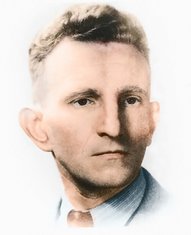

Ukraine’s policy of celebrating its nationalist ‘heroes’ continues, with plans to rename a main Kiev street after Roman Shukhevych, a Ukrainian paramilitary leader responsible for the massacre of tens of thousands of Poles and Jews. The city council passed the decision on 1 June with 69 of 120 members voting in favour. The street was previously named after Red Army general Nikolai Vatutin, who had been involved in liberating Kiev from the Nazis. Hundreds of citizens gathered in front of the statue of Valutin in the centre of Kiev, many of them World War II veterans, shouting “Shame”. Violence broke out after the demonstrators were attacked by ultra-nationalists and 20 people were injured. Shukhevych (see photo) was a Ukrainian politician and paramilitary leader, who headed the Ukrainian Insurgent Army during and after World War II. The nationalist militant organisation was for a time allied to Nazi Germany and was responsible for the mass slaughter of Poles and Jews. The proposed street-name change is the latest in a line of events in which Ukraine has honoured controversial nationalist heroes. In 2015 the country even passed a law celebrating Shukhevych’s Ukrainian Insurgent Army and its parent organisation, the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists. Streets elsewhere in the country have been named after the group and its leaders. Ukraine’s Institute of National Memory is drafting a law to posthumously exonerate members of both organisations who were convicted of murdering Polish and Jewish civilians during and after the war. In October 2009, then-president Viktor Yushchenko honoured Shukhevych with the title Hero of Ukraine. In Lvov, a festival celebrating Shukhevych, featuring music and theatre, is due to be held today, on the anniversary of a major pogrom against the city’s Jewish population. On 30 June 1941, Ukrainian troops, including militias loyal to Shukhevych, initiated a series of anti-Semitic attacks under the auspices of the German army, in which up to 6,000 Jews were murdered. Shukhevychfest also marks the 110th birthday of the nationalist leader. Edward Dolinksy, one of the leaders of Ukraine’s Jewish community, called the street-name change “a case of moral decline, cynicism and contempt for humanity”. “This is a day of national shame,” he said. Kiev’s regional court has issued an interim injunction temporarily prohibiting the name change, following an appeal by the Jewish community. Many Ukrainians view the country’s wartime nationalist leaders as heroes in the fight for an independent Ukraine. But their veneration has coincided with a growing number of anti-Semitic incidents in Ukraine – see my blog post dated 5 May and 3 March. Kiev’s mayor, Vitali Klitschko, whose grandmother was Jewish, has come under pressure to veto the city council’s decision, but has failed to intervene, even though he reportedly is not in favour of the move. Ukraine’s Jewish prime minister, Petro Poroshenko, has remained silent on the issue. Poroshenko was in Washington last week for a meeting with President Donald Trump for talks on security, political and economic issues. The Ukrainian leader emerged from the meeting saying Kiev had “received strong support from the US side” over sovereignty, territorial integrity and the “independence of our state”. But Trump failed to speak out about Ukraine’s troubling glorification of Nazi collaborators. The President has faced accusations at home that he is soft on anti-Semitism and has not taken steps to distance himself from neo-Nazi groups that supported his election campaign.

0 Comments

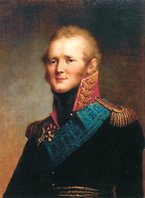

I was interested to read this week that the Israeli government is planning to discuss once again the fate of the so-called Subbotniks living in Russia and Ukraine, descendants of Russian peasants who converted to Judaism over 200 years ago. The Subbotniks have been oppressed on two fronts – persecuted at home for being Jews, but recently considered insufficiently Jewish to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. Israel’s committee on immigration and absorption is due to debate the issue of the Subbotniks soon, and many members of the community are hoping for a ruling in their favour that will enable them to join family members already in Israel. The origins of the Subbotniks are hazy. They date back to the late 18th century, during the reign of Catherine the Great, when a group of peasants in southern Russia distanced themselves from the Russian Orthodox Church and began observing the Jewish Sabbath – hence their name, derived from the Russian Subbota (Суббота), meaning Saturday, or Sabbath. Their descendants celebrate Jewish holidays, attend synagogue and observe the Sabbath. But it is not clear whether their forefathers officially converted to Judaism, and once in Israel, Subbotniks are still considered non-Jews until they undergo conversion. Many do not recognise the term Subbotnik – they consider their families to have been Jewish for many generations, and have been persecuted for their faith – and cannot understand Israel’s position. In the early 19th century, Tsar Alexander I (see photo) deported the Subbotniks to various parts of the Russian empire, leaving small communities scattered across a wide area. For this reason, Subbotniks today can be found as far apart as Ukraine, southern Russia, the Caucasus and Siberia. A first wave of Subbotnik emigration took place in the 1880s, when many fled persecution to settle in what was then part of Ottoman Syria, now Israel. Anti-Semitic pogroms broke out in Russia in the early 20th century, prompting another wave to emigrate. Many more Subbotniks left the Soviet Union and its successor states after the fall of the Berlin Wall, part of the more than million-strong flood of Soviet Jews who immigrated to Israel at that time. Some prominent Israelis are descended from Subbotnik settlers – among them former prime minister Ariel Sharon. But Israel’s Chief Rabbinate later claimed that the Subbotniks’ Jewish origins were not sufficiently clear, and that they would have to undergo conversion to Orthodox Judaism, thereby making them ineligible for aliyah to Israel – the automatic right to residency and Israeli citizenship that is available to all Jews. Some Subbotniks were granted the right to immigrate in 2014, but around 15,000 are estimated to still live in the former Soviet Union, most of whom desire to immigrate to Israel. The biggest Subbotnik community today is still in the area around Voronezh, where the movement began. It’s a city I know well, having spent a year as a student there in the 1990s.  The two focal points of the Russian Revolution of 1917 centre on the February Revolution, when the Tsar was deposed, and the October Revolution, when the Bolsheviks seized power. But deep political changes and revolutionary fervour continued to bubble away between those key events. In early June, 100 years ago, Kiev’s central Rada, which had formed in March, proclaimed an independent Ukraine. The decision was supported by the first All-Russian Congress of Soviets, which had recently begun its session in Petrograd. The Congress voted in favour of Russia’s minority nations and peoples’ right to self-determination. It also resolved to negotiate with Russia’s allies for an immediate end to the war. Alexander Kerensky, who would later become prime minister, had just been named minister of war and launched a fresh offensive on the eastern front that brought devastating losses. Estimates put the number of deaths at 150,000, with some 250,000 wounded, prompting huge Bolshevik-led demonstrations in support of peace. Some 400,000 workers joined the protests in cities across Russia and Ukraine. As well as Moscow and Petrograd, Kiev and Kharkov saw some of the biggest peace marches. Factory workers staged massive strikes demanding an end to the war and food for the starving at home. The events of June 1917 lead the way for the so-called July Days, when hundreds of thousands of workers took to the streets of Petrograd demanding “All power to the Soviets!”. Armed clashes ensued and several hundred people were killed or wounded as troops attempted to break up the demonstrations (see photo). The protests were followed by mass arrests and violence. My grandmother Pearl was far away from Petrograd, in the small town of Pavolitch, around 60 miles from Kiev. Here’s what she said in A Forgotten Land about this period: “Prices continued to rise by the month, even by the week, until even bread became a luxury. How grateful we were for my grandfather’s grain supplies [Her grandfather was a grain dealer]. But with the incoming cartloads from the peasants dwindling, he was forced to raise his prices. The townsfolk were so desperate that they had no choice but to pay – or else go hungry. The bakers ground my grandfather’s wheat with chestnuts and potato peelings and baked bread that was so glutinous it stuck to the gums and was almost impossible to swallow. “Zayde’s [Grandfather’s] trips to Kiev became rare, but he recounted stories of the increasing unrest he witnessed each time he returned. People talked openly, fearlessly, in the streets about Russia withdrawing from the war and abandoning her allies; power to the workers; people’s soviets. Students handed out leaflets and waved red banners. What did it all mean? Would the war soon be over? How can workers take power? And what were the soviets? To a fifteen year old girl in a small country town, the reports from the city were all very mysterious.” |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed