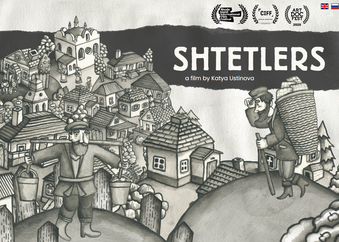

The story of the Jewish shtetl is well known. These once vibrant communities that were so widespread across Eastern Europe until the 20th century were destroyed, first by pogroms and resulting waves of emigration, and later by the anti-religion policies of the Soviet Union, with their final remnants wiped off the face of the earth by the Holocaust. But not so, it seems. A new documentary from the Russian filmmaker Katya Ustinova explores the existence of shtetls in Ukraine and Moldova right up until the 1970s and even beyond. Shtetlers premiered last year and was available to view during Russian Film Week USA in January. Unfortunately, is not yet available in Europe, so I am still awaiting an opportunity to watch it. As the film’s website says, “In those small and remote towns of the Soviet interior, hidden from the world outside of the Iron Curtain, the traditional Jewish life continued for decades after it disappeared everywhere else. The tight-knit communities supported themselves by providing goods and services to their non-Jewish neighbours. The ancient religion, Yiddish language and folklore, ritualised cooking and elaborate craftsmanship were practised, treasured and passed through the generations until very recently.” Ustinova is a Russian-born documentary maker living in New York who previously worked as a producer, host and reporter for a Russian broadcasting company in Moscow. Shtetlers is her first feature-length film. Ustinova’s grandfather was a Jewish playwright, but her family did not identify as Jewish until her father, a businessman and art collector, founded the Moscow-based Museum of Jewish History in Russia in 2012. On discovering modern artifacts from shtetls in the former Soviet Union, Ustinova and her father came to realise that some Jewish communities had continued to exist for far longer than they had thought. Shtetlers tells the stories of Jews in these forgotten shtetls by means of nine first-hand accounts of people who lived in them. In 2015, Ustinova visited several former shtetl residents, who have since scattered around the world. Many of the stories in Shtetlers help break down the myth that only enmity existed between Ukrainians and Jews. Without distracting from the fact that many Ukrainians committed atrocities against the Jewish population before and after – as well as during – the war, the film reminds us of those gentiles who loved and cared for their Jewish friends and neighbours. Meet Vladimir. He was not born Jewish, but converted after his mother – who is honoured at the Yad Vashem Holocaust Remembrance Centre – sheltered dozens of Jews during the war. Growing up among Jewish neighbours, their culture imbued itself into gentile homes, and he remembers his mother baking challah during his childhood. Vladimir emigrated to Israel and now lives in the West Bank as part of an Orthodox Jewish family. And Volodya and Nadya, Ukrainian farm workers still resident in a former shtetl in Ukraine, who remembered their Jewish neighbours so fondly that they decided to adopt Jewish customs, like making matzo brei and kissing the mezuzah attached to the doorway of their house – which once belonged to Jews – when they enter. Emily, a Jewish shtetler who survived the war, escaped from a concentration camp and was saved by a gentile friend – the sister of a Ukrainian police chief – who brought her family food while they were in hiding. And then there’s the queue of Russian Orthodox Christians coming to Rabbi Noah Kafmansky to solve their problems and obtain his blessing, because “the Jewish God helps better”. In the five years since Ustinova filmed Shtetlers, many of the people she met have passed away. “Their memories are a farewell to the vanished world of the shtetl, a melting pot of cultures that many nations once called their home,” the website says. The trailer is available on the Shtetlers website: shtetlers.com/ And numerous extracts from the film, as well as some gorgeous animated clips, can be found on the Shtetlers Instagram page: www.instagram.com/shtetlers/

1 Comment

I recently watched a film adaptation of French author Irène Némirovsky’s marvellous World War Two novel Suite Française. It’s a fabulous book and I have written about it before, here. The novel was written in 1941-42, while Némirovsky was living in the village of Issy-l’Eveque, having fled Paris when war broke out. The author envisaged a book of five parts, a mammoth work of a thousand pages constructed like a symphony, taking Beethoven’s Fifth as her model. She wanted it to convey the magnitude of what she was living through, not in terms of battles and politicians, but by evoking the domestic lives and personal trials of the ordinary citizens of France. The five stories would be separate but linked, with a handful of characters weaving in and out of the narrative. She completed only the first two sections before her arrest. The first depicts a disparate collection of Parisians as they flee the Nazi invasion and make their way through the chaos of wartime France, while the second follows the inhabitants of a small rural community living under Nazi occupation. Némirovsky’s parents had been wealthy, assimilated Russian Jews who fled the St Petersburg high life in December 1917 – having lost their fortune following the Bolshevik revolution – and settled in Paris, a city that was already home to many Russian emigrees who opposed the new regime. A lonely, solitary child whose mother showed her not the slightest sign of love, Irène grew up to despise and disdain her parents’ prosperous Jewish milieu. Once in Paris, she enrolled at the Sorbonne and soon became an acclaimed writer, publishing her first novella in 1927. Titled L’Enfant Genial, it told the story of a Jewish boy from the slums of Odessa who seduces an aristocrat with his poetry. In 1939, in light of the increasing likelihood of war and violent anti-Semitism across Europe, she and her children converted to Catholicism. But this was not enough to save her. She was first taken to the concentration camp at Pithiviers, in the Loiret region south of Paris on 13 July 1942, then deported to Auschwitz the following day, where she died on 17 August. That Némirovsky’s children survived the war was nothing short of a miracle, and all the more so that they kept what they thought was their mother’s wartime diary – written in tiny handwriting to save ink and paper – as a memento, guarding it carefully as they fled from one hiding place to another. The two girls did not read their mother’s work, finding it too painful to look at, until decades later when they discovered not notes or a diary, but a literary masterpiece. Suite Française was finally published in French in 2004 and in English two years later. The film, from British director Saul Dibb and starring Kristin Scott Thomas and Michelle Williams, was released in 2015. It deals only with the second story in the book, set in the fictional village of Bussy, where the affluent middle-class Angelliers are forced to play host to a German officer during the occupation. Tim Robey, reviewing the film in The Daily Telegraph, described Scott Thomas – playing the senior of the two Angellier ladies – as “more terrifying than the Nazis”. Némirovsky’s description of her character is more impressive even than Scott Thomas’ portrayal: “This older woman had such a transparent, pale face that she seemed to have not a drop of blood beneath her skin; her hair was pure white, her mouth like the blade of a knife, her lips almost purple. An old-fashioned high collar made of mauve cotton, held rigid by stays, covered but didn’t hide her sharp, bony neck which pulsated with emotion like a lizard. When she heard a German soldier’s footsteps or voice near the window, she would tremble from the tips of her small pointy little boots to the top of her impressively coiffed head.” Ma Angellier’s son Gaston is a prisoner of war and she holds each and every German personally responsible for his fate. Imagine her horror, then, when her daughter-in-law falls in love with the officer billeted in Gaston’s study. Robey in his review describes the film as a “jarringly sweet Second World War romance… It is thoroughly easy to sit through, when it should probably have been harder”. He is absolutely right, the film is entertaining enough to watch, but it fails to show any of the cynicism, ambiguity and complexity of Némirovsky’s novel – and it changes the ending in such a way that pushes it far beyond the realms of realism or possibility. The upshot – read the book, and watch the film if you like, but don’t accept it as an accurate representation of the author’s intentions. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed