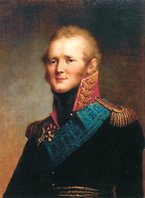

I was interested to read this week that the Israeli government is planning to discuss once again the fate of the so-called Subbotniks living in Russia and Ukraine, descendants of Russian peasants who converted to Judaism over 200 years ago. The Subbotniks have been oppressed on two fronts – persecuted at home for being Jews, but recently considered insufficiently Jewish to be allowed to immigrate to Israel. Israel’s committee on immigration and absorption is due to debate the issue of the Subbotniks soon, and many members of the community are hoping for a ruling in their favour that will enable them to join family members already in Israel. The origins of the Subbotniks are hazy. They date back to the late 18th century, during the reign of Catherine the Great, when a group of peasants in southern Russia distanced themselves from the Russian Orthodox Church and began observing the Jewish Sabbath – hence their name, derived from the Russian Subbota (Суббота), meaning Saturday, or Sabbath. Their descendants celebrate Jewish holidays, attend synagogue and observe the Sabbath. But it is not clear whether their forefathers officially converted to Judaism, and once in Israel, Subbotniks are still considered non-Jews until they undergo conversion. Many do not recognise the term Subbotnik – they consider their families to have been Jewish for many generations, and have been persecuted for their faith – and cannot understand Israel’s position. In the early 19th century, Tsar Alexander I (see photo) deported the Subbotniks to various parts of the Russian empire, leaving small communities scattered across a wide area. For this reason, Subbotniks today can be found as far apart as Ukraine, southern Russia, the Caucasus and Siberia. A first wave of Subbotnik emigration took place in the 1880s, when many fled persecution to settle in what was then part of Ottoman Syria, now Israel. Anti-Semitic pogroms broke out in Russia in the early 20th century, prompting another wave to emigrate. Many more Subbotniks left the Soviet Union and its successor states after the fall of the Berlin Wall, part of the more than million-strong flood of Soviet Jews who immigrated to Israel at that time. Some prominent Israelis are descended from Subbotnik settlers – among them former prime minister Ariel Sharon. But Israel’s Chief Rabbinate later claimed that the Subbotniks’ Jewish origins were not sufficiently clear, and that they would have to undergo conversion to Orthodox Judaism, thereby making them ineligible for aliyah to Israel – the automatic right to residency and Israeli citizenship that is available to all Jews. Some Subbotniks were granted the right to immigrate in 2014, but around 15,000 are estimated to still live in the former Soviet Union, most of whom desire to immigrate to Israel. The biggest Subbotnik community today is still in the area around Voronezh, where the movement began. It’s a city I know well, having spent a year as a student there in the 1990s.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed