|

Next Monday, 18 March, marks the tenth anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The move followed swiftly on from Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, which culminated in then-president Victor Yanukovych’s flight from Kyiv in late February 2014. Russia took advantage of the chaos in Kyiv, quickly seizing military bases and government buildings in Crimea.

Armed men in combat fatigues began occupying key facilities and checkpoints. They wore no military insignia on their uniforms and Russian president Vladimir Putin insisted the “little green men” – as Ukrainians called them – were acting of their own accord, and were not associated with the Russian army. Only later did he acknowledge the role of the Russian military in the occupation, even awarding medals to those involved. By early March, Russia had taken control of the whole peninsula and its ruling body, the Crimean Supreme Council, hastily organised a referendum for 16 March. The vote went ahead without international observers and was widely condemned as a sham. It offered residents two options: to join Russia or return to Crimea’s 1992 constitution, which gave the peninsula significant autonomy. There was no option to remain part of Ukraine. The result, predictably, was landslide in favour of becoming part of Russia. Turnout was reported to be 83%, with nearly 97% voting to join the motherland, in spite of the fact that Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars made up nearly 40% of the population. The accession treaty was signed two days later. In May that year, a leaked report put turnout at 30% with only half of all votes cast in favour of becoming part of Russia. The annexation of Crimea gave an immediate boost to Putin’s approval ratings, following a turbulent period of pro-democracy protests across Russia in 2011-12. In the face of a weak economy, Putin’s re-election campaign in 2012 had focused on appealing to Russian nationalism, and the swift and bloodless coup in Crimea provided a perfect model for his propaganda narrative. The peninsula had first become part of Russia in the eighteenth century under Empress Catherine the Great, who founded its largest city, Sevastopol, as the home of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Crimea was part of the Russian republic of the Soviet Union until 1954, when it transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet republic. When the USSR collapsed in December 1991, the successor states agreed to recognise one another’s existing borders. Russia’s seizure of Crimea violated, among other agreements, the UN Charter, the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances for Ukraine and the 1997 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Ukraine and Russia. Crimea has experienced significant changes over the past ten years. Ethnic Russians made up around 60% of the population in 2014 — the only part of Ukraine with a Russian majority. Since then, around 100,000 Ukrainians and 40,000 Crimean Tatars are estimated to have left the peninsula, while at least 250,000 more Russians have moved in, pushing the ethnic Russian population above 75%. Many are members of Russia’s armed forces as the Kremlin has built up its military presence on the peninsula. Others are civilians lured by Russian government incentives, such as job opportunities, higher salaries, and lower mortgage rates. Crimean Tatars complain of intimidation and oppression. They are routinely searched, interrogated, accused of terrorism offences and sent to prisons thousands of kilometres away. In prison, they are denied access to medical care, put in isolation cells and forbidden from communicating with relatives or lawyers, or from practising their religion, according to a report in the Kyiv Independent. Of the ethnic Ukrainians who remained in Crimea in the years after annexation, a significant number have since been expelled, imprisoned on political grounds, forced to move to Russia or mobilised into the Russian military. Amid the ubiquitous narrative of Crimea as historically and enduringly Russian, and with public spaces dominated by Soviet and war nostalgia, Crimeans today are afraid to identify as Ukrainian. The high-tech security fence erected on the border between Crimea and mainland Ukraine in 2018 now symbolises separation from family and friends elsewhere in the country. Moscow has poured more than $10 billion in direct subsidies into Crimea, investing heavily in schools and hospitals, as well as military and civilian infrastructure. Crimea today accounts for around two-thirds of all direct subsidies from the Russian federal budget. But many local businesses have suffered, particularly with the decline in tourism, which once accounted for about a quarter of Crimea’s economy. And as Ukrainian products in shops were replaced with higher-priced Russian goods, and later as the value of the rouble fell, prices have spiked. Western sanctions against Russia have also taken their toll on Crimea’s economy. Crimea was one of the Russian regions with the lowest income levels in 2023, according to the Russian state-owned rating agency RIA. Russia has also funded major construction and infrastructure projects, such as the Tavrida highway, which opened in 2020 connecting the east of Crimea with its major cities in the southwest, and the highly symbolic Kerch bridge linking Crimea to Russia, opened to great fanfare by Putin in 2018. Today parts of the Tavrida highway have reportedly begun to buckle, leading to a rise in road traffic accidents. The Kerch bridge has sustained serious damage from Ukrainian attacks and by December last year was still not fully restored. Back in 2014, many Russians in Crimea were euphoric about rejoining the motherland, having always identified with Russian rather than Ukrainian culture and customs. They welcomed the attention that Putin lavished on them, and the influx of Russian cash meant that wages and pensions, now paid in Russian roubles, initially increased. The euphoria has since subsided, and particularly since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many Crimeans are fed up with living in a territory that is isolated, highly militarised, tightly controlled, economically weak and under attack from Ukrainian forces.

0 Comments

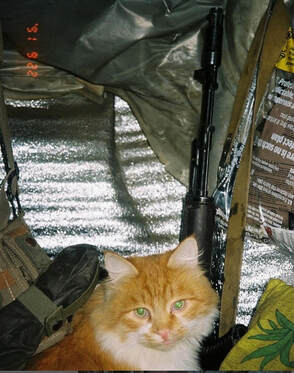

At least 95 Ukrainians known for their work in the creative industries have been killed since Russia’s full-scale invasion began nearly two years ago, according to the writers’ association PEN Ukraine. The organisation tracks losses among writers, publishers, musicians, artists, photographers, actors, filmmakers, and other creative professionals whose stories appear in the information field. It is likely that many more artists have been killed in the war than appear on PEN’s list. On 7 January the poet Maksym Kryvtsov was killed by artillery fire in Kupiansk, near Kharkiv, one of the key fronts in Moscow’s winter offensive. His loyal companion, a ginger cat, was killed with him. Kryvtsov, aged 33, had been hailed as one of the brightest hopes of Ukraine’s young, creative generation. Kryvtsov was an active participant in the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity – better known in the West as Euromaidan – and joined Ukraine’s armed forces as a volunteer in 2014, when the war against Russian separatists in the Donbas region began. He was later involved in organisations helping to rehabilitate fellow veterans and help them reintegrate into society, and also worked at a children’s camp. He was, by all accounts, far from the stereotypical image of a fighter. Kryvtsov returned to army in February 2022 when Russian forces invaded Ukraine. Comrades knew him by his call sign Dali – a reference to the curling moustache he grew in imitation of the Spanish artist Salvador Dali. “I think the war is a kind of micellar water that washes cosmetics off: from a face, streets, plans and behaviours. It’s like a hoe cutting through sagebrush, leaving a bitter aftertaste of irreversibility. In war, you become your true self, no need to play a role. You are simply a human, one of billions who ever lived on the Earth, sharing the commonality of breath. There’s no time for love at war. It lies abandoned next to a trash pile and disappears like a grandfather in a fog, lost somewhere behind this summer’s unharvested sunflower fields of a heart,” Kryvtsov said in a 2023 interview with Ukrainian publishing and literary organisation Chytomo as part of its Words and Bullets project with PEN Ukraine. Even through the chaos of war, Kryvtsov continued to write poetry. Many of his poems reflect on the harsh reality of war and the contrast between war and ordinary, civilian life. His first poetry collection Вірші з бійниці (Poems from the Embrasure) was hailed by PEN Ukraine as one of the best books of 2023. Within days of his death, the book’s entire print run had sold out and the reprint had racked up thousands of preorders. Profits from the book will be split between Kryvtsov’s family and projects to bring books to the armed forces. Hundreds of people gathered at St Michael’s monastery in Kyiv to attend a ceremony to honour Kryvtsov, ahead of a funeral in his hometown of Rivne. Some carried copies of his book, others a bouquet of violets, a reference to Kryvtsov’s final poem, posted on Facebook the day before he died (see below). The second part of the memorial service was held in Kyiv’s central Independence Square, the scene of the Euromaidan revolution in which Kryvtsov had participated. Mourners took turns stepping up to a microphone to share their memories of Kryvtsov and his poetry. He “left behind a colossal height of poetry,” said Olena Herasymiuk, a poet, volunteer and combat medic, who was a close friend of Kryvtsov. “He left us not just his poems and testimonies of the era but his most powerful weapon, unique and innate. It’s the kind of weapon that hits not a territory or an enemy but strikes at the human mind and soul.” (quote from the Associated Press) In an outpouring of grief on social media following Kryvtsov’s death, many drew parallels with Ukrainian cultural figures killed during the Soviet Union’s repression of writers and artists in the 1920s and 30s. Among these is the mighty figure of Isaac Babel, whose most famous collection of short stories Red Cavalry was written a century ago, inspired by Babel’s experiences as a war reporter in the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. I have recently been rereading the Red Cavalry stories and had intended my latest article to be about the historical parallels between Babel’s commentaries on war and contemporary war writers in Ukraine. That will have to wait for next time. Instead, I leave you with the prophetic poem Maksym Kryvtsov wrote the day before he died, and an extract from his poem about his ginger cat, posted on Instagram a few days earlier. My head rolls from tree to tree like tumbleweed or a ball from my severed arms violets will sprout in the spring my legs will be torn apart by dogs and cats my blood will paint the world a new red a Pantone human blood red my bones will sink into the earth and form a carcass my shattered gun will rust my poor mate my things and fatigues will find new owners I wish it were spring to finally bloom as a violet My Ginger Tabby When he falls asleep slowly stretches his front legs he dreams of summer dreams of an unscathed brick house dreams of chickens running around the yard dreams of children who treat him to meat pies my helmet slips out of my hands falls on the mud the cat wakes up squints his eyes looks around carefully: yes, they’re his people: and falls asleep again. Taken from Wikipedia, translation credited to Christine Chraibi  The foundations of the Russian invasion of Ukraine were laid eight years ago, during the Revolution of Dignity of 2013-14. Who can forget the images of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians standing in Kiev’s central square, the Maidan, through that bleak, cold winter, and their nightly stand-offs with black-clad riot police firing tear gas and stun grenades? The events of Euromaidan, as it is better known in the West, began when students demonstrated against then-president Viktor Yanukovych’s decision – under heavy pressure from Vladimir Putin – to abandon an agreement with the European Union in favour of closer ties with Russia. But on that occasion, Putin’s strong-arm tactics failed. Yanukovych was forced to flee, Ukrainians elected a pro-European government and the EU agreement was eventually signed. Faced with a choice between Europe and Russia, Ukraine overwhelmingly chose Europe. Putin’s obsession with winning back Ukraine began as soon as Euromaidan ended. He immediately began preparations to take Crimea and supply guns and heavy weaponry to eastern Ukraine to whip up insurgency in the traditionally pro-Russian former industrial heartlands of the Donbas region. The conflict led to the downing of a Malaysia Airlines flight in July 2014 by pro-Russian separatist fighters, killing all 298 people on board. The war has continued to rumble on inconclusively ever since, with sporadic outbreaks of violence. Over a million residents of eastern Ukraine were forced to leave their homes, many resettling in Kiev, now itself under fire. Putin always denied Russian military involvement in Crimea and the Donbas. Just as he denied Russian state involvement in the assassinations and attempted poisonings of his critics. And just as he denied, until a few short days ago, that he was planning military intervention in Ukraine. We long ago learned not to trust Putin, and we know from experience that his actions are unpredictable. One thing now seems clear: that Putin’s immediate intention is regime change in Ukraine – to install a puppet regime loyal to Russia in a country that he considers has no right to statehood. His justifications for doing so make little sense to most in the West. But since 2014 he has woven a narrative for domestic consumption in Russia in an attempt to rationalise intervention. Putin always couched Euromaidan in terms of a far-right coup by Ukrainian nationalists. Is this a true reflection of events? Absolutely not. But there is a tiny kernel of truth to it that Putin can exploit to his own ends. Although Euromaidan began as a pro-European student demonstration and attracted Ukrainians of all strata of society, right-wing nationalist parties did play a role in the fighting and the post-Maidan government did follow a policy of glorifying past nationalist leaders, many of whom collaborated with the Nazis. Hence, as Putin’s narrative goes, Ukraine is a country led by far-right extremists in need of ‘denazification’. His focus on Nazi ideology is supremely ironic, given that Ukraine until recently was the only country other than Israel to have both a Jewish president and prime minister. Another of Putin’s claims, that Ukraine is perpetrating genocide against its own citizens by targeting Russian speakers, is utter nonsense. Ukraine has always been a bilingual country, with Ukrainian widely spoken in the west and Russian elsewhere. But use of Ukrainian has become more prevalent since 2014 amid a heightened sense of national identity. A series of laws in recent years has designated Ukrainian the country’s official language and attempted to cement its use in most aspects of public life, including education and the media. The language laws provide grist to Putin’s rumour mill, information to manipulate into claims of genocide. Putin’s ultimate aims are not clear. We don’t yet know if he is planning for a permanent Russian occupation of Ukraine. Nor is Russian success a foregone conclusion. Ukrainians have become used to war in the last eight years and civilians are willing to fight to the death, as they did during Euromaidan. Many are wondering whether Putin will stop at Ukraine or push on with incursions into the Baltic States of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. My own sense is that the latter is unlikely, and if the war in Ukraine drags on inconclusively for months or years, impossible. Ukraine has been Russia’s bugbear since the events of 2014, and besides, an invasion of the Baltics – EU member states – would unleash a war with Nato on an unimaginable scale. The West’s attempts to persuade Putin against war have been derisory. Putin has no fear of sanctions, especially of the magnitude agreed so far. The West’s most powerful weapon against Russia is energy sanctions, such as those imposed on Iran: oil and gas exports provide more than a third of Russia’s national budget. But the US, EU and UK are unwilling to take measures that will harm their own economies and their own consumers, hence US restrictions on currency clearing will include carve-outs for energy payments. Around 70% of Russian gas exports and half its oil exports go to Europe. So far, Germany’s decision to halt the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia is the most significant of the measures taken by the West, but this is as far as Europe has been willing to go. The UK government is reluctant to force BP to abandon its 20% stake in Russian oil giant Rosneft, which is run by Putin ally Igor Sechin. BP's chief executive Bernard Looney sits on the Rosneft board alongside Sechin, a position that would surely be untenable if the UK took this war seriously. Amid insufficient coercion from the West, pressure to stop the war must come from inside Russia. Kremlin watchers are clear that this is Putin’s war, not Russia’s war. Protestors have come out onto the streets in many Russian cities – a rare and dangerous move under Putin’s authoritarian regime – evidence that the war does not have broad support among the Russian people. The defection of Russian soldiers combined with dissent among Putin’s inner circle could be the best hope of stifling the war in Ukraine and minimising bloodshed.  So the thing that most of us thought was unthinkable is now a reality. Russian tanks are entering Kiev, missiles are falling on cities across Ukraine, and the government is handing out weapons and giving instructions for making petrol bombs to its citizens in an attempt to defend the country from Russian domination. For those few Ukrainians with memories long enough to recall the last time foreign tanks rolled into Kiev, the Russian invasion must bring back terrible memories of the summer of 1941 after Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa. The German invasion of the Soviet Union brought to an abrupt end the non-aggression pact between the two great twentieth century dictators Hitler and Stalin. Tens of thousands of people fled Kiev, heading east to safety in the Urals or Central Asia. Today’s refugees from Kiev and other cities are fleeing to the west in an attempt to escape a war inflicted by the twenty-first century’s great dictator, Vladimir Putin. The Russian president has more than a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him. Like Stalin, he views the outside world as a hostile and threatening place and brooks no dissent. Stalin subjected his opponents to show trials, found them guilty on trumped-up charges and had them shot. Putin’s methods are more varied – poison for Alexander Litvinenko, Alexei Navalny and Sergei Skripal. Boris Nemtsov was shot while walking across a bridge, Mikhail Khodorkovsky imprisoned for a decade. Those are not the only similarities between the two dictators. Putin appears to be emulating Stalin in building a personality cult around himself, using propaganda and mass media to create a patriotic image of a heroic leader for the nation to glorify. Stalin, more than any other Soviet leader, was responsible for transforming the Soviet Union from a peasant backwater into a superpower to rival the United States. Today Putin calls the collapse of the Soviet Union the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century. If the worst-case scenario is realised, his invasion of Ukraine could represent the first step in an attempt to recreate the Soviet empire. It hardly comes as a surprise, then, that Putin is rehabilitating Stalin’s record after decades of condemnation. What Putin fears most of all is freedom: a free press, freedom of speech and expression, freedom to choose one’s own leaders or overthrow unpopular leaders. Freedom in Russia could bring about the end of Putin. And freedom in Ukraine has prompted the Ukrainian people to reject Russia in favour of the West. Ukrainians care passionately about their freedom, for it was hard won – in not one, not two, but in three revolutions, all centred on Independence Square in central Kiev, better known as the Maidan. The Revolution on Granite in 1990 was a student demonstration and hunger strike in open defiance of the Soviet establishment, part of a wave of dissent that helped bring about the end of the Soviet Union and Ukraine’s emergence as an independent country the following year. One of the students’ demands was the scrapping of a proposed union treaty with Moscow. The Orange Revolution of 2004 brought hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians back to the Maidan to protest about a presidential election claimed by the pro-Russian candidate Viktor Yanukovych that was marred by corruption, fraud and voter intimidation. The events of that winter are best remembered for the grey, pockmarked face of his poisoned opponent, Viktor Yushchenko, who eventually prevailed when the protestors’ demands were met and the election was re-run. Yushchenko believes the assassination attempt was ordered by Moscow when he attempted to steer Ukraine to closer integration with Europe. But the roots of this week’s Russian invasion can be found in Ukraine’s third Maidan revolution, the Revolution of Dignity in 2013-14, better known in the West as Euromaidan. Tempted with carrots and goaded with sticks from Putin, President Yanukovych (yes, the same one, back in power since 2010) turned his back on a long-awaited agreement with the European Union in favour of closer ties with Russia. What started as a peaceful student demonstration ended, three months later, as war. Protestors in motorcycle helmets carrying makeshift shields fought in the streets, using Molotov cocktails and fireworks against riot police armed with water cannon, tear gas, stun grenades and metal truncheons. In the final days of the conflict, the firearms changed to rifles and semi-automatic weapons, taking the lives of more than a hundred protestors. In the end, the Maidan won and Yanukovych fled, making him one of the few world leaders to be overthrown twice. But Ukraine paid a terrible price for the victory, not only in the lives lost during the conflict, but in the revenge taken by Putin for the country’s pivot away from Russia and towards the West. Within days of Yanukovych’s departure, the Russian president began preparations to annex Crimea. Weeks later, he was stirring up pro-Russian sentiment and providing arms to separatists in the Donbas, fomenting a war that never ended and has killed around 14,000 people, some 3,000 of them civilians. Part two of this article, on Putin’s goals and the West’s response, will be published on my website tomorrow.  So, Ukraine may soon be at war once again. Over 100,000 Russian troops are massing at the Ukrainian border, including in Belarus – just a few miles from the Ukrainian capital, Kiev. The Americans are piling weapons into the country and pulling out their diplomats, Nato is reinforcing its eastern borders, and Israel is preparing for another mass wave of immigration by Ukrainian Jews. Linked to Russia by centuries of history, and an economic powerhouse of the Soviet Union thanks to its agriculture, coal and heavy industry, Ukraine has changed enormously since gaining independence in 1991. When I first visited, in January 1992, Kiev was a drab, grey Soviet city, its beauty masked by leaden skies and decades of stagnation. The streets were covered in snow – lovely in the early morning after an overnight flurry, but later slushy and treacherous with ice. There were few opportunities to escape the cold – pleasant ones at least. My friend and I ducked into a restaurant for some respite; it served nothing but cucumbers and garlic, both pickled, and unidentifiable meat and gristle patties, or kotleti. Being vegetarian in the embers of the Soviet Union wasn’t easy. The waitress brought us a sorry-looking bunch of red carnations and indicated two men at the only other occupied table, who wanted to give them to us. We declined. They started shouting. It all got a bit nasty and we left as quickly as we could. That was not an unusual experience at the time. Today Kiev is a thriving city with a young, highly educated population, tech savvy industries and a wealth of eateries serving cuisines from all over the world. It looks to the west, rather than the east, after the hard-won popular uprising of 2013-14 – the Revolution of Dignity – which deposed the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. That brutal three-month stand-off brought tens of thousands of protestors to Kiev’s central Independence Square, or Maidan, in sub-zero temperatures. It began as a demonstration against the president’s refusal to sign an agreement with the European Union to enable greater rapprochement, and ended in all-out war against a government rife with corruption and cronyism that used horrifying violence against peaceful protestors. More than 100 people died during the conflict. I am currently immersed in the events of that winter, which form the backdrop to part of my half-finished novel. Russia took its revenge for Ukraine’s reorientation to the west with the annexation of Crimea and by fostering war in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine, which has killed around 14,000 people, some 3,000 of them civilians caught in the crossfire. Over a million residents of eastern Ukraine have been forced to leave their homes. The conflict led to the downing of a Malaysia Airlines flight in July 2014 by pro-Russian separatist fighters, killing all 298 people on board. The war has continued to rumble on inconclusively ever since, with sporadic outbreaks of violence. Russian president Vladimir Putin has always denied Russian military involvement in Crimea and the Donbas. Ukrainians referred to the armed troops piling into Crimea in February-March 2014 as “little green men”. Putin insisted the little green men were local self-defence groups – who just happened to be wearing Russian army uniforms – and had nothing to do with him. In the warring Donbas, he put responsibility firmly at the feet of pro-Russian separatists in Ukraine and insisted any Russian nationals in the rebel-held region were there on a purely voluntary basis. Western countries have always accused Russia of providing troops, equipment and funding to the separatists and have sanctioned Moscow over its role in the conflict. Indeed, the presence of Russian troops was proven during a recent unrelated court case. Fast-forward to today and Putin is making no denials about the troops massed on Ukraine’s borders. The increasing militarisation is bringing the possibility of war in Europe ever closer. But the Russian leader has always been unpredictable and his intentions are very difficult to second guess. Destabilising an increasingly western-oriented democracy on his doorstep – in a country he considers within Russia’s sphere of influence – has long been his intention. If Ukraine is allowed to thrive, his worst nightmare could come true – Nato and the European Union wielding influence right on his doorstep. What form this war may take is anyone’s guess. Hybrid warfare is already well underway with a cyber-attack on Ukrainian government websites earlier this month and warnings of a “false flag” operation by Russian saboteurs in the country to create a pretext for an attack. There is talk of a Russian puppet-leader – former Ukrainian MP Yevhen Murayev – waiting in the wings to replace President Volodymyr Zelensky. Another politician named in the alleged plot is Mykola Azarov, formerly Ukraine’s prime minister under Yanukovych. Ukraine and the West will have to wait and see what Putin decides to do next. We may not have to wait very long.  Five years ago this month Ukraine's Maidan protests were at their height, a precursor to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March of that year. The night of 22 January 2014 marked a turning point in events at the Maidan square in central Kiev, the night when the first killings took place. The demonstrations had begun in late November as a protest against President Viktor Yanukovych’s eleventh-hour refusal to sign an Association Agreement with the European Union, a deal that would have consolidated ties with Europe, but was far from a precursor to joining the EU club. Through the cold, bleak Ukrainian winter, crowds gathered every evening in the large central square that became known as the Euromaidan. Many remained permanently on site, sleeping in tents and warmed by bonfires, living off donated food heated on makeshift stoves. The original protestors, made up largely of students and young professionals, had been joined by their parents’ generation, angry at the authorities’ aggressive treatment of the young demonstrators, a core of passionate pro-Europeans from parts of Western Ukraine that had previously been part of Poland or Austria, as well as a well publicised and aggressive bunch of die-hard members of radical right-wing movements. Encouraged by Russian President Vladimir Putin, Yanukovych had forced a raft of repressive measures through parliament. The ‘dictatorship law’ passed on 16 January made the erection of tents without police permission illegal as well as the wearing of hard hats during public demonstrations, among other measures. Shortly afterwards riot police used water cannon in an attempt to break up the crowds, then rubber bullets, stun grenades and tear gas. For their part, the protestors retaliated with cobbles, fireworks and home-made petrol bombs. They built up barricades into huge bulwarks surrounded with burning tyres. The peaceful protests had become a Revolution. On 22 January, the body of Yuriy Verbytsky – a middle-aged seismologist-turned-activist from Lviv in Western Ukraine – was found in the forest near Kiev’s Boryspil airport, his ribs broken and remnants of duct tape over his hands and clothing. He had been abducted the previous day with his friend Igor Lutsenko, an opposition journalist. Lutsenko claims the men were thrown into a van, taken to the forest and locked up separately in an abandoned building. He was beaten, interrogated, forced to his knees with a bag over his head and told to pray, in what he described as a mock execution. Lutsenko, who was far from the only journalist to suffer brutal injuries at the hands of riot police while covering the Euromaidan protests, made it out alive. Verbytsky was left to freeze to death. The same night, police killed three protestors during riots on Hrushevsky Street, close to Kiev’s national gallery. Two were attacked and shot. A third was beaten, stripped, jabbed with a knife and made to stand naked in the snow singing the national anthem. Altogether 130 people would die during the Euromaidan demonstrations, the vast majority civilian protestors. Eighteen police officers were also killed during the clashes. I will write some of their story next month to mark the anniversary of the killings of 20 February, which brought an end to the Revolution as Yanukovych fled to Russia and Putin began his annexation of Crimea.  Following on from my previous post, I have been reading lately about Ukraine’s 2014 Euromaidan Revolution. One book I have re-read is Andrey Kurkov’s Ukraine Diaries: Dispatches from Kiev, a fascinating first-hand account of the events, written by a local writer living close to the Maidan, Kiev’s Independence Square, which is at the heart of the action. From his apartment, Kurkov can smell the burning barricades and hear the sounds of grenades and gunshot. The diary portrays the horrific violence perpetrated against many innocent victims, the powerful sentiments of injustice felt by the protestors and the fears generated by an ever-changing political climate, interspersed with the mundane day-to-day trials and tribulations of family life. It also sheds light on Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March of that year and on the ongoing conflict in the Donbas of eastern Ukraine, the heartland of then-president Viktor Yanukovych. This week in 2014 marked the climax of events in Kiev. On 18 February, violence broke out during a peaceful march on parliament in which protestors demanded a change to the constitution to limit the powers of the president. “And then, about two o’clock, the situation suddenly worsened. Activists invaded the Party of Regions headquarters and set fire to it. The Berkut [riot police] threw grenades and fired rubber bullets, from the ground and from the rooftops,” Kurkov writes in his diary entry for that day. Still on 18 February, he mulls: “What will happen next? The dissolution of parliament, the announcement of new elections in six months, the lifting of parliamentary immunity for opposition deputies and their arrests? This country has never had such a stupid president before, capable of radicalising one of the most tolerant populations in the world!” The following day, 19 February, he writes “In Kiev, they are counting the dead, the wounded and the disappeared…The hospitals are overflowing right now. But many of the wounded are in hiding, from their friends as well as from strangers. They are afraid of going to hospital because the police have often abducted injured protesters from there to take them to the station, without offering them any medical care.” And here is an insight into the sharp divide between the European-oriented western Ukraine that Kurkov inhabits and the Russian-dominated east of the country exemplified by the industrial city of Donetsk: “Hatred is overflowing. It is born from a simple dislike of a Donetskian government that is both strange and foreign; a dislike that, by perhaps growing too fast, has become hatred, and is currently raging through western Ukraine, in Odessa, Cherkasy and other places. Meanwhile Crimea is once again calling on Russia to take it back.” The following day, 20 February, Kurkov writes: “Today a lecturer from the Catholic University in Lviv was killed, along with several dozen other people. Snipers are shooting even at young nurses…There are rumours everywhere, each one more disturbing than the last, but the reality in this country is already horrifying: today, in St Michael’s Square, two policemen were killed. Why? Who needs that? It is obviously the hand of Moscow, pushing us into a state of war…”. And on the 21st: “In Kharkiv, the regional governor is assembling a congress of deputies from the south and east of Ukraine to study the possibility of separating from Kiev. The country is trembling all over – it is close to being torn apart – but Yanukovych doesn’t see this.” On 22 February Yanukovych fled, having earlier that day signed an agreement with the opposition to make the constitutional changes demanded by the opposition and setting out plans for a presidential election by the end of the year. The diaries continue through to late April, by which time Russia had annexed Crimea following a hastily arranged referendum in March and the conflict in the east of the country was beginning. Russians were infiltrating eastern Ukraine to organise pro-Russian rallies, their troops and military apparel massing at the border, all of which President Putin denied, and armed separatists were occupying government buildings. “What frightens me is a possible Russian intervention in the east and south of the country. It would be wonderful not to have to think about the possibility of a war, but a day has not passed without that possibility crossing my mind,” Kurkov writes on 24 March. That war has gone on to take the lives of more than 10,000 people. More than 2 million have been made homeless. Ukraine Diaries: Dispatches from Kiev by Andrey Kurkov is published by Harvill Secker, London, 2014.  This month marks the fourth anniversary of Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, which led to the ousting of President Viktor Yanukovych, and later, the Russian annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbass. The seeds of the revolution were sown when the president failed to sign an association agreement with the EU in November 2013, having initially agreed to do so. People took to the streets in protest, setting up a base camp in the Maidan, Kiev’s central Independence Square. After weeks of mostly peaceful demonstrations, a march on parliament on 18 February turned violent. Police fired rubber bullets and used tear gas and grenades. The protestors fought back with makeshift weapons. Two days later, police began firing live ammunition, including automatic weapons and sniper rifles. Some 80 people were killed. Despite concessions from President Yanukovych, the protests continued and the demonstrators took control of much of Kiev. The president fled and new elections were called. The Euromaidan Revolution is remembered as a conflict between pro-Europeans (mostly in Kiev, the west and centre of the country) and pro-Russians predominantly from Ukraine’s east. I have been reading about the history of Ukraine, which – apart from a brief stint in 1918 during the Russian Civil War – had never existed as an independent country until 1991, to make sense of recent events. The country’s very name, Ukraina, means border, or edge. This region of flat, fertile steppe land was always on the edge: the edge of Europe, the edge of empires, the edge of Russia. A large swathe of western Ukraine belonged to Poland for much of its history; some formed part of Lithuania, while other areas were in the Hapsburg or Ottoman Empires. Much of the territory became part of the Russian Empire. The western fringes were a true borderland, endlessly invaded and conquered, the frontier between nations ever shifting. Ukraine as we know it today is a very recent concept. The capital Kiev developed owing to its position on a trade route between the Baltic and the Black Seas along the River Dnieper, and became a sophisticated trading centre in medieval times, with links to Constantinople. It is known to historians as Kievan Rus. Both Ukrainians and Russians believe their ancestry derives from Kievan Rus, Russians claiming that their descendants moved away from the Dnieper region to found Muscovy, several hundred miles to the northeast, bringing the culture of Kievan Rus with them. This helps to explain why Russians feel such a strong connection to Ukraine, and why any move by Ukraine’s leadership towards rapprochement with Europe at the expense of Russia provokes hostile feelings. Ukraine’s position as ‘Little Russia’ dates from a deal between Cossack leader Khmelnytsky and the Russian Tsar in 1686. The Little Russia narrative was promoted under Catherine the Great a century later, when Russia experienced waves of expansion and large swathes of present-day Ukraine – including the areas with a large Jewish population that became the Pale of Settlement – joined the Russian Empire as a result of the partitioning of Poland. Further east and south was a Cossack stronghold, while the east was largely unpopulated steppe until coal-mining began in the late nineteenth century. Russian peasants were attracted to eastern Ukraine during its industrial revolution and again during Stalin’s industrialisation drive, populating the growing towns and cities. Today the majority of population of this region, the Donbass, still aligns itself with its Russian Motherland. As for Crimea, while the annexation of territory by another country is clearly deplorable, Crimea’s historical links to Ukraine are tenuous. Although parts of Crimea entered into the territory of Kievan Rus, the area was for much of its history a Tatar land ruled by the Ottoman Empire. Crimea was won by Catherine the Great in 1783, becoming part of the Russian Empire and later the Russian Soviet Socialist Republic. It was not transferred to the Ukrainian SSR until 1954. Its population at the beginning of the twentieth century was a mixture of Crimean Tatars as well as Russian newcomers, Ukrainians, Germans, Greeks, Jews and others, mainly attracted to the region by its fertile land. So Ukraine was never a homogenous entity. Its depiction as Little Russia may have accurately characterised parts of the future nation, but this was largely an artificial notion, a process of Russification imposed from above by both the tsars and the Communists that resonates more with Russians than Ukrainians. Likewise the rise of Ukrainian nationalism at the beginning of the twentieth century, which is celebrated by a large and vocal right-wing nationalist movement today, also was representative of only a small section of society. For an excellent insight into the Ukrainian Revolution of 2014, I recommend Ukraine Diaries by Andrey Kurkov. Anna Reid’s Borderland provides a highly readable and entertaining discourse on Ukraine’s history.  In my third and final blog post on Jewish life in Ukraine past and present, based an article that appeared recently in the Jerusalem Post, the focus turns to Ukraine’s current wave of nationalism and its impact on the Jewish community. The presence and place of Jews in the still-crystallising Ukrainian state remains a sensitive issue, but this is not primarily because of a physical threat to Jewish well-being. Jewish communal buildings in Kiev require considerably less physical security around them than do their equivalents in Western Europe. Nationalist groups, nevertheless, played a very visible role during the Maidan protests. The author witnessed the proliferation of banners of the far-right Svoboda Party on the square in December 2013 alongside the red and black flags invoking the memory of Stepan Bandera’s UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army). The armed volunteer groups, which bore the brunt of the fighting in the summer of 2014 when the Ukrainian army faltered, flew similar colours. But the nationalist candidate in the presidential elections of 2014, one Dmitro Yaros, scored just 0.7% of the vote. Svoboda also achieved a tiny showing in presidential elections. Efforts by the volunteer battalions to transform themselves into political parties have as yet achieved meagre results. “Ukrainians don’t want to be led by extremists,” a young man in Kiev told me. Still, while nationalist political achievements remain marginal and levels of antisemitic violence low, the debate over national memory and its symbols continues to raise difficult questions for Ukraine’s Jews. Eduard Dolinsky, executive director of the Kiev-based Ukrainian Jewish Committee says the apparent electoral weakness of the nationalists is deceptive. Dolinsky pointed to their strength at the municipal level. He is concerned at the role of what he called “apologists of national memory” – propagandist pseudo-historians who seek to downplay the role of Ukrainian nationalist movements in the Holocaust and the persecution of Jews in Ukraine. Dolinsky says of such figures as Bandera and Roman Shukhevych: “They participated in the Holocaust. Then people present them as protectors of Jews. This is Holocaust denial and desecration of Jewish memory.” The placing of these figures in a mainstream pantheon of national heroes in Ukraine is evident. In July 2016, a major street in Kiev was named for Bandera. On May 25, 2016, the Ukrainian parliament held a minute of silence for Petlyura. Other voices, both Jewish and non-Jewish, dispute the gravity and implications of the “mainstreaming” of wartime nationalist leaders. Josef Zissels, chairman of the Vaad organisation of Ukrainian Jews, was quoted recently warning against “unnecessary assignment of blame” in a country where Jews enjoy formal equal rights and levels of antisemitic violence are low. The country faces enormous challenges ahead in the building of institutions, fighting systemic corruption and forging a version of national identity with which all elements of society can at least broadly identify. The Jews, both the actual living examples of them in Ukraine and no doubt also the mythical, archetypal Jew that never seems to quite vanish from the European consciousness, will be playing a role in this. For the full article, see/http://www.jpost.com/Jerusalem-Report/In-the-land-of-the-trident-503106 w ww.jpost.com/Jerusalem-Report/In-the-land-of-the-trident-503106  My blog has taken a back seat in recent weeks over the children's long summer holiday. Catching up on the newspapers once they returned to school this week, I came across this article on Jewish life in Ukraine that recently appeared in the Jerusalem Post. Much of it based on interviews the author conducted recently in Kiev and elsewhere with Jews displaced by the war in the east of the country. I found this piece fascinating and worth reproducing almost in full. As it’s very long, I will post in instalments. Here is the first of three: Ukraine is a territory saturated in Jewish memory – memory both tragic and sublime. In every field of endeavour – religious thought, Zionist and socialist politics, art, music, military affairs, science – Jews have excelled. It is the birthplace of Rabbi Yisrael ben-Eliezer, the Baal Shem Tov, founder of Hasidic Judaism, who grew up near Kameniec in what is now western Ukraine; Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement, who was born in Miedzyboz in central Ukraine; Haim Nachman Bialik, the poet laureate of modern Hebrew literature, who was born in Zhitomir, in north central Ukraine. Goldie Meyerson, who became prime minister Golda Meir, was born in Kiev. Israeli-born Moshe Dayan, famed fighter and commander, was the son of Shmuel Dayan, who came from Zhashkiv, in the Cherkassy region, central Ukraine. Isaac Babel, one of the foremost Soviet novelists of the mid-20th century, whose “Red Cavalry Tales” remains a classic of 20th-century Russian literature, came from Odessa. Leon Trotsky, born Lev Bronstein, architect of the Russian revolution and founder of the Red Army, came from Yanovka, in the Kherson region of Ukraine. Vladimir Ze’ev Jabotinsky, father of Revisionist Zionism, came from Odessa. Solomon Rabinovitch, better known as Sholem Aleichem, came from Pereyaslav, in the Kiev governorate. And so on. The area has played host to an astonishing gathering of Jewish creative energies. It is also prominent among the lands of destruction. Ukraine is the land of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, whose statue on his horse and brandishing his famous rhino horn mace stands outside St Sophia’s Cathedral in central Kiev; his Cossack rebels butchered 100,000 Jews in a 17th-century uprising. It is the land of Simon Petlyura, whose fighters followed a similar murderous path during the chaotic period following the Russian revolution of 1917. And, of course, it is the land of the “Holocaust of bullets” of the mobile killing squads who followed the German armies as they swept through Ukraine in the summer and autumn of 1941, systematically slaughtering Jewish populations in the verdant ravines and forests that characterize the country’s landscape until 1.5 million were dead. [Photo - Simon Petlyura] So, Ukraine is filled with Jewish ghosts, its soil with Jewish blood. But there is Jewish life here, too. Estimates of the precise Jewish population vary widely. The European Jewish Congress claims that 360,000- 400,000 Jews live in Ukraine, which would make it the fifth largest Jewish community in the world. Other estimates place the number as low as 60,000. Since 2014, Ukraine has been embroiled in renewed strife and conflict. War returns to Ukraine In summer, Kiev is a charming city filled with cafes and light. But the peaceful atmosphere is deceptive. History has not departed. Ukraine has been shaken in recent years once again by revolution, and its handmaiden, war. The Euromaidan Revolution toppled the pro-Russian government of President Victor Yanukovych in March 2014. Yanukovych’s departure was followed by the Russian seizure of Crimea and then the outbreak of a Russian-supported separatist insurgency in the Donbass – the eastern provinces of Donetsk and Luhansk. The ill-equipped, rusty Ukrainian forces moved to crush the insurgency but were met by the entry of conventional Russian troops in August. The Ukrainians suffered bloody setbacks in the battles of Ilovaisk and Debaltseve, before a cease-fire agreement was signed in Minsk on February 11 2015. The war is not over, and the issues that led to its outbreak have not been resolved. Today, the Ukrainians and their Russian enemies face one another along a static 400km frontline. Observers from the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe monitor the ceasefire. This reporter spent several days in the war zone of eastern Ukraine; shooting across the lines is a nightly occurrence. And not just rifles – RPG, self-propelled grenades and machine guns too. Over the past three years, 10,090 people have died in this largely forgotten conflict. More than 2 million people have been made homeless. The war has impacted on Ukraine’s Jewish community in two central ways. Firstly, Jews resident in eastern Ukraine have suffered the direct physical effects of the fighting. Most of Donetsk and Luhansk’s Jews fled westward as the frontlines approached their homes in 2014. The provisions offered by the Ukrainian authorities to those made homeless by the war are minimal. Efforts are ongoing by a variety of Jewish organisations to provide for Ukrainian Jews who have become refugees. The second impact is a little less tangible. The war of 2014 was an important moment in the ongoing development of national identity in independent Ukraine. This is a complex and sometimes fraught business, and Ukraine’s Jews are part of it whether they like it or not. Ukraine remains divided between pro-Western and pro-Russian forces. Both of these broad camps contain fringe elements that are hostile to Jews. On the pro-Russian side, neo-Nazi groups such as Russian National Unity and a number of Cossack groups maintain an armed presence in separatist controlled parts of Luhansk and Donetsk. On the Ukrainian side, there are also militia groups active in the combat zone that use far right and neo-Nazi imagery. But more importantly, the mainstream Ukrainian leadership is keen to make use of a nationalist heritage that celebrates Khmelnytsky and Petlyura, and which includes organisations and figures that collaborated with the Nazi invaders during World War II, and with the persecution and murder of Ukraine’s Jews at that time. The public commemoration of such wartime nationalist leaders as Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych remains a starkly divisive issue that is unlikely to lessen in intensity over time. To read the original article in full, click here http://www.jpost.com/Jerusalem-Report/In-the-land-of-the-trident-503106 |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed