The election of Volodymyr Zelensky as president of Ukraine has baffled most casual observers. That a comedian best known for his TV role as a schoolteacher who accidentally becomes president has been elected as the actual president is a bizarre example of life imitating art. And that a Jew, in a land with a long and brutal history of anti-Semitism, should win a landslide victory is puzzling in itself. It also makes Ukraine the only country apart from Israel to have both a Jewish president and prime minister. As the Russian-Israeli columnist Avigdor Eskin put it in a Regnum news agency article, “Imagine, a pure-blooded Jew with the appearance of a Sholom Aleichem protagonist wins by a landslide in a country where the glorification of Nazi criminals is enacted into law”. Zelensky’s election may be an example of how celebrity and populism have displaced serious political debate in the era of Donald Trump. Indeed, citizens of Ukraine’s capital Kiev already elected the celebrity ex-boxer Vitali Klitschko as mayor back in 2014. That a man with no experience of politics should become president is perhaps less surprising in Ukraine than elsewhere. Politicians have given themselves a bad name here. Since its separation from the Soviet Union in 1991 the country has been ruled by a series of corrupt leaders, mostly super-rich oligarchs who made their fortunes by dubious means in the anarchic aftermath of independence. Indeed, many of those protestors who braved the cold and the bullets during the Euromaidan revolution of 2013-14 were motivated not only by then-president Viktor Yanukovych’s volte-face on European integration, but also by the engrained corruption in Ukrainian political life which Yanukovych’s excessive wealth – and poor taste – exemplified. Incumbent president Petro Poroshenko, an oligarch who made his fortune in confectionary giving him the moniker the Chocolate King, has done little to address the political graft in spite of his promises. But it is well known that Zelensky is promoted and supported by one of Ukraine’s most controversial oligarchs, Igor Kolomoisky. Kolomoisky lives in self-imposed exile in Israel owing to an investigation into his financial affairs and is a political rival to Poroshenko. He owns the TV channel on which Zelensky’s TV comedy airs and the two men apparently have business partners in common, although both insist their relationship is purely professional. Zelensky’s election manifesto was almost entirely blank. He avoided interviews and campaign rallies in favour of comedy shows, and promoted himself by means of social media and YouTube. It is unsurprising, therefore, that Zelensky has proven particularly popular among the young. But he also garners support among native Russian speakers in this divided society, partly because of his lack of involvement in the 2014 revolution. Russian president Vladimir Putin will no doubt be delighted to see the back of Poroshenko, a pro-Westerner who has had an antagonistic relationship with Russia. But the few clues that Zelensky has offered indicate that his foreign policy will follow a similar trajectory. Ukraine is expected to continue to drift towards the EU and not to accept the annexation of Crimea and the occupation of Donbas, although critics have accused Zelensky of too soft a stance towards Russian aggression. The President-elect has talked of a referendum on whether to join the EU and NATO when the time is right. Zelensky was the subject of a Russian investigation in August 2014 after he performed for Ukrainian troops on the frontline in eastern Ukraine and donated 1 million hryvnia ($37,000) to fighting the Russian-backed separatists. More recently, he has stated that his “number one task” will be to try to bring home 24 Ukrainians held in Russia since their capture in a naval incident near Crimea in February. He has also endorsed the deployment of UN peacekeepers in the Donbas, as well as ruling out the granting of special status to the breakaway regions of Donetsk and Luhansk. Ukraine is a country with serious problems. In addition to its tricky relationship with its powerful neighbour – which manifests itself in the well-known divisions between ethnic Ukrainians and Russians, the ongoing conflict in the Donbas and Russia’s annexation of Crimea – Ukraine’s economic performance is pitiful and its politics and society rife with corruption. It needs a serious politician to deal with such essential issues. Whether an actor and comedian will be able to play that role remains to be seen.

0 Comments

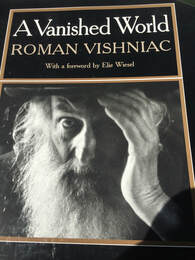

I recently received as a gift a stunning book of photographs by the Jewish photographer Roman Vishniac. The photos were taken in the shtetls of eastern Europe in the 1930s, just before those communities were wiped out forever. A Vanished World was published in New York in 1983. It is difficult to get your hands on a copy of it now, but the photographs it contains serve as an important historical document. Vishniac was born in Russia, but was living in Germany in the 1930s. He took the photographs between 1934 and 1939, when the Nazis had already taken power, and when anyone with a camera was at risk of being branded a spy – and in communities where observant Jews did not want to be photographed for religious reasons. But he had the foresight to see what few others could possibly imagine, that the Nazis would systematically wipe out the shtetls and Jewish communities that had existed and maintained the same way of life for hundreds of years. He made it his mission to not let their inhabitants, along with their occupations and preoccupations, be forgotten. “I felt that the world was about to be cast into the mad shadow of Nazism and that the outcome would be the annihilation of a people who had no spokesman to record their plight. I knew it was my task to make certain that this vanished world did not totally disappear”, he says in his commentary on the photos. Vishniac used a hidden camera, at a time when photography was in its infancy and equipment was bulky and unsophisticated. He put himself at great risk, and was thrown into prison for a time, but still he persisted in his mission, constantly running the risk of being stopped by informers or arrested by the Gestapo. He managed to take around 16,000 photographs, although all but 2,000 were confiscated and, presumably, destroyed. He chose to include around 200 in this book, the images that he considered the most representative. He travelled from country to country, taking in Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Ukraine and Lithuania, from province to province, village to village. He captured images of slums and markets, street scenes and school houses, from the wrinkled faces of old men and careworn mothers to pale religious scholars and hungry, wild-eyed children. The images are far from anonymous. Vishniac got to know the people he photographed, he often availed of their hospitality and spent time working and living among them. He slept in a basement that was home to 26 families, sharing a bed with three other men. “I could barely breathe, Little children cried; I learned about the heroic endurance of my brethren,” he wrote. He spent a month working as a porter in Warsaw, pulling heavy loads in a handcart, in one of the very few occupations still open to Jews during the Jewish boycott in the late 1930s, which forced tens of thousands of Jewish employees out of their workplaces. It was cheaper to have a Jew pulling a cart than a horse, for the horse had to be fed before it would work, while Jews were forced to carry the goods first and eat later, only once they had been paid. As one reviewer, the American photographer and museum curator Edward Steichen, wrote, “Vishniac took with him on this self-imposed assignment – besides this or that kind of camera or film – a rare depth of understanding and a native son’s warmth and love for his people. The resulting photographs are among photography’s finest documents of a time and place”. Vishniac emigrated to New York in 1940 and became an acclaimed photographer and professor of biology and the humanities. His only son Wolf died in Antarctica while leading a scientific expedition, and his grandson Obie died at the age of just 10. The book is dedicated to them, as well as to Vishniac’s grandfather. He writes: “Through my personal grief, I see in my mind’s eye the faces of six million of my people, innocents who were brutally murdered by order of a warped human being. The entire world, even the Jews living in the safety of other nations, including the United States, stood by and did nothing to stop the slaughter. The memory of those swept away must serve to protect future generations from genocide. It is a vanished but not vanquished world, captured here in images made with hidden cameras, that I dedicate to my grandfather, my son and my grandson." |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed