This week marks the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Seeing satellite images of a long line of Russian tanks heading towards Kyiv on that awful morning, few believed that the war would last more than a handful of days; weeks at most. I wrote at the time that Russian president Vladimir Putin had a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him, as he stepped up his attempts to recreate Stalin’s Soviet empire by taking control of Ukraine. Now that whiff has become more of a stench. The death of Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most prominent critic, on 16 February makes the parallels between the two dictators starker than ever. Like Stalin, Putin views the outside world as a hostile and threatening place and brooks no dissent. Stalin subjected his opponents to show trials, found them guilty on trumped-up charges and had them shot. Today, anyone who publicly opposes Putin’s regime, who attempts to tell the truth, expose the corruption, is a grave threat. Putin’s methods of silencing opponents are more varied – imprisonment, poison, shooting, defenestration, a plane falling from the sky. Again like Stalin, Putin heads a cruel and corrupt administration, but has built a personality cult around himself to appear as a paternalistic leader who has the best interests of his citizens at heart. Both regimes have been guilty of hiding or falsifying data and masking the truth with a state-sanctioned view of world events and a thick veneer of propaganda. At the time of writing, the cause of Navalny’s death is unclear. A video taken the previous day showed him looking surprisingly well given the inhumane conditions in which he was incarcerated. His family and legal team have repeatedly been refused access to a mortuary where his body is believed to lie. Just days before Navalny’s death, another Russian politician, Boris Nadezhdin, was barred on technical grounds from standing against Putin in next month’s presidential election. Nadezhdin has been careful to play by the Kremlin’s rules, to avoid calling out or criticising Putin, but he is a vocal opponent of the war in Ukraine. Russia-watchers had considered he might be allowed to remain on the ballot to give the appearance of competition, and to provide a narrative for Putin to rally against. But Nadezhdin proved too popular. A hundred thousand Russians flocked to sign supporter lists to enable him to stand against Putin, so the electoral commission ruled that thousands of the signatures he had gathered were fraudulent. Nadezhdin continues to appeal the ruling, but he must now be looking over his shoulder in case FSB officers are sent to arrest him, just as those who opposed Stalin’s regime lived in fear of a knock at the door in the middle of the night. Another parallel between Putin’s Russia and Stalin’s Soviet Union can be found in the Russian-occupied cities of eastern Ukraine, where the Kremlin is carrying out ethnic cleansing just as it did in the 1940s. In Mariupol, Zaporizhzhia and other cities located in the regions where the Kremlin held rigged referendum votes on becoming part of Russia, the occupying authorities are doing all they can to wipe out Ukrainian identity. Mariupol, before the war a pleasant, leafy coastal city on the Sea of Azov, was besieged and almost razed to the ground in the spring of 2022. Now smart, Russian-built apartment blocks line newly reconstructed avenues planted with lawns and neat rows of trees. In these apartments live recently arrived Russians, shipped in from the Motherland with the promise of better housing, good jobs, higher wages. Many of the previous inhabitants fled the bombardment back in 2022, or were killed or taken prisoner during the siege. What’s more, around 5 million Ukrainians from the occupied territories are estimated to have been deported to Russia in the last two years, including 700,000 children. Those who stayed and survived, or returned, were forced to acquiesce with the occupying authorities, to become Russian. Access to social services, including pensions and maternity payments, is only available to those with Russian passports. This in turn means babies are born to Russian rather than Ukrainian nationals, and inherit Russian citizenship. They will go to schools where they are taught in Russian, be subject to Russian cultural influences and learn a Russian history curriculum filled with hateful rhetoric about Ukrainian Nazis. Refusal to apply for a passport of the occupying power leaves defiant Ukrainians living a shadowy undercover existence, while any show of insubordination is likely to land them in a Russian prison. Crimea has experienced the same manipulations of population and bureaucracy for the last decade, since the Russian annexation in March 2014. Ukrainians were forced out or coerced into giving up their citizenship, native Russians were encouraged to settle, and only those holding Russian passports can access schools, hospitals and social services. Most Russians, and many outside Russia, have long believed that Crimea was not really Ukrainian, that it was something of a Russian enclave inside Ukraine. After all, it had only become part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954, transferred by then premier Nikita Khrushchev from the Russian Federation (for reasons I discussed in a previous article). Crimea’s population at that time was roughly 75% Russian and it was home to the Soviet (now Russian) Black Sea Fleet. But that only tells a small part of Crimea’s story. The peninsula, strategically located at the centre of the Black Sea, was wrested from the Ottoman Empire by Russia in 1783 under Catherine the Great. Its population for centuries had been predominantly Crimean Tatar – a Turkic-speaking, Sunni Muslim ethnic group. In 1944, Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars en masse to Siberia, the Urals and Central Asia and expelled Crimea’s smaller populations Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians. The peninsula was repopulated with ethnic Russians. Since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, many Crimean Tatars had returned to their homeland, along with other ethnic groups, who were granted citizenship rights by the Ukrainian government.

1 Comment

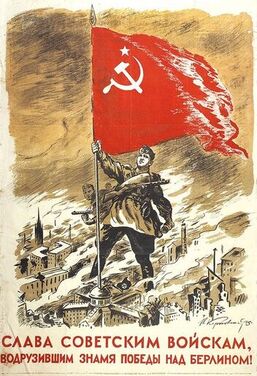

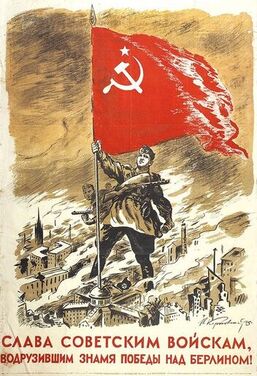

Eighty years ago, the biggest Jewish revolt against Nazi aggression was under way. The Warsaw ghetto uprising, which lasted from 19 April-16 May 1943, was an attempt to prevent the deportation of the remaining population of the ghetto to the gas chambers. The previous summer, more than a quarter of a million Jews had been transported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Foreseeing their own fate, the remaining residents developed resistance movements, smuggled weapons into the ghetto and prepared to fight. They knew that victory was impossible; they fought instead for the honour of the Jewish people, and to prevent the Germans from choosing the time and place of their deaths. On 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover, Germans entering the ghetto to begin the deportation were met by gunfire, grenades and Molotov cocktails. Pitched battles raged for days, until the Germans resorted to burning down the ghetto, block by block. Thousands of Jews took refuge in sewers and bunkers, which the Nazis then destroyed. The uprising came to an end on 16 May 1943. Around 13,000 Jews had died, and a further 55,000 were captured and taken to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek. The presidents of Germany, Poland and Israel gathered on 19 April at a memorial on the site of the former ghetto to mark the 80th anniversary of the uprising. “I stand before you today and ask for forgiveness,” German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier said. “The appalling crimes that Germans committed here fill me with deep shame… You in Poland, you in Israel, you know from your history that freedom and independence must be fought for and defended, but we Germans have also learned the lessons of our history. ‘Never again’ means that there must be no criminal war of aggression like Russia’s against Ukraine in Europe.” A 96-year-old Polish Holocaust survivor, Marian Turski, warned against apathy in the face of rising hatred and violence. “Can I be indifferent, can I remain silent, when today the Russian army is attacking our neighbour and seizing its land?” he questioned. The anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising comes as Russia is preparing to commemorate its own wartime anniversary – that of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. The Kremlin continues to draw parallels between the Second World War and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that Russia is fighting Nazis and battling for its survival against an aggressive force from the West that his hellbent on its annihilation. Russia’s motivation for its war in Ukraine is to ensure that “there is no place in the world for butchers, murderers and Nazis,” Putin said last year. “Victory will be ours, like in 1945.” But Victory Day, celebrated in lavish style on 9 May every year in Russia, will entail less pomp and ceremony than usual. Several cities are scaling back their celebrations for security reasons, fearing attacks by pro-Ukrainian forces following a spate of explosions and fires in recent days involving Russian energy, logistics and military facilities. The reduced scale of events also signals a degree of nervousness that the parades could become an outlet for disaffection with the war in Ukraine. Most notably, Immortal Regiment processions, which take place in all major towns and cities across Russia, have been cancelled this year. During the parades, hundreds of thousands of people march carrying photographs of relatives who fought or died during World War II. Putin himself attended an Immortal Regiment march in Moscow last year, holding a portrait of his father. The procession is a key event in the glorification of Russian sacrifice in the defeat of Nazi Germany – a cornerstone of Russia’s nationalist resurgence during Putin’s two decades in power. Ostensibly called off because of fears of a terrorist attack, Immortal Regiment processions risk highlighting the human cost of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The Kremlin fears that thousands of Russians would march with photographs of family members killed in the current war, bringing into sharp focus Russia’s mounting losses, and potentially risking the morphing of processions into protest events. The Russian authorities remain tight-lipped about the scale of the country’s losses in Ukraine. The most recent update came back in September, when the military reported that nearly 6,000 Russian soldiers had lost their lives. The US estimates Russian casualties in Ukraine to amount to over 200,000 dead or wounded. During last year’s Victory Day celebrations, 125 people were detained for protesting about the war, many of them at Immortal Regiment parades.  Moscow’s former chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, has urged Russian Jews to leave the country while they still can, warning that they may become scapegoats for difficulties caused by the war in Ukraine. Goldschmidt – who resigned in July because of his opposition to the war and lives in exile – pointed to numerous historical precedents for today’s rising antisemitism. “When we look back over Russian history, whenever the political system was in danger you saw the government trying to redirect the anger and discontent of the masses towards the Jewish community,” he told The Guardian. “We saw this in tsarist times and at the end of Stalin’s regime.” Antisemitism was rife under the tsars, and waves of pogroms in 1881-1906 were condoned by the tsars, if not actually encouraged by them. Often the police were ordered not to intervene, and sometimes even joined in the antisemitic attacks and looting. Up to two million Jews left Russia as a result of the pogroms. Attacks on Jewish communities peaked in 1919 during the Russian civil war, in Ukraine in particular, when numerous different factions fought for control of the land. All of them committing acts of violence against Jews who were blamed both for food scarcity and rising prices, and for supporting the Bolsheviks. Discrimination and antisemitism prompted many Jews to back the Bolshevik regime, which banned religion of any kind and proclaimed all citizens as equal – although the reality was a far cry from the rhetoric. Official government-led antisemitism remerged in 1953 under Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in the form of the Doctors Plot – an alleged conspiracy by a group of mostly Jewish doctors to murder leading Communist Party officials. The plot was thought to be a precursor to another major purge of the party, and was halted only by Stalin’s death. Once again, as a backdrop to today’s ugly war, history is repeating itself. “We’re seeing rising antisemitism while Russia is going back to a new kind of Soviet Union, and step by step the iron curtain is coming down again. This is why I believe the best option for Russian Jews is to leave,” Goldschmidt said. Jews are increasingly being blamed for Russia’s difficulties in the war – Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky is Jewish, of course. The Russian government and state-controlled media, as well as many on the far right, routinely repeat antisemitic tropes and conspiracy theories. Foreign secretary Sergei Lavrov in May trotted out the unfounded claim that Hitler was part-Jewish, in a crude attempt to portray Zelensky as a Nazi. Goldschmidt served as Moscow’s chief rabbi for over 30 years until he resigned in July, prompted by fears that the city’s Jewish community would be endangered if he stayed, after he refused to voice support to the war and gave assistance to Ukrainian refugees. He had already left Russia in March, two weeks after the invasion of Ukraine began. “Pressure was put on community leaders to support the war, and I refused to do so. I resigned because to continue as chief rabbi of Moscow would be a problem for the community because of the repressive measures taken against dissidents,” he said. Goldschmidt first urged Russian Jews to flee the country in October after the assistant secretary of Russia’s Security Council, Aleksey Pavlov, proclaimed the Jewish orthodox Chabad movement to be a supremacist cult. Chabad is the largest Jewish sect in the former Soviet Union. “Now we are under pressure, wondering if what was published in the newspaper — this interview with a top security official — represents the start of an official wave of antisemitism. I think that would be the end of a Jewish presence in Russia. Official antisemitism would drive every Russian Jew out of the country,” Baruch Gorin, a spokesperson for the Russian Jewish community, said at the time. Since July, Russia has been engaged in a legal battle with Israel over its attempts to close down the Russian branch of the Jewish Agency, an Israeli quasi-governmental organisation that promotes Jewish immigration to Israel and organises Jewish cultural and educational activities in Russia. Moscow’s efforts call to mind earlier crackdowns on the organisation and on Jewish communal life during Soviet times. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Goldschmidt estimates that between a quarter and a third of Russia's Jews have left the country or are planning to do so. More than 43,000 Russians and 15,000 Ukrainians emigrated to Israel last year. In all, some 200,000 Russians have left the country since the war began, many of them as a result of Putin’s mobilisation drive in September. Jews comprise a disproportionate number of Russia’s middle class and the exodus marks a considerable brain drain for Russia, with a large contingent of business and cultural leaders, intellectuals and creatives fleeing the country.  Ukraine on 26 November marked the 90th anniversary of the Holodomor – the famine of 1932-33 in which millions of Ukrainians died. Since 2006, the country has recognised the Holodomor as a deliberate act of genocide against the Ukrainian people, perpetrated by the Soviet authorities under Joseph Stalin. The anniversary falls as Russia is once again using food as a weapon of war, both against the Ukrainian people and the rest of the world, and with Ukrainians again facing what may be perceived as genocide at the hands of a Russian regime that denies Ukraine’s right to statehood. “Ninety years after the Holodomor genocide committed on the territory of Ukraine, Russia is committing a new genocide – war. The eternal enemy is again trying to “denationalise” and suppress us so as not to let us out of its influence and prevent the strengthening of Ukrainian statehood. The methods of the latest Putin regime differ little from Stalin’s: murder, terror with hunger and cold, intimidation, and deportation,” Kyiv’s Holodomor museum said on 16 November. The term Holodomor derives from the Ukrainian words for hunger (holod) and extermination (mor). Between 3.5 million and 7 million people are estimated to have died in Ukraine’s grain producing regions during the Holodomor. The famine peaked in the summer of 1933, when the daily death toll from starvation is estimated at around 28,000. During this period, the Soviet Union exported 4.3 million tonnes of grain from Ukraine to earn hard currency to pay for its industrialisation drive. The famine came about as a result of Stalin’s policy to collectivise agriculture, forcing those who lived and worked on the land to give up their farm holdings and personal possessions to join the new collective farms. Collectivisation faced mass opposition in many parts of the Soviet Union, including Ukraine, and led to lower production and food shortages. In November 1932, Stalin dispatched agents to seize grain and livestock from newly collectivised Ukrainian farms, including the seed grain needed to plant crops the following year. While other grain-producing regions of the Soviet Union also suffered mass hunger as a result of collectivisation, the policies enacted in Ukraine were far more brutal than elsewhere, with whole villages and towns blacklisted and prevented from receiving food, as Stalin sought to stifle rebellions and armed uprisings by Ukrainian resistance movements. Yale University historian Timothy Snyder has referred to the mass starvation that followed as “clearly premeditated mass murder”. The harsh reprisals against Ukrainians included a campaign of repression and persecution against Ukrainian culture, religious leaders and anyone accused of Ukrainian nationalism. The Soviet authorities denied the existence of famine, prevented travel to the regions affected and suppressed reports of it, refusing offers of assistance from the Red Cross and other humanitarian organisations once news of the tragedy leaked out. The parallels between Stalin’s repression of Ukraine in the early 1930s and Russian president Vladimir Putin’s actions 90 years later are stark. Russia’s targeting of grain storage facilities and its blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea exports have sparked accusations that Moscow is using food as a weapon of war. And repeated waves of attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure are cutting off electricity and water supplies with the aim of breaking the resolve of the Ukrainian people, just as the withdrawal of food supplies did during the Holodomor. "On the 90th anniversary of the 1932-1933 Holodomor in Ukraine, Russia's genocidal war of aggression pursues the same goal as during the 1932-1933 genocide: the elimination of the Ukrainian nation and its statehood," Ukraine's foreign ministry said in a statement. And Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky said in a video posted on social media, “Once they wanted to destroy us with hunger, now – with darkness and cold…. We cannot be broken.” Several European leaders – including from Belgium, Lithuania and Poland – travelled to Ukraine for the anniversary to pledge their support for the country. Other nations, including Germany and Ireland – which suffered its own devastating famine in the 19th century – are joining Ukraine in recognising the Holodomor as a genocide on the Ukrainian people. And Michael Carpenter, the US ambassador to the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, addressed its permanent council in Vienna with a damning statement: “The men, women, and children who lost their lives during this famine were the victims of the brutal policies and deliberate acts of the regime of Joseph Stalin. This month, as we commemorate those whose lives were taken, let us also recommit ourselves to the constant work of preventing such tragedies in the future and lifting up those suffering under the yoke of tyranny today. “It is especially important this year to remember that the word “Holodomor” means “death by hunger.” Putin’s regime is demonstrating its brutality in Ukraine by conducting attacks across Ukraine’s agriculture sector and by seizing Ukraine’s grain, effectively using food as a weapon of war.” Ukrainians typically mark the anniversary, which falls on the fourth Saturday of November, by placing candles in their windows. Today they need those candles to light their homes.  Victory Day, on 9 May, is the most solemn and serious of national celebrations in Russia. On this date thirty years ago, I was in the southern Russian city of Voronezh. It was a beautiful, sunny day, the warmest of the year so far after a long, bleak winter. The main street was closed to traffic and it seemed the whole population of the city was outdoors. But the glorious holiday weather didn’t prompt people to shed layers of clothing and relax with picnics and drinks in the city’s parks as they might have elsewhere. Instead, families walked, silent and sombre, towards the war memorial to lay flowers, three or four generations together. The older men wore rows of medals with multi-coloured ribbons attached to their jackets. Many were dressed in military uniform. The women were togged up in their Sunday best. Children were primped and preened with oversize bows for the girls and buckles and braces for the boys. Although the holiday celebrated the victory of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is known – there was no sense of jubilation. The Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the victory and the war took a terrible toll. An estimated 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Every family lost a son, a brother, a father, an uncle or a cousin. The pomp and ceremony of today’s Victory Day parade in Moscow add some glitz and glamour that didn’t exist in the immediate post-Soviet era. And of course, the war in Ukraine adds poignance to the occasion. It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin in his Victory Day speech linked the current conflict with the triumph over Nazi Germany. Time and again, he has drawn parallels between the two wars, starting with his bizarre notion of the need for Russia to rid Ukraine of Nazis. Given the Jewish origins of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, the Nazi tag has struggled to stick. But Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comparison of Zelensky with Adolf Hitler, in an attempt to legitimise Russia’s goal of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, took the analogy up a notch. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst anti-Semites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood – statements that typify the distortion of history that underpin Russia’s war with Ukraine. The question of Hitler’s Jewish identity is nothing new – and remains unproven. The issue centres on Hitler’s father, born in Graz, Austria, in 1837 to an unmarried mother. Speculation over who the child’s father was has continued for decades, fuelled by the fact that following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the records of his grandmother’s community to be destroyed. A memoir by Hans Frank, head of Poland’s Nazi government during the war, claimed that the son of Hitler’s half-brother tried to blackmail the Nazi dictator, threatening to expose his Jewish roots. Following worldwide outrage over Lavrov’s comments, and in particular heated condemnation from Israel, the Russian president was forced to issue a rare apology to his Israeli counterpart, Naftali Bennett, rather than risk alienating a country that has been more supportive than most. Israel has been an ally of Russia since the end of the Soviet Union – based in part on both countries’ military interests in Syria and the substantial Russian-Jewish population in Israel – and has faced criticism for failing to join Western sanctions. Israeli foreign minister Yair Lapid said Lavrov’s comments “crossed a line” and condemned his claims as inexcusable and historically erroneous, while Dani Dayan, head of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem, denounced them as “absurd, delusional, dangerous and deserving of condemnation”. Russia’s foreign ministry hit back, accusing the Israeli government of supporting a neo-Nazi regime in Kyiv. Only time will tell if the war of words leads to firmer Israeli support for Ukraine. Russian TV host Vladimir Solovyov last week pushed the Nazi narrative further, clarifying a new definition of Nazism to explain the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. “Nazism doesn’t necessarily mean anti-Semitism, as the Americans keep concocting. It can be anti-Slavic, anti-Russian,” he said. To keep its phoney narrative alive, Russia will keep churning out the rhetoric on Nazism in the hope that if it repeats it often enough and loudly enough, more people will believe it. But the longer Putin’s Russia continues murdering Ukrainian citizens and bombarding Ukrainian cities, the more it resembles Hitler’s Nazi regime.  This year’s Holocaust Remembrance Day falls today, 28 April. Yom HaShoah is a national holiday in Israel held on or just before the 27the day of Nisan in the Hebrew calendar. The date marks the anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, when Jewish resistance fighters attempted to halt the Nazis’ final effort to transport the city’s remaining Jews to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek, the largest single revolt by Jews during World War II. Further east, in Soviet Ukraine, the Holocaust took a different form. Rather than ghettos and concentration camps, the Nazis used bullets and executions in mass graves on the outskirts of towns and villages. Vanda Semyonovna Obiedkova lived in Zhdanov, a city in eastern Ukraine named after the Soviet politician Andrei Zhdanov. Ten-year-old Vanda hid in a basement when the SS came to take away her mother after the Germans invaded in October 1941. On 20 October 1941, the Nazis executed up to 16,000 Jews in pits dug on the outskirts of the city, including Vanda’s mother and all her mother’s family. The SS later found Vanda and detained her, but family friends were able to convince them that the little girl was Greek, rather than Jewish. Her father, a non-Jew, managed to get her admitted to a hospital, where she remained until the liberation of Zhdanov in 1943. Today Zhdanov is known as Mariupol. In a haunting echo of her escape from the Nazis more than 80 years ago, 91-year-old Vanda was forced once again to hide in a basement when the Russian army began bombing the city in early March. She died there on 4 April. “There was no water, no electricity, no heat — and it was unbearably cold,” her daughter Larissa told Dovid Margolin in an interview with Chabad.org. Although Larissa tried to care for her mother, “there was nothing we could do for her. We were living like animals,” she said. It was too dangerous even to go out to find water as two snipers had set up positions near the closest water supply. “Every time a bomb fell, the entire building shook,” Larissa said. “My mother kept saying she didn’t remember anything like this during World War II… Mama didn’t deserve such a death”. In her final two weeks, Vanda was no longer able to stand. She lay freezing and pleading for water, asking, “Why is this happening?”. Larissa and her husband dodged the shelling to bury her in a public park near the Sea of Azov. “Mama loved Mariupol; she never wanted to leave,” she said. Vanda gave an interview to the USC Shoah Foundation in 1998, documenting her life story and Holocaust experience. “We had a VHS tape of her interview at home,” Larissa said, “but that’s all burned, together with our home.” In 2014, when fighting broke out in Mariupol as Russian separatists threatened to take the city, Larissa and her family – along with many of the city’s Jews – were evacuated to Zhitomir, in the west of the country, with the help of Rabbi Mendel Cohen, the city’s only rabbi and director of Chabad-Lubavitch in Mariupol. The family returned after Ukrainian troops secured the city, but Larissa said there’s no going back this time. She and her family were evacuated by Rabbi Cohen for a second time after her mother’s death. “I’m so sorry for the people of Mariupol. There’s no city, no work, no home — nothing. What is there to return to? For what? It’s all gone. Our parents wanted us to live better than they did, but here we are repeating their lives again,” she said. Vanda is the second Holocaust survivor known to have died in the war in Ukraine, after 96-year-old Boris Romanchenko, who was killed during a Russian attack on Kharkiv. He survived the Nazi concentration camps of Buchenwald and Bergen Belsen. The full interview is available here Photo of Vanda and her parents published with permission of Chabad.org  As 2022 begins, this might not feel like the happiest of new years, with Omicron cases surging and another wave of Covid restrictions in many countries. But spare a thought for the inhabitants of Leningrad (now St Petersburg) who attempted to celebrate the new year 80 years ago in their besieged city back in 1941-42. For those suffering mass starvation, cakes made from potato peel, a thin soup, aspic derived from wood glue, a slice of bread and a spoonful of jelly amounted to a genuine feast. The Nazis’ Siege of Leningrad – the Soviet Union's second largest city – lasted from September 1941 to January 1944, with enemy forces encircling the city and attempting to bomb and starve it into submission. Hundreds of thousands of residents died of hunger and cold during the first winter of the blockade. Lake Ladoga, the so-called Road of Life, provided the city's only link with the outside world, enabling precarious deliveries of urgent supplies by boat in summer and by truck over its frozen surface in winter, under constant enemy fire. The driver's door was removed from all the trucks making the crossing to enable the driver to leap to safety if the truck broke through the ice and sank. The ice road was busy day and night, but this was not enough to provide sufficient food supplies for such a large city. Bread rations were constantly being reduced and soon Leningrad faced mass hunger in spite of the makeshift canteens set up across the city. People fainted at their workplaces from exhaustion and some resorted to cannibalism or murder to attain extra food ration cards. By the beginning of the winter, there was no electricity, no running water and no heating; and the hundreds of corpses lying on the streets no longer shocked anyone. Residents rarely ventured out unless absolutely necessary, too emaciated to walk even a short distance. Faint with hunger, many collapsed and died from exposure to the cold. But the need to find food and water still drove people into the streets. The city's water supply was disrupted, so residents collected water from cracks in the asphalt on Nevsky Prospect – the city’s main thoroughfare – caused by artillery fire. More than 2.5 million residents and 500,000 soldiers of the Leningrad front were trapped in the city, with around 780,000 dying of cold and hunger during the first winter of the siege. In a bid to boost morale, the municipal authorities attempted to hold some semblance of new year celebrations to usher in the year 1942. This was considered particularly important for the tens of thousands of children who had not been evacuated from Leningrad in time. Despite the shortage of fuel, a thousand fir trees were brought to the city from nearby forests to be erected in schools, kindergartens, theatres and houses of culture. Plays and performances were put on – even though they were often interrupted by air raids and children had too little energy to follow what was happening on the stage. But everyone was glad for the holiday and especially for the opportunity to get a hot meal after the show. “First, they showed us a concert, then they gave us soup – several noodles in a bowl of almost clear water – and vermicelli with a cutlet for the main course,” one schoolboy recalled. “Since I was so very skinny, they divided one extra portion between me and another equally skinny boy. Apparently, someone could not make it to school and there was a spare portion... After that new year party, I began to somehow get out of my nearly dying state, that get-together and the meal saved me.” “The piece of bread turned out to be small, weighing no more than 50 grams. A better gift could not have been imagined. The boys understood it and treated a piece of bread as the most precious delicacy. Bread was eaten separately from lunch dishes, as everyone tried to savour it for as long as possible,” another schoolboy remembered. A factory foreman described another festive event in the besieged city. “Polina baked one potato peel cake for each of us. I have no idea where she managed to get the peel from. I brought two cubes of wood glue, from which we cooked aspic and there was a bowl of broth for each of us. In the evening, we went to the theatre and watched a production. But it was not much fun, it was as cold inside as it was outside and all the spectators were covered in hoarfrost.” A new year miracle was the appearance of tangerines, sent from Georgia especially for the children of Leningrad. A truck transporting the exotic fruit along the ice road on Lake Ladoga came under fire from two Messerschmitts. Their bullets hit the radiator and the windshield and the driver himself was wounded in the arm, but he managed to deliver his precious cargo. When the truck was examined afterwards, there were 49 bullet holes in it. But not everyone could work up a festive mood for the new year. “That was the first time we celebrated the new year that way. There was not even a crumb of black bread and instead of having fun around a Christmas tree, we went to sleep because there was nothing to eat. When, last night, I said that the old year was ending, I heard in response: ‘To hell with this year, good riddance!’ Indeed, I am of the same opinion and I will never forget the year 1941,” one 16-year-old wrote in his diary, not long before his untimely death in February 1942. By the spring of 1942, Leningrad and its remaining residents began slowly to come back to life. Farms were established in the suburbs to grow vegetables, the streets were cleared of rubbish, intermittent electricity supplies resumed in residential districts and some public transport began operating again. This blog post is largely based on an article from Russia Beyond, which you can read here. The Siege of Leningrad is the backdrop for several historical novels, including Ice Road by Gillian Slovo; The Siege by Helen Dunmore and The Bronze Horseman by Paullina Simmons, among others. My final article of this year is also the last in a series I have written in recent months to honour the memories of those murdered at the ravine of Babi Yar on the outskirts of Kiev, Ukraine, 80 years ago. This time, I will end on a forward-looking note, discussing a new, thought-provoking piece of music theatre designed to move, challenge and inspire. In September 1941, the occupying Nazi forces and their Ukrainian collaborators murdered more than 33,000 Jews at Babi Yar over just two days, beginning on the eve of Yom Kippur. In the following two years of Nazi occupation, Babi Yar became the scene of over 100,000 deaths. This year a group of three Ukrainian musicians journeyed deep into their shared history, drawing on survivors' testimonies, traditional Yiddish and Ukrainian folk songs, poetry and storytelling to produce a new music theatre performance – Songs for Babyn Yar (to use the Ukrainian name for the killing site). The production weaves languages, harmonies and cultures to reveal the forgotten stories and silenced songs from one of the most devastating periods in Ukraine’s past and questions how we can move forward. Songs for Babyn Yar features haunting music from Svetlana Kundish, Yuriy Gurzhy and Mariana Sadovska, all originally from Ukraine but now based in Germany. They are ethnically Jewish and Russian Orthodox and between them perform in Ukrainian, Russian, English, German, Yiddish and Hebrew. Artistic director Josephine Burton, from the British cultural charity Dash Arts, has helped, in her words, “to tease out a narrative that will encompass this shared joy in each other, whilst not shrinking away from the darkness and the horrific tragedy at its heart”. In an interview with the London-based Jewish Chronicle in November, Kundish described the deeply personal link she feels to Babi Yar thanks to a 94-year-old survivor among the congregants of the synagogue in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony - where she serves as the first female cantor - and the close friendship they formed. When the Nazis occupied Soviet Ukraine in the summer of 1941, 13-year-old Rachil Blankman’s parents sent her away from Kiev to Siberia with a sick aunt, while they stayed behind to wait for Rachil’s missing brother to come home. The family that she left behind in Kiev were murdered at Babi Yar. The orphaned teenager eventually returned to Kiev and struggled through many years of hunger and of poverty, but eventually gained a university degree and became an engineer. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Rachil moved to Germany. “Her whole life story is a statement that despite everything, she found a way not only to survive, but also to live a happy life,” Kundish says. Rachil represents the “main voice” of Songs for Babyn Yar. “We have excerpts from the story of her life incorporated into the body of the show, so her voice comes in and out at certain moments, and the music is in a dialogue with her memories,” Kundish says. The willingness in Ukraine today to recognise the atrocities committed at Babi Yar, with major research projects and a new memorial centre underway (which I have written about here) contrasts sharply with the Soviet era, when Jewish memory and culture were all but erased. The Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was banned from reading his 1961 poem Babi Yar (which was later used by the composer Dmitry Shostakovich in his 13th symphony) in Ukraine until the 1980s. And Lithuanian soprano Nechama Lifshitz was barred from performing in Kiev after she sang Shike Driz’ Yiddish Lullaby to Babi Yar at a concert in the city in 1959. Kundish hopes that Songs for Babyn Yar will reach out to as wide an audience as possible and will be part of an ongoing conversation. “I want [people] to tell their children or grandchildren about it. I want them to keep the memory alive because this is a hard chapter of history and it should not be forgotten. And people who live in Ukraine, especially the young generation, they should know about it…I want it to be broadcast on Ukrainian television. I want people to accidentally push the button and end up on this channel and just listen. That’s what I want.” Songs for Babyn Yar debuted at JW3 in London on 21 November 2021 and will be performed at Theatre on Podol in Kiev on 7 December. A short extract is available on YouTube.  Until I was asked, a few weeks ago, to lay a wreath of white poppies at this year’s ceremony of remembrance in our local village, I hadn’t been aware of the symbolism of the white poppy. Unlike the red poppy, it commemorates all victims of war, civilian as well as military, in conflicts past and present, anywhere in the world. White poppies also symbolise a commitment to peace and challenge efforts to glamorise or celebrate war. Victims of war of course include not just those killed during conflict. They include all those who are wounded, bereaved or lose their homes and livelihoods, or live with the daily fear of stray bullets or explosions. They include refugees forced to flee their homes, those who undertake terrible journeys to try to reach a safe haven, who may find themselves held in camps in terrible conditions, locked up in detention centres abroad, or are made to feel unwelcome in the communities where they seek to make a new life. Today’s victims of war include girls in Afghanistan who have been forced to give up their education, all those suffering in war zones in Syria, Yemen, Ethiopia, and many others. My children laid our homemade wreath of white poppies to honour the memories of two members of our own family in particular. The first is my grandmother’s cousin Moishe (pictured left). He was 16 in the summer of 1941 when the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union where he lived. With his mother and younger sister, he fled his home town of Kiev just ahead of the advancing German army, heading east and finding refuge in the city of Kokand in Uzbekistan. On arrival, they found the city already overcrowded with evacuees and they lived in dreadful conditions, amid starvation levels of hunger and epidemics of typhus and other diseases. In 1943 Moishe was called up to a Soviet military academy in Turkmenistan. Then in 1944, he was transferred to the front – to Poland. He died on 16 October 1944, ahead of the Soviet Red Army’s final offensive to liberate Warsaw. He was 18 years old. But fleeing to Uzbekistan enabled Moishe’s mother and sister to escape almost certain death. Six million Jews like them were murdered by the Nazis during World War II. In much of Soviet Ukraine, the Nazis didn’t force Jews into ghettos and transport them to concentration camps, to the gas chambers, as they did in other parts of Europe. Instead, they rounded up the Jews and forced them to pits on the outskirts of towns and villages. In these pits, hundreds of thousands were shot by the Nazis and their Ukrainian collaborators, in what is now referred to as the Holocaust by Bullets. But this wasn’t the only means of mass murder that the Nazis used in Ukraine. Our white poppy wreath also honours the memory of another of my grandmother’s cousins, Baya (pictured right). Baya and my Grandma grew up together. They were both orphans and were brought up by their grandparents in a village about 60 miles from Kiev. When my Grandma and most of her family managed to escape to the West in the 1920s – to Canada – Baya was the only member of the household who chose to stay behind. She was engaged to be married and was studying at university in Kiev. In 1941, when the Nazis invaded, Baya and her husband didn’t flee to the east. They stayed in Kiev, where they were among a group of Jews forced aboard a boat on the Dnieper, the river that cuts through the centre of the city. The boat was set alight. There were no survivors.  I and others in the media have written much in recent weeks about the atrocities committed at Babi Yar, the ravine on the edge of Kiev where Nazis murdered nearly 34,000 Jews in late September 1941. The 80th anniversary of the massacre, and controversy over a new memorial museum to commemorate those who perished, have focused attention on Nazi crimes in Ukraine like never before. The participation of the local Ukrainian police in mass shootings, including those at Babi Yar, is well known and well documented. The usual perception is that a vast majority of Ukrainians were anti-Semitic and supported the German occupiers in their endeavours. I recently came across a fascinating paper by Crispin Brooks, curator of the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, based on his presentation at a conference for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2013. The Los Angeles-based Shoah Foundation was founded by film director Steven Spielberg to preserve on videotape (and later digitise) the first-hand accounts of surviving Holocaust victims – Jews, Roma, political prisoners, Jehovah’s Witnesses, homosexuals and survivors of Nazi eugenics policies – as well as those of other witnesses, including rescuers, liberators and participants in war crimes trials. In Ukraine alone, the Shoah Foundation conducted more than 3,400 interviews from 1995 to 1999, while around twice that number took place in the US, Israel and elsewhere with interviewees born in Ukraine. The overall portrayal of the local Ukrainian police in testimonies is overwhelmingly negative and backs up our knowledge of collaboration by Ukrainians. For example, the following account from Simon Feldman in Boremel, western Rivne region. On Friday afternoon, that particular day, which was two or three weeks after the invasion, they took my father out and nine other men to the Polish church, kościół …, and they shot all ten of them. And the ones that did the shooting, and the ones that did the arresting, and the ones that carried out these atrocities were not Germans. This was the local Ukrainian police. I’m sure that it was under German orders or with the German sanction. But testimonies also show that Ukrainian police officers could be lax when guarding Jewish ghettos, and were often bribed. And there are occasional accounts of a member of the local police assisting Jews, including a Ukrainian policeman who was a friend of the interviewee’s father transporting the family on his cart to safety in return for their remaining possessions. Iulii Rafilovich, a survivor from Bar in Vinnytsia region talked about the role of Ukrainians in the local administration established under German occupation. The Ukrainians mostly had a narrow outlook. They didn’t get involved—“none of our business.” Many were sympathetic. But there were many beasts―the police in particular—and all these beasts rose to the surface. This was especially true of the intelligentsia. I went to the second school, a Ukrainian school. My class teacher Kulevepryk … became the head of the uprava. The history teacher became the editor of the fascist newspaper, Bars’ki visti. Zinaida Ivanovna, the Ukrainian language teacher, became some big shot. And, of course, they treated the Jews terribly. Another testimony describes how after the Jews were massacred in Tomashpil, Vinnytsia region, the head of the Ukrainian community ordered Jewish houses to be demolished for firewood. And yet he hired a surviving Jewish woman to cook for him, thus protecting her. She was just one of many Jews to find protection among Ukrainians. Perhaps surprisingly, given our common knowledge of anti-Semitism in Ukraine both historically and in the present day, the Shoah Foundation conducted 413 interviews with rescuers in Ukraine, more than in any other country. Many survivors talked about being hidden by Ukrainians, and in some instances a single person may have been helped by several different individuals or families on differing occasions. Motivations for offering help were many and varied. For some, it was simply an opportunity for financial gain, while others acted out of humanity or, most commonly, religious conviction. Lidiia Pavlovskaia, a Baptist, recalled her family and neighbours hiding Jews in Boiarka, Rivne region. My father had always taught us and himself believed that Jews were God’s people. And we as evangelical Christians were God’s people, too. So the people who came were like brothers to us. Thus, we had to hide our brothers. We were all in danger of capital punishment, because they would kill all of us [had they found the Jews]. My father, though, believed God would protect us. Perhaps the best known protector of Jews in Ukraine was Metropolitan Andriy Sheptytskiy, Archbishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic church, the only church leader in Nazi-occupied Europe to speak openly in defence of persecuted Jews. Sheptytskiy instructed his clergy to help the Jews by hiding them on church property, offering them food, and smuggling them out of the country. He succeeded in harbouring more than 100 Jews and, unsurprisingly, features in several of the testimonies. Kurt Lewin’s father was Lviv’s chief rabbi and knew Sheptytskiy before the war, which helped him find shelter in various monasteries. Lewin recalled: - Some [monks] were [antisemitic] … They didn’t like Jews. - Did they know you were Jewish? - Yes. - Were you ever betrayed, or did you think you would ever be betrayed? - No … no. You see, the fact they liked or disliked Jews had nothing to do [with it]. They resented the fact Jews were being killed. They resented the bestiality, and they tried to help. Because they felt, within their limited circumstances, they couldn’t in their conscience sit quiet on the sidelines. Some objected to having Jews in the monastery, quite openly … They said so. They said the community was being endangered. But they never betrayed a Jew, you see, never interfered with it. A full copy of the paper can be found here: https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20130500-holocaust-in-ukraine.pdf |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed