Every day this month, Holocaust survivors from around the world are posting videos of themselves reading from Holocaust denial articles found on social media as part of a campaign titled #CancelHate organised by the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. The Claims Conference, as it is better known, launched the project to illustrate how Holocaust denial and distortion can not only rewrite history, but perpetuate antisemitic tropes and spread hate. It comes at a time of rising antisemitism around the world, triggered by Israel’s horrific military campaign in Gaza in response to the deadly Hamas attack of 7 October. “The world is a volatile place right now. Social media offers individuals a place to hide while they spread words of hate. This campaign shows that these are not victimless posts – these mean and vile words deny the first-hand testimony of each and every Holocaust survivor, their suffering and the suffering and often loss of their families,” says Gideon Taylor, President of the Claims Conference. Recent studies conducted by the Claims Conference show a growing gap in basic knowledge of the Holocaust, leaving younger generations increasingly vulnerable to denial and distortion. An astonishing 49% of young American adults have come across information online denying or distorting the truth about the Holocaust. Elsewhere, in the UK, 29% of adults reported seeing denial or distortion on social media. In Canada, 22% of Millennial and Gen Z adults were not even sure if they had heard of the Holocaust. Meanwhile, in Russia, President Vladimir Putin’s government repeatedly manipulates the history of the Holocaust for its own political purposes, falsely portraying Ukrainians as Nazis and even accusing Jews of being Nazis. “I could never have imagined a day when Holocaust survivors would be confronting such a tremendous wave of Holocaust denial and distortion, but sadly, that day is here. We all saw what unchecked hatred led to – words of hate and antisemitism led to deportations, gas chambers and crematoria. Holocaust survivors from around the world are participating in this campaign to show that hate will not win,” says Greg Schneider, Executive Vice President of the Claims Conference. With the last generation of Holocaust survivors now in their eighties and nineties, the number of survivors able to tell their stories dwindles year by year and it will soon be too late to hear their testimonies direct. Listening to these old men and women recounting brief snippets about events that happened to them as young children, the power of their words is still strong, their emotion palpable. Each video shows a Holocaust survivor introducing themselves, reading social media posts about Holocaust denial, then briefly recounting some of their own experiences of the Holocaust. Every video ends with the tagline, “Words matter. Cancel hate”. Here’s an example, presented by a Jewish American therapist, social worker, author and academic, who was born in Poland: “My name is Tova Friedman, I am a holocaust survivor. Let me read to you words of a denier: ‘Dachau was full of Catholic religious and priests, not Jews. Auschwitz Jews had swimming pools, orchestras, and brothels.’ These are the words of a denier. Well, let me tell you, at the age of 5½, I and my mother and father got off the cattle trucks in Auschwitz. I was taken away from my mother and I spent six months of my life with inhuman conditions – starvation, illnesses. I saw the death chambers, I saw the smoke. We were tattooed. There were so many incidents – beatings, starvation, typhus. Out of my town, out of hundreds of children, five were left. Words matter. Cancel Hate.” Abraham Foxman, an American lawyer and former national director of the Anti-Defamation League, says, “I survived the Holocaust, but 13 members of my immediate family were murdered because they were Jewish. Holocaust denial on social media isn’t just another post. These things we say matter. Posts that deny the Holocaust are hateful and deny the suffering of millions of people. We must take our words seriously. Our words matter.” Hedi Argent MBE, a 94-year-old British author, fled her home in Austria with her family in 1939, just weeks before the border closed. “My family was turned out of our home…because we were Jews. My father was forced to scrub the streets and was later arrested for making anti-Nazi comments, yet we were the lucky ones. The 17 members of my family who were murdered were not lucky. The Holocaust did happen,” she recounts. Herbert Rubinstein was five years old when he and his mother were taken from the Jewish ghetto in Chernivtsi and herded onto a cattle truck bound for the camps. They were among the few lucky ones – having managed to obtain forged Polish identity documents while living in the ghetto, they were removed from the truck and fled, seeking refuge in several countries of Eastern Europe until the end of the war. “I lived through the Holocaust. Six million were murdered. Hate and Holocaust denial have returned to our society today. I am very, very sad about this and I am fighting it with all my might and strength. Words matter. Our words are our power,” he says. Watch the videos here https://www.claimscon.org/cancelhate/ or follow the Claims Conference on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ClaimsConference

0 Comments

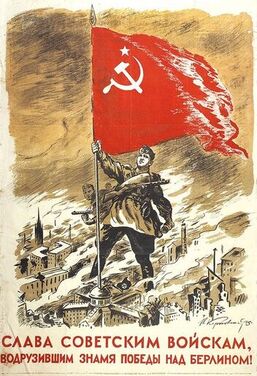

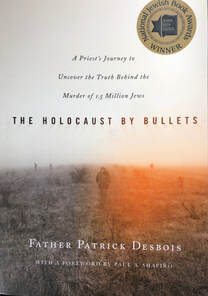

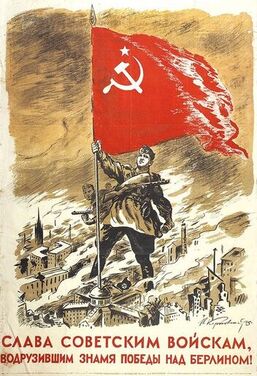

Eighty years ago, the biggest Jewish revolt against Nazi aggression was under way. The Warsaw ghetto uprising, which lasted from 19 April-16 May 1943, was an attempt to prevent the deportation of the remaining population of the ghetto to the gas chambers. The previous summer, more than a quarter of a million Jews had been transported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Foreseeing their own fate, the remaining residents developed resistance movements, smuggled weapons into the ghetto and prepared to fight. They knew that victory was impossible; they fought instead for the honour of the Jewish people, and to prevent the Germans from choosing the time and place of their deaths. On 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover, Germans entering the ghetto to begin the deportation were met by gunfire, grenades and Molotov cocktails. Pitched battles raged for days, until the Germans resorted to burning down the ghetto, block by block. Thousands of Jews took refuge in sewers and bunkers, which the Nazis then destroyed. The uprising came to an end on 16 May 1943. Around 13,000 Jews had died, and a further 55,000 were captured and taken to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek. The presidents of Germany, Poland and Israel gathered on 19 April at a memorial on the site of the former ghetto to mark the 80th anniversary of the uprising. “I stand before you today and ask for forgiveness,” German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier said. “The appalling crimes that Germans committed here fill me with deep shame… You in Poland, you in Israel, you know from your history that freedom and independence must be fought for and defended, but we Germans have also learned the lessons of our history. ‘Never again’ means that there must be no criminal war of aggression like Russia’s against Ukraine in Europe.” A 96-year-old Polish Holocaust survivor, Marian Turski, warned against apathy in the face of rising hatred and violence. “Can I be indifferent, can I remain silent, when today the Russian army is attacking our neighbour and seizing its land?” he questioned. The anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising comes as Russia is preparing to commemorate its own wartime anniversary – that of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. The Kremlin continues to draw parallels between the Second World War and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that Russia is fighting Nazis and battling for its survival against an aggressive force from the West that his hellbent on its annihilation. Russia’s motivation for its war in Ukraine is to ensure that “there is no place in the world for butchers, murderers and Nazis,” Putin said last year. “Victory will be ours, like in 1945.” But Victory Day, celebrated in lavish style on 9 May every year in Russia, will entail less pomp and ceremony than usual. Several cities are scaling back their celebrations for security reasons, fearing attacks by pro-Ukrainian forces following a spate of explosions and fires in recent days involving Russian energy, logistics and military facilities. The reduced scale of events also signals a degree of nervousness that the parades could become an outlet for disaffection with the war in Ukraine. Most notably, Immortal Regiment processions, which take place in all major towns and cities across Russia, have been cancelled this year. During the parades, hundreds of thousands of people march carrying photographs of relatives who fought or died during World War II. Putin himself attended an Immortal Regiment march in Moscow last year, holding a portrait of his father. The procession is a key event in the glorification of Russian sacrifice in the defeat of Nazi Germany – a cornerstone of Russia’s nationalist resurgence during Putin’s two decades in power. Ostensibly called off because of fears of a terrorist attack, Immortal Regiment processions risk highlighting the human cost of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The Kremlin fears that thousands of Russians would march with photographs of family members killed in the current war, bringing into sharp focus Russia’s mounting losses, and potentially risking the morphing of processions into protest events. The Russian authorities remain tight-lipped about the scale of the country’s losses in Ukraine. The most recent update came back in September, when the military reported that nearly 6,000 Russian soldiers had lost their lives. The US estimates Russian casualties in Ukraine to amount to over 200,000 dead or wounded. During last year’s Victory Day celebrations, 125 people were detained for protesting about the war, many of them at Immortal Regiment parades. Last Friday, 27 January, was Holocaust Remembrance Day, marking the 78th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz by Soviet troops on that day in 1945. The sombre anniversary was commemorated across Europe in many different ways. Most movingly, in Kyiv, the choir of the Ukrainian armed forces performed a haunting song called Eli Eli (my God, my God) in a ceremony at Babi Yar – the ravine on the outskirts of Kyiv where more than 33,000 Jews were shot after Nazi troops invaded Soviet Ukraine in 1941. The song was written by Hannah Szenes, a Jewish poet living in Palestine, who volunteered to join the British forces during World War II. She and her unit were dispatched to Croatia and joined a local partisan unit in 1944. Attempting to enter Hungary to save her mother, who was at the time still living in Budapest, she was captured and later executed by the Nazis. Before leaving on her mission, Szenes had entrusted a notebook to a friend, which included Eli Eli, a song that she had written in 1942. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky attended the ceremony. Zelensky’s own great-grandparents died when the Nazis burned down their village, and his grandfather was the only one of four brothers to survive the war as a Red Army soldier. In a video statement to mark Remembrance Day, Zelensky called on the world to “overcome indifference”. “We know and remember that indifference kills along with hatred. Indifference and hatred are always capable of creating evil together,” he said. “That is why it is so important that everyone who values life should show determination when it comes to saving those whom hatred seeks to destroy. “Today, we repeat it even more strongly than before: never again to hatred; never again to indifference. The more nations of the world overcome indifference, the less space there will be in the world for hatred.” Other Ukrainian government officials were more direct in their condemnation of today’s war. A leading presidential advisor, Andriy Yermak, wrote on Twitter that the Holocaust “should have served as a warning to prevent new crimes against humanity. But today, in the very centre of Europe, a genocide of Ukrainians is occurring. We will neither forgive nor forget anything.” Meanwhile, Russian president Vladimir Putin took advantage of Holocaust Remembrance Day to reiterate his phoney claims justifying the invasion of Ukraine. "Forgetting the lessons of history leads to the repetition of terrible tragedies," he said. "This is evidenced by the crimes against civilians, ethnic cleansing and punitive actions organised by neo-Nazis in Ukraine. It is against that evil that our soldiers are bravely fighting." At the same time, the Kremlin continued its attacks on independent news media reporting on the war, branding the popular news site Meduza as undesirable. The designation means that anyone who aids or promotes Meduza – by speaking to its journalists (based in Latvia), or even sharing or liking its content – could face prosecution. By silencing independent media, Putin hopes to drown out all opposition to his own war propaganda, which is trotted out on state television and in the Russian press. In Poland, around 185 miles from the Ukrainian border, survivors of Auschwitz-Birkenau and other mourners gathered at the site of the Nazi concentration camp to commemorate the anniversary of its liberation. “Standing here today at the Birkenau memorial site, I am horrified to hear the news from the east. That there is a war there, that the Russian troops that liberated us here are waging a war in Ukraine. Why? Why is there such a policy?” Auschwitz survivor Zdzislawa Wlodarczyk said. The director of the Auschwitz museum, Piotr Cywinski, echoed President Zelensky’s call to overcome indifference. “Being silent means giving voice to the perpetrators. Remaining indifferent is tantamount to condoning murder,” he said, comparing Russian war crimes in towns such as Bucha and Mariupol with Nazi atrocities. Rabbi Refael Kruskal, vice-president of Odesa’s Jewish community and the son of a survivor of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, has helped evacuate over 4,000 people from Odesa. The city had a Jewish population of around 45,000 before the Russian invasion. “People always say never again, never again, but this year it is actually happening again,” he told France-based Euronews. “I never had to run away from Ukrainians, but I helped my entire community flee Ukraine because of Russian bombs.” The images circulating in recent days of joyful Ukrainians celebrating the Russian retreat from Kherson tell a rare story of hope amid the devastation of war. Kherson was captured in early March, just days into the Russian invasion, and since then had remained the only Ukrainian regional capital under Russian occupation. For Moscow, the Kherson region provided a foothold west of the Dnieper river, a tactical location to facilitate a Russian push further west – to Odesa, seen as one of the most valuable prizes for Russian president Vladimir Putin. As well as being a key strategic port on the Black Sea, Odesa was known as the jewel in the crown of the Russian Empire, so called for its glorious situation, architecture and cultural heritage. Just a few short weeks ago, Putin announced with great fanfare that Russia had annexed the whole of the Kherson region – together with the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia – and that it would remain Russian forever. Moscow still claims this to be the case, but its words now ring hollower than ever. The liberation of Kherson feels like a watershed moment in the conflict, and it is little surprise that some have made historical comparisons with Stalingrad – the most crucial turning point of World War II. This brutal battle was fought from August 1942-February 1943 and finally resulted in a Soviet victory, triggering the German retreat from the Soviet Union. “After Kherson, it will be the turn of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, then Crimea. Or Crimea could be first, followed by Donbas, depending on how the situation plays out on the battlefield,” Roman Rukomeda, a Ukrainian political analyst, optimistically predicts. Whether the Russian retreat from Kherson indeed turns out to be a pivotal event in the Ukraine war remains to be seen. Kyiv remains wary of a Russian trap or ambush and consolidation of Russian positions east of the Dnieper raise fears of another bombing campaign. The recent heart-breaking BBC documentary Mariupol: The People’s Story offers a terrible reminder of the utter devastation that city and its population suffered under Russian bombardment earlier this year… …Which brings me to another World War II comparison from the same part of the world. SHTTL is a new film showing at the UK Jewish Film Festival this week, set in a Ukrainian shtetl near Ternopil close to the Polish border on the eve of the Nazi invasion in June 1941. Like the scenes in the BBC documentary of Mariupol and its inhabitants before the Russian invasion, the film depicts a location and way of life that is on the verge of vanishing completely. Its title, SHTTL, purposefully drops the letter ‘e’ to symbolise the disappearance of Jewish shtetl life and acts as a tribute to those who lived there. The action centres on Mendele, a young man returning to the shtetl to get married having left for Kyiv to pursue a career as a filmmaker. It follows his interactions with friends, family members and neighbours; their debates, discussions and arguments. Only the viewer knows, of course, that the wedding will never take place; that the community is about to be destroyed, its residents shot and buried in shallow pits. This is a Holocaust film with a difference, for rather than depicting death and suffering, it depicts life, with its diverse mix of joy and sorrow and disappointment. Written and directed by Ady Walter, and with dialogue entirely in Yiddish, SHTTL was filmed in a purpose-built village 60 kilometres north of Kyiv. The set includes a reconstruction of the only remaining wooden synagogue in Europe, which was blessed and consecrated to enable it to hold real-life prayer services. Household items from the 1940s were sourced from all over Ukraine. The village was intended to be transformed into an open-air museum to educate local schoolchildren and help Ukrainians to better understand their Jewish history and culture. The area north of Kyiv, of course, was under Russian occupation in the early weeks of the current war. The utter devastation wreaked by the Russian troops and their complete disdain for human life, as witnessed in Bucha, Irpin and elsewhere, leaves the museum project up in the air. “We don’t know what’s happened to it now,” Walter told the The New European. “We know it became a minefield around there and that there was heavy fighting, but we have no idea what has become of the construction.” Mariupol: The People’s Story is on BBC iPlayer in the UK and will be available on other BBC platforms for viewers elsewhere. SHTTL will be screened in London at the UK Jewish Film Festival at 6pm on Thursday 17 November. It is not yet on general release. A tour of the film set is available on YouTube:  Ever more shocking documentary evidence continues to emerge of Russian atrocities in Bucha, 30 kilometres northwest of Kyiv. The horrors started to come to light in early April after the town’s liberation by Ukrainian forces. According to the latest reports by the BBC, around a thousand bodies have been recovered from Bucha, following nearly a month of occupation by Russian troops, including 31 children. Of these, more than 650 had been shot. The New York Times last week revealed video footage taken on 4 March, showing a group of nine Ukrainian captives being led at gunpoint by Russian troops. They walked in single file, their backs hunched, each holding onto the clothing of the man in front. At the front and back of the line of captives was a Russian soldier with a gun. They led the men behind an office building. Witnesses heard the gunshots, and drone footage shows dead bodies beside the building, with Russian soldiers standing over them. And the BBC reported the chilling signs of a massacre in a children’s holiday camp on the edge of woodland in Bucha. Promenystyi, or Camp Radiant, is decorated with mosaics showing happy children against a background of rays of bright sunshine. A basement at the camp was transformed into a torture chamber, where five men were found crouching on their knees, heads down and hands bound behind their backs. They had been tortured and shot. More than a dozen bullet holes were visible in the walls, surrounded by patches of dried blood. This wasn’t the first time that the basement of a holiday camp had been used as a torture chamber. In nearby Zabuchchya, Ukrainian forces in early April discovered eighteen burnt and mutilated bodies of men, women and children, some with ears cut off, others with teeth pulled out, and many with their hands tied behind their backs. Girls as young as fourteen had been raped by Russian soldiers. The Russian authorities have repeatedly denied responsibility for the massacre of civilians in Bucha and elsewhere. They have claimed that the reports were staged or faked, as a provocation by Ukraine. That these horrors are taking place in Europe, in 2022, is hard to fathom. These very same towns and villages were the scene of some of the most terrible atrocities of World War II, events that brought the international community together to declare “Never Again” - an avowal that has been breached all too many times. I have just finished reading a book of witness accounts of the mass killings of Jews in Ukraine in 1941-44. Father Patrick Desbois, a French priest, spent several years in the early 2000s travelling around the small towns and villages of rural Ukraine seeking out and interviewing hundreds of elderly people who, as children sixty years earlier, had seen, heard or even participated in, the Holocaust by Bullets, in which 1.5 million people were executed. These were the earliest mass victims of the Holocaust. They were not transported in cattle trucks to concentration camps, but taken on foot, on peasant carts, or in German military trucks, to sites often in or near woodland, just outside the towns and villages where they lived. Here they were shot in large pits or ditches, that they were often forced to dig themselves. They were shot at close range, sometimes face-to-face, but more often in the back. They were murdered in the presence of local residents. Their non-Jewish neighbours, even friends, or school classmates. Together with an international group of researchers, interpreters, photographers and even a ballistics expert, Father Desbois used forensic evidence, eyewitness accounts and archival material to uncover the burial sites and the brutal stories behind them. His book provides a definitive and harrowing account of a rarely explored chapter in the story of the Holocaust. I have read and written so much about the Holocaust and the earlier pogroms against the Jews in Ukraine, that I am not easily shocked by accounts of extreme violence. But both the reports of atrocities in Bucha, and the witness interviews conducted by Father Desbois, are agonising to read and have shaken me to the core. That such horrific crimes as those perpetrated in Ukraine again and again in 1941-44 could be repeated now, in 2022, is utterly beyond belief.  Victory Day, on 9 May, is the most solemn and serious of national celebrations in Russia. On this date thirty years ago, I was in the southern Russian city of Voronezh. It was a beautiful, sunny day, the warmest of the year so far after a long, bleak winter. The main street was closed to traffic and it seemed the whole population of the city was outdoors. But the glorious holiday weather didn’t prompt people to shed layers of clothing and relax with picnics and drinks in the city’s parks as they might have elsewhere. Instead, families walked, silent and sombre, towards the war memorial to lay flowers, three or four generations together. The older men wore rows of medals with multi-coloured ribbons attached to their jackets. Many were dressed in military uniform. The women were togged up in their Sunday best. Children were primped and preened with oversize bows for the girls and buckles and braces for the boys. Although the holiday celebrated the victory of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is known – there was no sense of jubilation. The Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the victory and the war took a terrible toll. An estimated 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Every family lost a son, a brother, a father, an uncle or a cousin. The pomp and ceremony of today’s Victory Day parade in Moscow add some glitz and glamour that didn’t exist in the immediate post-Soviet era. And of course, the war in Ukraine adds poignance to the occasion. It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin in his Victory Day speech linked the current conflict with the triumph over Nazi Germany. Time and again, he has drawn parallels between the two wars, starting with his bizarre notion of the need for Russia to rid Ukraine of Nazis. Given the Jewish origins of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, the Nazi tag has struggled to stick. But Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comparison of Zelensky with Adolf Hitler, in an attempt to legitimise Russia’s goal of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, took the analogy up a notch. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst anti-Semites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood – statements that typify the distortion of history that underpin Russia’s war with Ukraine. The question of Hitler’s Jewish identity is nothing new – and remains unproven. The issue centres on Hitler’s father, born in Graz, Austria, in 1837 to an unmarried mother. Speculation over who the child’s father was has continued for decades, fuelled by the fact that following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the records of his grandmother’s community to be destroyed. A memoir by Hans Frank, head of Poland’s Nazi government during the war, claimed that the son of Hitler’s half-brother tried to blackmail the Nazi dictator, threatening to expose his Jewish roots. Following worldwide outrage over Lavrov’s comments, and in particular heated condemnation from Israel, the Russian president was forced to issue a rare apology to his Israeli counterpart, Naftali Bennett, rather than risk alienating a country that has been more supportive than most. Israel has been an ally of Russia since the end of the Soviet Union – based in part on both countries’ military interests in Syria and the substantial Russian-Jewish population in Israel – and has faced criticism for failing to join Western sanctions. Israeli foreign minister Yair Lapid said Lavrov’s comments “crossed a line” and condemned his claims as inexcusable and historically erroneous, while Dani Dayan, head of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem, denounced them as “absurd, delusional, dangerous and deserving of condemnation”. Russia’s foreign ministry hit back, accusing the Israeli government of supporting a neo-Nazi regime in Kyiv. Only time will tell if the war of words leads to firmer Israeli support for Ukraine. Russian TV host Vladimir Solovyov last week pushed the Nazi narrative further, clarifying a new definition of Nazism to explain the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. “Nazism doesn’t necessarily mean anti-Semitism, as the Americans keep concocting. It can be anti-Slavic, anti-Russian,” he said. To keep its phoney narrative alive, Russia will keep churning out the rhetoric on Nazism in the hope that if it repeats it often enough and loudly enough, more people will believe it. But the longer Putin’s Russia continues murdering Ukrainian citizens and bombarding Ukrainian cities, the more it resembles Hitler’s Nazi regime.  This year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day falls today, 28 April. Yom HaShoah is a national holiday in Israel held on or just before the 27the day of Nisan in the Hebrew calendar. The date marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, when Jewish resistance fighters attempted to halt the Nazis’ final effort to transport the city’s remaining Jews to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek, the largest single revolt by Jews during World War II. Further east, in Soviet Ukraine, the Holocaust took a different form. Rather than ghettos and concentration camps, the Nazis used bullets and executions in mass graves on the outskirts of towns and villages. Vanda Semyonovna Obiedkova lived in Zhdanov, a city in eastern Ukraine named after the Soviet politician Andrei Zhdanov. Ten-year-old Vanda hid in a basement when the SS came to take away her mother after the Germans invaded in October 1941. On 20 October 1941, the Nazis executed up to 16,000 Jews in pits dug on the outskirts of the city, including Vanda’s mother and all her mother’s family. The SS later found Vanda and detained her, but family friends were able to convince them that the little girl was Greek, rather than Jewish. Her father, a non-Jew, managed to get her admitted to a hospital, where she remained until the liberation of Zhdanov in 1943. Today Zhdanov is known as Mariupol. In a haunting echo of her escape from the Nazis more than 80 years ago, 91-year-old Vanda was forced once again to hide in a basement when the Russian army began bombing the city in early March. She died there on 4 April. “There was no water, no electricity, no heat — and it was unbearably cold,” her daughter Larissa told Dovid Margolin in an interview with Chabad.org. Although Larissa tried to care for her mother, “there was nothing we could do for her. We were living like animals,” she said. It was too dangerous even to go out to find water as two snipers had set up positions near the closest water supply. “Every time a bomb fell, the entire building shook,” Larissa said. “My mother kept saying she didn’t remember anything like this during World War II… Mama didn’t deserve such a death”. In her final two weeks, Vanda was no longer able to stand. She lay freezing and pleading for water, asking, “Why is this happening?”. Larissa and her husband dodged the shelling to bury her in a public park near the Sea of Azov. “Mama loved Mariupol; she never wanted to leave,” she said. Vanda gave an interview to the USC Shoah Foundation in 1998, documenting her life story and Holocaust experience. “We had a VHS tape of her interview at home,” Larissa said, “but that’s all burned, together with our home.” In 2014, when fighting broke out in Mariupol as Russian separatists threatened to take the city, Larissa and her family – along with many of the city’s Jews – were evacuated to Zhitomir, in the west of the country, with the help of Rabbi Mendel Cohen, the city’s only rabbi and director of Chabad-Lubavitch in Mariupol. The family returned after Ukrainian troops secured the city, but Larissa said there’s no going back this time. She and her family were evacuated by Rabbi Cohen for a second time after her mother’s death. “I’m so sorry for the people of Mariupol. There’s no city, no work, no home — nothing. What is there to return to? For what? It’s all gone. Our parents wanted us to live better than they did, but here we are repeating their lives again,” she said. Vanda is the second Holocaust survivor known to have died in the war in Ukraine, after 96-year-old Boris Romanchenko, who was killed during a Russian attack on Kharkiv. He survived the Nazi concentration camps of Buchenwald and Bergen Belsen. The full interview is available here Photo of Vanda and her parents published with permission of Chabad.org  Ukraine has been in this horrifying situation before. Last time, in 1941, it was the Nazis who invaded, and this time it is the Russians – fellow countrymen back in the days of the Soviet Union – on a bizarre pretext of denazification. To add to the irony, many Jewish Ukrainians who survived the Holocaust of the early 1940s have found refuge from the latest war in – of all places – Germany. The horrors of World War II will soon drop out of living memory, but they have not done so yet, and for elderly Ukrainians who remember the German occupation, lightning is striking twice. In an interview with The Associated Press, Tatyana Zhuravliova, an 83-year-old Ukrainian Jew, recalled the moment when, as a little girl, she hid under a table to save herself from the Nazi bombing of Odesa, her childhood home. She fled to Kazakhstan to escape the massacre of tens of thousands of Jews in Odesa and later settled in Kyiv. The same panic gripped her when the Russian air strikes on Kyiv began in February. Now Zhuravliova has found safety in Germany, the old enemy. She was part of a first group of Holocaust survivors evacuated to Frankfurt by the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. The group, also referred to as the Claims Conference, represents Jews in negotiating for compensation and restitution for victims of Nazi persecution, and provides welfare for Holocaust survivors worldwide. Transporting the elderly, many of whom are very frail, out of a warzone is fraught with difficulties, not least constant shelling and artillery fire. It involves finding medical staff and ambulances in numerous battle grounds, crossing international borders and even convincing survivors, who are ill and unable to leave their homes without help, to flee into uncertainty again, this time without the vigour of youth. But the risks of staying behind are also high, as the death of 96-year-old Boris Romanchenko shows. Having survived the Nazi concentration camps, he was killed during an attack on Kharkiv. Once in Germany, the elderly refugees are being settled into nursing homes and the government has offered them – along with several thousand other Ukrainian Jews who have fled the war – a path to permanent residence as part of Germany’s efforts to compensate Jews since the Holocaust. Another Holocaust survivor recently arrived in Frankfurt, 83-year-old retired engineer Larisa Dzuenko, recalled, “When I was a little girl, I had to flee from the Germans with my mom to Uzbekistan, where we had nothing to eat and I was so scared of all those big rats there. All my life I thought the Germans were evil, but now they were the first ones to reach out to us and rescue us.” Yuri Parfenov is another survivor of the 1941 massacre of Odesa’s Jewish population. He hid with his brother in a toilet pit when the soldiers came for them, but his mother and 13 other members of his family were among the tens of thousands of Odessan Jews murdered by Romanian soldiers allied with Nazi Germany, he tells The Independent. Parfenov, who is half-Russian, went on to serve as a tank captain in the Soviet army. Today he is under threat from a Russian invasion aimed at saving Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population from a supposed genocide. “Tell Putin: who are you liberating us from?” he says in Russian – his native language, comparing Vladimir Putin to Adolf Hitler. Parfenov is one of dozens of Holocaust survivors still living in Odesa, which is home to a large Russian-speaking community. In the 1930s around 200,000 Jews lived in the city, making up a third of the population. Around half managed to escape to the east before Hitler’s Romanian allies occupied the city, murdering more than 25,000 Jews and deporting another 60,000, most of whom perished in camps and ghettos. “We are a generation of people who lost their childhood. I do not worry about myself, I worry about the next generation,” says 88-year old Holocaust survivor Roman Shvarcman in the same article in The Independent. “When the air raid sirens scream, I try to make it to the basement of my 10-storey building, and I sit in the cold and pray that my grandchildren, my great grandchildren, will have a bright and happy youth…I can’t hold a rifle, I am not a fighter and I am too old, but my weapon is my words against this Russian fascism. It is my weapon to fight,” he says. His stories of World War II feel horribly familiar in the current conflict. Shvarcman’s family, originally from Vinnytsia, 250 miles north of Odesa, fled in a convoy of civilians under repeated heavy bombing before eventually being stopped by German soldiers and forced to turn around. His family was starved, his sister raped by Romanian soldiers, and his older brother shot. Soldiers ripped him from his mother’s arms, and shot her when she tried to take her child back. Recent years have seen a flourishing of Jewish life and culture in Odesa, which before the latest invasion had a Jewish population of 35,000. A memorial event in 2018 attended by the German and Romanian ambassadors helped lay to rest the legacy of the massacres in 1941-42. “I wish every rabbi in the world would have the same freedom which I enjoy here. We have 11 buildings in this city, anything we need, the city provides,” Odesa’s chief rabbi, Avraham Wolff tells The Independent. “It is very painful what is going on for the Jewish community here. For the last few years, we have collected 35,000 people – 35,000 pieces of the puzzle – into one big picture. We built institutions, from kindergartens to nursing homes, from orphanages to a Jewish university. We made this picture, and then we framed it and we put it on the wall. But now it is falling down. Thirty-five thousand pieces of a puzzle scattered across Ukraine, Moldova, Germany and Israel. It is broken.” My final article of this year is also the last in a series I have written in recent months to honour the memories of those murdered at the ravine of Babi Yar on the outskirts of Kiev, Ukraine, 80 years ago. This time, I will end on a forward-looking note, discussing a new, thought-provoking piece of music theatre designed to move, challenge and inspire. In September 1941, the occupying Nazi forces and their Ukrainian collaborators murdered more than 33,000 Jews at Babi Yar over just two days, beginning on the eve of Yom Kippur. In the following two years of Nazi occupation, Babi Yar became the scene of over 100,000 deaths. This year a group of three Ukrainian musicians journeyed deep into their shared history, drawing on survivors' testimonies, traditional Yiddish and Ukrainian folk songs, poetry and storytelling to produce a new music theatre performance – Songs for Babyn Yar (to use the Ukrainian name for the killing site). The production weaves languages, harmonies and cultures to reveal the forgotten stories and silenced songs from one of the most devastating periods in Ukraine’s past and questions how we can move forward. Songs for Babyn Yar features haunting music from Svetlana Kundish, Yuriy Gurzhy and Mariana Sadovska, all originally from Ukraine but now based in Germany. They are ethnically Jewish and Russian Orthodox and between them perform in Ukrainian, Russian, English, German, Yiddish and Hebrew. Artistic director Josephine Burton, from the British cultural charity Dash Arts, has helped, in her words, “to tease out a narrative that will encompass this shared joy in each other, whilst not shrinking away from the darkness and the horrific tragedy at its heart”. In an interview with the London-based Jewish Chronicle in November, Kundish described the deeply personal link she feels to Babi Yar thanks to a 94-year-old survivor among the congregants of the synagogue in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony - where she serves as the first female cantor - and the close friendship they formed. When the Nazis occupied Soviet Ukraine in the summer of 1941, 13-year-old Rachil Blankman’s parents sent her away from Kiev to Siberia with a sick aunt, while they stayed behind to wait for Rachil’s missing brother to come home. The family that she left behind in Kiev were murdered at Babi Yar. The orphaned teenager eventually returned to Kiev and struggled through many years of hunger and of poverty, but eventually gained a university degree and became an engineer. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Rachil moved to Germany. “Her whole life story is a statement that despite everything, she found a way not only to survive, but also to live a happy life,” Kundish says. Rachil represents the “main voice” of Songs for Babyn Yar. “We have excerpts from the story of her life incorporated into the body of the show, so her voice comes in and out at certain moments, and the music is in a dialogue with her memories,” Kundish says. The willingness in Ukraine today to recognise the atrocities committed at Babi Yar, with major research projects and a new memorial centre underway (which I have written about here) contrasts sharply with the Soviet era, when Jewish memory and culture were all but erased. The Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was banned from reading his 1961 poem Babi Yar (which was later used by the composer Dmitry Shostakovich in his 13th symphony) in Ukraine until the 1980s. And Lithuanian soprano Nechama Lifshitz was barred from performing in Kiev after she sang Shike Driz’ Yiddish Lullaby to Babi Yar at a concert in the city in 1959. Kundish hopes that Songs for Babyn Yar will reach out to as wide an audience as possible and will be part of an ongoing conversation. “I want [people] to tell their children or grandchildren about it. I want them to keep the memory alive because this is a hard chapter of history and it should not be forgotten. And people who live in Ukraine, especially the young generation, they should know about it…I want it to be broadcast on Ukrainian television. I want people to accidentally push the button and end up on this channel and just listen. That’s what I want.” Songs for Babyn Yar debuted at JW3 in London on 21 November 2021 and will be performed at Theatre on Podol in Kiev on 7 December. A short extract is available on YouTube.  Until I was asked, a few weeks ago, to lay a wreath of white poppies at this year’s ceremony of remembrance in our local village, I hadn’t been aware of the symbolism of the white poppy. Unlike the red poppy, it commemorates all victims of war, civilian as well as military, in conflicts past and present, anywhere in the world. White poppies also symbolise a commitment to peace and challenge efforts to glamorise or celebrate war. Victims of war of course include not just those killed during conflict. They include all those who are wounded, bereaved or lose their homes and livelihoods, or live with the daily fear of stray bullets or explosions. They include refugees forced to flee their homes, those who undertake terrible journeys to try to reach a safe haven, who may find themselves held in camps in terrible conditions, locked up in detention centres abroad, or are made to feel unwelcome in the communities where they seek to make a new life. Today’s victims of war include girls in Afghanistan who have been forced to give up their education, all those suffering in war zones in Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, and many others. My children laid our homemade wreath of white poppies to honour the memories of two members of our own family in particular. The first is my grandmother’s cousin Moishe (pictured left). He was 16 in the summer of 1941 when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union where he lived. With his mother and younger sister, he fled his home town of Kiev just ahead of the advancing German army, heading east and finding refuge in the city of Kokand in Uzbekistan. On arrival, they found the city already overcrowded with evacuees and they lived in dreadful conditions, amid starvation levels of hunger and epidemics of typhus and other diseases. In 1943 Moishe was called up to a Soviet military academy in Turkmenistan. Then in 1944, he was transferred to the front – to Poland. He died on 16 October 1944, ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s final offensive to liberate Warsaw. He was 18 years old. But fleeing to Uzbekistan enabled Moishe’s mother and sister to escape almost certain death. Six million Jews like them were murdered by the Nazis during World War II. In much of Soviet Ukraine, the Nazis didn’t force Jews into ghettos and transport them to concentration camps, to the gas chambers, as they did in other parts of Europe. Instead, they rounded up the Jews and forced them to pits on the outskirts of towns and villages. In these pits, hundreds of thousands were shot by the Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators, in what is now referred to as the Holocaust by Bullets. But this wasn’t the only means of mass murder that the Nazis used in Ukraine. Our white poppy wreath also honours the memory of another of my grandmother’s cousins, Baya (pictured right). Baya and my Grandma grew up together. They were both orphans and were brought up by their grandparents in a village about 60 miles from Kiev. When my Grandma and most of her family managed to escape to the West in the 1920s – to Canada – Baya was the only member of the household who chose to stay behind. She was engaged to be married and was studying at university in Kiev. In 1941, when the Nazis invaded, Baya and her husband didn’t flee to the east. They stayed in Kiev, where they were among a group of Jews forced aboard a boat on the Dnieper, the river that cuts through the centre of the city. The boat was set alight. There were no survivors. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed