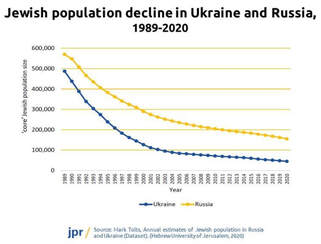

Since February 2022, more than six million Ukrainians have fled abroad in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Another 8 million are internally displaced, mostly in western Ukraine. And around a million Russians have also escaped abroad, many because of their opposition to the war or to avoid the draft under Russia’s partial mobilisation. Among these numbers are tens of thousands of Jews. According to Israel’s Ministry of Aliyah and Integration, more than 40,000 immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus in the year to February 2023. Many members of the Ukrainian Jewish community have also found refuge in other European countries, but those who arrived in Israel held an advantage in having an immediate right to citizenship. The number of Ukrainians with at least one Jewish grandparent – and therefore qualifying for Israeli citizenship by Israel’s Law of Return – was 200,000 in 2020, according to the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR), while the number who identify as Jewish (the ‘core’ Jewish population) was estimated at 45,000. Since the end of the Cold War, the Jewish population of Russia and Ukraine has fallen by 90%, according to the JPR, continuing an exodus that had begun in the early 1970s. An easing of the ban on Jewish refusenik emigration from the Soviet Union at that time allowed approximately 150,000 Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a further 400,000 departed, with more than 80% heading to Israel and the remainder mostly to Germany and the US – several members of my own family among them. In 2014, the number of Ukrainian Jews immigrating to Israel jumped by 190% in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine. Jewish emigration from Russia also spiked and the numbers coming to Israel from both countries stabilised at this higher level in the eight years leading up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With another war now raging in the Middle East, some of those displaced by the hostilities in Ukraine have had to flee twice over. Among them are more than sixty children from the Alumim children’s home near Zhytomyr in western Ukraine. Some are orphans from the surrounding towns and villages within the historic Pale of Settlement, others have parents who are unable to provide a stable home for them. On 24 February 2022, bombs began to fall around the home, which was located close to a Ukrainian air base. Its founders, Rabbi Zalman Bukiet and his wife Malki, had made advance preparations in case of a Russian attack and were able to quickly evacuate the children to the west of the country by bus. After a few days, when it became clear that the war would not reach a swift conclusion, they crossed the border into Romania and from there boarded a plane to Israel. The logistics of the transfer were complex as almost none of the children had passports. Some of their mothers and other community members joined the group until it numbered 170 people. “El Al Airlines wanted us to finalise the number of seats we needed, and the paperwork was an open question,” Rabbi Bukiet recalled. One child had been away visiting his home village when the war broke out and had to be driven to Romania by taxi for a fare ten times higher than the standard rate. Once in Israel, the group was hosted at the Nes Harim education centre in the Jerusalem Hills. “We came for a month and stayed for six,” Rabbi Bukiet said. But as the new school year came round, he needed to find a more permanent home for the children. The group moved to Ashkelon, a coastal town in southern Israel, and rented two accommodation buildings – one for girls and one for boys – as well as apartments for the 16 families that had come with them from Zhytomyr and a home for the rabbi and his own family. “And so Ashkelon became home. The kids learned Hebrew, gained Israeli friends and integrated into the local community. The mothers took jobs and learned to navigate life in Israel. And we all got used to the new normal,” Rabbi Bukiet said. He and Malki arranged visits for a family member from Ukraine for each child, along with outings and activities. With the next school year due to begin, the group decided to stay another year in Ashkelon. Until history repeated itself. On 7 October the sirens once again blared at six am, just as they had in Zhytomyr 18 months or so earlier. Once again, the sound of gunfire and explosions reverberated around them. Rabbi Bukiet and his own family ran to a shelter but were unable to reach the children’s dormitories until midday. By the afternoon, the constant sirens had eased the he and Malki were able to gather the children together in a larger shelter. That night they made plans to relocate again, further north into Israel. Today the inhabitants of the children’s home are based in the Hasidic village of Kfar Chabad, not knowing how long they will stay. Safe for now, their future is uncertain once again. The full story of the Alumim children's home can be found here: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/6186434/jewish/How-Our-Childrens-Home-in-Ukraine-Was-Uprooted-Again-by-War-in-Israel.htm

0 Comments

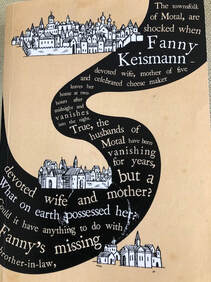

I was invited to give a presentation at a Christian-Jewish church service with a theme of persecution and immigration, as part of this year’s North Cornwall Book Festival. The recent horror of refugees trying to flee Afghanistan in the wake of the Taliban victory, and the plight of migrants making perilous sea crossings in an attempt to reach Europe or the UK, have once again brought these issues to the fore. My own family lived through the pogroms, a series of anti-Semitic riots that took place in the Russian Empire, which in many ways served as a precursor to the Holocaust. Today, we would probably call the pogroms a form of ‘state-sponsored terrorism’ against Jews – supported and incited by the government, if not actually perpetrated by it. They began in 1881, when Jews took the blame for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, and continued in waves for the next 40 years, peaking in 1905 before coming to a head during the Russian Civil War – a chaotic and intensely violent period that lasted for about four years following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. During the civil war, the area where my family lived – near Kiev, in present day Ukraine – became a battleground with numerous armies criss-crossing the land – Communists, Nationalists, Anarchists, anti-Bolsheviks, peasant militias – all of them anti-Semitic to a greater or lesser degree. The White Army in particular, which was loyal to the Tsar – and backed by the West – introduced methods of mass murder of Jews that were later taken and pushed to their limit by the Nazis twenty or so years later. Many White Army soldiers later went on to join the Ukrainian militias that collaborated with the Nazis to destroy all Jewish life in Ukraine in the early 1940s. As well as the violence during the civil war, there was hunger. Food had become scarce during World War l, inflation soared making what little there was unaffordable, and the Bolsheviks requisitioned grain from the countryside (including from my great-great grandfather, who was a grain trader), to feed the workers in the towns. Not only did they take the grain, but also the seed, leaving the peasants with nothing to grow crops with the following year. The population was left to starve. My grandmother Pearl was around 17 years old at the start of the civil war, and an orphan. She lived with her grandparents, siblings and cousins and took it upon herself to become the family breadwinner, undertaking terrifying and dangerous journeys by train to markets across the region to buy, sell and barter what she could to keep her family alive. Eventually she even became a black-market gold dealer – taking any gold items belonging members of her local community on a murderous journey half way across Ukraine to exchange them for hard currency, which she brought back to the villagers so they could use it to buy food. Had she been caught, either with the gold or hard currency, she would have been shot. After more than three years of this perilous life that she hated with a passion, and following a particularly arduous trading trip when she was caught in a snowstorm and almost froze to death, she could take it no more. She decided she must try to get herself and her family out of the country. Six months later, in 1924, Pearl managed to emigrate to Winnipeg, Canada to join some other members of her extended family who had already made it out of Russia. She travelled alone, and with nothing. Once in Canada she did what so many immigrants do. She found a job and worked hard, scrimping, saving, and borrowing to raise enough money to bring the rest of her family over to join her the following year. Today my family is spread across Canada, from Vancouver to Toronto, and in America from California to New York, as well as in Germany, Israel and the UK, where they became, among other things, teachers and lawyers, journalists and doctors, Rabbis and social workers, all adding in their own unique ways to the prosperity and cultural life, as well as the wonderful diversity, of the places they now call home. Photo: Pearl (left) with her sisters Sarah (centre) and Rachel, circa 1920  The Gulag was the largest network of forced labour camps ever created, spanning thousands of miles across the Soviet Union. Around 18 million prisoners, possibly more, were sent to the Gulag from 1930 to 1953 during the rule of Joseph Stalin, of whom up to three million died in the camps or as a result of their incarceration. As well as criminals, the Gulag became home to huge numbers of political prisoners. One of these was Yehuda Solomonovich Kaufman, the husband of my great-grandfather’s sister Miriam (Mira) – whose story I have been telling in my blog over the last few weeks – and grandfather to my cousin Irina (Ira), who has shared her family stories with me. Yehuda, originally from the town of Bobruisk in today’s Belarus, was arrested no less than three times before finally being sent to the Gulag in 1938. The first was in the 1920s when he was arrested as a Jewish nationalist because he gave private Hebrew lessons, in addition to his professional work as a surgeon. His next arrest came in 1931, this time because he corresponded with several members of his family (brothers, a nephew) who lived abroad. He was sent to prison, missing the birth of his daughter Sulamia as a result. In 1936-37 Yehuda’s nephew came to Kiev from overseas to visit, and after this he was arrested for a third time and sentenced to ten years in a labour camp in Krasnoyarsk region as an ‘enemy of the people’. Although conditions were harsh and his sentence was long, he was lucky in being able to work as a doctor, and like many inmates, he even had a ‘prison wife’. In 1949 Yehuda was finally permitted to return to Kiev. He left his prison wife to return to Mira, but no sooner had he set foot in his apartment for the first time in more than a decade than a group of state security agents arrived to arrest him once again. Rather than sending him back to the Gulag or to Siberia, he was exiled to the town of Zvenygorodka in Cherkasy province, central Ukraine, where he remained until his eventual release in 1956. Ira, who was born in 1952, recalls that as a little girl, her family told her that Grandpa was “in Paris”. But later she remembers visiting him in Zvenygorodka, in a room with a round table and a bed with springs, which she would use as a trampoline. Stalin died in 1953, and the Soviet reign of terror came to an end. But the truth of the labour camps, the mass deportations, executions and purges did not become public until Nikita Khrushchev cemented his place at the head of the Communist Party in the power struggle that followed Stalin’s death. Khrushchev’s so-called ‘secret speech’ to party officials in February 1956 denounced Stalin’s excesses and heralded a period of liberalisation, during which thousands of prisoners - including Yehuda – were set free and rehabilitated. Once he was finally back in Kiev after 18 years of separation from his family, Yehuda managed to return to his work as a surgeon and to put the experiences of the previous two decades behind him. He was a cheerful man, loved by friends, family and colleagues alike, who rejoiced in his family and in life in general. He built up a strong relationship with his daughter in spite of their long years apart, and doted on his grandchildren, giving them little presents every day. He even wrote stories about his childhood that he illustrated himself. He died in 1964. Although life improved for the people of the Soviet Union under the so-called ‘Khrushchev thaw’, the discrimination and anti-Semitism that hounded Jews first under the Tsars and then under the Communists did not go away. Religion had been abolished after the October Revolution of 1917, so Judaism was no longer considered a religion but a nationality, marked in Soviet passports on the personal details page under the notorious point number five: Национальность – Eврей (Nationality – Jewish). This opened Jews up to any and every form of discrimination and anti-Semitism, from being humiliated in the street and called a Yid, to being marked down in exams, denied a place at university, overlooked for a promotion. So Jews kept quiet about their ‘nationality’. Parents were afraid to teach their children Yiddish, to follow the traditions that their people had lived by for thousands of years, to celebrate the Jewish holidays, and so the Yiddish language and Jewish customs died out, although small pockets remained in smaller towns and rural communities. “We were a typical Soviet family,” my cousin Ira says. “Nothing remained of our Jewishness except our surname and an entry in our passport.” As a child, she and her sister Mila wanted to blend in, to be like everyone else. Their parents didn’t talk to them about their ‘nationality’, nor later did they ever discuss it with their children. It wasn’t until the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 that Jews were permitted to emigrate, in a bid for freedom from discrimination. Hundreds of thousands left, mostly for Israel, but also for the United States and Germany, where Ira and her family now live.  Most Jews in North America and much of Europe can trace their roots back to the Russian Empire, once home to the world’s largest Jewish population. But how many of us actually understand how our families ended up there in the first place? The basics are fairly well known. After the Roman sacking of Jerusalem in 70AD, Jews scattered across the Roman Empire, which covered most of southern and western Europe and north Africa. By the time of the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 4th and 5th centuries, the Jewish diaspora had spread right across Europe. The split into two distinct communities: the Sephardi on the Iberian Peninsula and the Ashkenazi along the Rhine in Germany occurred around the 10th century. During the Crusades in the 13th-15th centuries, Jews were expelled from much of western Europe, including from England in 1291, France in 1343 and much of western Germany in the early 15th century. Many fled east, to the one country that offered a safe haven for Jews – Poland. Here King Casimir the Great (reigned 1333-1370) welcomed Jews for their trades and skills and protected them as “People of the King”. But by the 18th century, Poland was a weak and failing state, preyed on by its more powerful neighbours: Prussia, Austria and Russia. These three great European powers divided the country up between them in the three Partitions of Poland of 1772, 1793 and 1795. The area to the southwest of Kiev where my family came from became part of the Russian Empire under Catherine the Great in the second partition of 1793. Since 1991 it has been in independent Ukraine. Bert Shanas, a retired journalist turned genealogist from New York, has traced his family history to shtetls southwest of Kiev from at least the mid-1600s, and it is from his research that I have borrowed the contents and title of this article. The typical Ashkenazi Jew from this region, Shanas says, has an ancestral line that began in Africa, migrated to the Middle East, and from there into Europe, through France, to present-day Germany and into Poland, to an area that went on to become Russia then Ukraine over the course of some 200,000 years. Using a combination of DNA testing, recent scientific studies, archaeological discoveries, and biblical and historical scholarship, Shanas has traced the likely route his ancestors would have taken. His male family line would have had its origins in east Africa 60,000-70,000 years ago – around present-day Ethiopia, Kenya or Tanzania. Major climatic changes would probably have forced his ancestor to journey to the northeast in search of an adequate food supply, most likely travelling in a group of around 200 people. They would have crossed the Red Sea – then a smaller, shallower channel – into present-day Saudi Arabia and continued eastwards along the coast of the Arabian Sea until they reached the Indus Valley, the area that is today Pakistan. Thousands of years later, it is likely his ancestors would have broken off from the group and headed north through Iran to settle in what is now Turkey, around 40,000 years ago. About 10,000-15,000 years ago, they would have moved on to the Middle East, where Jewish history began – with Abraham, who came from the city of Ur in Babylonia, now southern Iraq - around 3,200 years ago. Shanas believes that following the Roman conquest of Jerusalem, his ancestors would probably have travelled from the Middle East through Turkey, Greece and Italy, then north through France around the year 1400 and from there to Germany. Around 1500, they would have moved east again, into Poland and by 1600-1700 were settled in the area near Kiev. DNA analysis indicates that Shanas’ female family line probably ended up in Poland by a different route, trekking north from the area around present-day Kenya or Ethiopia around 60,000 years ago, through Sudan and Egypt into the Middle East. They would have survived the last Ice Age somewhere around Mediterranean Europe and once the glaciers retreated, spread throughout Europe between 10,000 and 20,000 years ago. His ancestral line would probably have migrated to the Caucasus mountains then arced over the Black Sea into the Balkans. From there the DNA trail branches in two directions, the first heading north into Finland, passing through Poland on the way, and the second going west along the Mediterranean through France and Spain, into Portugal. DNA analysis shows that his genetic female ancestors were not grouped in great numbers in any one spot, but were scattered across eastern and western Europe, and their exact route to Ukraine is unclear. A study of the origins of Ashkenazi women by Professor Martin Richards at the University of Huddersfield in the UK and cited by Shanas in his research, found that in at least 80% of the cases studied, the DNA of Jewish women traced back to Europe – unlike that of men, which traced back to the Middle East. Richards concluded that the vast majority of Jewish men who fled the Middle East for Europe after the Roman conquest did not take women with them. Instead, they married local European women, who then converted to Judaism. With grateful thanks to Bert Shanas for allowing me to use his research for this article. As another lockdown Passover begins, I’ve been reflecting on this Passover story that dates back nearly a century, to the late 1920s. My great-grandmother’s cousin Babtsy arrived in Winnipeg, Canada, with her husband Moishe and four children at the end of their long journey from Kiev, which at that time had recently become part of Soviet Ukraine. Babtsy and Moishe had survived a terrible pogrom in their home town of Khodorkov in 1919. The town’s Jews had been rounded up and herded to a sugar beet factory beside a lake, then forced to keep going deeper into the lake until they drowned or froze to death. Babtsy and her family had hidden in a basement and, when it was safe to emerge, they found houses smouldering around them and the lakeside littered with pale corpses. Barely stopping to grab a handful of belongings, they fled to the railway station and took the first train to Kiev, where they remained for several years, living with Moishe’s parents. Owing to a mixture of errors, misunderstandings and delays, it took three and a half years from the time they first lodged their application to emigrate to Canada to their eventual arrival in Winnipeg. Remarkably, our family has around 50 pages of documentation relating to this process, consisting of letters between the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society Western Division in Winnipeg, its head office in Montreal, and the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization in Ottawa. I have written about this in a previous article, which you can read here. Once Babtsy, Moishe and their children finally arrived at the Canadian Pacific Railway Station in Winnipeg, they asked the station master to call the phone number of Babtsy’s cousin Faiga. Faiga had been the first member of our family to leave the Russian Empire for Winnipeg back in 1907 with her husband, Dudi Rusen, and one of her brothers. Dudi was an ambitious young man. Once in Winnipeg he bought a pushcart and based himself on a street corner to sell fruit and vegetables. He worked hard and after a while had raised enough money to buy a truck, then within a few years he was running his own wholesale produce company. Faiga and Babtsy had not seen one another for more than 20 years. Faiga and Dudi, with their children and grandchildren, were in the middle of a Passover Seder when the station master rang on that spring evening. Dudi answered the phone and told him to put the newly arrived family in a taxi and send them straight to his home at 107 Hallett Street. To great excitement, everyone budged up around the table to make space for the relatives from the Old Country so they could join the Seder, and celebrate this latest escape of Jews, to a new Promised Land, alongside the ancient exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. This Passover story is narrated in the following clip by Monty Hall, the host of TV’s Let’s Make a Deal. Monty was Faiga and Dudi Rusen’s grandson and was at their house that evening during Passover. In the video, Monty describes his tremendous excitement at reading my book, A Forgotten Land, and discovering that it was about his own family. Monty contacted me after he read the book and we had a long telephone conversation, during which he recounted this Passover story to me. After many years hosting Let’s Make a Deal, Monty Hall engaged in philanthropic work, helping to raise close to a billion dollars for charity. He features in both the Hollywood and Canadian Walk of Fame, and the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs, California, and was awarded the Order of Canada in 1988. He died on 30 September 2017 at the age of 96.  Antony Blinken is on the cusp of being appointed Secretary of State in the new administration of President Joe Biden. One thing many people may not know about Blinken is that his great-grandfather was a Yiddish writer of some repute. Meir Blinken was born in 1879 in Pereyaslav, Ukraine – coincidentally the same shtetl as Yiddish literature’s most famous name, Sholem Aleichem. Blinken gained a Jewish education at a Talmud Torah, before attending the secular Kiev commercial college, part of a joint educational project founded by Ukrainian and Jewish businessmen. He worked as an apprentice cabinet-maker and carpenter, before switching to become a massage therapist. Indeed, he is listed in the Lexicon of Modern Yiddish Literature with the trade of masseur. His son Moritz, Tony Blinken’s grandfather, who became an American lawyer and businessman, was born in Kiev. Blinken Senior emigrated to the US in 1904. His first story, written under the pen-name B Mayer, was published a year earlier, in 1903. Once in America, his sketches and stories appeared in a range of literary, progressive socialist and labour Zionist publications, including the satirical magazine Der Kibetzer (Collection) and Idishe Arbeter Velt (Jewish Workers’ World) in Chicago. In all, he published around 50 works of fiction and non-fiction. Blinken’s books include Weiber (Women), described in the lexicon as a prose poem, Der Sod (The Secret) and Kortnshpil (Card Game). A collection of his short stories published in 1984 and translated by Max Rosenfeld, is still available. His writing dealt with thorny topics including the effects of poverty, poor living conditions, religious strictures, inadequate education and the lack of understanding that immigrants feel about their new country. Most controversially, he was one of the few male Yiddish writers to address the subject of women’s sexuality, writing about marital infidelity and sexual desire and hinting at the sense of boredom felt by housewives. Another subject he tackled remains controversial to this day: showing empathy towards abortion. Writing in a review of Blinken’s work in the 1980s, the journalist and author Richard Elman pointed out that among Yiddish authors writing for the largely female audience of Yiddish fiction, Blinken “was one of the few who chose to show with empathy the woman’s point of view in the act of love or sin”. Elman and others believed that the greatest legacy of the author’s work was that it vividly evoked the atmosphere and characters of the very early Jewish diaspora in New York. According to a 1965 article by the journalist David Shub in the Jewish newspaper The Forward, Blinken was the first Yiddish writer in America to write about sex. In the same article, he wrote that Blinken was also an editor’s nightmare! By the time of his death in 1915 at the age of just 37, Blinken had opened an independent massage office on East Broadway, in the heart of what was at that time the city’s Yiddish arts and letters district. While his writing was very popular among Yiddish-speaking Americans of his own generation, Blinken’s star quickly waned after his death. Photo credit: Ukrainian Jewish Encounter  One of the most original and unusual books I’ve read in a long time is The Slaughterman’s Daughter by Yaniv Iczkovits, a recent release, translated from the Hebrew, from the always impressive MacLehose Press – a UK publisher that specialises in works in translation. Set in the Pale of Settlement of Imperial Russia at the end of the 1800s, it tells the story of Fanny Keismann, the eponymous daughter of a kosher butcher, who goes in search of her brother-in-law, Zvi-Meir, after he abandons her sister and their two children. Fanny’s journey to Minsk – now the capital of Belarus and recently in the news for mass protests against its tinpot dictator Alexander Lukashenko who refuses to give up power – is fraught with danger. Fanny’s talent with a butcher’s knife stands her in good stead to quell her foes, but it also sets in train a fantastical series of events that spiral out of control and, unsurprisingly, get her into trouble with the law. Like the stories of Sholem Aleichem, this book and its cast of motley characters evokes a nostalgia for the shtetls of Belarus, Ukraine and elsewhere in the region before the Russian Revolution, and a way of life that was already beginning to unravel when this novel was set. Hundreds of thousands of Jews had begun to emigrate to the west (mostly the United States) in search of an escape from discrimination, anti-Semitic violence and economic hardship from the 1880s onwards. Later, of course, during the Nazi occupation of 1941-44, the shtetls were destroyed altogether, their inhabitants murdered or, in the case of a lucky few, forced to flee eastwards in a bid for survival. It is impossible not to feel a deep regret for the disappearance of these vibrant communities where our ancestors lived for generations, settlements that were extinguished so brutally. I for one am fascinated by stories and images of the lost Jewish world of Eastern Europe. But the shtetls were home to a way of life that was tough and unenviable, as this novel demonstrates. They were generally poor, miserable places, where, “The Jews have huddled so close to each other that they have not left themselves any space to breathe”. And where Jew and Goy often distrust one another absolutely. For most of us with origins in the kinds of places that Iczkovits writes about, when we think of this period of history what we remember are the pogroms – the brutal anti-Semitic violence that broke out periodically in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This book, filled with black humour and deep affection, but also gritty realism, provides a wonderful illustration that there was much more to this time and place. The author describes a way of life where, outdoors, “The market is a-bustle with the clamour of man and beast, wooden houses quaking on either side of the parched street. The cattle are on edge and the geese stretch their necks, ready to snap at anyone who might come near them. An east wind regurgitates a stench of foul breath. The townsfolk add weight to their words with gestures and gesticulations. Deals are struck: one earns, another pays, while envy and resentment thrive on the seething tension. Such is the way of the world.” Meanwhile, indoors, mothers share a bed with their multiple children and face continual curses and criticism from their in-laws in the next room, who treat them like servants. Yaniv Iczkovits is an Israeli born of Holocaust survivors. “What I wanted to do was to bring these forgotten memories of this lost world into 21st century Israel, and to present the richness of a culture that is now gone, but is still a major part of who we were and what we are,” he says.  My second and final post based on the publication A Journey through the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter looks at issues of assimilation and emigration. The Journey is a fascinating document published last year by a private multinational initiative called Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter aimed at strengthening mutual comprehension and solidarity between Ukrainians and Jews. Jewish assimilation in the Russian Empire wasn’t necessarily a question of choice. The government of Tsar Nicholas I enacted measures to refashion and forcibly assimilate the Jewish population. In 1827, it ordered a quota system of compulsory conscription of Jewish males aged 12 to 25 (for Christians it was 18 to 35) to the Tsarist army and made the leadership of each Jewish community responsible for providing recruits. The selection process was often arbitrary and influenced by bribery, turning Jews against their communal leaders. By 1852–55, so-called happers were tasked with kidnapping Jewish boys, sometimes as young as eight, in order to meet the government’s quotas. As described in my book, A Forgotten Land, the happers spread fear across the Pale of Settlement. Once conscripted, the young Jewish recruits were pressured to convert to Russian Orthodoxy, with the result that around one-third were baptised. The drafting of children lasted until 1856. Other assimilationist measures included the establishment of state-sponsored secular Russian-language schools for Jewish children and rabbinic seminaries to train ‘Crown Rabbis’ who were expected to modernise the Jews. An 1836 decree closed all but two Hebrew presses and enacted strict censorship of Hebrew printing. In 1844 the kahal system of Jewish autonomous administration was abolished. Decrees were also passed on how Jews should dress and the economic activities in which they were allowed to engage. The Jewish Enlightenment – an intellectual movement across central and eastern Europe promoting the integration of Jews into surrounding societies – helped to further the aims of the tsarist government. Activists known as maskilim were enlisted to censor Jewish religious books, as these were considered to promote fanaticism and be an obstacle to Russification. A series of laws and decrees improved the situation of the Jews under Tsar Alexander II (1855-81). Conscription requirements became less severe, while some Jews were allowed to reside outside the Pale and to vote. Political and social reforms enabled the first generation of Jewish journalists, doctors, and lawyers to obtain degrees at the state-sanctioned rabbinic seminaries and universities, going on to form the core of a modernised Jewish intelligentsia. Journalists and writers, often from the ranks of the maskilim, began to publish Russia’s first Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian-language Jewish newspapers. Modernist synagogues were established. But state-sponsored discrimination against Jews continued, as did anti-Semitic articles in the Russian press and the expulsion of Jews deemed to be residing in Kiev illegally. The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 triggered a new round of repression, with Jews banned from certain professions and geographical areas, and political and educational rights restricted. Only Jews who converted to Orthodox Christianity were exempt from the measures. By the late 1800s, a small group of prosperous Jewish traders had emerged, but the vast majority of Jews lived a modest existence that often bordered on poverty. According to the Jewish Colonization Society, in 1898 the poor comprised 17-20% of the Jewish population in several provinces of present-day Ukraine. But worse than the grinding poverty and discrimination were the pogroms. Derived from the Russian verb громить (gromit’), meaning to destroy, pogroms were waves of violent attacks on Jews that took place across the Pale primarily in 1881-82, 1903-06, and 1918-21. Alexander II’s assassination triggered mobs of peasants and first-generation urban dwellers to attack Jewish residences and stores. Of 259 recorded pogroms, 219 took place in villages, four in Jewish agricultural colonies, and 36 in cities and small towns. Altogether 35 Jews were killed in 1881–82, with another 10 in Nizhny Novgorod in 1884. Many more were injured and there was considerable material damage. A second wave of pogroms began in 1903 with an outbreak of anti-Semitic violence in Kishinev, in which the authorities failed to intervene until the third day. Further pogroms followed Tsar Nicholas II’s manifesto of 1905 that pledged political freedoms and elections to the Duma. The mass violence was orchestrated with support from the police and the army and carried out by the ‘Black Hundreds’ – monarchist, Russian Orthodox, nationalist, anti-revolutionary militants. Around 650 pogroms took place in 28 provinces, killing more than 3,100 Jews including around 800 in Odessa alone. Jews attempted to resist pogroms in many areas by organising self-defence groups. Many were community-organised, but the Jewish Labour party or Bund also began mobilising self-defence units in the early 20th century. The 1881–82 pogroms set in motion new political and ideological movements, and led to large-scale emigration. For many Jewish intellectuals, the goal of integration and transformation of communities through education and Russification was now discredited. Some perceived socialism, with its promise of equality, as the solution; others promoted emigration to America or Palestine. By the end of the nineteenth century, both Jews and Ukrainians began to emigrate in large numbers, mostly to North America. In 1882 Leon Pinsker, a physician from Odessa who had earlier promoted the integration of Jews into broader Russian society, published an influential pamphlet titled Autoemancipation, in which he advocated that Jews establish a state of their own. He proceeded to found the Hibbat Zion movement, which paved the way for the Zionism. In 1882–84 some 60 Jews from Kharkov moved to Palestine, the first mass resettlement of Jews in Israel. From 1897 Zionist circles were established in several Ukrainian cities, making the region a centre of organised Zionism. The Tsarist government was initially indifferent towards the Zionists, but eventually banned them. According to the 1897 census, 2.6 million Jews lived on the territory of present-day Ukraine. Kiev and some other provinces had a Jewish population of around 12-13%, while in Odessa, Jews made up almost 30% of the population. Of the Jewish population, more than 40% were engaged in trade, 20% were artisans and 5% civil servants and members of ‘free professions’, such as doctors and lawyers. Just 3-4% were engaged in agriculture, in contrast to the vast majority of the Ukrainian population. Given these figures, the scale of emigration was immense. More than two million Jews migrated to North America from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1914, mainly from lands that make up present-day Ukraine. Of these, about 1.6 million came from the Russian Empire (including Poland), and 380,000 from provinces of western Ukraine that were at the time part of Austria-Hungary (mainly Galicia). Another 400,000 Eastern European Jews migrated to other destinations, including Western Europe, Palestine, Latin America, and southern Africa. Jews comprised an estimated 50 to 70 percent of all immigrants to the United States from the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1910. About 10,000 Jews had arrived in Canada by the turn of the century, rising to almost 100,000 between 1900 and 1914, settling mostly in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, the hub of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where my own family settled. Click here to see the document on which this article is based https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/media/UJE_book_Single_08_2019_Eng.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2D2QAuBtjsIqF1kHi4eRUlxBZT-UFPR3usj0741Cp3nnnouJT1icJGphM  I’m very excited to finally be visiting Winnipeg this month, my father’s home town and the place where my family settled when they left Russia for the West. Once my grandmother resolved to leave her shtetl, Pavoloch, in 1924, it took around six months for her great-uncle Menachem Mendl Shnier, who was already in Winnipeg, to prepare the documentation she needed and bring her to Canada. But the process wasn’t always so straightforward. The following year, her Uncle Mendl began the process of getting our remaining family members out – his step-mother Leah (left) and step-sister Babtsy (right, standing) and her family. It was another three and a half years before they finally arrived in Winnipeg. Remarkably our family has the documentation relating to this process, which amounts to some 50 pages and shows a to-ing and fro-ing of letters between the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society Western Division, which is in Winnipeg, and its head office in Montreal, and the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization, in Ottawa. The application, dated 6 October 1925, was filled in by Menachem Mendl Shnier of 125 Euclid Avenue, Winnipeg, and is supported by letters from his grandson ID Rusen, a young lawyer in Winnipeg. The documents give a fascinating insight into the immigration process and officialdom of the time. Part of the reason this application took so long was that Leah’s surname was listed incorrectly – making it appear that she was the mother of Babtsy’s husband, which would have made her ineligible to come to Canada as she was not a direct relative. A letter from the immigration department dated 19 February 1926 says: “I beg to advise that it is evident that Leah Margolis is the mother of Moses Margolis and not the mother of Chaya Margolis, nor would she appear to be in any way related to the applicant or his wife. She therefore does not come within the classes specified in the quota agreement and I regret that no action can be taken by the Department to facilitate her entry into Canada.” The remainder of the family was permitted to immigrate, according to a separate later letter the same month. Their permit was valid for five months, but this period expired while the family tried to correct the mistake and re-add Leah to the application. During this time, the Winnipeg office of the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society asks for a ‘donation’ of $30 “as we have had considerable expense in connection with this permit”. This money wasn’t paid – again presumably because the family didn’t want Leah left behind in what was now the Soviet Union, and a further demand for money was made, which also went unpaid. Eventually, in November 1926, 14 months after the initial application was made, there is a letter from the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society in Winnipeg admitting that it was responsible for the error regarding Leah’s surname. I love the way this letter continues ironically … “Will you kindly endeavour to obtain the necessary permission for the above [meaning Menachem Mendl Shnier] as he is calling at this office every time he goes to "Shul", and being a religious man he goes to Shul four times a day.” Now the immigration department in Ottawa wants to see evidence that Leah is who they say she is, so the family sends a signed affidavit, which the department deems unsatisfactory. They need to provide Ottawa with “documentary evidence from the Russian authorities”. At this point, ID Rusen, the young lawyer, steps in saying that seeing as this was the Jewish Aid Society’s fault, the Society should be responsible for fixing it. But this idea is firmly rejected. Unfortunately, we don’t have a copy of whatever evidence of Leah’s identity is submitted, but finally in March 1928 – two and a half years after the initial application – the family has permission for everyone to immigrate, with Leah now listed correctly as Menachem Mendl’s step-mother. The final letter, written in September 1928, states that by now Leah is almost blind “her left eye having been removed after an operation for cataract, and her right eye being only one percent normal. If this elderly lady's optical disability is as outlined above, her movement to Canada cannot be authorized. However, if satisfactory settlement arrangements are made for her in Russia, there would appear to be no reason why Moses Margolis and family cannot come.” So after all this, three years later, Leah has to be left behind in Russia after all, and the rest of the family finally arrive in Winnipeg at Passover 1929, nearly three and a half years after their application was originally filed. Leah died in Kiev two years later. All the documents are available to view on the Shnier family website www.shniers.com Monty Hall, who died a few days ago, was a distant cousin of mine. Monty was born Monte Halparin in Winnipeg, Canada, in 1921. He rose to fame as host of the game show Let’s Make a Deal and even put his name to the Monty Hall problem, a probability puzzle based on the show. I never met Monty, but apparently my grandmother used to babysit him when he was a baby. My great-grandmother, Ettie Leah, and Monty’s grandmother Faiga were first cousins. They lived next door to one another in a large double-fronted house built by their grandfather in the village of Pavoloch, about 60 miles from Kiev. On the advice of a Rabbi, the house had been divided up by drawing lots, and my side of the family was awarded the larger part of the property. This division of the house caused a great rift between my great-great grandmother Pessy, and Monty’s great-grandmother Bluma. Although their husbands were brothers and remained close throughout their lives, their wives were always at loggerheads and even in old age, a simmering resentment and jealousy continued between them. Faiga and her husband, Dudi Rusen, were the first of our family to emigrate from Russia to Canada in the early 1900s. Dudi was clever and ambitious, and had long dreamed of moving to the West. They settled in Winnipeg. Dudi bought a pushcart and based himself on a street corner to sell fruit and vegetables. Soon he had enough money to buy a truck and within a few years he was running his own wholesale produce company and had bought a handsome house in the best part of town. When my grandmother needed to escape terrible hardship in Russia following the Bolshevik Revolution and Civil War, it was Dudi who lent the money for her journey. My grandmother found a job in a factory to pay him back and try to raise the funds to bring the rest of her family over to Canada, again with Dudi’s help. I’m grateful to another cousin of mine for posting the following clip on Facebook, in which Monty recalls a telephone conversation I had with him a couple of years or so ago. Monty called me after my book, A Forgotten Land, was published. He was tremendously excited by the book and recounted this Passover story to me over the phone. The story relates to Babtsy, my grandmother’s great-aunt, and her arrival in Winnipeg from Russia. Babtsy and her husband Moishe had survived a terrible pogrom in their home town of Khodarkov in 1919. The Jews were rounded up and herded to the sugar beet factory beside the lake, then forced to keep going deeper into the lake until they drowned or froze to death. Babtsy and her family had hidden in a basement and, when it was safe to emerge, they found houses smouldering around them and the lakeside littered with pale corpses. Barely stopping to grab a handful of belongings, they fled to the railway station and took the first train to Kiev, where they remained with Moishe’s family before managing to emigrate some years later.

After many years hosting Let’s Make a Deal, Monty Hall engaged in philanthropic work, helping to raise close to a billion dollars for charity. He features in both the Hollywood and Canadian Walk of Fame, and the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs, California and was awarded the Order of Canada in 1988. He died on 30 September at the age of 96. May he rest in peace |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed