Catherine the Great, who founded its largest city, Sevastopol, as the home of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Crimea was part of the Russian republic of the Soviet Union until 1954, when it transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet republic. When the USSR collapsed in December 1991, the successor states agreed to recognise one another’s existing borders. Russia’s seizure of Crimea violated, among other agreements, the UN Charter, the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances for Ukraine and the 1997 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Ukraine and Russia. Crimea has experienced significant changes over the past ten years. Ethnic Russians made up around 60% of the population in 2014 — the only part of Ukraine with a Russian majority. Since then, around 100,000 Ukrainians and 40,000 Crimean Tatars are estimated to have left the peninsula, while at least 250,000 more Russians have moved in, pushing the ethnic Russian population above 75%. Many are members of Russia’s armed forces as the Kremlin has built up its military presence on the peninsula. Others are civilians lured by Russian government incentives, such as job opportunities, higher salaries, and lower mortgage rates. Crimean Tatars complain of intimidation and oppression. They are routinely searched, interrogated, accused of terrorism offences and sent to prisons thousands of kilometres away. In prison, they are denied access to medical care, put in isolation cells and forbidden from communicating with relatives or lawyers, or from practising their religion, according to a report in the Kyiv Independent. Of the ethnic Ukrainians who remained in Crimea in the years after annexation, a significant number have since been expelled, imprisoned on political grounds, forced to move to Russia or mobilised into the Russian military. Amid the ubiquitous narrative of Crimea as historically and enduringly Russian, and with public spaces dominated by Soviet and war nostalgia, Crimeans today are afraid to identify as Ukrainian. The high-tech security fence erected on the border between Crimea and mainland Ukraine in 2018 now symbolises separation from family and friends elsewhere in the country. Moscow has poured more than $10 billion in direct subsidies into Crimea, investing heavily in schools and hospitals, as well as military and civilian infrastructure. Crimea today accounts for around two-thirds of all direct subsidies from the Russian federal budget. But many local businesses have suffered, particularly with the decline in tourism, which once accounted for about a quarter of Crimea’s economy. And as Ukrainian products in shops were replaced with higher-priced Russian goods, and later as the value of the rouble fell, prices have spiked. Western sanctions against Russia have also taken their toll on Crimea’s economy. Crimea was one of the Russian regions with the lowest income levels in 2023, according to the Russian state-owned rating agency RIA. Russia has also funded major construction and infrastructure projects, such as the Tavrida highway, which opened in 2020 connecting the east of Crimea with its major cities in the southwest, and the highly symbolic Kerch bridge linking Crimea to Russia, opened to great fanfare by Putin in 2018. Today parts of the Tavrida highway have reportedly begun to buckle, leading to a rise in road traffic accidents. The Kerch bridge has sustained serious damage from Ukrainian attacks and by December last year was still not fully restored. Back in 2014, many Russians in Crimea were euphoric about rejoining the motherland, having always identified with Russian rather than Ukrainian culture and customs. They welcomed the attention that Putin lavished on them, and the influx of Russian cash meant that wages and pensions, now paid in Russian roubles, initially increased. The euphoria has since subsided, and particularly since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many Crimeans are fed up with living in a territory that is isolated, highly militarised, tightly controlled, economically weak and under attack from Ukrainian forces.

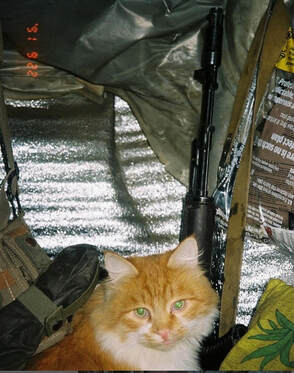

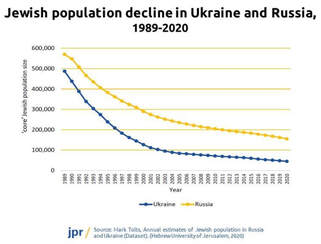

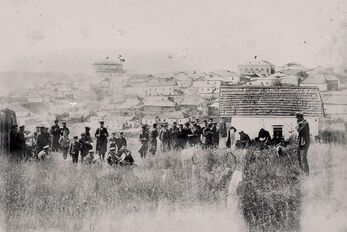

0 Comments

This week marks the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Seeing satellite images of a long line of Russian tanks heading towards Kyiv on that awful morning, few believed that the war would last more than a handful of days; weeks at most. I wrote at the time that Russian president Vladimir Putin had a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him, as he stepped up his attempts to recreate Stalin’s Soviet empire by taking control of Ukraine. Now that whiff has become more of a stench. The death of Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most prominent critic, on 16 February makes the parallels between the two dictators starker than ever. Like Stalin, Putin views the outside world as a hostile and threatening place and brooks no dissent. Stalin subjected his opponents to show trials, found them guilty on trumped-up charges and had them shot. Today, anyone who publicly opposes Putin’s regime, who attempts to tell the truth, expose the corruption, is a grave threat. Putin’s methods of silencing opponents are more varied – imprisonment, poison, shooting, defenestration, a plane falling from the sky. Again like Stalin, Putin heads a cruel and corrupt administration, but has built a personality cult around himself to appear as a paternalistic leader who has the best interests of his citizens at heart. Both regimes have been guilty of hiding or falsifying data and masking the truth with a state-sanctioned view of world events and a thick veneer of propaganda. At the time of writing, the cause of Navalny’s death is unclear. A video taken the previous day showed him looking surprisingly well given the inhumane conditions in which he was incarcerated. His family and legal team have repeatedly been refused access to a mortuary where his body is believed to lie. Just days before Navalny’s death, another Russian politician, Boris Nadezhdin, was barred on technical grounds from standing against Putin in next month’s presidential election. Nadezhdin has been careful to play by the Kremlin’s rules, to avoid calling out or criticising Putin, but he is a vocal opponent of the war in Ukraine. Russia-watchers had considered he might be allowed to remain on the ballot to give the appearance of competition, and to provide a narrative for Putin to rally against. But Nadezhdin proved too popular. A hundred thousand Russians flocked to sign supporter lists to enable him to stand against Putin, so the electoral commission ruled that thousands of the signatures he had gathered were fraudulent. Nadezhdin continues to appeal the ruling, but he must now be looking over his shoulder in case FSB officers are sent to arrest him, just as those who opposed Stalin’s regime lived in fear of a knock at the door in the middle of the night. Another parallel between Putin’s Russia and Stalin’s Soviet Union can be found in the Russian-occupied cities of eastern Ukraine, where the Kremlin is carrying out ethnic cleansing just as it did in the 1940s. In Mariupol, Zaporizhzhia and other cities located in the regions where the Kremlin held rigged referendum votes on becoming part of Russia, the occupying authorities are doing all they can to wipe out Ukrainian identity. Mariupol, before the war a pleasant, leafy coastal city on the Sea of Azov, was besieged and almost razed to the ground in the spring of 2022. Now smart, Russian-built apartment blocks line newly reconstructed avenues planted with lawns and neat rows of trees. In these apartments live recently arrived Russians, shipped in from the Motherland with the promise of better housing, good jobs, higher wages. Many of the previous inhabitants fled the bombardment back in 2022, or were killed or taken prisoner during the siege. What’s more, around 5 million Ukrainians from the occupied territories are estimated to have been deported to Russia in the last two years, including 700,000 children. Those who stayed and survived, or returned, were forced to acquiesce with the occupying authorities, to become Russian. Access to social services, including pensions and maternity payments, is only available to those with Russian passports. This in turn means babies are born to Russian rather than Ukrainian nationals, and inherit Russian citizenship. They will go to schools where they are taught in Russian, be subject to Russian cultural influences and learn a Russian history curriculum filled with hateful rhetoric about Ukrainian Nazis. Refusal to apply for a passport of the occupying power leaves defiant Ukrainians living a shadowy undercover existence, while any show of insubordination is likely to land them in a Russian prison. Crimea has experienced the same manipulations of population and bureaucracy for the last decade, since the Russian annexation in March 2014. Ukrainians were forced out or coerced into giving up their citizenship, native Russians were encouraged to settle, and only those holding Russian passports can access schools, hospitals and social services. Most Russians, and many outside Russia, have long believed that Crimea was not really Ukrainian, that it was something of a Russian enclave inside Ukraine. After all, it had only become part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954, transferred by then premier Nikita Khrushchev from the Russian Federation (for reasons I discussed in a previous article). Crimea’s population at that time was roughly 75% Russian and it was home to the Soviet (now Russian) Black Sea Fleet. But that only tells a small part of Crimea’s story. The peninsula, strategically located at the centre of the Black Sea, was wrested from the Ottoman Empire by Russia in 1783 under Catherine the Great. Its population for centuries had been predominantly Crimean Tatar – a Turkic-speaking, Sunni Muslim ethnic group. In 1944, Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars en masse to Siberia, the Urals and Central Asia and expelled Crimea’s smaller populations Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians. The peninsula was repopulated with ethnic Russians. Since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, many Crimean Tatars had returned to their homeland, along with other ethnic groups, who were granted citizenship rights by the Ukrainian government.  At least 95 Ukrainians known for their work in the creative industries have been killed since Russia’s full-scale invasion began nearly two years ago, according to the writers’ association PEN Ukraine. The organisation tracks losses among writers, publishers, musicians, artists, photographers, actors, filmmakers, and other creative professionals whose stories appear in the information field. It is likely that many more artists have been killed in the war than appear on PEN’s list. On 7 January the poet Maksym Kryvtsov was killed by artillery fire in Kupiansk, near Kharkiv, one of the key fronts in Moscow’s winter offensive. His loyal companion, a ginger cat, was killed with him. Kryvtsov, aged 33, had been hailed as one of the brightest hopes of Ukraine’s young, creative generation. Kryvtsov was an active participant in the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity – better known in the West as Euromaidan – and joined Ukraine’s armed forces as a volunteer in 2014, when the war against Russian separatists in the Donbas region began. He was later involved in organisations helping to rehabilitate fellow veterans and help them reintegrate into society, and also worked at a children’s camp. He was, by all accounts, far from the stereotypical image of a fighter. Kryvtsov returned to army in February 2022 when Russian forces invaded Ukraine. Comrades knew him by his call sign Dali – a reference to the curling moustache he grew in imitation of the Spanish artist Salvador Dali. “I think the war is a kind of micellar water that washes cosmetics off: from a face, streets, plans and behaviours. It’s like a hoe cutting through sagebrush, leaving a bitter aftertaste of irreversibility. In war, you become your true self, no need to play a role. You are simply a human, one of billions who ever lived on the Earth, sharing the commonality of breath. There’s no time for love at war. It lies abandoned next to a trash pile and disappears like a grandfather in a fog, lost somewhere behind this summer’s unharvested sunflower fields of a heart,” Kryvtsov said in a 2023 interview with Ukrainian publishing and literary organisation Chytomo as part of its Words and Bullets project with PEN Ukraine. Even through the chaos of war, Kryvtsov continued to write poetry. Many of his poems reflect on the harsh reality of war and the contrast between war and ordinary, civilian life. His first poetry collection Вірші з бійниці (Poems from the Embrasure) was hailed by PEN Ukraine as one of the best books of 2023. Within days of his death, the book’s entire print run had sold out and the reprint had racked up thousands of preorders. Profits from the book will be split between Kryvtsov’s family and projects to bring books to the armed forces. Hundreds of people gathered at St Michael’s monastery in Kyiv to attend a ceremony to honour Kryvtsov, ahead of a funeral in his hometown of Rivne. Some carried copies of his book, others a bouquet of violets, a reference to Kryvtsov’s final poem, posted on Facebook the day before he died (see below). The second part of the memorial service was held in Kyiv’s central Independence Square, the scene of the Euromaidan revolution in which Kryvtsov had participated. Mourners took turns stepping up to a microphone to share their memories of Kryvtsov and his poetry. He “left behind a colossal height of poetry,” said Olena Herasymiuk, a poet, volunteer and combat medic, who was a close friend of Kryvtsov. “He left us not just his poems and testimonies of the era but his most powerful weapon, unique and innate. It’s the kind of weapon that hits not a territory or an enemy but strikes at the human mind and soul.” (quote from the Associated Press) In an outpouring of grief on social media following Kryvtsov’s death, many drew parallels with Ukrainian cultural figures killed during the Soviet Union’s repression of writers and artists in the 1920s and 30s. Among these is the mighty figure of Isaac Babel, whose most famous collection of short stories Red Cavalry was written a century ago, inspired by Babel’s experiences as a war reporter in the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. I have recently been rereading the Red Cavalry stories and had intended my latest article to be about the historical parallels between Babel’s commentaries on war and contemporary war writers in Ukraine. That will have to wait for next time. Instead, I leave you with the prophetic poem Maksym Kryvtsov wrote the day before he died, and an extract from his poem about his ginger cat, posted on Instagram a few days earlier. My head rolls from tree to tree like tumbleweed or a ball from my severed arms violets will sprout in the spring my legs will be torn apart by dogs and cats my blood will paint the world a new red a Pantone human blood red my bones will sink into the earth and form a carcass my shattered gun will rust my poor mate my things and fatigues will find new owners I wish it were spring to finally bloom as a violet My Ginger Tabby When he falls asleep slowly stretches his front legs he dreams of summer dreams of an unscathed brick house dreams of chickens running around the yard dreams of children who treat him to meat pies my helmet slips out of my hands falls on the mud the cat wakes up squints his eyes looks around carefully: yes, they’re his people: and falls asleep again. Taken from Wikipedia, translation credited to Christine Chraibi  Since February 2022, more than six million Ukrainians have fled abroad in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Another 8 million are internally displaced, mostly in western Ukraine. And around a million Russians have also escaped abroad, many because of their opposition to the war or to avoid the draft under Russia’s partial mobilisation. Among these numbers are tens of thousands of Jews. According to Israel’s Ministry of Aliyah and Integration, more than 40,000 immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus in the year to February 2023. Many members of the Ukrainian Jewish community have also found refuge in other European countries, but those who arrived in Israel held an advantage in having an immediate right to citizenship. The number of Ukrainians with at least one Jewish grandparent – and therefore qualifying for Israeli citizenship by Israel’s Law of Return – was 200,000 in 2020, according to the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR), while the number who identify as Jewish (the ‘core’ Jewish population) was estimated at 45,000. Since the end of the Cold War, the Jewish population of Russia and Ukraine has fallen by 90%, according to the JPR, continuing an exodus that had begun in the early 1970s. An easing of the ban on Jewish refusenik emigration from the Soviet Union at that time allowed approximately 150,000 Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a further 400,000 departed, with more than 80% heading to Israel and the remainder mostly to Germany and the US – several members of my own family among them. In 2014, the number of Ukrainian Jews immigrating to Israel jumped by 190% in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine. Jewish emigration from Russia also spiked and the numbers coming to Israel from both countries stabilised at this higher level in the eight years leading up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With another war now raging in the Middle East, some of those displaced by the hostilities in Ukraine have had to flee twice over. Among them are more than sixty children from the Alumim children’s home near Zhytomyr in western Ukraine. Some are orphans from the surrounding towns and villages within the historic Pale of Settlement, others have parents who are unable to provide a stable home for them. On 24 February 2022, bombs began to fall around the home, which was located close to a Ukrainian air base. Its founders, Rabbi Zalman Bukiet and his wife Malki, had made advance preparations in case of a Russian attack and were able to quickly evacuate the children to the west of the country by bus. After a few days, when it became clear that the war would not reach a swift conclusion, they crossed the border into Romania and from there boarded a plane to Israel. The logistics of the transfer were complex as almost none of the children had passports. Some of their mothers and other community members joined the group until it numbered 170 people. “El Al Airlines wanted us to finalise the number of seats we needed, and the paperwork was an open question,” Rabbi Bukiet recalled. One child had been away visiting his home village when the war broke out and had to be driven to Romania by taxi for a fare ten times higher than the standard rate. Once in Israel, the group was hosted at the Nes Harim education centre in the Jerusalem Hills. “We came for a month and stayed for six,” Rabbi Bukiet said. But as the new school year came round, he needed to find a more permanent home for the children. The group moved to Ashkelon, a coastal town in southern Israel, and rented two accommodation buildings – one for girls and one for boys – as well as apartments for the 16 families that had come with them from Zhytomyr and a home for the rabbi and his own family. “And so Ashkelon became home. The kids learned Hebrew, gained Israeli friends and integrated into the local community. The mothers took jobs and learned to navigate life in Israel. And we all got used to the new normal,” Rabbi Bukiet said. He and Malki arranged visits for a family member from Ukraine for each child, along with outings and activities. With the next school year due to begin, the group decided to stay another year in Ashkelon. Until history repeated itself. On 7 October the sirens once again blared at six am, just as they had in Zhytomyr 18 months or so earlier. Once again, the sound of gunfire and explosions reverberated around them. Rabbi Bukiet and his own family ran to a shelter but were unable to reach the children’s dormitories until midday. By the afternoon, the constant sirens had eased the he and Malki were able to gather the children together in a larger shelter. That night they made plans to relocate again, further north into Israel. Today the inhabitants of the children’s home are based in the Hasidic village of Kfar Chabad, not knowing how long they will stay. Safe for now, their future is uncertain once again. The full story of the Alumim children's home can be found here: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/6186434/jewish/How-Our-Childrens-Home-in-Ukraine-Was-Uprooted-Again-by-War-in-Israel.htm  When Hamas terrorists entered southern Israel last month, they committed the biggest mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust. That on its own is a desperately chilling thought. But Israel’s response to the attacks has unleashed a wave of antisemitism around the globe on a scale not seen since the middle of the last century. Words that for decades have been unsayable in public are now being chanted in the streets of our major cities. And in Russia, a country with a devastating history of antisemitism that had until recently been quashed, pogroms have broken out once again. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jews in Russia suffered wave after wave of pogroms – anti-Jewish riots that involved terrorising communities, attacking Jewish homes and businesses, humiliating and maiming, rape and murder. Last weekend Russia witnessed its first pogrom in sixty years. In Dagestan, a mainly Muslim region of southern Russia bordering Chechnya, an angry mob shouting antisemitic slogans stormed the airport of the regional capital Makhachkala. The rioters broke through security barriers onto the runway with the intention of attacking passengers arriving from Tel Aviv, fuelled by rumours circulating on social media that the plane was carrying refugees from Israel. The rumours were later proven to be untrue. Elsewhere in Dagestan, a riot broke out outside a hotel in the city of Khasavyurt, because Israeli refugees were believed to be sheltering inside. The protestors pinned a sign to the door: Entry strictly forbidden to Israelis (Jews). And in Nalchik - located, like Dagestan, in the North Caucasus region - a mob attacked and set alight a Jewish cultural centre that was under construction. The words Death to Jews were daubed on its wall. These events took place in spite of strict rules prohibiting public demonstrations in Russia, implemented to stifle protest against the war in Ukraine. The pogroms of the past took place across the Pale of Settlement, where Jews were restricted to living in Tsarist times – in present day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and the western fringes of Russia. These regions had been absorbed by Russia during the partitions of Poland under Catherine the Great in the late 18th century. Jews had long been present in great numbers in Poland because its liberal policies contrasted with most other parts of Europe at the time; Jews were welcomed for their skills in commerce that helped bolster the economy. But Russia was far less tolerant and pogroms were a direct result of an official policy of antisemitism. Today’s pogroms in Dagestan derive from sympathy with Palestinians under Israeli bombardment in Gaza. With a mostly Muslim population, Dagestan has historically been more closely aligned with the Middle East than with Russia. But it is also home to Russia’s oldest Jewish community. Jews have lived in the region since Biblical times and as Jews from elsewhere in Russia have emigrated in huge numbers, mostly to North America and Israel, Dagestan today is home to Russia’s largest Jewish community. Just as the pogroms of the past were a manifestation of official antisemitism in the Russian Empire, the pogroms in Dagestan reflect a change in sentiment in the echelons of power in Moscow. While the Vladimir Putin of the past spoke out against holocaust denial and xenophobia, the Russian president has in recent months ratcheted up antisemitic rhetoric as a reaction to Russia’s failings in the war in Ukraine, not least with his derogatory comments about Ukraine’s Jewish president Volodymyr Zelensky (see my article on the subject here). Putin’s reaction to the violence in Dagestan has been to blame Ukraine and the West, accusing Russia’s enemies of fomenting unrest to destabilise the country. The violence in Dagestan continues a worrying trend for Putin, demonstrating again how his authority is being undermined. Having risen to power almost a quarter of a century ago, Putin cemented his popularity with a reputation for restoring Russia’s territorial integrity and stability after the chaotic unravelling of the 1990s. It was his quelling of violence in Dagestan and neighbouring Chechnya that helped reinforce the strongman image that the president has sought to project ever since. But Putin’s obsessive focus on trying to destroy Ukraine has led him to turn a blind eye to unrest in Russia’s provinces that threatens to undermine his reputation and the sense of order and stability that he has so painstakingly nurtured. The attempted mutiny in June by his once loyal ally Yevgeny Prigozhin was the first clear manifestation of Putin’s authority beginning to unravel. Unrest in the North Caucasus may be the next.  Vladimir Putin has been accused of multiple crimes and offences over the years, but until recently, antisemitism wasn’t one of them. In the last few months, he has come in for criticism from the West, from Israel and the Ukrainian leadership for a spate of antisemitic comments. Putin appeared on TV in early September ranting that “Western masters” installed Volodymyr Zelensky, “an ethnic Jew, with Jewish roots, with Jewish origins” as Ukraine’s president “to cover up the anti-human essence that is the foundation…of the modern Ukrainian state” and “the glorification of Nazism.” The diatribe followed comments made at the St Petersburg international economic forum in in June, when Putin was asked about the apparent contradiction of Ukraine being a Nazi state led by a Jew. “I have a lot of Jewish friends. They say Zelensky is not a Jew; he is a disgrace to the Jewish people,” he said. And most recently, speaking at an economic forum in Vladivostok, Putin said of the former senior Kremlin official Anatoly Chubais, who fled Russia after last year’s invasion of Ukraine and is reportedly living in Israel, “He is no longer Anatoly Borisovich Chubais, he is some sort of Moishe Israelievich, or some such.” The brand of ethnic nationalism that Putin has started to espouse sits rather strangely. Firstly, there’s that awkward issue in his repeated claims to be trying to “denazify” Ukraine, that the country’s leader is a Jew who lost several members of his family in the Holocaust. To those raised with a Soviet (or post-Soviet) view of history, this is less paradoxical than it seems. According to Soviet historiography, no specific emphasis was placed on the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, rather the focus was on the suffering of the Soviet people as a whole. And indeed, the suffering of the Soviet people was terrible, Hitler’s regime classed Slavs as sub-human and Communists were a mortal enemy. There was little awareness during Soviet times that the Jews had suffered any more than the rest of the population and many Russians have held onto that mindset. Putin’s antisemitic outpourings echo comments made in May last year by his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, comparing Zelensky with Hitler. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst antisemites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood. But the conflation of Zelensky and Nazism doesn’t fully explain Putin’s recent antisemitic outbursts. According to historian Artem Efimov, Editor-in-chief of Russian independent media outlet Meduza’s Signal newsletter, the Russian president is exploiting rhetoric to serve his purpose, whether that rhetoric is Marxist, right-wing or, indeed, antisemitic. His words are not based on any deep, systematic beliefs – for Putin has no ideology of his own – but serve as a means to justify his actions, Efimov says. Most notably, Putin repeatedly manipulates the collective memory of Russia’s struggle against Nazism in World War II – or the Great Patriotic War as it is known in Russia – to legitimise his imperialist ambitions in Ukraine. In pivoting towards antisemitism, Putin is repeating an age-old tendency to create a distraction, a scapegoat even, as his strongman image frays and begins to fall apart. As I have written before, Putin has more than a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him. Stalin, amid the paranoia and insecurity that characterised the final years of his rule, repeatedly resorted to antisemitism to push the blame onto others. The post-war years were characterised by Stalin’s purge of “rootless cosmopolitans”, a reference largely to Jews, whose loyalty to the USSR was questioned with the formation of the state of Israel in 1948. Well-known members of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee, formed during the war to organise international support for the Soviet military effort, were arrested, tortured, and executed. Shortly before his death in 1953, Stalin launched another anti-Semitic purge in the form of the “Doctor’s Plot” – an alleged conspiracy by a group of mostly Jewish doctors to murder leading Communist Party officials. The plot was thought to be a precursor to another major purge of the party, and was halted only by Stalin’s death. Moscow’s former chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, has repeatedly warned of rising antisemitism in Russia and urged Russian Jews to leave the country while they still can. Rabbi Goldschmidt resigned in July 2022 because of his opposition to the war and lives in exile in Israel. Tens of thousands of Russian Jews have already emigrated to Israel since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February last year, the largest wave of departures since the fall of the Soviet Union.  Ukraine doesn’t rank high on the holiday bucket list for most of us right now. But thousands of Hassidic Jews have ignored warnings about travelling to a war zone and flocked to the small town of Uman, some three hours south of Kyiv, for an annual new year pilgrimage. They came to worship at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov who was buried in Uman in 1810. Not all are religious Jews, for according to tradition, the rabbi promised to intercede on behalf of anybody praying at his grave on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. This year around 35,000 pilgrims arrived in Uman (up from the 23,000 who visited last year) in spite of warnings from the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities not to travel because of the risk of Russian air attacks and insufficient bomb shelters for the influx of visitors. Some brought young children with them, believing that a child who visits the grave site before the age of seven will grow up to be without sin. A small number of pilgrims have even been known to bring newborn babies to be circumcised in Uman, in spite of a lack of medical facilities for the procedure in Ukraine. Visitor numbers are only slightly down on the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, even though Uman has been targeted on several occasions. In April more than 20 missiles struck the town killing 24 people including several children in a residential district. It last came under Russian missile attack in June. The front line lies around 200 miles to the south. “It is very dangerous. People need to know that they are putting themselves at risk. Too much Jewish blood has already been spilled in Europe. How can you take such a risk?” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this month. With Ukrainian airspace closed, the journey to Uman is long, costly and uncomfortable, involving a flight to Poland, trains, minivan taxis and an inevitable long wait at the border. But the pilgrims remain undeterred in spite of the danger, expense and logistics of holidaying in a war zone. Some are firm in the belief that their Rabbi will protect them from beyond the grave; others just come to party and have a good time. Most come from Israel and spend up to a week in Uman around Rosh Hashanah. Although women are allowed on the pilgrimage, the vast majority of the visitors are men. The annual Jewish gathering has become the town’s major source of income, with pilgrims charged a $200 fee to visit. In recent years, the rabbi’s grave has been renovated with funds donated by Jewish tycoons from around the world. Hotels and hostels have popped up and locals have carried out house renovations to provide accommodation priced at hundreds of dollars a night. Those who can’t afford the exorbitant room prices pitch tents in courtyards or vacant lots. A whole hospitality industry has built up around the pilgrims, offering kosher food and drink at vastly inflated prices, using Hebrew signage and accepting payment in dollars or Israeli shekels. Most of the business owners are Israelis. Dozens of Israeli families moved to Uman in the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The annual influx of bearded, black-robed, skull-capped men makes quite an impact in this quiet town. While the visitors provide Uman with much-needed cash, relations between the pilgrims and the townsfolk are not always harmonious. Locals complain about the loud music, drunkenness, fighting and excessive litter. They resent the police cordons and checkpoints that prevent them from going about their daily business; and they question how the authorities are spending the money collected from the pilgrims, citing widespread corruption. Imagine a massive rave – albeit a religious one – taking over the streets of a small, unexceptional town and you start to get the picture. The Hassidic music blasting from speakers in the streets is imbued with a techno twist. Alcohol and drugs are much in evidence, as is prostitution. It’s hard to put a number on the percentage who come to celebrate and party, not just to pray. There’s a heavy security presence, even in peacetime, but it was stepped up this year in light of the added dangers of war. Police numbers have increased since 2010, when a young Israeli was stabbed in a brawl and ten pilgrims were deported after violent clashes broke out. Violence in Uman is nothing new. In 1941, under German occupation, the Nazis murdered 17,000 Jews here and destroyed the Jewish cemetery, including the grave of Rabbi Nachman, which was later located and moved before the area was redeveloped for housing. The original burial site was close to a mass grave for victims of another Jewish massacre, one that took place in 1768 as part of the Haidamak uprisings. The Uman pilgrimage began shortly after the rabbi’s death in the early 19th century and attracted hundreds of Hassidic Jews from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland until the Russian Revolution of 1917 closed the borders. The photo below dates from this period. In spite of the Communist regime’s clampdown on religious practice, a trickle of pilgrims continued to visit the grave site, including some Soviet Jews who made the journey in secret and were exiled to Siberia as a consequence. From the 1960s, small numbers of American and Israeli Jews travelled to Uman either legally or clandestinely. In the late 1980s, travel to the Soviet Union became easier and the number of pilgrims began to grow. Around 2,000 made the journey to Uman in 1990, rising to 25,000 by 2018.  Warsaw is possibly the most fascinating city I have ever visited. Its glorious old market square, lined with Baroque-style merchants’ houses, rivals those of Krakow, Prague or Brussels. And yet Warsaw’s old town was reconstructed from scratch in the middle of the twentieth century. Somehow the knowledge that the colourful facades are mere decades rather than centuries old added to my appreciation of them – each one painstakingly rebuilt using 18th century paintings of the city by the Venetian artist Bernardo Bellotto as a blueprint. That this reconstruction was carried out during a period when Stalinist architecture dominated in the Soviet bloc makes it doubly remarkable. The rebuilding of Warsaw itself could, in the coming years, serve as a blueprint of another kind – as a route-map for the reconstruction of Ukrainian towns and cities after months of Russian aerial bombardment. While much of Europe experienced destruction on a monumental scale during World War II, the fate of the Polish capital was uniquely cruel. Most of the city was razed to the ground in retribution for the failed Warsaw Uprising of August-September 1944, when the Polish resistance attempted to liberate the city from Nazi occupation. Despite being poorly equipped, the Poles succeeded in killing or wounding several thousand German fighters in a battle lasting for two months, but at a terrible cost. Up to 200,000 Polish civilians were killed, mostly in mass executions, and once the Germans had quelled the uprising, they systematically destroyed what remained of the city, reducing more than 85% of its historic old town to ruins. Today we can only imagine how daunting the task of reconstruction must have seemed. Indeed, some suggested at the time that what remained of Warsaw should be left as a memorial and the capital relocated elsewhere. Many residents and refugees, who returned once Soviet and Allied forces reoccupied the ruined city, were formed into work brigades tasked with clearing the vast amounts of debris, as were German prisoners of war. It was estimated that the sheer volume of rubble – around 22 million cubic metres of the stuff covering almost the entire city – meant that it would take 20 years to transport it out of the city by daily goods trains. Amid the post-war scarcity, Poland lacked the financial resources to purchase construction materials. And the hundreds of brickworks that had flourished in Warsaw before the war – many of them owned by Jews – no longer existed. If the city was to rise from the ashes, the only option was to reuse the rubble from former buildings to rebuild anew, and a host of new construction techniques were invented to fashion new building materials from old. The Polish word Zgruzowstanie came into use to refer to this post-war innovation in recycling building materials. It was also the name of a recent exhibition at the Museum of Warsaw about the city’s reconstruction, translated into English as Rising from Rubble. The exhibition was curated by architectural historian Adam Przywara, based on his PhD research about the new technological developments that emerged during Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. The most important of these was gruzobeton, or rubble-concrete – a mix of crushed rubble, concrete and water, which was formed into breeze-blocks and became one of the main symbols of post-war Warsaw. Innovative methods were used to reconstitute old bricks and use them in new buildings. Rubble from the former ghetto was formed into building materials and used to build new neighbourhoods. Salvaged architectural details from demolished buildings in the old town were added to the reconstructed facades. Iron was recovered and reused. Mass demolitions even took place in other Polish cities, including Wrocław and Szczecin, to provide more bricks to rebuild Warsaw. Rubble that could not be used in construction was piled up in huge mounds to form geographical features including the Warsaw Uprising Mound, Moczydłowska hill and Szczęśliwicka hill. Although the old town was – remarkably – largely rebuilt by 1955, reconstruction elsewhere in the city lasted until the 1980s, and rubble became a national symbol used by the communist regime to represent the collective effort of reconstruction and a brighter, socialist future. The Rising from Rubble exhibition is more than just a lesson in history. “There are two areas of contemporary relevance: the idea of sustainable architecture, and how it might relate to rebuilding in Ukraine,” Przywara is quoted in The Guardian. Today Warsaw is home to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees and is a key transit point for travel to and from Ukraine. Numerous Ukrainian and European delegations, architects and city planners have passed through and made a point of visiting the exhibition, taking Przywara’s point that the city’s post-war reconstruction could become a blueprint for rebuilding Ukraine’s urban landscapes. The mayor of Mariupol was one such visitor, and the parallels between last year’s Russian air strikes on Mariupol and the bombing of Warsaw nearly 80 years earlier are plain for all to see.  War crimes come in many guises – from the shocking acts of violence in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine in the early weeks of the war to the missile attacks on hospitals and schools, to last month’s destruction of the Kakhovka dam that led to flooding and environmental damage on a colossal scale. But the only war crime that the International Criminal Court (ICC) has so far charged Russian president Vladimir Putin with is the forced abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia. The Financial Times has reported that Saudi Arabia and Turkey are attempting to broker a deal to return thousands of Ukrainian children currently being held in children’s homes in Russia or adopted by Russian families. Nearly 20,000 children have been abducted to Russia, according to Ukrainian sources, although Russia claims the number is far lower. So far about 370 of these children have managed to return to Ukraine, but the process is made painfully difficult. Although Moscow says it will allow children to leave if a legal guardian can collect them, a child’s parent or relative must reclaim them in person and appeal to the local social services for their release. This entails a long and convoluted journey to Russia via Poland and Belarus or the Baltic states, because direct border crossings no longer operate. From Russia, some must continue to Crimea to find their children. But many families whose children have been abducted still live in dangerous regions of Ukraine precisely because they lack the money and passports to enable them to leave, making it harder still for them to make the journey to Russia. In spite of the ICC arrest warrant issued in March against Putin and his children’s rights commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova, the abductions have continued. Some children are taken by pro-Russian relatives or friends, sometimes for financial reasons. Cases have been documented in which foster parents have quickly become abusive once a child is in Russia and used the money they receive for fostering to buy alcohol. Others are kidnapped when their orphanage or boarding school is relocated to Russia from Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine. Many children have been separated from their parents when front lines have shifted while they are away at summer camp, leaving them under Russian occupation, and at risk of relocation to Russia, while their parents remain in Ukrainian-held territory. Earlier in the war, several children whose parents were killed during the siege of Mariupol were forcibly taken to Russia. In addition to the thousands of children abducted to Russia, The Telegraph reported this week that more than 2,000 Ukrainian children have been taken to Belarus since last September on the orders of President Aleksandr Lukashenko. These children are mostly from Russian-occupied areas of Eastern Ukraine. They are taken to Rostov-on-Don, a Russian city some two hours from the border, before being transferred by train to the Belarusian capital Minsk, then bussed to at least four different children’s camps. These camps follow the same pattern as those in Russia. Ukrainian children are subjected to a process of brainwashing to Russify them and eliminate their sense of Ukrainian identity. They sing the Russian national anthem, chant “Down with Ukraine!”, and study lessons according to a Russian curriculum. They learn how Russia is a great country; that the Russian motherland will protect them; that Ukraine has never been a nation and Kyiv will be obliterated. Teenagers are sometimes taken to shooting ranges and taught how to fire machine guns – weapons that they may later use against their fellow Ukrainians. Russia’s brainwashing of Ukrainian children is nothing new. The Ukrainian novelist Victoria Amelina wrote in her essay Expanding the Boundaries of Home: a Story for us All, published by the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in April, about her upbringing as a Russian-speaking Ukrainian in Lviv. “I was born in western Ukraine in 1986, the year the Chornobyl nuclear reactor exploded and the Soviet Union began to crumble. Despite my birthplace and the timing of my birth, I was educated to be Russian. There was an entire system in place that aimed to make me believe that Moscow, not Kyiv, was the center of my universe. I attended a Russian school, performed in a school theater named after the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, and prayed in the Russian Orthodox church. I even enjoyed a summer camp for teenagers in Russia and attended youth gatherings at the Russian cultural center in Lviv, where we sang so-called Russian rock music.” Victoria grew up reading the Russian classics, watching Russian TV, and was chosen to represent Lviv at an international Russian language competition in Moscow at the age of 15. “The Russian Federation invested a lot of money in raising children like us from the "former Soviet republics" as Russians. They probably invested more in us than they did in the education of children in rural Russia: those who were already conquered didn't need to be tempted with summer camps and excursions to the Red Square.” She recounted how a famous Russian journalist interviewed her 15-year-old self for the evening news during her trip to Moscow. After a polite question about her initial impressions, the journalist swiftly switched to grilling her on the oppression of Russian speakers in Ukraine. In a split second, she realised that the entire purpose of the interview was to reinforce a false Russian narrative. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Victoria recalled the story of her trip to Moscow, and her conversation with the Russian journalist, when she watched a TV interview with an older man from Mariupol: “He was desperate, disoriented, and remarkably sincere. "But I believed in this Russian world, can you imagine? All my life I believed we were brothers!" the poor man exclaimed, surrounded by the ruins of his beloved city. It must be way more painful to realize where your true home is in such a cruel way, and so late in life. The man's apartment building was in ruins, and the illusion of home, the space he perceived as his motherland, the former Soviet Union where he was born and lived his best years, had been crushed even more brutally. The propaganda stopped working on him only when the Russian bombs fell.” Victoria Amelina put aside her fiction writing following the Russian invasion and became a war crimes investigator. She travelled to areas of Ukraine that had been liberated from Russian occupation and interviewed witnesses and survivors of Russian atrocities. On her final trip to Eastern Ukraine, Victoria was killed after a missile strike on the pizza restaurant in Krematorsk where she and the group of foreign writers she was accompanying were having dinner. She died on 1 July 2023, aged 37. Click here to read Victoria Amelina’s essay in full. A month has passed since the collapse of the Kakhovka dam in southern Ukraine caused one of the world’s most devastating environmental catastrophes of recent years. The images will live long in the memory – floodwater lapping at the rooftops of Kherson, while civilians attempting to flee their homes in rubber dinghies are targeted by Russian shelling. A video of Ukraine’s chief rabbi, Moshe Reuven Azman, diving for cover as he comes under fire from Russian snipers has been viewed more than a million times. Ukrainian officials say over 100 people died following the dam’s collapse on 6 June as the water hurtled downstream. Today the floodwaters have receded from Kherson and water levels are almost back to normal, but what remains is a sea of mud. Residents have returned and are busy clearing the streets and attempting to renovate their homes, which emit odours of damp and mould. People say they are grateful the disaster happened at the beginning of summer, so that their homes have time to dry out before the winter. The city centre still comes under daily shelling from across the river. The floods are yet another tragedy that the residents of Kherson have had to bear. The city has suffered more than almost anywhere else in the course of 16 months of war – occupied in the early days, the people terrorised and unable to escape, then incessantly bombarded with artillery and rocket fire from across the River Dnieper since the Russian withdrawal last November, deprived of drinking water and electricity. Outside the city, in lower-lying areas below the dam, huge lakes remain in places where there was no water before. The floods destroyed villages, farmland and nature reserves. Crops were lost across vast swathes of farmland as the floodwater raced through, taking with it pollutants including oil and agricultural chemicals, which all gushed into the Black Sea. Further west, residents of Mykolaiv have been warned not to drink tap water, go swimming or catch fish after Cholera-like bacteria were detected in the water. Odesa’s once beautiful coastline has transformed into “a garbage dump and animal cemetery,” according to Ukrainian officials. Of even greater concern are the regions upstream of the dam, where the vast reservoir lies almost empty, changing the entire ecosystem. Half a million people have had their drinking water supply cut off and businesses, agriculture and wildlife have all suffered a massive impact. Covering more than 2,000 square kilometres, the reservoir spanned the Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk districts, and was known by locals as the Kakhovka Sea because it was so big that they could not see the opposite side. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky described the dam’s collapse as “an environmental bomb of mass destruction”. Kyiv and Moscow have blamed each other for the dam’s destruction. Ukraine is investigating the event as a war crime and possible ecocide, and estimates the cost of remedying the destruction at 1.2 billion euros. Preliminary findings from a team of international legal experts working with the Ukrainian prosecutors indicate that it was “highly likely” that the dam’s collapse was triggered by explosives planted by the Russians. Evidence documented by the New York Times also suggests that an explosion in the dam’s concrete base detonated by Russia is the likely cause. The Soviet-era dam has been under Russian control since the early stages of the war last year. Russia’s motivations for such an attack are manifold. Not only would it disrupt and potentially stall Ukraine’s advances and undermine the narrative of its counter-offensive, but also cut hydroelectric power and water supplies, divert resources and potentially help erode the will of the Ukrainian people to resist. But Russia accuses Kyiv of sabotaging the hydroelectric dam to cut off a key water source for Crimea and detract attention from the slow progress of the counter-offensive. Last week, Swedish eco-activist Greta Thunberg was in Ukraine to meet Zelensky and other members of a new environmental group tasked with assessing the environmental damage resulting from the war. She reiterated Ukraine’s use of the word ‘ecocide’ to describe the ecological disaster brought about by the collapse of the dam. But the flooding is not the only environmental impact of the war. About 30 percent of Ukraine’s territory is contaminated with landmines and explosives, and more than 2.4 million hectares of forests have been damaged, Ukraine’s prosecutor general Andriy Kostin says. There has been a long-running battle to get large-scale environmental destruction recognised as an international crime that can be prosecuted at the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the unfolding ecological disaster in Ukraine may bring that a step closer. In 2021 a panel of experts that included the lawyer and author Philippe Sands drafted legislation – yet to be adopted – to enable the ICC to prosecute ecocide, in addition to its existing remit of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. A team from the ICC has visited the area affected by the flooding to investigate. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed