|

The images circulating in recent days of joyful Ukrainians celebrating the Russian retreat from Kherson tell a rare story of hope amid the devastation of war. Kherson was captured in early March, just days into the Russian invasion, and since then had remained the only Ukrainian regional capital under Russian occupation. For Moscow, the Kherson region provided a foothold west of the Dnieper river, a tactical location to facilitate a Russian push further west – to Odesa, seen as one of the most valuable prizes for Russian president Vladimir Putin. As well as being a key strategic port on the Black Sea, Odesa was known as the jewel in the crown of the Russian Empire, so called for its glorious situation, architecture and cultural heritage. Just a few short weeks ago, Putin announced with great fanfare that Russia had annexed the whole of the Kherson region – together with the regions of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia – and that it would remain Russian forever. Moscow still claims this to be the case, but its words now ring hollower than ever. The liberation of Kherson feels like a watershed moment in the conflict, and it is little surprise that some have made historical comparisons with Stalingrad – the most crucial turning point of World War II. This brutal battle was fought from August 1942-February 1943 and finally resulted in a Soviet victory, triggering the German retreat from the Soviet Union. “After Kherson, it will be the turn of Donetsk, Luhansk and Zaporizhzhia, then Crimea. Or Crimea could be first, followed by Donbas, depending on how the situation plays out on the battlefield,” Roman Rukomeda, a Ukrainian political analyst, optimistically predicts. Whether the Russian retreat from Kherson indeed turns out to be a pivotal event in the Ukraine war remains to be seen. Kyiv remains wary of a Russian trap or ambush and consolidation of Russian positions east of the Dnieper raise fears of another bombing campaign. The recent heart-breaking BBC documentary Mariupol: The People’s Story offers a terrible reminder of the utter devastation that city and its population suffered under Russian bombardment earlier this year… …Which brings me to another World War II comparison from the same part of the world. SHTTL is a new film showing at the UK Jewish Film Festival this week, set in a Ukrainian shtetl near Ternopil close to the Polish border on the eve of the Nazi invasion in June 1941. Like the scenes in the BBC documentary of Mariupol and its inhabitants before the Russian invasion, the film depicts a location and way of life that is on the verge of vanishing completely. Its title, SHTTL, purposefully drops the letter ‘e’ to symbolise the disappearance of Jewish shtetl life and acts as a tribute to those who lived there. The action centres on Mendele, a young man returning to the shtetl to get married having left for Kyiv to pursue a career as a filmmaker. It follows his interactions with friends, family members and neighbours; their debates, discussions and arguments. Only the viewer knows, of course, that the wedding will never take place; that the community is about to be destroyed, its residents shot and buried in shallow pits. This is a Holocaust film with a difference, for rather than depicting death and suffering, it depicts life, with its diverse mix of joy and sorrow and disappointment. Written and directed by Ady Walter, and with dialogue entirely in Yiddish, SHTTL was filmed in a purpose-built village 60 kilometres north of Kyiv. The set includes a reconstruction of the only remaining wooden synagogue in Europe, which was blessed and consecrated to enable it to hold real-life prayer services. Household items from the 1940s were sourced from all over Ukraine. The village was intended to be transformed into an open-air museum to educate local schoolchildren and help Ukrainians to better understand their Jewish history and culture. The area north of Kyiv, of course, was under Russian occupation in the early weeks of the current war. The utter devastation wreaked by the Russian troops and their complete disdain for human life, as witnessed in Bucha, Irpin and elsewhere, leaves the museum project up in the air. “We don’t know what’s happened to it now,” Walter told the The New European. “We know it became a minefield around there and that there was heavy fighting, but we have no idea what has become of the construction.” Mariupol: The People’s Story is on BBC iPlayer in the UK and will be available on other BBC platforms for viewers elsewhere. SHTTL will be screened in London at the UK Jewish Film Festival at 6pm on Thursday 17 November. It is not yet on general release. A tour of the film set is available on YouTube:

0 Comments

My final article of this year is also the last in a series I have written in recent months to honour the memories of those murdered at the ravine of Babi Yar on the outskirts of Kiev, Ukraine, 80 years ago. This time, I will end on a forward-looking note, discussing a new, thought-provoking piece of music theatre designed to move, challenge and inspire. In September 1941, the occupying Nazi forces and their Ukrainian collaborators murdered more than 33,000 Jews at Babi Yar over just two days, beginning on the eve of Yom Kippur. In the following two years of Nazi occupation, Babi Yar became the scene of over 100,000 deaths. This year a group of three Ukrainian musicians journeyed deep into their shared history, drawing on survivors' testimonies, traditional Yiddish and Ukrainian folk songs, poetry and storytelling to produce a new music theatre performance – Songs for Babyn Yar (to use the Ukrainian name for the killing site). The production weaves languages, harmonies and cultures to reveal the forgotten stories and silenced songs from one of the most devastating periods in Ukraine’s past and questions how we can move forward. Songs for Babyn Yar features haunting music from Svetlana Kundish, Yuriy Gurzhy and Mariana Sadovska, all originally from Ukraine but now based in Germany. They are ethnically Jewish and Russian Orthodox and between them perform in Ukrainian, Russian, English, German, Yiddish and Hebrew. Artistic director Josephine Burton, from the British cultural charity Dash Arts, has helped, in her words, “to tease out a narrative that will encompass this shared joy in each other, whilst not shrinking away from the darkness and the horrific tragedy at its heart”. In an interview with the London-based Jewish Chronicle in November, Kundish described the deeply personal link she feels to Babi Yar thanks to a 94-year-old survivor among the congregants of the synagogue in Braunschweig, Lower Saxony - where she serves as the first female cantor - and the close friendship they formed. When the Nazis occupied Soviet Ukraine in the summer of 1941, 13-year-old Rachil Blankman’s parents sent her away from Kiev to Siberia with a sick aunt, while they stayed behind to wait for Rachil’s missing brother to come home. The family that she left behind in Kiev were murdered at Babi Yar. The orphaned teenager eventually returned to Kiev and struggled through many years of hunger and of poverty, but eventually gained a university degree and became an engineer. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Rachil moved to Germany. “Her whole life story is a statement that despite everything, she found a way not only to survive, but also to live a happy life,” Kundish says. Rachil represents the “main voice” of Songs for Babyn Yar. “We have excerpts from the story of her life incorporated into the body of the show, so her voice comes in and out at certain moments, and the music is in a dialogue with her memories,” Kundish says. The willingness in Ukraine today to recognise the atrocities committed at Babi Yar, with major research projects and a new memorial centre underway (which I have written about here) contrasts sharply with the Soviet era, when Jewish memory and culture were all but erased. The Soviet poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko was banned from reading his 1961 poem Babi Yar (which was later used by the composer Dmitry Shostakovich in his 13th symphony) in Ukraine until the 1980s. And Lithuanian soprano Nechama Lifshitz was barred from performing in Kiev after she sang Shike Driz’ Yiddish Lullaby to Babi Yar at a concert in the city in 1959. Kundish hopes that Songs for Babyn Yar will reach out to as wide an audience as possible and will be part of an ongoing conversation. “I want [people] to tell their children or grandchildren about it. I want them to keep the memory alive because this is a hard chapter of history and it should not be forgotten. And people who live in Ukraine, especially the young generation, they should know about it…I want it to be broadcast on Ukrainian television. I want people to accidentally push the button and end up on this channel and just listen. That’s what I want.” Songs for Babyn Yar debuted at JW3 in London on 21 November 2021 and will be performed at Theatre on Podol in Kiev on 7 December. A short extract is available on YouTube.  Antony Blinken is on the cusp of being appointed Secretary of State in the new administration of President Joe Biden. One thing many people may not know about Blinken is that his great-grandfather was a Yiddish writer of some repute. Meir Blinken was born in 1879 in Pereyaslav, Ukraine – coincidentally the same shtetl as Yiddish literature’s most famous name, Sholem Aleichem. Blinken gained a Jewish education at a Talmud Torah, before attending the secular Kiev commercial college, part of a joint educational project founded by Ukrainian and Jewish businessmen. He worked as an apprentice cabinet-maker and carpenter, before switching to become a massage therapist. Indeed, he is listed in the Lexicon of Modern Yiddish Literature with the trade of masseur. His son Moritz, Tony Blinken’s grandfather, who became an American lawyer and businessman, was born in Kiev. Blinken Senior emigrated to the US in 1904. His first story, written under the pen-name B Mayer, was published a year earlier, in 1903. Once in America, his sketches and stories appeared in a range of literary, progressive socialist and labour Zionist publications, including the satirical magazine Der Kibetzer (Collection) and Idishe Arbeter Velt (Jewish Workers’ World) in Chicago. In all, he published around 50 works of fiction and non-fiction. Blinken’s books include Weiber (Women), described in the lexicon as a prose poem, Der Sod (The Secret) and Kortnshpil (Card Game). A collection of his short stories published in 1984 and translated by Max Rosenfeld, is still available. His writing dealt with thorny topics including the effects of poverty, poor living conditions, religious strictures, inadequate education and the lack of understanding that immigrants feel about their new country. Most controversially, he was one of the few male Yiddish writers to address the subject of women’s sexuality, writing about marital infidelity and sexual desire and hinting at the sense of boredom felt by housewives. Another subject he tackled remains controversial to this day: showing empathy towards abortion. Writing in a review of Blinken’s work in the 1980s, the journalist and author Richard Elman pointed out that among Yiddish authors writing for the largely female audience of Yiddish fiction, Blinken “was one of the few who chose to show with empathy the woman’s point of view in the act of love or sin”. Elman and others believed that the greatest legacy of the author’s work was that it vividly evoked the atmosphere and characters of the very early Jewish diaspora in New York. According to a 1965 article by the journalist David Shub in the Jewish newspaper The Forward, Blinken was the first Yiddish writer in America to write about sex. In the same article, he wrote that Blinken was also an editor’s nightmare! By the time of his death in 1915 at the age of just 37, Blinken had opened an independent massage office on East Broadway, in the heart of what was at that time the city’s Yiddish arts and letters district. While his writing was very popular among Yiddish-speaking Americans of his own generation, Blinken’s star quickly waned after his death. Photo credit: Ukrainian Jewish Encounter  I have written before about the revival of the Yiddish language and was interested to read about a Yiddish version of Fiddler on the Roof that has taken New York by storm. A Fidler afn Dakh, as it is called, opened last year at the Museum of Jewish Heritage before moving to a large, commercial theatre, Stage 42, in February. The Yiddish production comes more than half a century after the musical first opened on Broadway in 1964. It would become the longest-running musical in Broadway history, as well as a blockbuster film. It is the authenticity of the latest production that has wowed critics and audiences and makes the show so moving. Yiddish is, of course, the language that the fictional dairyman Tevye and his neighbours would have spoken. Fiddler is based on a series of short stories by Sholem Aleichem set in Anatevka, a fictional shtetl near Kiev in present day Ukraine. My family, too, came from a shtetl near Kiev and in fact my great-grandmother and great-great-grandmother once met the famous Yiddish writer during a holiday at a country dacha. In the course of this meeting, they discovered that they were related. The family name on both sides was Rabinovitch, although I have never actually managed to put my finger on the branch of our family tree that links me to Sholem Aleichem. Yiddish was once spoken by around 12 million people and transcended national boundaries. But the language was almost wiped out by the holocaust. Almost...but not quite. Jewish immigrants to America brought Yiddish with them and plays in Yiddish were common in New York in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There was even a Yiddish theatre district in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. But you might think that the potential audience for a Yiddish production of Fiddler today would be pretty limited. The show’s director, Joel Grey, told the Financial Times, “I thought it was kind of crazy, that six people would understand it”. Only six out of a cast of 29 spoke any Yiddish at the outset, three of them being native speakers. However, anyone already familiar with other stage or screen versions will be able to understand much of the production even without knowing Yiddish, and it has English and Russian surtitles to help the uninitiated. But for those who grew up surrounded by Yiddish, the production is likely to strike a particularly deep emotional chord. “For me, it’s not just the fusillade of familiar words and phrases: meshuga, geklempt, zay gezunt. It is the sound of my own grandparents and all that they lost in leaving their Anatevkas,” wrote Jesse Green in The New York Times. Yiddish was the language of the mundane, the every-day. It was the ‘mame-loshn’, or mother tongue, as opposed to ‘loshn-koydesh’, or holy tongue, meaning Hebrew. Grey calls it “the language of the outcast”. Much of the Jewish intelligentsia quickly abandoned the language on arrival in the West in order to assimilate. Yiddish represented the poverty and persecution of the world they had left behind. Also helping the authenticity of the piece is its simplicity. The big Broadway show style is stripped away in favour of a greater emphasis on the simple human choices and everyday trials and emotions of the struggle to preserve Jewish traditions in an era of ever greater assimilation and persecution. The production “though not without its comic moments, is suffused with a hauntingly melancholic aura that seems to foretell the annihilation of the world depicted on stage,” writes Max McGuinness in the FT. For more information, the production’s website can be found at http://fiddlernyc.com/#home. The Financial Times article about it is available here https://www.ft.com/content/f38136ee-cef6-11e9-b018-ca4456540ea6 And The New York Times review here https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/17/theater/review-yiddish-fiddler-on-the-roof.html Back in March 2018 I wrote a blog post about the origin of Jewish surnames in the Russian Empire. I recently came across as series of articles about surnames that covers other parts of the Jewish world too.

Across much of central eastern Europe, surnames became commonly used from the late 18th century with the first of a series of laws that required the population of the Austro-Hungarian empire to adopt hereditary names. One of several decrees issued by emperor Joseph II, who ruled from 1765-1790, stated that new hereditary names should be German, which helps to explain why so many eastern European Jews have German-sounding names. But not all Jews were subjects of the Austro-Hungarian empire, and not all those who were obeyed the decree. For example, those descended from the priestly groups Cohen and Levi often noted this status in their surname, helping to make these some of the most common Jewish names today. Before the late 18th century, the only Ashkenazi Jews that had adopted surnames were those belonging to certain rabbinical dynasties. For the rest of us, our ancestors would have been known by their name and patronymic, their father’s name, as in Abraham ben Moses or Nathan ben Israel. Indeed, Jews are still referred to in this way in the synagogue, at weddings and in prayers. But among the Sephardic community, Jewish surnames go back much further. They started to proliferate after the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of Jews in 1492. Many chose to adopt a name to help recall the places their families had left, or local landmarks and places, and passed these onto subsequent generations. Below is a list common Jewish surnames and their origins, which fall into a number of categories. I was particularly interested to discover that my own family name, Cooper, is a form of the Yiddish nickname Yankel, meaning Jacob. Patronymics: Variations on the name Abraham, including Abramovich, Avraham and Abrahams, are patronymics recalling ancestors named after the first patriarch Abraham. Jacobs and its numerous variations including Jacob, Jacobson, Jacoby, Judah, Idelsohn, Udell and Yudelson are patronyms from the Hebrew name Jacob, the third patriarch of the Jewish people. And Benjamin and Binyamin recall ancestors named after the Benjamin, the son of Jacob and Abraham’s great grandson, who founded one of the 12 tribes of Israel. Another Biblical patronymic is Isaacs or Itkowitz, meaning son of Isaac. The patronymic name Baruch comes from an ancestor named Baruch, meaning blessing in Hebrew. Perez or Peretz is another common patronymic name derived from the Hebrew name Peretz. Manishewitz, meaning son of Menashe, refers to the grandson of the patriarch Jacob who founded one of the 12 tribes of Israel. Mendelsohn and its variation Mendelovich mean son of Mendel, a variant of the Hebrew name Menachem, which means comforter, and a popular Yiddish name. In German-speaking areas, the suffix -son or -sohn was added to some names to denote ‘son of’. The suffix -ovich means the same in Russian. Kessler (also Kesel and Kesl) are thought to be a patronymic meaning son of Kesl, but may also can refer to a kestler, a Yiddish term for a married man who lives with his in-laws – a common practice among Ashkenazi families – or to a coppersmith. Matronymics: Many Jewish surnames are derived from matronyms, the that is the name of the mother rather than the father. Dvorkin and its variants including Dworin, Dwarkin and Dvarkin come from the Jewish name Devorah, meaning bee. In Biblical times, Devorah was a famed prophetess and leader who orchestrated Israel’s victory over the tyrannical Canaanite oppressors. Blum comes from the name Bluma, meaning flower in Yiddish, while Malkin, Milliken, Milken and Miliken are all matronymics of Malka, which means queen in Hebrew. Eidel and its variants Edel and Adel is derived from the Yiddish name Eidel meaning gentle or sweet. One of the first known Jews with the name Eidel was the Polish Rabbi Shmuel Eidel (1555-1631). His mother-in-law Eidel Lifschitz was a businesswoman who financially supported the yeshiva he ran for over twenty years, and he appears to have taken her name as a surname in tribute. And Margolis, Margalis and Margulis, meaning pearl in Hebrew, are derived from Margolit, the wife of the 15th century Rabbi Jacob of Nurenberg, whose descendants included many prominent religious scholars. Margolis is a more common spelling among Lithuanian Jews, while Margulis is favoured among Jews from Poland and Ukraine. Place names: While some of these are self-explanatory – Berlin referring to someone with origins in the German city, for example, and Epstein from the town of Eppstein in the German province of Hesse – many are less obvious or have additional meanings. For example, Berlin and Berliner may also be a patronymic of the name Berl, while Epstein is one of the earliest Jewish surnames – the earliest written mention of Epstein as a Jewish name comes from 1392 – and commemorated a prestigious rabbinical dynasty. Ash and Asch are a shortened version of various European towns and could refer to Aisenshtadt (Eisenstadt in modern day Austria) or Amsterdam, among others. Eisenstadt means iron town in German and is the capital of the Austrian province of Burgenland. Goldberg meaning golden town, refers to the town of Goldberg in Germany or Złotoryja/Goldberg in Poland, both once home to Jewish communities. Warshavsky and Warshauer both denote a family from Warsaw, while Wiener, Wein and Weinberg indicate someone from Vienna. Wallach can refer to someone from the German town of Wallach, but may also refer to the middle high German word walhe, which means a foreigner from a Romance country. This name is likely to have been given to Jews who migrated to Germany from Italy, or the Papal states. Similarly, Bloch or Block is derived from the old Polish word wloch, which originally meant foreigner and became a common way to refer to migrants from Italy, which had a thriving Jewish population in the Middle Ages. Montefiore is a common name originally referring to someone from the Montefiore region of Italy. Gordon can refer to the town of Grodno in Lithuania, but may also reference the Russian word gorodin meaning a town-dweller. With its easy pronunciation and non-Jewish connotations – Gordon is also a common Scottish surname – it was a popular choice among Jewish immigrants to America and the UK. Berger and Berg are common names referencing the type of place that a family came from – Berg meaning a hilly or mountainous place, while Berger often referred to someone from a town (burgh in German). Navaro and Navarro are Jewish surnames denoting someone from the Navarre kingdom of Spain before the expulsion of Jews in 1492. Many of those forced to flee adopted names to remind them of their homeland. Other names of this type include Spinoza, referring to the Spanish town of Espinosa. Kirghiz is a Turkish Jewish name related to the town of Kagizman in eastern Turkey. Interestingly, this was the maiden name of the singer Bob Dylan’s grandmother (Dylan himself was born Robert Zimmerman). Professions: Many Jewish surnames, both Ashkenazi and Sephardi, reference professions. An interesting example from North Africa is Abecassis and its variations Abiksis, Abucassis and Cassis, which incorporates a variant of the prefix Abu, meaning father of, and cassis, which means storyteller in Arabic. In past generation, a cassis was considered a profession and many North African Jews engaged in this job and adopted the surname of their profession. Surnames denoting professions have their origins in many different languages. From the German we derive Bauman, meaning builder, and Nagler, which comes from nagal, the old German word for nail. It referred to a builder or someone who made or sold nails. The Polish equivalent is Plotnick or Plotnik, also meaning builder. Goldschmidt means goldsmith in German, while Shnitzer and Schnitzer come from the German for carver. Zuckerman – from zucker, the German word for sugar – refers to a dealer in sugar or confectionary, but was also adopted by some Jewish families because of its pleasant connotations, which made it an attractive surname. Some Jewish surnames derive from the Yiddish name for occupations, such as Fishman, meaning fish-seller. Fingerhut comes from the Yiddish word for thimble, and refers to a tailor. Garfinkel or Garfunkel was probably adopted by families in the jewellery business. The name derives from the Yiddish word gorfinkl (karfunkel in German) which literally means a carbuncle, but in the past was also was used to refer to red precious stones such as rubies and garnets. In the Sephardic community, Elkayim is a Middle Eastern Jewish surname meaning tentmaker. Teboul and its numerous variations including Toubol, Touboul, Tovel and Abitbol is a popular Sephardic name indicating ancestors that may have been musicians. It derives from the Arabic tabell, a type of drum. Symbolic imagery: Among German-speaking Jews, it was popular to choose names reflecting beautiful gems or precious metals, such as Diamond and Gold. Similarly, Goldman was a popular choice among Austrian Jews for its connotation of gold and man. Eisen, meaning iron, was another popular choice for Austrian Jews. Colours were popular too, in particular Blau, meaning blue. Rosenberg – literally mountain of roses – was adopted by many Jewish families because of its beauty and evocative nature. Likewise, Rosenthal, meaning valley of roses in German, was a popular choice, in particular in the area around Minsk in present-day Belarus, where many Russian Jews favoured beautiful and symbolic Germanic names. Another popular name in the same area was Silverstein or Silberstein, meaning silver stone in German. Human or physical qualities: Several Jewish surnames were bestowed to reflect the physical characteristics or human qualities of their holders. Ehrlich, for example, was used in the Austro-Hungarian empire to denote a person who is honest. Friedman was a popular Jewish surname from the 1600s, deriving from the old Germanic word fried, meaning peace. Literally a man of peace, Friedman was used to refer to a holy person or a friend. Fogel derives from the old German word fugal meaning bird, which was used as a term of endearment. Hart or Heart is from the Germanic word hart, meaning a stag or deer, which may have symbolic connotations. Zadok and related names including Sadoc, Zadoq, Acencadoque, Aben Cadoc and Sadox are variations of the Hebrew word tzedek, meaning justice and righteous, and commonly used as surnames in Sephardic communities. Another Sephardic name, this time relating to physical appearance is Bouskila, which is derived from the Arabic word shakila, which was a distinguishing cloth, usually red and white, worn by Jews in North Africa in Medieval times. The prefix bou- or bu- means father of, and the name refers to someone who used to wear this distinctive Jewish outfit. Ashkenazi surnames relating to Physical characteristics include Gelb and Geller, which both mean yellow in Yiddish, and were often given to people with fair or even reddish hair. This blog post is based on an article on aish.com. To read the full article, click here www.aish.com/jw/s/The-Meaning-of-Some-More-Jewish-Last-Names.html  I recently read a fascinating obituary of the last musician to grow up playing traditional Jewish music in Eastern Europe before the Holocaust. Leopold Kozlowski died in March at the ripe old age of 100. Kozlowski gained fame as the “Last Klezmer of Galicia”. He was an expert on Jewish music, having taught generations of klezmer musicians and Yiddish singers in Poland. He continued to perform until shortly before he died. He was born Pesach Kleinman in 1918 in the town of Przemyslany, near Lviv, which was then in Poland and is now part of Ukraine. His grandfather was a legendary Klezmer player by the name of Pesach Brandwein, one of the most famous traditional Jewish musicians of the 19th century. With his nine sons he performed at Hassidic celebrations and even for heads of state, including the Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph. Brandwein created a musical dynasty, with many of his descendants forming family orchestras throughout Galicia. The clan also gained renown in America. Brandwein’s son, the clarinetist Naftuli Brandwein, settled in New York in 1908 and became known as the “King of Jewish Music.” Because of the family’s reputation, Brandwein’s youngest son, Tsvi-Hirsch, decided that in order to prove himself, he should change his name and go it alone. He adopted his mother’s maiden name, Kleinman, to avoid association with his famed grandfather and uncle. His son Pesach — later to be known as Leopold Kozlowski — and his brother Yitzhak would prove to be the greatest musical talents of all Brandwein’s grandchildren. Kozlowski played the accordion and later the piano, while his brother played the violin. By the 1930s, as teenagers, they began playing alongside with their father, but times were hard and most families could no longer afford to hire a band for weddings. The boys devoted nearly all of their free time to practicing and performing and were later admitted to Conservatory in Lviv, completing their studies in 1941. By this time their home town had become part of Soviet Ukraine and was flooded with Polish Jews who gave increasingly dire accounts of the situation in Nazi-occupied Poland. When Germany invaded the USSR on June 22, most believed that the Germans would only kill Jewish men of fighting age. Kozlowski’s mother told him, his brother and his father to flee. The three men travelled 200 miles on foot in a little over a week, their instruments slung over their shoulders. But they were intercepted by the German army on the outskirts of Kiev. Realising that capture meant near certain death, they searched for a place to hide, settling on a cemetery where they dug up the earth with their hands and hid in coffins alongside the dead. Finally emerging from hiding, they were immediately captured by the German army. But just as the soldiers were about to fire, Kleinman pleaded with them to allow him and his sons to play a tune. The soldiers listened, and slowly they lowered their rifles. After checking to see that no-one was watching, they gave Kleinman and his sons some food and left. The three men returned to their coffins. Unable to remain among the dead any longer, and with no other option open to them, they eventually headed home, travelling by night and hiding in the forest by day. Three times German soldiers captured them, and each time they were released after playing a song. Back in Przemyslany, the Gestapo ordered all Jews over 18 to assemble in the marketplace. From there the Germans led 360 Jews into the forest where they were forced to dig their own graves and then shot. Among them was Kleinman, while his wife was murdered soon afterwards when German soldiers found her hiding in a nearby barn. Kozlowski and his brother attempted to flee, but were quickly captured and sent to the Kurovychi concentration camp near Lviv. Both brothers soon joined the camp’s orchestra and when SS officers learned of Kozlowski’s skill as a composer, they ordered him to compose a “Death Tango” to be played by the orchestra every time Jews were led to their execution. The officers would bring the brothers to their late-night drinking sessions and command them to play. They were frequently made to strip naked and the Germans extinguished cigarettes on their bare skin. Eventually the two men joined a group that planned to escape. They befriended a Ukrainian guard with a drinking problem, and while the brothers distracted a group of SS officers with their music, a third prisoner stole a bottle of vodka from them and gave it to the guard while he watched over the camp fence. Once the guard passed out, the inmates grabbed his wire cutters and made a hole in the barbed wire. Immediately the camp’s searchlights fired up and gunfire reverberated. Several inmates were mown down by bullets just outside of the fence; others were caught by guard dogs and executed. Running alongside his brother with his accordion over his shoulder, Kozlowski felt several sharp jabs in his shoulder. When he examined his accordion later, he found multiple holes; the accordion had blocked the bullets’ path, leaving him unscathed. The accordion is now on display at the Galicia Jewish Museum in Krakow. Following their daring escape, the brothers joined a Jewish partisan unit and later a Jewish platoon of the Home Army. In 1944 Kozlowski’s brother was stabbed to death having stayed behind from a mission to guard injured comrades, and Kozlowski never forgave himself for being unable to save him. Throughout the horrors of their wartime experiences, the brothers had continued to play music. Music not only saved Kozlowski’s life several times, but also helped heal his psychological wounds, his long-time friend, the American klezmer artist Yale Strom, said in an interview. After the war Kozlowski settled in Krakow and enlisted in the army. Still fearful of anti-Semitic violence, especially after the massacre of Jews in Kielce in July 1946, he exchanged his Jewish surname for the Polish Kozlowski. He served in the military for 22 years, achieving the rank of colonel and conducting the army orchestra. In 1968 he once again fell victim to anti-Semitism when he was discharged under President Wladyslaw Gomulka’s anti-Semitic campaign. “He thought to himself: ‘I’ve already changed my name, already hidden my identity and I’ve served more than 20 years in the Polish army and yet I’m still considered ‘the Jew,’” Strom said. “‘I’d be better off not hiding anymore. I might as well play Jewish music.’” At a time when most of Poland’s remaining Jews fled the country, he joined the Polish State Yiddish Theatre and began composing original scores and coaching actors to sing with an authentic Yiddish intonation. He also played at celebrations for Krakow’s Jewish community and taught children Yiddish songs. Under perestroika as the Soviet Union began to release its iron grip, Kozlowski was able to connect with klezmer musicians abroad, and in 1985 he visited the US where he met the leaders of the nascent klezmer revival movement. Later, Stephen Spielberg met Kozlowski in Krakow while scouting locations for his film Schindler’s List. The two hit it off and Spielberg hired him both as a musical consultant for the film and to play a small speaking role. Strom released a documentary, “The Last Klezmer: Leopold Kozlowski, His Life and Music,” in 1994, transforming Kozlowski into a celebrity in Poland. In old age, Kozlowski’s fame continued to grow. As well as international festival appearances and his regular concerts at the Krakow restaurant Klezmer Hois, he gave an annual concert with his students as part of Krakow’s international Jewish cultural festival. Even at 99 he was still the star of the show, playing the piano for two hours. In his final years, Kozlowski spent much of his time in Kazimierz, Krakow’s historic Jewish quarter, which has become a tourist attraction. He often received visitors from abroad at his regular table at Klezmer Hois. Among the Jewish cemeteries, synagogues that function primarily as museums, and quasi-Jewish restaurants, Kozlowski himself became a sort of tourist attraction, the last living link to the music of pre-war Jewish life. I can only wish that I had chanced upon him when I visited Kazimierz last summer. This is an abridged version of a piece that appeared in The Forward. Click here to read the full article. https://forward.com/culture/423976/klezmer-leopold-kozlowski-holocaust-survivor-spielberg-schindlers-list/  Ten years ago I travelled with my Dad to America for a family visit. It was the first time I had met most of his first cousins – and it turned out to be the last time I saw his sister, my dear aunt Lil, who died a few years later. One of Dad’s relatives, irrepressible and wonderful cousin Betty, is a psychic and clairvoyant. Betty is much on my mind at the moment as wildfires rage around Los Angeles, forcing her to evacuate her home. “I know you are a writer, but have you ever thought about doing documentaries?” she asked me back in 2008. “I’d love to make documentaries!” I replied. “Well, you will.” And today, ten years on, the first documentary I have been involved in is being broadcast on the BBC's World Service radio station. It’s a ten-minute piece about the lost Jewish world of the Eastern European shtetl, using anecdotes recounted by my grandmother about her early life back in Ukraine – then part of the Russian Empire. Mostly when I give talks about my work, I focus primarily on the dramatic major events that affected Russia’s Jewish community at the time – pogroms, World War I, the Russian Revolution and civil war. But the documentary concentrates on more mundane aspects of day-to-day life, such as Sabbath rituals in my grandmother’s house, relations with the local Ukrainian population, the Rabbi’s court where members of my family lived and worked, and a crazy and somewhat comical incident that landed my great-great grandmother in jail, to the horror and embarrassment of the whole family. The documentary is based on snippets of recordings made by my father back in the 1970s of my grandmother telling stories about her early life in Russia. They are recorded in Yiddish, the language of the Jews of Eastern Europe. It is a language once spoken by around 12 million people that transcended national boundaries, but which was almost wiped out by the holocaust. The vast majority of the Jews killed in the Nazi death camps would have spoken Yiddish as their mother tongue. Today the language is undergoing something of a revival, in the US in particular. Surprisingly there are still up to two million Yiddish speakers in the world. You can sign up to Yiddish evening classes, watch Yiddish theatre performances and attend Yiddish dance parties. In 2017, the Yiddish Arts and Academics Association of North America was born, with a mission to promote Yiddish language and culture through academic and artistic events and through Yiddish food. “The goal,” says founder Jana Mazurkiewicz Meisarosh, “is to make Yiddish culture hip, modern and interesting.” In the US, “Yiddish has been trapped within two discrete, hermetic spheres: the ultra-Orthodox sphere, which engages the religious aspects of Yiddishkeit, and the academic sphere, which tends to study secular Yiddishkeit of the past. As a result, Yiddish language and culture … is often viewed as a relic of the past, and fails to find resonance in daily life and modern culture,” she says. It’s a fascinating and worthy goal, to bring back to life a language that came close to extinction. The culture of the shtetl is unlikely to be reborn outside of the most restrictive Jewish communities, but if it can gain further resonance in today’s world, this is surely something to celebrate. Listen to the documentary here: www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/w3cswsp3  I was in London last week to record a radio documentary for the BBC. The programme, Witness, describes events in history using the voices of people who lived through them. The producer was interested in my grandmother’s stories of the lost Jewish world, as recorded by my father in the 1970s. At that time, Dad was a social historian working at the University of East Anglia in Norwich, England, and Grandma was a tiny, frail old lady in her late 70s, living in Los Angeles. Dad had grown up with his mother’s stories of her early life in Russia and, as an adult and an academic, he wanted to probe deeper into the Jewish community in which she had lived. Over the course of the years that followed, some of the audio tapes Dad recorded became distorted, broken, lost or accidentally re-recorded with pop music (my brother and I were teenagers, we wholeheartedly apologise), but enough remained to ensure that my grandmother’s stories were not lost. Until about 15 years ago I had never listened to these cassettes. They were recorded in Yiddish, a language I don’t understand, and as a youngster I was never sufficiently interested to ask my father to translate them. I had no idea what a rich and fascinating history they would reveal. Even Dad had not revisited the tapes for years. When my father reached his 70s, I began to fear that the stories would be lost. It was a labour of love for the two of us to listen to the cassettes one by one and piece together a story. Hour after hour Dad translated while I typed. These transcripts eventually became the basis for my book, A Forgotten Land. After we had finished translating and transcribing the recordings, Dad put the cassettes away and I did not see them again until I came across them tucked away in a drawer when we cleared Dad’s flat after he died in 2012. I brought them home and put them away in a box with some other items of Dad’s that I kept – some photos, newspaper clippings and the family Kiddush cups. And there they stayed for the next six years. Before my trip to London, I needed to identify the sections of the recordings that would go out on air. First I had to borrow an old tape recorder, and cross my fingers that it didn’t chew up the audio tape. I spent several days listening to the cassettes, digitising them and trying to work out which story was which, listening out for names and places (Bolsheviki, Kerensky, Kiev, Libau), family members, familiar Russian words and anything in Yiddish that my rudimentary knowledge of German was able to pick up. Thankfully I found some of my early transcripts, which were a great help. But as Dad didn’t number the tapes as he recorded or replayed them, everything was utterly jumbled. Eventually I managed to pick out the four short segments that the radio producer wanted to use. At the recording studio, I talked around these stories, filling in background and adding details. When I had finished, an actress arrived to record voice-over translations. She began talking with a theatrical flourish and a mild Russian accent. “No, no,” the producer said. “This is a very simple woman, an uneducated woman, recounting events to her family. Tone it down!” The final result will be broadcast on the BBC World Service in the coming weeks. I wait with bated breath! I recently came across a surprisingly interesting series of articles about Jewish surnames from the Russian Empire. It turns out that there’s much more to this dry-sounding subject than meets the eye.

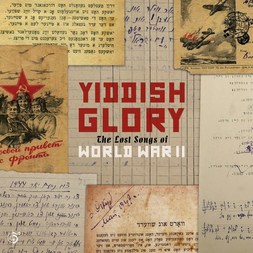

In Eastern Europe, Jews acquired their last names between the end of the 18th century and the middle of the 19th, following a series of laws forcing them to adopt hereditary names. Before that, the only Jews with surnames were those belonging to certain rabbinical dynasties. For the rest of us, our ancestors would have been known by their name and patronymic, their father’s name, as in Abraham ben Moses or Nathan ben Israel. Surnames across the Russian Empire have their roots in several different sources. Those derived from towns or cities in western Germany, such as Auerbach, Epstein, Ginzburg, Halpern, Landau and Schapiro were particularly prestigious, passed down through rabbinical families living in western Germany during the 15th and 16th centuries before they or their descendants migrated eastwards. The high frequency of the name Epstein, for example, results from its old age; the earliest reference, from Frankfurt, dates from 1392, and the migration of a rabbi bearing this name to Eastern Europe. It is testimony to the prestige of his lineage rather than a large number of migrants from the town of Eppstein. Unusually, many were derived from women’s first names, such Belkin, Dvorkin, Malkin, and Rivkin – derived from Belka (Beyle), Dvorka (Deborah), Malka, and Rivka – far more than prevailed outside the Russian Empire. This may be partly because it was often Jewish women who were outwardly facing in areas like commerce and the marketplace, while their menfolk studied in Yeshiva or worked from the home as craftsmen. Many women would have been better known to the inhabitants of a locality than their husbands. Additionally, a tradition already existed in Eastern Europe before the 19th century of giving men ‘nicknames’ based on female first names, for example, the famous Polish rabbis Samuel Eidels (1555-1631) and Joel Sirkes (1561-1640), both ending in the Yiddish possessive suffix -s. Numerous names of the community leaders in Lviv found in Polish documents from the 1740s–1770s belong to the same category: Bonis, Cymeles, Daches, Fayglis, Menkes, Minceles, Mizes, and Nechles. This naming tradition could have had a direct influence on the names adopted at the turn of the 18th-19th centuries in the same area, as well as in southern Ukraine and Bessarabia. Just how common these matronymic names were once Jews were required by law to adopt surnames varies from place to place. Surnames based on female names were particularly common in the Mogilev province in eastern Belorussia, where they covered 30-40 percent of the Jewish population. Almost all of them were created by using the East Slavic possessive suffix –in. In many other areas the percentage is only in single figures. The naming process was administered by the Jewish administration, the Kahal, and it is likely that local Kahal authorities were largely responsible for choosing a model for the distribution of surnames, some choosing to follow matronymic lines, others opting for other patterns. In the Novogrudok district of Minsk province, one third of Jews received names derived from male given names and for another third surnames were drawn from local place names by adding the suffix -sky. In a number of districts of Volhynia and Podolia, artificial surnames with attractive meanings like Goldberg ‘gold mountain’, Rosenthal ‘valley of roses’, and Silberstein ‘silver stone’ covered about one third of all names, while one quarter of names indicated the occupations of their first bearers. In the area southeast to Kiev, two thirds of Jews received names ending in -sky based on local towns. Less likely to be true, according to Alexander Beider, a linguist and expert on the subject of Jewish names, is the common perception that Jews paid money for the best names – the attractive ones like the above-mentioned Goldstein, Rosenthal or Silberberg. The widespread nature of attractive-sounding names, and the relative scarcity of derogatory ones supposedly assigned to those too poor to pay a bribe, would appear to debunk this myth. In addition, Beider says, the existence of a list of names and their bribe price across a wide area covering different jurisdictions is simply not feasible. This post is based on a series of articles in The Forward by Alexander Beider, a linguist and the author of reference books about Jewish names and the history of Yiddish. For more see: https://forward.com/opinion/395078/why-do-so-many-jewish-last-names-come-from-women/d.com/opinion/395078/why-do-so-many-jewish-last-names-come-from-women/ And: https://forward.com/opinion/391341/did-jews-buy-their-last-names/  A few years ago, a hoard of songs written by Jewish men, women and children killed in World War II came to light in Kiev. The songs, in Yiddish, are haunting, raw and emotional testimonies by ordinary people experiencing terrible events. They are grassroots accounts of German atrocities against the Jews, with subjects that include the massacres at Babi Yar and elsewhere, wartime experiences of Red Army soldiers, and those of concentration camp victims and survivors. One song was written by a 10-year old orphan who lost his family in the Tulchin ghetto in Ukraine, another by a teenage prisoner at the Pechora concentration camp in Russia’s far north. The songs convey a range of emotions, from hope and humour to despair, resistance, and revenge. The project to collect these songs is as remarkable as the music itself. It began when a group of Soviet scholars from the Kiev cabinet for Jewish culture, led by the ethnomusicologist Moisei Beregovsky (1892-1961), made it their mission to preserve Jewish culture in the 1940s. They recorded hundreds of Yiddish songs written by Jews serving in the Red Army during the war; victims and survivors of Ukrainian ghettoes and death camps; and Jews displaced to Central Asia, the Urals and Siberia. Beregovsky and his colleagues hoped to publish an anthology of the songs. But after the war, the scholars were arrested during Stalin’s anti-Jewish purge and their work confiscated. The story could so easily have ended there; indeed the researchers went to their graves assuming their work had been destroyed. Miraculously the songs survived and were discovered half a century later. They were discovered in unnamed sealed boxes by librarians at Ukraine’s national library in the 1990s and catalogued. Then in the early 2000s Professor Anna Shternshis of the University of Toronto heard about them on a visit to Kiev and brought them to light. Some were typed, but most handwritten, on paper that was fast deteriorating. Most consisted just of lyrics, although some were accompanied by melodies. The songs were performed for the first time since the 1940s at a concert in Toronto in January 2016, and are shortly to be released by record label Six Degrees. Artist Psoy Korolenko created or adapted music to fit the lyrics, while producer Dan Rosenberg brought together a group of soloists, including vocalist Sophie Milman and Russia’s best known Roma violinist Sergei Eredenko, to create this miraculous recording. “Yiddish Glory gives voice to Jewish children, women, refugees whose lives were shattered by the horrific violence of World War II. The songs come to us from people whose perspectives are rarely heard in reconstructing history, none of them professional poets or musicians, but all at the centre of the most important historical event of the 20th century, and making sense of it through music,” Shternshis says. Yiddish Glory: The lost songs of World War II will be released on 23 February. For more information see: https://www.sixdegreesrecords.com/yiddishglory/ |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed