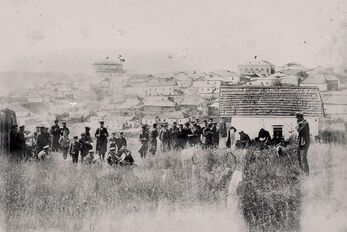

Ukraine doesn’t rank high on the holiday bucket list for most of us right now. But thousands of Hassidic Jews have ignored warnings about travelling to a war zone and flocked to the small town of Uman, some three hours south of Kyiv, for an annual new year pilgrimage. They came to worship at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov who was buried in Uman in 1810. Not all are religious Jews, for according to tradition, the rabbi promised to intercede on behalf of anybody praying at his grave on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. This year around 35,000 pilgrims arrived in Uman (up from the 23,000 who visited last year) in spite of warnings from the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities not to travel because of the risk of Russian air attacks and insufficient bomb shelters for the influx of visitors. Some brought young children with them, believing that a child who visits the grave site before the age of seven will grow up to be without sin. A small number of pilgrims have even been known to bring newborn babies to be circumcised in Uman, in spite of a lack of medical facilities for the procedure in Ukraine. Visitor numbers are only slightly down on the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, even though Uman has been targeted on several occasions. In April more than 20 missiles struck the town killing 24 people including several children in a residential district. It last came under Russian missile attack in June. The front line lies around 200 miles to the south. “It is very dangerous. People need to know that they are putting themselves at risk. Too much Jewish blood has already been spilled in Europe. How can you take such a risk?” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this month. With Ukrainian airspace closed, the journey to Uman is long, costly and uncomfortable, involving a flight to Poland, trains, minivan taxis and an inevitable long wait at the border. But the pilgrims remain undeterred in spite of the danger, expense and logistics of holidaying in a war zone. Some are firm in the belief that their Rabbi will protect them from beyond the grave; others just come to party and have a good time. Most come from Israel and spend up to a week in Uman around Rosh Hashanah. Although women are allowed on the pilgrimage, the vast majority of the visitors are men. The annual Jewish gathering has become the town’s major source of income, with pilgrims charged a $200 fee to visit. In recent years, the rabbi’s grave has been renovated with funds donated by Jewish tycoons from around the world. Hotels and hostels have popped up and locals have carried out house renovations to provide accommodation priced at hundreds of dollars a night. Those who can’t afford the exorbitant room prices pitch tents in courtyards or vacant lots. A whole hospitality industry has built up around the pilgrims, offering kosher food and drink at vastly inflated prices, using Hebrew signage and accepting payment in dollars or Israeli shekels. Most of the business owners are Israelis. Dozens of Israeli families moved to Uman in the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The annual influx of bearded, black-robed, skull-capped men makes quite an impact in this quiet town. While the visitors provide Uman with much-needed cash, relations between the pilgrims and the townsfolk are not always harmonious. Locals complain about the loud music, drunkenness, fighting and excessive litter. They resent the police cordons and checkpoints that prevent them from going about their daily business; and they question how the authorities are spending the money collected from the pilgrims, citing widespread corruption. Imagine a massive rave – albeit a religious one – taking over the streets of a small, unexceptional town and you start to get the picture. The Hassidic music blasting from speakers in the streets is imbued with a techno twist. Alcohol and drugs are much in evidence, as is prostitution. It’s hard to put a number on the percentage who come to celebrate and party, not just to pray. There’s a heavy security presence, even in peacetime, but it was stepped up this year in light of the added dangers of war. Police numbers have increased since 2010, when a young Israeli was stabbed in a brawl and ten pilgrims were deported after violent clashes broke out. Violence in Uman is nothing new. In 1941, under German occupation, the Nazis murdered 17,000 Jews here and destroyed the Jewish cemetery, including the grave of Rabbi Nachman, which was later located and moved before the area was redeveloped for housing. The original burial site was close to a mass grave for victims of another Jewish massacre, one that took place in 1768 as part of the Haidamak uprisings. The Uman pilgrimage began shortly after the rabbi’s death in the early 19th century and attracted hundreds of Hassidic Jews from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland until the Russian Revolution of 1917 closed the borders. The photo below dates from this period. In spite of the Communist regime’s clampdown on religious practice, a trickle of pilgrims continued to visit the grave site, including some Soviet Jews who made the journey in secret and were exiled to Siberia as a consequence. From the 1960s, small numbers of American and Israeli Jews travelled to Uman either legally or clandestinely. In the late 1980s, travel to the Soviet Union became easier and the number of pilgrims began to grow. Around 2,000 made the journey to Uman in 1990, rising to 25,000 by 2018.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed