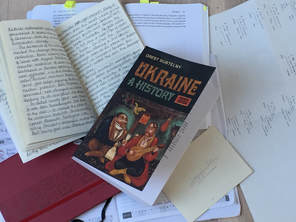

My great as-yet-unwritten novel has not yet started to take form, but its shape is finally becoming slightly less amorphous. The notes on historical background are burgeoning in the lovely soft-backed notebooks with cream-coloured pages that I treated myself to in the hope that they would help inspire my writing. I recently embarked on a dauntingly enormous tome that has been sitting beside my sofa for many months, taunting me with its great heft. At nearly 800 pages, Ukraine: A History by the academic Orest Subtelny, promises to be a valuable resource, but perhaps one that I shall dip into rather than reading from cover to cover in my usual methodical way. I like the book’s dedication: "To those who had to leave their homeland but never forgot it" – people like my grandparents who circumstance forced to travel thousands of miles to forge a new life in Canada. Grandma certainly never forgot her homeland. She talked about it endlessly, so much so that her children – my Dad and aunt – grew up surrounded by her stories, and the inhabitants of a distant Ukrainian village – many of them long dead – seemed more real to them than those of the Canadian city in which they lived. The period that interests me most is the Russian civil war of 1917-22. The book refers to this era as the Ukrainian Revolution. These two events were intertwined, each an integral part of the other. After the Bolsheviks seized power in Russia in October 1917, the revolution turned to civil war as, in Subtelny’s words, “numerous claimants for power in Ukraine and throughout the former empire were embroiled in a bitter, merciless military struggle, complete with large-scale terror and atrocities, to decide who and what form of government should replace the old order”. These “claimants for power”’ were what my grandmother called the banda. They were “rebels and hoodlums, peasants and ex-army officers representing every kind of faction, every ideology imaginable. Some fought for Communism, others for Nationalism, Anarchism, Freedom or Holy Russia. Each recruited fighters to his cause, often luring the impoverished and the illiterate with the promise of food and action, arming them with guns brought back from the war – the other war – and hidden in hayricks or underground hideouts. “It seemed that each banda was competing to be more bloodthirsty than the last. They appeared to take pride in acts of rape and pillage, mutilation and murder. Their armies were each represented by a colour, like pieces in a giant board game. Every banda was competing against all the others, occasionally forging an alliance to gang up on one enemy, only to break the pact a few months later and start fighting again. There were Reds, Whites, Greens and sometimes even Red-Greens and White-Greens and names that instilled fear: Petlyura, Makhno, Zeleny, Denikin. The Greens took their name from their little flat caps and those of Zeleny’s men were yellow. Makhno’s anarchist fighters wore black hats and carried black flags crudely painted with the words ‘Liberty or Death’. The Cossack fighters had scarlet caps, while the Bolsheviks decorated their arms with thick, blood-red bands. As well as those sporting what could pass for a uniform, there were other banda made up of rag-tag bunches of ruffians.” One of the key turning points of the Ukrainian Revolution took place exactly a century ago, in November 1918. Ukraine had been ruled since April of that year by a regime known as the Hetmanate, a conservative Ukrainian government headed by Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky – his title evoking Ukraine’s old Cossack traditions. The Hetmanate existed under German occupation and replaced Ukraine’s year-old Central Rada, a broad but mostly nationalist and socialist council, or soviet, which had come to power following the Russian Revolution. Skoropadsky was a wealthy landowner and part of the Tsarist establishment, but had thrown off his imperialist veneer to become leader of a Free Cossack peasant militia and set about dismantling some of the left-wing policies imposed by the Central Rada. He bestowed on himself sweeping powers and declared the establishment of the Ukrainian State. New Ukrainian-speaking schools popped up across the land, Ukrainian-language school books were hastily published and even two new Ukrainian universities were created. But opposition to Skoropadksy and the Hetmanate soon mounted and spontaneous, fierce peasant revolts spread across Ukraine. Led by local, often anarchistic, leaders known as an otaman or batko, hordes of peasants fought pitched battles against the occupying German troops. The insurrection centred on a town called Bila Tserkva, just west of Kiev and only a few miles from my family’s home in Pavolitch. Thousands of peasant partisans poured into the area. By 21 November they had encircled Kiev and three weeks later the occupying Germans evacuated the city, taking Skoropadsky with them. As a result of the fall of the Hetmanate, the following year total chaos would ensue, but the story of 1919 is one that I will save for later.

2 Comments

Mel Unickow

3/11/2018 01:17:01 am

I found the article interesting and look forward to reading future articles. The chaos that occurred back then seems to continue today. Best Regards , Cousin Mel from Mazatlan , Mexico

Reply

Lisa Cooper

12/11/2018 11:16:13 am

Hello Mel, I'm glad you enjoyed the article. I hope you and Audrey are well and happy -- Lisa

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed