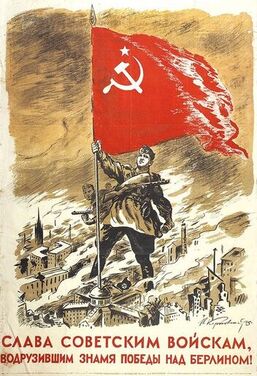

Victory Day, on 9 May, is the most solemn and serious of national celebrations in Russia. On this date thirty years ago, I was in the southern Russian city of Voronezh. It was a beautiful, sunny day, the warmest of the year so far after a long, bleak winter. The main street was closed to traffic and it seemed the whole population of the city was outdoors. But the glorious holiday weather didn’t prompt people to shed layers of clothing and relax with picnics and drinks in the city’s parks as they might have elsewhere. Instead, families walked, silent and sombre, towards the war memorial to lay flowers, three or four generations together. The older men wore rows of medals with multi-coloured ribbons attached to their jackets. Many were dressed in military uniform. The women were togged up in their Sunday best. Children were primped and preened with oversize bows for the girls and buckles and braces for the boys. Although the holiday celebrated the victory of Soviet forces in the Great Patriotic War – as World War II is known – there was no sense of jubilation. The Soviet Union paid a heavy price for the victory and the war took a terrible toll. An estimated 27 million Soviet citizens died during the war. Every family lost a son, a brother, a father, an uncle or a cousin. The pomp and ceremony of today’s Victory Day parade in Moscow add some glitz and glamour that didn’t exist in the immediate post-Soviet era. And of course, the war in Ukraine adds poignance to the occasion. It was no surprise that Vladimir Putin in his Victory Day speech linked the current conflict with the triumph over Nazi Germany. Time and again, he has drawn parallels between the two wars, starting with his bizarre notion of the need for Russia to rid Ukraine of Nazis. Given the Jewish origins of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky, who himself lost family members in the Holocaust, the Nazi tag has struggled to stick. But Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov’s recent comparison of Zelensky with Adolf Hitler, in an attempt to legitimise Russia’s goal of ‘denazifying’ Ukraine, took the analogy up a notch. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst anti-Semites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood – statements that typify the distortion of history that underpin Russia’s war with Ukraine. The question of Hitler’s Jewish identity is nothing new – and remains unproven. The issue centres on Hitler’s father, born in Graz, Austria, in 1837 to an unmarried mother. Speculation over who the child’s father was has continued for decades, fuelled by the fact that following the German annexation of Austria in 1938, Hitler ordered the records of his grandmother’s community to be destroyed. A memoir by Hans Frank, head of Poland’s Nazi government during the war, claimed that the son of Hitler’s half-brother tried to blackmail the Nazi dictator, threatening to expose his Jewish roots. Following worldwide outrage over Lavrov’s comments, and in particular heated condemnation from Israel, the Russian president was forced to issue a rare apology to his Israeli counterpart, Naftali Bennett, rather than risk alienating a country that has been more supportive than most. Israel has been an ally of Russia since the end of the Soviet Union – based in part on both countries’ military interests in Syria and the substantial Russian-Jewish population in Israel – and has faced criticism for failing to join Western sanctions. Israeli foreign minister Yair Lapid said Lavrov’s comments “crossed a line” and condemned his claims as inexcusable and historically erroneous, while Dani Dayan, head of Israel's Holocaust Remembrance Centre Yad Vashem, denounced them as “absurd, delusional, dangerous and deserving of condemnation”. Russia’s foreign ministry hit back, accusing the Israeli government of supporting a neo-Nazi regime in Kyiv. Only time will tell if the war of words leads to firmer Israeli support for Ukraine. Russian TV host Vladimir Solovyov last week pushed the Nazi narrative further, clarifying a new definition of Nazism to explain the ‘denazification’ of Ukraine. “Nazism doesn’t necessarily mean anti-Semitism, as the Americans keep concocting. It can be anti-Slavic, anti-Russian,” he said. To keep its phoney narrative alive, Russia will keep churning out the rhetoric on Nazism in the hope that if it repeats it often enough and loudly enough, more people will believe it. But the longer Putin’s Russia continues murdering Ukrainian citizens and bombarding Ukrainian cities, the more it resembles Hitler’s Nazi regime.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed