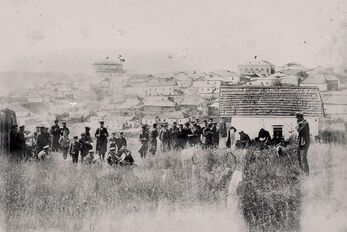

Ukraine doesn’t rank high on the holiday bucket list for most of us right now. But thousands of Hassidic Jews have ignored warnings about travelling to a war zone and flocked to the small town of Uman, some three hours south of Kyiv, for an annual new year pilgrimage. They came to worship at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov who was buried in Uman in 1810. Not all are religious Jews, for according to tradition, the rabbi promised to intercede on behalf of anybody praying at his grave on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. This year around 35,000 pilgrims arrived in Uman (up from the 23,000 who visited last year) in spite of warnings from the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities not to travel because of the risk of Russian air attacks and insufficient bomb shelters for the influx of visitors. Some brought young children with them, believing that a child who visits the grave site before the age of seven will grow up to be without sin. A small number of pilgrims have even been known to bring newborn babies to be circumcised in Uman, in spite of a lack of medical facilities for the procedure in Ukraine. Visitor numbers are only slightly down on the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, even though Uman has been targeted on several occasions. In April more than 20 missiles struck the town killing 24 people including several children in a residential district. It last came under Russian missile attack in June. The front line lies around 200 miles to the south. “It is very dangerous. People need to know that they are putting themselves at risk. Too much Jewish blood has already been spilled in Europe. How can you take such a risk?” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this month. With Ukrainian airspace closed, the journey to Uman is long, costly and uncomfortable, involving a flight to Poland, trains, minivan taxis and an inevitable long wait at the border. But the pilgrims remain undeterred in spite of the danger, expense and logistics of holidaying in a war zone. Some are firm in the belief that their Rabbi will protect them from beyond the grave; others just come to party and have a good time. Most come from Israel and spend up to a week in Uman around Rosh Hashanah. Although women are allowed on the pilgrimage, the vast majority of the visitors are men. The annual Jewish gathering has become the town’s major source of income, with pilgrims charged a $200 fee to visit. In recent years, the rabbi’s grave has been renovated with funds donated by Jewish tycoons from around the world. Hotels and hostels have popped up and locals have carried out house renovations to provide accommodation priced at hundreds of dollars a night. Those who can’t afford the exorbitant room prices pitch tents in courtyards or vacant lots. A whole hospitality industry has built up around the pilgrims, offering kosher food and drink at vastly inflated prices, using Hebrew signage and accepting payment in dollars or Israeli shekels. Most of the business owners are Israelis. Dozens of Israeli families moved to Uman in the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The annual influx of bearded, black-robed, skull-capped men makes quite an impact in this quiet town. While the visitors provide Uman with much-needed cash, relations between the pilgrims and the townsfolk are not always harmonious. Locals complain about the loud music, drunkenness, fighting and excessive litter. They resent the police cordons and checkpoints that prevent them from going about their daily business; and they question how the authorities are spending the money collected from the pilgrims, citing widespread corruption. Imagine a massive rave – albeit a religious one – taking over the streets of a small, unexceptional town and you start to get the picture. The Hassidic music blasting from speakers in the streets is imbued with a techno twist. Alcohol and drugs are much in evidence, as is prostitution. It’s hard to put a number on the percentage who come to celebrate and party, not just to pray. There’s a heavy security presence, even in peacetime, but it was stepped up this year in light of the added dangers of war. Police numbers have increased since 2010, when a young Israeli was stabbed in a brawl and ten pilgrims were deported after violent clashes broke out. Violence in Uman is nothing new. In 1941, under German occupation, the Nazis murdered 17,000 Jews here and destroyed the Jewish cemetery, including the grave of Rabbi Nachman, which was later located and moved before the area was redeveloped for housing. The original burial site was close to a mass grave for victims of another Jewish massacre, one that took place in 1768 as part of the Haidamak uprisings. The Uman pilgrimage began shortly after the rabbi’s death in the early 19th century and attracted hundreds of Hassidic Jews from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland until the Russian Revolution of 1917 closed the borders. The photo below dates from this period. In spite of the Communist regime’s clampdown on religious practice, a trickle of pilgrims continued to visit the grave site, including some Soviet Jews who made the journey in secret and were exiled to Siberia as a consequence. From the 1960s, small numbers of American and Israeli Jews travelled to Uman either legally or clandestinely. In the late 1980s, travel to the Soviet Union became easier and the number of pilgrims began to grow. Around 2,000 made the journey to Uman in 1990, rising to 25,000 by 2018.

0 Comments

Warsaw is possibly the most fascinating city I have ever visited. Its glorious old market square, lined with Baroque-style merchants’ houses, rivals those of Krakow, Prague or Brussels. And yet Warsaw’s old town was reconstructed from scratch in the middle of the twentieth century. Somehow the knowledge that the colourful facades are mere decades rather than centuries old added to my appreciation of them – each one painstakingly rebuilt using 18th century paintings of the city by the Venetian artist Bernardo Bellotto as a blueprint. That this reconstruction was carried out during a period when Stalinist architecture dominated in the Soviet bloc makes it doubly remarkable. The rebuilding of Warsaw itself could, in the coming years, serve as a blueprint of another kind – as a route-map for the reconstruction of Ukrainian towns and cities after months of Russian aerial bombardment. While much of Europe experienced destruction on a monumental scale during World War II, the fate of the Polish capital was uniquely cruel. Most of the city was razed to the ground in retribution for the failed Warsaw Uprising of August-September 1944, when the Polish resistance attempted to liberate the city from Nazi occupation. Despite being poorly equipped, the Poles succeeded in killing or wounding several thousand German fighters in a battle lasting for two months, but at a terrible cost. Up to 200,000 Polish civilians were killed, mostly in mass executions, and once the Germans had quelled the uprising, they systematically destroyed what remained of the city, reducing more than 85% of its historic old town to ruins. Today we can only imagine how daunting the task of reconstruction must have seemed. Indeed, some suggested at the time that what remained of Warsaw should be left as a memorial and the capital relocated elsewhere. Many residents and refugees, who returned once Soviet and Allied forces reoccupied the ruined city, were formed into work brigades tasked with clearing the vast amounts of debris, as were German prisoners of war. It was estimated that the sheer volume of rubble – around 22 million cubic metres of the stuff covering almost the entire city – meant that it would take 20 years to transport it out of the city by daily goods trains. Amid the post-war scarcity, Poland lacked the financial resources to purchase construction materials. And the hundreds of brickworks that had flourished in Warsaw before the war – many of them owned by Jews – no longer existed. If the city was to rise from the ashes, the only option was to reuse the rubble from former buildings to rebuild anew, and a host of new construction techniques were invented to fashion new building materials from old. The Polish word Zgruzowstanie came into use to refer to this post-war innovation in recycling building materials. It was also the name of a recent exhibition at the Museum of Warsaw about the city’s reconstruction, translated into English as Rising from Rubble. The exhibition was curated by architectural historian Adam Przywara, based on his PhD research about the new technological developments that emerged during Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. The most important of these was gruzobeton, or rubble-concrete – a mix of crushed rubble, concrete and water, which was formed into breeze-blocks and became one of the main symbols of post-war Warsaw. Innovative methods were used to reconstitute old bricks and use them in new buildings. Rubble from the former ghetto was formed into building materials and used to build new neighbourhoods. Salvaged architectural details from demolished buildings in the old town were added to the reconstructed facades. Iron was recovered and reused. Mass demolitions even took place in other Polish cities, including Wrocław and Szczecin, to provide more bricks to rebuild Warsaw. Rubble that could not be used in construction was piled up in huge mounds to form geographical features including the Warsaw Uprising Mound, Moczydłowska hill and Szczęśliwicka hill. Although the old town was – remarkably – largely rebuilt by 1955, reconstruction elsewhere in the city lasted until the 1980s, and rubble became a national symbol used by the communist regime to represent the collective effort of reconstruction and a brighter, socialist future. The Rising from Rubble exhibition is more than just a lesson in history. “There are two areas of contemporary relevance: the idea of sustainable architecture, and how it might relate to rebuilding in Ukraine,” Przywara is quoted in The Guardian. Today Warsaw is home to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees and is a key transit point for travel to and from Ukraine. Numerous Ukrainian and European delegations, architects and city planners have passed through and made a point of visiting the exhibition, taking Przywara’s point that the city’s post-war reconstruction could become a blueprint for rebuilding Ukraine’s urban landscapes. The mayor of Mariupol was one such visitor, and the parallels between last year’s Russian air strikes on Mariupol and the bombing of Warsaw nearly 80 years earlier are plain for all to see. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed