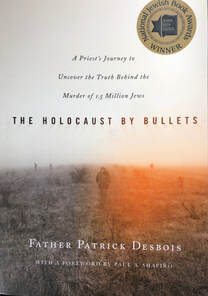

Ever more shocking documentary evidence continues to emerge of Russian atrocities in Bucha, 30 kilometres northwest of Kyiv. The horrors started to come to light in early April after the town’s liberation by Ukrainian forces. According to the latest reports by the BBC, around a thousand bodies have been recovered from Bucha, following nearly a month of occupation by Russian troops, including 31 children. Of these, more than 650 had been shot. The New York Times last week revealed video footage taken on 4 March, showing a group of nine Ukrainian captives being led at gunpoint by Russian troops. They walked in single file, their backs hunched, each holding onto the clothing of the man in front. At the front and back of the line of captives was a Russian soldier with a gun. They led the men behind an office building. Witnesses heard the gunshots, and drone footage shows dead bodies beside the building, with Russian soldiers standing over them. And the BBC reported the chilling signs of a massacre in a children’s holiday camp on the edge of woodland in Bucha. Promenystyi, or Camp Radiant, is decorated with mosaics showing happy children against a background of rays of bright sunshine. A basement at the camp was transformed into a torture chamber, where five men were found crouching on their knees, heads down and hands bound behind their backs. They had been tortured and shot. More than a dozen bullet holes were visible in the walls, surrounded by patches of dried blood. This wasn’t the first time that the basement of a holiday camp had been used as a torture chamber. In nearby Zabuchchya, Ukrainian forces in early April discovered eighteen burnt and mutilated bodies of men, women and children, some with ears cut off, others with teeth pulled out, and many with their hands tied behind their backs. Girls as young as fourteen had been raped by Russian soldiers. The Russian authorities have repeatedly denied responsibility for the massacre of civilians in Bucha and elsewhere. They have claimed that the reports were staged or faked, as a provocation by Ukraine. That these horrors are taking place in Europe, in 2022, is hard to fathom. These very same towns and villages were the scene of some of the most terrible atrocities of World War II, events that brought the international community together to declare “Never Again” - an avowal that has been breached all too many times. I have just finished reading a book of witness accounts of the mass killings of Jews in Ukraine in 1941-44. Father Patrick Desbois, a French priest, spent several years in the early 2000s travelling around the small towns and villages of rural Ukraine seeking out and interviewing hundreds of elderly people who, as children sixty years earlier, had seen, heard or even participated in, the Holocaust by Bullets, in which 1.5 million people were executed. These were the earliest mass victims of the Holocaust. They were not transported in cattle trucks to concentration camps, but taken on foot, on peasant carts, or in German military trucks, to sites often in or near woodland, just outside the towns and villages where they lived. Here they were shot in large pits or ditches, that they were often forced to dig themselves. They were shot at close range, sometimes face-to-face, but more often in the back. They were murdered in the presence of local residents. Their non-Jewish neighbours, even friends, or school classmates. Together with an international group of researchers, interpreters, photographers and even a ballistics expert, Father Desbois used forensic evidence, eyewitness accounts and archival material to uncover the burial sites and the brutal stories behind them. His book provides a definitive and harrowing account of a rarely explored chapter in the story of the Holocaust. I have read and written so much about the Holocaust and the earlier pogroms against the Jews in Ukraine, that I am not easily shocked by accounts of extreme violence. But both the reports of atrocities in Bucha, and the witness interviews conducted by Father Desbois, are agonising to read and have shaken me to the core. That such horrific crimes as those perpetrated in Ukraine again and again in 1941-44 could be repeated now, in 2022, is utterly beyond belief.

1 Comment

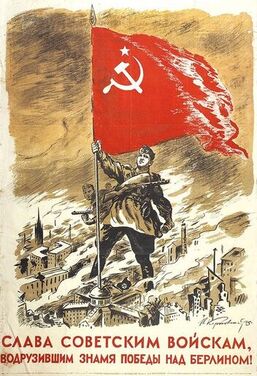

Victory Day, on 9 May, is the most solemn and serious of national celebrations in Russia. On this date thirty years ago, I was in the southern Russian city of Voronezh. It was a beautiful, sunny day, the warmest of the year so far after a long, bleak winter. The main street was closed to traffic and it seemed the whole population of the city was outdoors. But the glorious holiday weather didn’t prompt people to shed layers of clothing and relax with picnics and drinks in the city’s parks as they might have elsewhere. Instead, families walked, silent and sombre, towards the war memorial to lay flowers, three or four generations together. The older men wore rows of medals with multi-coloured ribbons attached to their jackets. Many were dressed in military uniform. The women were togged up in their Sunday best. Children were primped and preened with oversize bows for the girls and buckles and braces for the boys. Although the holiday celebrated the victory of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is known – there was no sense of jubilation. The Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the victory and the war took a terrible toll. An estimated 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Every family lost a son, a brother, a father, an uncle or a cousin. The pomp and ceremony of today’s Victory Day parade in Moscow add some glitz and glamour that didn’t exist in the immediate post-Soviet era. And of course, the war in Ukraine adds poignance to the occasion. It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin in his Victory Day speech linked the current conflict with the triumph over Nazi Germany. Time and again, he has drawn parallels between the two wars, starting with his bizarre notion of the need for Russia to rid Ukraine of Nazis. Given the Jewish origins of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, the Nazi tag has struggled to stick. But Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comparison of Zelensky with Adolf Hitler, in an attempt to legitimise Russia’s goal of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, took the analogy up a notch. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst anti-Semites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood – statements that typify the distortion of history that underpin Russia’s war with Ukraine. The question of Hitler’s Jewish identity is nothing new – and remains unproven. The issue centres on Hitler’s father, born in Graz, Austria, in 1837 to an unmarried mother. Speculation over who the child’s father was has continued for decades, fuelled by the fact that following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the records of his grandmother’s community to be destroyed. A memoir by Hans Frank, head of Poland’s Nazi government during the war, claimed that the son of Hitler’s half-brother tried to blackmail the Nazi dictator, threatening to expose his Jewish roots. Following worldwide outrage over Lavrov’s comments, and in particular heated condemnation from Israel, the Russian president was forced to issue a rare apology to his Israeli counterpart, Naftali Bennett, rather than risk alienating a country that has been more supportive than most. Israel has been an ally of Russia since the end of the Soviet Union – based in part on both countries’ military interests in Syria and the substantial Russian-Jewish population in Israel – and has faced criticism for failing to join Western sanctions. Israeli foreign minister Yair Lapid said Lavrov’s comments “crossed a line” and condemned his claims as inexcusable and historically erroneous, while Dani Dayan, head of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem, denounced them as “absurd, delusional, dangerous and deserving of condemnation”. Russia’s foreign ministry hit back, accusing the Israeli government of supporting a neo-Nazi regime in Kyiv. Only time will tell if the war of words leads to firmer Israeli support for Ukraine. Russian TV host Vladimir Solovyov last week pushed the Nazi narrative further, clarifying a new definition of Nazism to explain the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. “Nazism doesn’t necessarily mean anti-Semitism, as the Americans keep concocting. It can be anti-Slavic, anti-Russian,” he said. To keep its phoney narrative alive, Russia will keep churning out the rhetoric on Nazism in the hope that if it repeats it often enough and loudly enough, more people will believe it. But the longer Putin’s Russia continues murdering Ukrainian citizens and bombarding Ukrainian cities, the more it resembles Hitler’s Nazi regime. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed