When Hamas terrorists entered southern Israel last month, they committed the biggest mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust. That on its own is a desperately chilling thought. But Israel’s response to the attacks has unleashed a wave of antisemitism around the globe on a scale not seen since the middle of the last century. Words that for decades have been unsayable in public are now being chanted in the streets of our major cities. And in Russia, a country with a devastating history of antisemitism that had until recently been quashed, pogroms have broken out once again. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jews in Russia suffered wave after wave of pogroms – anti-Jewish riots that involved terrorising communities, attacking Jewish homes and businesses, humiliating and maiming, rape and murder. Last weekend Russia witnessed its first pogrom in sixty years. In Dagestan, a mainly Muslim region of southern Russia bordering Chechnya, an angry mob shouting antisemitic slogans stormed the airport of the regional capital Makhachkala. The rioters broke through security barriers onto the runway with the intention of attacking passengers arriving from Tel Aviv, fuelled by rumours circulating on social media that the plane was carrying refugees from Israel. The rumours were later proven to be untrue. Elsewhere in Dagestan, a riot broke out outside a hotel in the city of Khasavyurt, because Israeli refugees were believed to be sheltering inside. The protestors pinned a sign to the door: Entry strictly forbidden to Israelis (Jews). And in Nalchik - located, like Dagestan, in the North Caucasus region - a mob attacked and set alight a Jewish cultural centre that was under construction. The words Death to Jews were daubed on its wall. These events took place in spite of strict rules prohibiting public demonstrations in Russia, implemented to stifle protest against the war in Ukraine. The pogroms of the past took place across the Pale of Settlement, where Jews were restricted to living in Tsarist times – in present day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and the western fringes of Russia. These regions had been absorbed by Russia during the partitions of Poland under Catherine the Great in the late 18th century. Jews had long been present in great numbers in Poland because its liberal policies contrasted with most other parts of Europe at the time; Jews were welcomed for their skills in commerce that helped bolster the economy. But Russia was far less tolerant and pogroms were a direct result of an official policy of antisemitism. Today’s pogroms in Dagestan derive from sympathy with Palestinians under Israeli bombardment in Gaza. With a mostly Muslim population, Dagestan has historically been more closely aligned with the Middle East than with Russia. But it is also home to Russia’s oldest Jewish community. Jews have lived in the region since Biblical times and as Jews from elsewhere in Russia have emigrated in huge numbers, mostly to North America and Israel, Dagestan today is home to Russia’s largest Jewish community. Just as the pogroms of the past were a manifestation of official antisemitism in the Russian Empire, the pogroms in Dagestan reflect a change in sentiment in the echelons of power in Moscow. While the Vladimir Putin of the past spoke out against holocaust denial and xenophobia, the Russian president has in recent months ratcheted up antisemitic rhetoric as a reaction to Russia’s failings in the war in Ukraine, not least with his derogatory comments about Ukraine’s Jewish president Volodymyr Zelensky (see my article on the subject here). Putin’s reaction to the violence in Dagestan has been to blame Ukraine and the West, accusing Russia’s enemies of fomenting unrest to destabilise the country. The violence in Dagestan continues a worrying trend for Putin, demonstrating again how his authority is being undermined. Having risen to power almost a quarter of a century ago, Putin cemented his popularity with a reputation for restoring Russia’s territorial integrity and stability after the chaotic unravelling of the 1990s. It was his quelling of violence in Dagestan and neighbouring Chechnya that helped reinforce the strongman image that the president has sought to project ever since. But Putin’s obsessive focus on trying to destroy Ukraine has led him to turn a blind eye to unrest in Russia’s provinces that threatens to undermine his reputation and the sense of order and stability that he has so painstakingly nurtured. The attempted mutiny in June by his once loyal ally Yevgeny Prigozhin was the first clear manifestation of Putin’s authority beginning to unravel. Unrest in the North Caucasus may be the next.

0 Comments

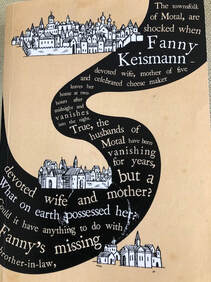

Moscow’s former chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, has urged Russian Jews to leave the country while they still can, warning that they may become scapegoats for difficulties caused by the war in Ukraine. Goldschmidt – who resigned in July because of his opposition to the war and lives in exile – pointed to numerous historical precedents for today’s rising antisemitism. “When we look back over Russian history, whenever the political system was in danger you saw the government trying to redirect the anger and discontent of the masses towards the Jewish community,” he told The Guardian. “We saw this in tsarist times and at the end of Stalin’s regime.” Antisemitism was rife under the tsars, and waves of pogroms in 1881-1906 were condoned by the tsars, if not actually encouraged by them. Often the police were ordered not to intervene, and sometimes even joined in the antisemitic attacks and looting. Up to two million Jews left Russia as a result of the pogroms. Attacks on Jewish communities peaked in 1919 during the Russian civil war, in Ukraine in particular, when numerous different factions fought for control of the land. All of them committing acts of violence against Jews who were blamed both for food scarcity and rising prices, and for supporting the Bolsheviks. Discrimination and antisemitism prompted many Jews to back the Bolshevik regime, which banned religion of any kind and proclaimed all citizens as equal – although the reality was a far cry from the rhetoric. Official government-led antisemitism remerged in 1953 under Soviet leader Joseph Stalin in the form of the Doctors Plot – an alleged conspiracy by a group of mostly Jewish doctors to murder leading Communist Party officials. The plot was thought to be a precursor to another major purge of the party, and was halted only by Stalin’s death. Once again, as a backdrop to today’s ugly war, history is repeating itself. “We’re seeing rising antisemitism while Russia is going back to a new kind of Soviet Union, and step by step the iron curtain is coming down again. This is why I believe the best option for Russian Jews is to leave,” Goldschmidt said. Jews are increasingly being blamed for Russia’s difficulties in the war – Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky is Jewish, of course. The Russian government and state-controlled media, as well as many on the far right, routinely repeat antisemitic tropes and conspiracy theories. Foreign secretary Sergei Lavrov in May trotted out the unfounded claim that Hitler was part-Jewish, in a crude attempt to portray Zelensky as a Nazi. Goldschmidt served as Moscow’s chief rabbi for over 30 years until he resigned in July, prompted by fears that the city’s Jewish community would be endangered if he stayed, after he refused to voice support to the war and gave assistance to Ukrainian refugees. He had already left Russia in March, two weeks after the invasion of Ukraine began. “Pressure was put on community leaders to support the war, and I refused to do so. I resigned because to continue as chief rabbi of Moscow would be a problem for the community because of the repressive measures taken against dissidents,” he said. Goldschmidt first urged Russian Jews to flee the country in October after the assistant secretary of Russia’s Security Council, Aleksey Pavlov, proclaimed the Jewish orthodox Chabad movement to be a supremacist cult. Chabad is the largest Jewish sect in the former Soviet Union. “Now we are under pressure, wondering if what was published in the newspaper — this interview with a top security official — represents the start of an official wave of antisemitism. I think that would be the end of a Jewish presence in Russia. Official antisemitism would drive every Russian Jew out of the country,” Baruch Gorin, a spokesperson for the Russian Jewish community, said at the time. Since July, Russia has been engaged in a legal battle with Israel over its attempts to close down the Russian branch of the Jewish Agency, an Israeli quasi-governmental organisation that promotes Jewish immigration to Israel and organises Jewish cultural and educational activities in Russia. Moscow’s efforts call to mind earlier crackdowns on the organisation and on Jewish communal life during Soviet times. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Goldschmidt estimates that between a quarter and a third of Russia's Jews have left the country or are planning to do so. More than 43,000 Russians and 15,000 Ukrainians emigrated to Israel last year. In all, some 200,000 Russians have left the country since the war began, many of them as a result of Putin’s mobilisation drive in September. Jews comprise a disproportionate number of Russia’s middle class and the exodus marks a considerable brain drain for Russia, with a large contingent of business and cultural leaders, intellectuals and creatives fleeing the country.  I was invited to give a presentation at a Christian-Jewish church service with a theme of persecution and immigration, as part of this year’s North Cornwall Book Festival. The recent horror of refugees trying to flee Afghanistan in the wake of the Taliban victory, and the plight of migrants making perilous sea crossings in an attempt to reach Europe or the UK, have once again brought these issues to the fore. My own family lived through the pogroms, a series of anti-Semitic riots that took place in the Russian Empire, which in many ways served as a precursor to the Holocaust. Today, we would probably call the pogroms a form of ‘state-sponsored terrorism’ against Jews – supported and incited by the government, if not actually perpetrated by it. They began in 1881, when Jews took the blame for the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, and continued in waves for the next 40 years, peaking in 1905 before coming to a head during the Russian Civil War – a chaotic and intensely violent period that lasted for about four years following the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. During the civil war, the area where my family lived – near Kiev, in present day Ukraine – became a battleground with numerous armies criss-crossing the land – Communists, Nationalists, Anarchists, anti-Bolsheviks, peasant militias – all of them anti-Semitic to a greater or lesser degree. The White Army in particular, which was loyal to the Tsar – and backed by the West – introduced methods of mass murder of Jews that were later taken and pushed to their limit by the Nazis twenty or so years later. Many White Army soldiers later went on to join the Ukrainian militias that collaborated with the Nazis to destroy all Jewish life in Ukraine in the early 1940s. As well as the violence during the civil war, there was hunger. Food had become scarce during World War l, inflation soared making what little there was unaffordable, and the Bolsheviks requisitioned grain from the countryside (including from my great-great grandfather, who was a grain trader), to feed the workers in the towns. Not only did they take the grain, but also the seed, leaving the peasants with nothing to grow crops with the following year. The population was left to starve. My grandmother Pearl was around 17 years old at the start of the civil war, and an orphan. She lived with her grandparents, siblings and cousins and took it upon herself to become the family breadwinner, undertaking terrifying and dangerous journeys by train to markets across the region to buy, sell and barter what she could to keep her family alive. Eventually she even became a black-market gold dealer – taking any gold items belonging members of her local community on a murderous journey half way across Ukraine to exchange them for hard currency, which she brought back to the villagers so they could use it to buy food. Had she been caught, either with the gold or hard currency, she would have been shot. After more than three years of this perilous life that she hated with a passion, and following a particularly arduous trading trip when she was caught in a snowstorm and almost froze to death, she could take it no more. She decided she must try to get herself and her family out of the country. Six months later, in 1924, Pearl managed to emigrate to Winnipeg, Canada to join some other members of her extended family who had already made it out of Russia. She travelled alone, and with nothing. Once in Canada she did what so many immigrants do. She found a job and worked hard, scrimping, saving, and borrowing to raise enough money to bring the rest of her family over to join her the following year. Today my family is spread across Canada, from Vancouver to Toronto, and in America from California to New York, as well as in Germany, Israel and the UK, where they became, among other things, teachers and lawyers, journalists and doctors, Rabbis and social workers, all adding in their own unique ways to the prosperity and cultural life, as well as the wonderful diversity, of the places they now call home. Photo: Pearl (left) with her sisters Sarah (centre) and Rachel, circa 1920 As another lockdown Passover begins, I’ve been reflecting on this Passover story that dates back nearly a century, to the late 1920s. My great-grandmother’s cousin Babtsy arrived in Winnipeg, Canada, with her husband Moishe and four children at the end of their long journey from Kiev, which at that time had recently become part of Soviet Ukraine. Babtsy and Moishe had survived a terrible pogrom in their home town of Khodorkov in 1919. The town’s Jews had been rounded up and herded to a sugar beet factory beside a lake, then forced to keep going deeper into the lake until they drowned or froze to death. Babtsy and her family had hidden in a basement and, when it was safe to emerge, they found houses smouldering around them and the lakeside littered with pale corpses. Barely stopping to grab a handful of belongings, they fled to the railway station and took the first train to Kiev, where they remained for several years, living with Moishe’s parents. Owing to a mixture of errors, misunderstandings and delays, it took three and a half years from the time they first lodged their application to emigrate to Canada to their eventual arrival in Winnipeg. Remarkably, our family has around 50 pages of documentation relating to this process, consisting of letters between the Jewish Immigrant Aid Society Western Division in Winnipeg, its head office in Montreal, and the Canadian Department of Immigration and Colonization in Ottawa. I have written about this in a previous article, which you can read here. Once Babtsy, Moishe and their children finally arrived at the Canadian Pacific Railway Station in Winnipeg, they asked the station master to call the phone number of Babtsy’s cousin Faiga. Faiga had been the first member of our family to leave the Russian Empire for Winnipeg back in 1907 with her husband, Dudi Rusen, and one of her brothers. Dudi was an ambitious young man. Once in Winnipeg he bought a pushcart and based himself on a street corner to sell fruit and vegetables. He worked hard and after a while had raised enough money to buy a truck, then within a few years he was running his own wholesale produce company. Faiga and Babtsy had not seen one another for more than 20 years. Faiga and Dudi, with their children and grandchildren, were in the middle of a Passover Seder when the station master rang on that spring evening. Dudi answered the phone and told him to put the newly arrived family in a taxi and send them straight to his home at 107 Hallett Street. To great excitement, everyone budged up around the table to make space for the relatives from the Old Country so they could join the Seder, and celebrate this latest escape of Jews, to a new Promised Land, alongside the ancient exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. This Passover story is narrated in the following clip by Monty Hall, the host of TV’s Let’s Make a Deal. Monty was Faiga and Dudi Rusen’s grandson and was at their house that evening during Passover. In the video, Monty describes his tremendous excitement at reading my book, A Forgotten Land, and discovering that it was about his own family. Monty contacted me after he read the book and we had a long telephone conversation, during which he recounted this Passover story to me. After many years hosting Let’s Make a Deal, Monty Hall engaged in philanthropic work, helping to raise close to a billion dollars for charity. He features in both the Hollywood and Canadian Walk of Fame, and the Walk of Stars in Palm Springs, California, and was awarded the Order of Canada in 1988. He died on 30 September 2017 at the age of 96.  One of the most original and unusual books I’ve read in a long time is The Slaughterman’s Daughter by Yaniv Iczkovits, a recent release, translated from the Hebrew, from the always impressive MacLehose Press – a UK publisher that specialises in works in translation. Set in the Pale of Settlement of Imperial Russia at the end of the 1800s, it tells the story of Fanny Keismann, the eponymous daughter of a kosher butcher, who goes in search of her brother-in-law, Zvi-Meir, after he abandons her sister and their two children. Fanny’s journey to Minsk – now the capital of Belarus and recently in the news for mass protests against its tinpot dictator Alexander Lukashenko who refuses to give up power – is fraught with danger. Fanny’s talent with a butcher’s knife stands her in good stead to quell her foes, but it also sets in train a fantastical series of events that spiral out of control and, unsurprisingly, get her into trouble with the law. Like the stories of Sholem Aleichem, this book and its cast of motley characters evokes a nostalgia for the shtetls of Belarus, Ukraine and elsewhere in the region before the Russian Revolution, and a way of life that was already beginning to unravel when this novel was set. Hundreds of thousands of Jews had begun to emigrate to the west (mostly the United States) in search of an escape from discrimination, anti-Semitic violence and economic hardship from the 1880s onwards. Later, of course, during the Nazi occupation of 1941-44, the shtetls were destroyed altogether, their inhabitants murdered or, in the case of a lucky few, forced to flee eastwards in a bid for survival. It is impossible not to feel a deep regret for the disappearance of these vibrant communities where our ancestors lived for generations, settlements that were extinguished so brutally. I for one am fascinated by stories and images of the lost Jewish world of Eastern Europe. But the shtetls were home to a way of life that was tough and unenviable, as this novel demonstrates. They were generally poor, miserable places, where, “The Jews have huddled so close to each other that they have not left themselves any space to breathe”. And where Jew and Goy often distrust one another absolutely. For most of us with origins in the kinds of places that Iczkovits writes about, when we think of this period of history what we remember are the pogroms – the brutal anti-Semitic violence that broke out periodically in Russia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This book, filled with black humour and deep affection, but also gritty realism, provides a wonderful illustration that there was much more to this time and place. The author describes a way of life where, outdoors, “The market is a-bustle with the clamour of man and beast, wooden houses quaking on either side of the parched street. The cattle are on edge and the geese stretch their necks, ready to snap at anyone who might come near them. An east wind regurgitates a stench of foul breath. The townsfolk add weight to their words with gestures and gesticulations. Deals are struck: one earns, another pays, while envy and resentment thrive on the seething tension. Such is the way of the world.” Meanwhile, indoors, mothers share a bed with their multiple children and face continual curses and criticism from their in-laws in the next room, who treat them like servants. Yaniv Iczkovits is an Israeli born of Holocaust survivors. “What I wanted to do was to bring these forgotten memories of this lost world into 21st century Israel, and to present the richness of a culture that is now gone, but is still a major part of who we were and what we are,” he says.  I finally had the opportunity during lockdown to watch a documentary that I’d been wanting to see for a long time. My Dear Children, a 2018 film by director and co-producer LeeAnn Dance, tells the personal and heart-rending tale of a family separated by thousands of miles as a result of pogroms during the Russian Civil War. Central to the story is Feiga Shamis, a mother who strives to protect her 12 children from the turbulence and violence around them. The pogroms of 1917-1921 were far more terrible than any of the anti-Semitic violence that had gone before, with a death toll estimated anywhere between 50,000 and 250,000, and up to 1.6 million injured, attacked, raped, robbed, or made homeless in the largest outbreak of anti-Jewish violence before the Holocaust. The number of individual pogroms is estimated at more than 1,200. Feiga’s 16-year-old son was killed during one of these, while her husband – like my own great-grandfather – died during the typhoid epidemic of 1918-19. “We overheard them saying they should kill all the Jewish children so the Jews would die out,” Feiga wrote. It was time to plot her escape. With her older children married off or sent to the US, she fled to Warsaw with the four youngest, where she placed two of her children – eight-year-old Mannie and 10-year-old Rose – in an orphanage, a fairly common practice at the time. “I thought the children would be safer in the orphanage,” she wrote, “so I took them there.” From Warsaw, the two children were selected as part of a rescue effort by Isaac Ochberg, a Jewish South African philanthropist, who managed to bring to safety nearly 200 Jewish orphans from his former homeland. At great personal risk, he travelled around Eastern Europe collecting children from orphanages and bringing them to Warsaw—to the orphanage where Feiga had placed her children. Only later did Ochberg learn the children’s mother was alive. When Feiga learned of the plan, she faced a heartbreaking decision—keep the children with her, or let them go, to a place half a world away where she would probably never see them again, but where she was assured that they faced a better future. She chose to let them go. My Dear Children is based on a long letter that Feiga wrote to Rose and Mannie after she had emigrated to Palestine in 1937 to live with one of her older daughters. She gave it to Mannie on the one occasion they met after his and Rose’s departure for South Africa. As a young soldier in the South African army, Mannie was posted to Egypt, from where he took a week’s leave to visit his mother. Tragically Mannie cut short his week-long visit to just a single day, with he and his mother unable to connect to one another. Mannie never read his mother’s letter, suppressing a past that was too painful to contemplate. For the rest of his life, Mannie would agonise over why his mother had sent him away, and neither he nor his sister Rose would ever talk about their childhood back in Russia. It wasn’t until after Mannie’s death that his widow had the letter translated from Yiddish into English, printed as a small book, and distributed among members of the family. The scenes that Feiga witnessed during the Civil War and her experiences during that time resonate deeply with the recollections of my grandmother, documented in my book A Forgotten Land. In particular, Feiga wrote about becoming a black-market vodka trader, bartering vodka for food to keep her family alive. My grandmother too was a black-market trader at this time, dealing in food, and later gold, as the sole breadwinner for her grandparents, siblings and cousins. It is clear from her writing that Feiga remained racked with guilt and suffering over her decision to allow her children to leave for South Africa, and she wrote the letter as a justification and explanation for what she had done. In 2016, Mannie’s daughter Judy and granddaughter Tess set out on a trip to Poland and what is now Ukraine, hoping to find answers as to why Mannie refused to talk about his past and what drove Feiga to the choice she made. They found a landscape virtually erased of its Jewish past. “The Holocaust did not happen in a vacuum. The pogroms of 1917-1921 should be seen as a precursor to the greater tragedy just 20 years later. My Dear Children shows the consequences of unchecked, or worse – officially sanctioned – anti-Semitism, and given the increasing incidents of anti-Semitism today, this story remains relevant today. Feiga’s story is not unique. Nearly 80% of the world’s Jewry can trace their roots to Eastern Europe, thus Jews around the world share Feiga’s story. Many likely have no idea they do so.” LeeAnn Dance said in an interview for the Washington Jewish Film Festival in 2018. For more information about My Dear Children, click here www.mydearchildrendoc.com  My second and final post based on the publication A Journey through the Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter looks at issues of assimilation and emigration. The Journey is a fascinating document published last year by a private multinational initiative called Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter aimed at strengthening mutual comprehension and solidarity between Ukrainians and Jews. Jewish assimilation in the Russian Empire wasn’t necessarily a question of choice. The government of Tsar Nicholas I enacted measures to refashion and forcibly assimilate the Jewish population. In 1827, it ordered a quota system of compulsory conscription of Jewish males aged 12 to 25 (for Christians it was 18 to 35) to the Tsarist army and made the leadership of each Jewish community responsible for providing recruits. The selection process was often arbitrary and influenced by bribery, turning Jews against their communal leaders. By 1852–55, so-called happers were tasked with kidnapping Jewish boys, sometimes as young as eight, in order to meet the government’s quotas. As described in my book, A Forgotten Land, the happers spread fear across the Pale of Settlement. Once conscripted, the young Jewish recruits were pressured to convert to Russian Orthodoxy, with the result that around one-third were baptised. The drafting of children lasted until 1856. Other assimilationist measures included the establishment of state-sponsored secular Russian-language schools for Jewish children and rabbinic seminaries to train ‘Crown Rabbis’ who were expected to modernise the Jews. An 1836 decree closed all but two Hebrew presses and enacted strict censorship of Hebrew printing. In 1844 the kahal system of Jewish autonomous administration was abolished. Decrees were also passed on how Jews should dress and the economic activities in which they were allowed to engage. The Jewish Enlightenment – an intellectual movement across central and eastern Europe promoting the integration of Jews into surrounding societies – helped to further the aims of the tsarist government. Activists known as maskilim were enlisted to censor Jewish religious books, as these were considered to promote fanaticism and be an obstacle to Russification. A series of laws and decrees improved the situation of the Jews under Tsar Alexander II (1855-81). Conscription requirements became less severe, while some Jews were allowed to reside outside the Pale and to vote. Political and social reforms enabled the first generation of Jewish journalists, doctors, and lawyers to obtain degrees at the state-sanctioned rabbinic seminaries and universities, going on to form the core of a modernised Jewish intelligentsia. Journalists and writers, often from the ranks of the maskilim, began to publish Russia’s first Hebrew, Yiddish, and Russian-language Jewish newspapers. Modernist synagogues were established. But state-sponsored discrimination against Jews continued, as did anti-Semitic articles in the Russian press and the expulsion of Jews deemed to be residing in Kiev illegally. The assassination of Tsar Alexander II in 1881 triggered a new round of repression, with Jews banned from certain professions and geographical areas, and political and educational rights restricted. Only Jews who converted to Orthodox Christianity were exempt from the measures. By the late 1800s, a small group of prosperous Jewish traders had emerged, but the vast majority of Jews lived a modest existence that often bordered on poverty. According to the Jewish Colonization Society, in 1898 the poor comprised 17-20% of the Jewish population in several provinces of present-day Ukraine. But worse than the grinding poverty and discrimination were the pogroms. Derived from the Russian verb громить (gromit’), meaning to destroy, pogroms were waves of violent attacks on Jews that took place across the Pale primarily in 1881-82, 1903-06, and 1918-21. Alexander II’s assassination triggered mobs of peasants and first-generation urban dwellers to attack Jewish residences and stores. Of 259 recorded pogroms, 219 took place in villages, four in Jewish agricultural colonies, and 36 in cities and small towns. Altogether 35 Jews were killed in 1881–82, with another 10 in Nizhny Novgorod in 1884. Many more were injured and there was considerable material damage. A second wave of pogroms began in 1903 with an outbreak of anti-Semitic violence in Kishinev, in which the authorities failed to intervene until the third day. Further pogroms followed Tsar Nicholas II’s manifesto of 1905 that pledged political freedoms and elections to the Duma. The mass violence was orchestrated with support from the police and the army and carried out by the ‘Black Hundreds’ – monarchist, Russian Orthodox, nationalist, anti-revolutionary militants. Around 650 pogroms took place in 28 provinces, killing more than 3,100 Jews including around 800 in Odessa alone. Jews attempted to resist pogroms in many areas by organising self-defence groups. Many were community-organised, but the Jewish Labour party or Bund also began mobilising self-defence units in the early 20th century. The 1881–82 pogroms set in motion new political and ideological movements, and led to large-scale emigration. For many Jewish intellectuals, the goal of integration and transformation of communities through education and Russification was now discredited. Some perceived socialism, with its promise of equality, as the solution; others promoted emigration to America or Palestine. By the end of the nineteenth century, both Jews and Ukrainians began to emigrate in large numbers, mostly to North America. In 1882 Leon Pinsker, a physician from Odessa who had earlier promoted the integration of Jews into broader Russian society, published an influential pamphlet titled Autoemancipation, in which he advocated that Jews establish a state of their own. He proceeded to found the Hibbat Zion movement, which paved the way for the Zionism. In 1882–84 some 60 Jews from Kharkov moved to Palestine, the first mass resettlement of Jews in Israel. From 1897 Zionist circles were established in several Ukrainian cities, making the region a centre of organised Zionism. The Tsarist government was initially indifferent towards the Zionists, but eventually banned them. According to the 1897 census, 2.6 million Jews lived on the territory of present-day Ukraine. Kiev and some other provinces had a Jewish population of around 12-13%, while in Odessa, Jews made up almost 30% of the population. Of the Jewish population, more than 40% were engaged in trade, 20% were artisans and 5% civil servants and members of ‘free professions’, such as doctors and lawyers. Just 3-4% were engaged in agriculture, in contrast to the vast majority of the Ukrainian population. Given these figures, the scale of emigration was immense. More than two million Jews migrated to North America from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1914, mainly from lands that make up present-day Ukraine. Of these, about 1.6 million came from the Russian Empire (including Poland), and 380,000 from provinces of western Ukraine that were at the time part of Austria-Hungary (mainly Galicia). Another 400,000 Eastern European Jews migrated to other destinations, including Western Europe, Palestine, Latin America, and southern Africa. Jews comprised an estimated 50 to 70 percent of all immigrants to the United States from the Russian Empire between 1881 and 1910. About 10,000 Jews had arrived in Canada by the turn of the century, rising to almost 100,000 between 1900 and 1914, settling mostly in Montreal, Toronto and Winnipeg, the hub of the Canadian Pacific Railway, where my own family settled. Click here to see the document on which this article is based https://ukrainianjewishencounter.org/media/UJE_book_Single_08_2019_Eng.pdf?fbclid=IwAR2D2QAuBtjsIqF1kHi4eRUlxBZT-UFPR3usj0741Cp3nnnouJT1icJGphM  I have both read and written a lot about the pogroms in Ukraine, which were at their peak a hundred years ago. Like Holocaust literature, the more one reads, the more one ceases to be shocked and horrified. I thought that reading about the pogroms would no longer have the searing impact on me that it once did, but I have found that a new book published this month still has the ability to sicken. The work, by Nokhem Shtif, was first published in Yiddish 1923, but now appears in English for the first time translated and annotated by Maurice Wolfthal as The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918-19: Prelude to the Holocaust. Shtif was editor-in-chief of the editorial committee for the collection and publication of documents on the Ukrainian pogroms, which was founded in Kiev in May 1919. Shtif focuses specifically on atrocities committed by the Volunteer Army, also known as the White Army, under General Anton Denikin, as opposed to the myriad other armies and militarised groups – banda as my grandmother called them – that were rampaging violently across Ukraine at the time. The number of Jews murdered in Ukraine in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution is estimated at anywhere between 50,000 and 200,000, with up to 1.6 million injured, attacked, raped, robbed, or made homeless in the largest outbreak of anti-Jewish violence before the Holocaust. The number of individual pogroms is estimated at more than 1,200. “The Jews were attacked by a number of different groups of perpetrators including Anton Denikin’s Russian Volunteer Army, Simon Petliura’s Army of the Ukrainian Republic, various peasant units, hoodlums, anarchists, and the Bolshevik Red Army. “These attacks stemmed from a number of grievances: accusations of supporting the enemy side, the chaos following the collapse of the old order, the aftermath of World War I and of the Russian Revolution, and a widespread anti-Semitism, after the dissolution of the Russian and Habsburg Empire.” So writes the Berlin-based historian Grzegorz Rossolinski-Liebe in his preface to the book. The relative lack of literature and research on these events provides some explanation for why the Ukrainian pogroms have garnered so much less attention than the Holocaust that followed some 20 years later. Of the research that does exist, much focuses on the nationalist leader Petliura, the subject of my December 2018 blog post. When it comes to Denikin, “the crimes committed by his army have not been forgotten but they were neither investigated as thoroughly as the massacres by the Petliura army nor did they arouse any major controversies, because none tried to systematically or deliberately deny them as the Ukrainian nationalists did in the case of Petliura’s soldiers”, Rossolinski-Liebe argues. But Denikin’s army was unique among the banda in that it murdered Jews in an orderly and methodical way, clearing out the Jewish population from the towns and villages it raided using many of the practices that would be adopted by the Nazis two decades later. The author’s aim is to demonstrate that the pogroms were an integral part of the Volunteer Army’s military campaign, much as the murder of the Jews was for the Nazi regime. The Volunteer Army was a force made up of former Tsarist officers that aimed to drive out the Bolshevik regime and restore every aspect of Russia to its pre-Revolutionary days. Their aims, as Shtif says were, “The land must be returned to the aristocracy. The labor movement must be crushed […] Jews will continue to be second-class citizens, oppressed and subservient.” Pogroms were a way of preventing Jews from gaining the equal human rights that the revolution had granted them. Shtif is convincing in his explanation of the causes of the pogroms: “For the reactionaries pogroms are a way to prevent Jews from obtaining equal rights, which the hated Revolution granted them. Pogroms are the first step towards reducing them to a state of slavery. That principle […] is at the root of the pogroms. In the eyes of reactionaries Jews are creatures without rights. And as soon as anyone dares to give them their rights, they are outraged and they burn to put the crown back on the head of perverted justice. In the eyes of reactionaries, of course, Jews have no rights.” In describing the events of the pogroms, I feel traumatised yet again knowing that my grandmother and her family lived through and survived such terrifying times. So much of what Shtif writes corroborates what my grandmother said about the pogroms, and the many different banda that perpetrated them. The towns my great-grandparents came from – Pavoloch and Makarov – both in Kiev province, receive several mentions in the book, each one sending shivers down my spine. “So horrendous are the accounts that they are difficult to grasp,” Shtif writes…. “There are no words…” It often feels in these troubling times of the early 21st century that swaths of the population in many parts of the world are returning to the extreme nationalism that pervaded a century ago. We seem to be revisiting that world of religious extremism, with murderous attacks on immigrant communities and a US president who vilifies those of other faiths and nationalities. We would be well served to learn lessons from the past and prevent the current polarisation of society from leading once again to the kind of mass violence that tore Ukraine apart a hundred years ago. The Pogroms in Ukraine, 1918-19: Prelude to the Holocaust is published by Open Book Publishers  I recently came across the story of the Ochberg orphans, nearly 200 Jewish children rescued in 1921 from the ravages of the Russian Civil War, pogroms and the subsequent typhus epidemic and famine. The rescuer was Isaac Ochberg, a Ukrainian Jew who had emigrated, penniless, to South Africa in 1895 and went on to become a successful entrepreneur. By 1920 he was one of South Africa’s richest men and leader of the Cape Town Jewish community. Horrified by the news of the pogroms, which together with war, disease and hunger left an estimated 300,000 Jewish children orphaned, Ochberg turned to the South African Jewish community for help in financing a rescue mission to bring Jewish children to South Africa for adoption. Ochberg left for eastern Europe in March 1921, travelling by road and rail through Ukraine, Lithuania and Poland in search of the neediest children, visiting synagogues where orphans had gathered and orphanages funded by Jewish foreign aid. This was no easy journey. Civil war was still raging in some areas, pitting against one another numerous marauding bands of soldiers – from Ukrainian Nationalists to Communists and Anti-Communists, Germans and Poles to Anarchists and local warlords – all of them anti-Semitic to a degree. The area was filled with people on the move – refugees, the hungry, the sick and the weak. As well as war and pogroms, typhus and famine had ravaged the population. By August 1921 he had assembled a group of 233 children in Warsaw, ready for the train journey to Danzig (Gdansk) and onward journey to London then Cape Town. Some of the group fell ill and were forced to stay behind. Others ran away, scared off by stories of Africa and its wild animals. The task of selecting the children must have been heart-breaking, given the number he had to leave behind. The South African government, under Prime Minister Jan Smuts, had matched the funding Ochberg managed to raise, but laid down certain conditions. Two hundred orphans could come, but no sick children, nor any with mental or physical disabilities. No child could be selected if there was a living parent, nor any child over the age of 16. Under no circumstances could families be broken up; if one member of a family did not qualify, the siblings had to remain behind. But Ochberg had no qualms about ignoring these rules. Siblings aged 16 or over became accompanying ‘nurses’, and several whose parents were still living, but had chosen to give up their children in the hope of offering them a better life, were included in the group. Some 165 children and 25 accompanying adults made the journey to South Africa, where they were divided equally between Jewish orphanages in Cape Town and Johannesburg and offered for adoption. A 2008 film made by South African film maker Jon Blair entitled Ochberg’s Orphans tells the children’s story, interspersed with harrowing images of the pogroms, and interviews with some of the last remaining orphans still alive at that time. “When we arrived we thought we were in Fairyland,” one recalled. And of Ochberg, the same old lady said, “We called him Daddy, because for most of us children he was the only daddy we ever knew”. The film includes footage shot by UK camera crews while the group spent two weeks at an orphanage in London before heading to Southampton to board the ship for Cape Town. The children briefly became minor celebrities, having captured the imagination of the British media. The story of the Ochberg orphans also features in a new film by US filmmaker LeeAnn Dance, My Dear Children. I have not managed to see the film yet, but it has been broadcast on TV across the US and at film showings at Jewish centres. I have been in touch with the filmmaker and look forward to seeing it at the first opportunity. The film centres on Judy Favish’s 2013 pilgrimage to trace her grandparents Feiga and Kalman Shamis’s route from their shtetl in Ukraine to Warsaw with their 12 children. Two of Feiga’s children, Mannie and Rose, joined the group that travelled from Warsaw to Cape Town with Isaac Ochberg. Feiga’s other children were dispersed – two were sent to New York, while five survived the pogroms only to die later in Nazi concentration camps, and one ended up in Palestine. Mannie was adopted from one of the Jewish orphanages in South Africa, but Rose refused to let herself be taken by another family, never giving up hope that her mother would come for her. But she never did. Feiga did maintain contact with her children, however. Years later she settled on a kibbutz and Mannie was able to visit her there while serving as a soldier in North Africa during World War II. She gave him two copies of a 40-page letter, handwritten in Yiddish, which contained the story of her life. Neither Mannie nor Rose could read or speak Yiddish, and although Mannie eventually had the letter translated, he couldn’t bear to read it. It wasn’t until after he died that one of his children had it properly translated and edited, and made into a small book, a copy of which she gave to each family member. Although both Mannie and Rose felt that their mother had abandoned them, for Feiga it was a case of doing what she could to ensure her children would survive. Little could she know that for those who escaped from Europe, her decision also spared them the horrors of the Holocaust twenty years later. More information about My Dear Children is available here: www.mydearchildrendoc.com/ The film of Ochberg's Orphans is available to view here:  This month marks the centenary of one of the worst pogroms in history, an attempt at genocide against the Jews of the town of Proskurov in present-day Ukraine. In February 1919, local Cossack leader Ataman Semosenko assumed command of the nationalist forces in the region and called for the elimination of the Jews in order to “save Ukraine”. As the town’s Jews, who numbered around 25,000, prepared to celebrate the Sabbath, hoards of Cossacks descended on the town and began attacking Jews in the streets and in their homes with knives, swords, bayonets and even hand grenades. The following are accounts from survivors: “They [the Cossacks] were divided into groups of five to 15 men and swarmed into the streets which were inhabited by Jews. Entering the homes, they drew their swords and began to cut the inhabitants without regard to sex or age… Jews were dragged out of cellars and lofts and murdered.” Entire families were slain. One survivor, a nurse by the name of Chaya Greenberg, later testified: “The young girls – repeatedly stabbed. The two-month old baby – hands lacerated. The five-year old – pierced by spears. The elderly man – thrown out of a window by his beard. The 13-year old – deaf because of his wounds. His brother – 11 wounds in his stomach, left for dead next to his slain mother. The paralysed son of a rabbi – murdered in his bed. The two young children – cast alive into a fire….I will never forget the reddened snow from sleds filled with the hacked bodies going to a common pit in the cemetery.” Some of the victims were forced to dig their own graves. Around 1,600 Jews are estimated to have been killed, although some put the death toll higher. Many more sustained terrible injuries and were crippled for life having had limbs severed. The Jewish hospital and makeshift medical stations were filled with the wounded as relatives and local peasants brought in the victims. Most were buried in mass graves. Some gentiles risked their lives to protect their fellow townsfolk, in a community that generally experienced good relations between those of different faiths. A doctor named Polozov helped many wounded Jewish children he found in the street. He hid more than 20 Jews in his own home. Priests were murdered as they attempted to halt the pogrom. The Proskurov pogrom was just one of hundreds that took place in Ukraine in 1919 during Russia’s chaotic and bloody civil war that followed the Bolshevik Revolution. The pogroms followed the withdrawal of German troops after World War I, when Communists, Ukrainian nationalists, the anti-Bolshevik White Army and numerous smaller factions vied for control, all of them engaging in anti-Semitic violence to a greater or lesser degree. The words of historian Orest Subtelny in his mammoth Ukraine: A History are worth repeating, “In 1919, total chaos engulfed Ukraine. Indeed, in the modern history of Europe no country experienced such complete anarchy, bitter civil strife, and total collapse of authority as did Ukraine at this time”. My own ancestral village of Pavoloch, where like Proskurov relations between Jews and the rest of the community were generally amicable, suffered wave after wave of attack by different groups of fighters, who my grandmother referred to collectively as ‘banda’. The most vicious was the White Army under General Anton Denikin. The following is an extract from A Forgotten Land describing just one of many, many horrors that my family suffered in Pavoloch in 1919: “The Whites weren’t like the anarchists who burst in and began smashing the furniture to pieces. They had brains and intuition that they used to figure out just where their victims might be hiding money or jewellery or hoarding food. The soldiers sniffed around like dogs, tapping at walls and floor boards, listening for a hollow echo that might indicate a hiding place. “‘Money! Give us your money, old man!’ the first giant demanded in Russian, prodding Zayde [Grandpa] with his bayonet. “Zayde’s carefully learnt Russian seemed to desert him and he mumbled something incomprehensible, his eyes fixed on the scuffed leather boots of his interrogator. “While his companions continued to search the house, kicking down the door to the warehouse, the leader of the group dealt my grandfather a swift blow with his rifle butt and watched poor Zayde crumple to the floor like a rag doll. Then he kicked him in the stomach with his huge leather boots until Zayde curled into a ball on the hard kitchen floor as pitiful as a tiny child. Again and again he beat him with his gun and kicked him. “By that time the other four soldiers had returned. Zayde wasn’t a big man so it didn’t take them long to hustle him onto the table, pull his scuffed leather belt from around his waist and force his head into the noose they made with it. Then they hanged him from the hook on the kitchen ceiling that we used for drying meat.” My great-great grandfather survived the ordeal, but only because the belt that was used to hang him snapped in two, dropping him to the floor with a great thump. But he was never the same again. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed