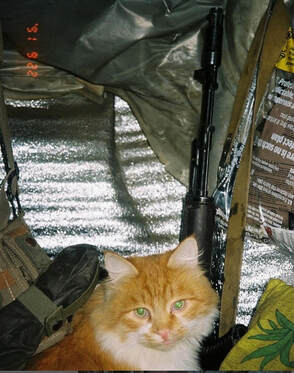

At least 95 Ukrainians known for their work in the creative industries have been killed since Russia’s full-scale invasion began nearly two years ago, according to the writers’ association PEN Ukraine. The organisation tracks losses among writers, publishers, musicians, artists, photographers, actors, filmmakers, and other creative professionals whose stories appear in the information field. It is likely that many more artists have been killed in the war than appear on PEN’s list. On 7 January the poet Maksym Kryvtsov was killed by artillery fire in Kupiansk, near Kharkiv, one of the key fronts in Moscow’s winter offensive. His loyal companion, a ginger cat, was killed with him. Kryvtsov, aged 33, had been hailed as one of the brightest hopes of Ukraine’s young, creative generation. Kryvtsov was an active participant in the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity – better known in the West as Euromaidan – and joined Ukraine’s armed forces as a volunteer in 2014, when the war against Russian separatists in the Donbas region began. He was later involved in organisations helping to rehabilitate fellow veterans and help them reintegrate into society, and also worked at a children’s camp. He was, by all accounts, far from the stereotypical image of a fighter. Kryvtsov returned to army in February 2022 when Russian forces invaded Ukraine. Comrades knew him by his call sign Dali – a reference to the curling moustache he grew in imitation of the Spanish artist Salvador Dali. “I think the war is a kind of micellar water that washes cosmetics off: from a face, streets, plans and behaviours. It’s like a hoe cutting through sagebrush, leaving a bitter aftertaste of irreversibility. In war, you become your true self, no need to play a role. You are simply a human, one of billions who ever lived on the Earth, sharing the commonality of breath. There’s no time for love at war. It lies abandoned next to a trash pile and disappears like a grandfather in a fog, lost somewhere behind this summer’s unharvested sunflower fields of a heart,” Kryvtsov said in a 2023 interview with Ukrainian publishing and literary organisation Chytomo as part of its Words and Bullets project with PEN Ukraine. Even through the chaos of war, Kryvtsov continued to write poetry. Many of his poems reflect on the harsh reality of war and the contrast between war and ordinary, civilian life. His first poetry collection Вірші з бійниці (Poems from the Embrasure) was hailed by PEN Ukraine as one of the best books of 2023. Within days of his death, the book’s entire print run had sold out and the reprint had racked up thousands of preorders. Profits from the book will be split between Kryvtsov’s family and projects to bring books to the armed forces. Hundreds of people gathered at St Michael’s monastery in Kyiv to attend a ceremony to honour Kryvtsov, ahead of a funeral in his hometown of Rivne. Some carried copies of his book, others a bouquet of violets, a reference to Kryvtsov’s final poem, posted on Facebook the day before he died (see below). The second part of the memorial service was held in Kyiv’s central Independence Square, the scene of the Euromaidan revolution in which Kryvtsov had participated. Mourners took turns stepping up to a microphone to share their memories of Kryvtsov and his poetry. He “left behind a colossal height of poetry,” said Olena Herasymiuk, a poet, volunteer and combat medic, who was a close friend of Kryvtsov. “He left us not just his poems and testimonies of the era but his most powerful weapon, unique and innate. It’s the kind of weapon that hits not a territory or an enemy but strikes at the human mind and soul.” (quote from the Associated Press) In an outpouring of grief on social media following Kryvtsov’s death, many drew parallels with Ukrainian cultural figures killed during the Soviet Union’s repression of writers and artists in the 1920s and 30s. Among these is the mighty figure of Isaac Babel, whose most famous collection of short stories Red Cavalry was written a century ago, inspired by Babel’s experiences as a war reporter in the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. I have recently been rereading the Red Cavalry stories and had intended my latest article to be about the historical parallels between Babel’s commentaries on war and contemporary war writers in Ukraine. That will have to wait for next time. Instead, I leave you with the prophetic poem Maksym Kryvtsov wrote the day before he died, and an extract from his poem about his ginger cat, posted on Instagram a few days earlier. My head rolls from tree to tree like tumbleweed or a ball from my severed arms violets will sprout in the spring my legs will be torn apart by dogs and cats my blood will paint the world a new red a Pantone human blood red my bones will sink into the earth and form a carcass my shattered gun will rust my poor mate my things and fatigues will find new owners I wish it were spring to finally bloom as a violet My Ginger Tabby When he falls asleep slowly stretches his front legs he dreams of summer dreams of an unscathed brick house dreams of chickens running around the yard dreams of children who treat him to meat pies my helmet slips out of my hands falls on the mud the cat wakes up squints his eyes looks around carefully: yes, they’re his people: and falls asleep again. Taken from Wikipedia, translation credited to Christine Chraibi

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed