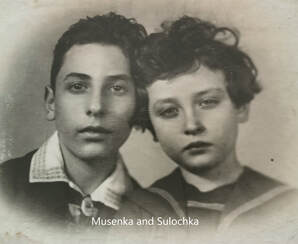

Soviet Jews that survived World War II by fleeing eastwards found a tough life waiting for them on their return home to towns and cities that had been occupied by the Nazis. I wrote recently about the experiences of several Jewish families as refugees in Central Asia during the war, including my great-grandfather’s sister, Miriam (Mira) – you can read that article here. Mira’s granddaughter Irina (Ira), who was born in Kiev after the war and lived there until the 1990s, has shared with me her family stories of life back in that city after the return from Central Asia. The family had lived before the war in the centre of Kiev, at 37 Pushkinskaya Street in a communal apartment – one room for each family, with shared cooking and washing facilities, as was typical of Soviet life during the era of Stalin and Khrushchev. Sometimes a family occupied just a section of a room, partitioned off with a curtain. On their return from Central Asia after the Nazi retreat in late 1943, Mira and her daughter Sulamia (Sulochka) – Ira’s grandmother and mother – made their way from the station on foot – no public transport was running – through the ruins of the devastated city, to find out what had become of their home. They found the four walls still standing, but nothing more. The building was restored after the war and exists to this day. “Whenever I go back to Kiev, I always wander around the courtyard and look up at the balcony, as if I’m looking for my mother as a little girl,” Ira says. A quick Google search shows an attractive four-story building on a tree-lined street, next door to a “hip Israeli eatery” called Pita Kyiv and just down the road from the Estonian embassy. As Ira’s mother and grandmother stood weeping before their ruined home, a figure approached them – a woman they had been acquainted with before the war. Knowing what had happened to the Jews of Kiev at the end of September 1941, when 34,000 were shot at the ravine of Babi Yar on the edge of the city, the woman took pity on Mira and Sulochka. She led them back to her basement flat on Saksaganskaya Street, a mile or so away, and invited them to stay. There Mira recognised many of her own possessions and those of her neighbours, stolen when they had departed in haste during the evacuation of the city. Mira said nothing. She was grateful simply to have a roof over her head. Every day Mira returned to her building on Pushkinskaya in the hope of meeting the postman, desperate for news from her son Moishe (Musenka) in the army, and her husband Yehuda in the gulag. And she petitioned the authorities for a place to live for herself and her daughter. For once she was lucky, and was assigned a room in a communal apartment, but at the expense of another family, who were forced onto the street. The dispossessed family rushed at Mira and beat her in anger and despair at losing their home. With so much of the city destroyed and more evacuees returning by the day, the authorities would juggle the accommodation that was still standing, taking shelter from one family to give to another; a lottery of relief or desolation. The room was ten metres square, with no running water or sewerage. Later it became smaller still, with three meters reapportioned to create a corridor where a cooker was installed. But it was a roof over their heads and it was precious. In this room, nearly a decade later, Ira was born. How Mira found the means to live during this period, Ira doesn’t know. But she suspects it was Mira’s brother, Uncle Avrom, who came to their rescue, as he had during the evacuation of Kiev, finding transport for them and a place to live. Sulochka also told Ira about her cousin Beba. Ira says Beba’s real name was Volf. According to the family tree my grandmother and father drew up he was called Velvl, while his grandson – who now lives in Germany – refers to him as Vladimir. Such are the complications of Jewish genealogy! Cousin Beba was the only relative that did not turn against Mira when she became the wife of an Enemy of the People, after her husband was arrested in 1938 and sent to the gulag. One day Beba visited and saw that Sulochka had grown out of all her warm clothes, and in the dead of winter. He went to the crowded flea market where people bought and sold new and second-hand goods and found her a pair of warm boots. Mira continued to go back to the family’s old home on Pushkinskaya in the hope of seeing the postman and finding a letter from her son or husband. In 1944, Musenka wrote that he was being transferred to the front – to Poland – and that before his departure he would be based at a large camp on the outskirts of Kiev, by the Darnitsia train station across the river Dnieper. Mira and Sulochka were able to visit him there. Musenka was 18 years old and this was the last time his mother and sister ever set eyes on him. This story will be continued in my next article.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed