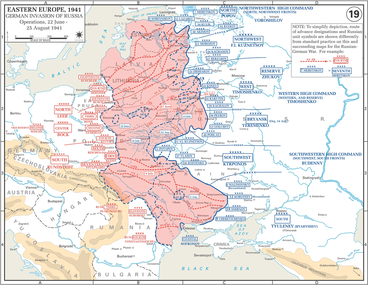

Operation Barbarossa – the German invasion of the Soviet Union – was launched on 22 June 1941. Although the Great Patriotic War, as it is called in Russia, began 81 years ago, and few people who remember it are still alive, the war continues to loom large in the collective consciousness of the former Soviet nations, including both Russia and Ukraine. The fight against fascism was the seminal experience of the Soviet Union’s very existence, and the victory over Nazi Germany, on 9 May 1945, is celebrated as a national holiday with enormous pomp and ceremony – particularly this year, in Russian president Vladimir Putin’s extravagant Victory Day parade. World War Two claimed the lives of up to 27 million Soviet citizens, a death toll that dwarfs that of any other country. The USSR suffered between 9 and 11.5 million military casualties, with possibly another 10 million civilian deaths caused by military activity, and famine or disease claiming a further 8 or 9 million lives. Another 14 million Soviet soldiers were wounded during the war. Among the Soviet Union’s 15 republics, Russia suffered the highest number of casualties, with nearly 7 million military and a similar number of civilian deaths. Ukraine’s death toll was the second highest at more than 1.5 million military deaths and over 5 million from the civilian population. When Germany invaded the USSR, it did so without making any declaration of war, and with a pre-dawn offensive starting at 4am. The parallels with 24 February 2022 are self-evident. In today’s war, both sides accuse each other of being modern-day Nazis. Russia is drawing heavily on its past wartime messages. Once again, its leadership talks of the fight against fascism, about completing the job it started in the 1940s and freeing Ukraine from neo-Nazis. For their part, Ukrainians are making similar analogies. They refer to Putin as ‘Putler’ – an amalgam of Putin and Hitler, calling Russian invaders ‘Russists’ – a combination of Russians and fascists. Making the parallels starker still, the excellent BBC podcast Ukrainecast reported last week that a popular Russian Twitter account that traces events from 81 years ago had been attacked by bots and trolls reacting to words like ‘dictator’ and ‘unprovoked attack’. For Hitler and the USSR, read Putin and Ukraine. The Nazi offensive back in 1941 was a three-pronged attack along a 1,800-mile front. In the north, the German army struck from East Prussia into the Baltic states towards Leningrad. In the centre came an attack pushing northeast to Smolensk and Moscow. And to the south, German troops invaded from southern Poland into Ukraine, heading for Kyiv and from there towards the coast of the Black Sea and Sea of Azov. I have written in my blog before about my own family’s experience in Ukraine during the Second World War – my grandmother’s cousin Moishe from Kyiv, a young Red Army conscript who died on 16 October 1944 near Warsaw, at the tender age of just 18. And another of my grandmother’s cousins, Baya, who was in Kyiv when the Nazis invaded. She and her husband were among a group of Jews forced to board a crowded boat on the River Dnieper, which runs through the centre of the city. The boat was then set alight and everyone on board perished. Other members of my family who lived in the Soviet Union at the time of the German invasion fled to the east, to Uzbekistan. Here the famine and disease that killed so many Soviet citizens during the war were in stark evidence. In the city of Kokand, they survived starvation levels of hunger and epidemics of typhus and other diseases in a city packed to the rafters with evacuees. And now, once again, millions are at risk of famine as a result of war in Europe, as the Russian blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports has trapped more than 20 million tonnes of grain that would normally be exported. The tragedy of the war is already impacting millions of people far beyond the borders of Ukraine, making all our futures more uncertain than ever.

0 Comments

It was revealed this month that Moscow’s chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, is working in exile after coming under pressure from the Russian authorities to support the war in Ukraine. His stance marks a sharp contrast with that of most other religious leaders in Russia. His daughter-in-law, Avital Chizhik-Goldschmidt, tweeted on 7 June that the rabbi and his wife left Russia in March, weeks after the war began, spending time in Hungary and elsewhere in eastern Europe helping fundraising efforts for Ukrainian refugees. His support for victims of the war raised fears for his safety were he to return to Moscow, according to members of the Russian Jewish community quoted in the Israeli media, and friends have advised him against returning to Russia for now. He is currently in Israel, where he is continuing his official duties in exile. As head of the Conference of European Rabbis, Goldschmidt delivered a speech in Munich earlier this month attacking the war. “We have to pray for peace and for the end of this terrible war,” he said. “We have to pray that this war will end soon and not escalate into a nuclear conflict that can destroy humanity.” He was accompanied at the conference by several German bodyguards. Russia's invasion of Ukraine has been “a catastrophe” for Jews, Goldschmidt told delegates. Tens of thousands of Ukrainian Jews – out of a pre-war population of up to 400,000 – have fled the country. “Our colleagues who built up Jewish communities in Ukraine for the last 30 years gave their lives [to that purpose] and they left very comfortable places like the United States and Israel,” he said. And thousands of Jews have also left Russia since the war began, with another “significant part thinking of leaving,” according to Goldschmidt. Born in Switzerland, Goldschmidt had served in Moscow since 1989. He was elected chief rabbi of Moscow, which has a Jewish community of around 100,000, in 1993. He was re-elected to the post after his departure from Russia earlier this year. Other leading rabbis in Russia, in particular the country’s chief rabbi, Berel Lazar, have stayed in the country even after criticising the war. On 2 March, Lazar called for combatants to “silence the guns and to stop the bombs”, and wrote in a statement, “Stop the madness so that no more people die”. Lazar later criticised Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov for his assertion that Adolf Hitler was of Jewish descent – a claim intended to draw an analogy with Ukraine’s Jewish president, Volodymyr Zelensky. But he stopped short of condemning President Vladimir Putin, with whom he is believed to have strong ties. Lazar’s Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia has set itself apart from other religious groups in its open opposition to the war, in particular the Russian Orthodox Church. Its head bishop, Patriarch Kirill, is one of Putin’s most fervent supporters, and has described the Russian dictator’s rule as “a miracle of God”. In early May, Kirill stated that “Russia has never attacked anyone,” and that “we don't want to go to war”. His backing of the invasion has even extended to blessing Russian weapons used in the conflict. In March, hundreds of Russian Orthodox clerics signed a letter protesting at Patriarch Kirill’s backing of the war – at considerable risk to themselves. The EU attempted to add Kirill to its list of sanctioned individuals over his support for the invasion of Ukraine and for acting as a propagandist for Putin’s regime. However objections from Hungary – an EU member state that has good relations with Russia and is heavily reliant on Russian energy imports – resulted in his removal from the list. Several heads of Russian Muslim groups, representing millions of congregants, have also endorsed Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The most vocal among them is the Chechen Muslim leader, Salakh Mezhiyev. Others who have voiced support include Talgat Tadzhuddin, former head of the Central Muslim Spiritual Board of Russia, Ismail Berdiyev, the Muslim leader of the North Caucasus, and Albir Krganov, leader of Russia's Spiritual Board of Muslims. Photo courtesy of kremlin.ru archive (2012) |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed