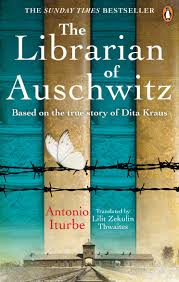

Books have provided me, like many others, with a place to escape during this strange Covid era. Perhaps paradoxically, my escape has not been to happier times, but to the bleakest, most terrible period of mid-20th century history, which has absorbed me during recent months. Bringing myself back again and again to the Holocaust has helped me appreciate all the freedoms we have still been able to enjoy this year, as opposed to those that the coronavirus has taken away. The Librarian of Auschwitz by Antonio Iturbe (translated from the Spanish) tells the fascinating story of Dita Kraus, who was 13 in 1942 when she was deported from her home in Prague to Terezin (Theresienstadt), and later to Auschwitz. Dita – a feisty, strong-minded teenager – and her parents were sent to the family camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau, a showcase area established in September 1943 most likely in case a delegation of the International Red Cross were to come to inspect conditions there. The Nazis wanted to preserve the illusion that children could live in Auschwitz, and to contradict reports that it was a death camp. In the event, though, the International Red Cross inspected Theresienstadt but chose not to come to Auschwitz after all, in the mistaken understanding that Theresienstadt was the Nazi’s final destination for Czech Jews. Perhaps if the visit had taken place, just perhaps, it would have created such a public outcry that the allies would have been forced to take action. But once the threat of a Red Cross visit disappeared, the family camp had no further purpose and was liquidated in July 1944. Of the 17,500 Jews deported to the family camp, only 1,294 survived the war. Prisoners at the family camp were not subjected to selection on arrival and were granted several other privileges. Rations were a little better, heads were not shaved and civilian clothes were permitted. Family members were able to stay together; males and females were assigned to separate barracks, but were still able to meet one another outside their quarters. Prisoners were given postcards to send to relatives in an attempt to mislead the outside world about the Final Solution. Strict censorship, of course, prevented them from telling the truth. Prisoners in the family camp had “SB6” added to the number tattooed on their arm, indicating that they were to receive “special treatment” for six months. When the six months were up, each transport was liquidated and a new one took its place. In spite of the privileges and so-called special treatment, living conditions were still abysmal by any standards other than those of a concentration camp, and the mortality rate was high. Dita’s father died of pneumonia in the camp. The family camp was home to a clandestine school, established by Fredy Hirsch – a German Jew and former youth sports instructor – who persuaded the authorities to allow block 31 to act as a special area for the camp’s 700 children. Inside the block, the wooden walls were covered in drawings, including Eskimos and the Seven Dwarves, stage sets for plays performed by the children. Stools and benches took the place of rows of triple bunks. Education was officially forbidden, with the children permitted only to learn German and play games. But that did not prevent Hirsch and his teachers from organising lessons on all manner of subjects, including Judaism. There were no pens or pencils, of course, and the teachers would draw imaginary letters or diagrams in the air rather than on a blackboard. And inside block 31 was something else, something “that’s absolutely forbidden in Auschwitz. These items, so dangerous that their mere possession is a death sentence, cannot be fired, nor do they have a sharp point, a blade or a heavy end. These items, which the relentless guards of the Reich fear so much are nothing more than books: old, unbound, with missing pages, and in tatters. The Nazis ban them, hunt them down.” Dita became the custodian of block 31’s motley collection of books, which had been secretly taken from the ramp where the luggage of incoming transports was sorted. There were eight books – eight small miracles – which included an atlas, a geometry book, a Russian grammar, A Short History of the World by H G Wells, a book on psychoanalytic therapy, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas and a Czech novel: The Adventures of the Good Soldier Svejk, as well as a Russian novel with no cover. The school also had six “living books”, stories learnt by heart and recounted by the teachers. Dita cared for her eight books like she would her own children, caressing them, putting their pages back in order, gluing their spines and trying to keep them neat and tidy. She took huge risks on their behalf, removing the books from their hiding place each day and lending them out to teachers as requested, always alert to the possibility of an unplanned inspection or visit from the SS. Despite the many books I’ve read about the death camps, and a visit to Auschwitz in 2018, literature on the subject still has the power to shock. In this book, for me, it was this passage, in which a woman, together with her young son, is told that they will be transferred from Birkenau to be with her husband – a political prisoner – in Auschwitz, three miles away: “Miriam and Yakub Edelstein have sharp minds. They immediately understand why they have been reunited. No-one can begin to imagine what must pass through their minds in this instant. “An SS corporal takes out his gun, points it at little Arieh, and shoots him on the spot. Then he shoots Miriam. By the time he shoots Yakub, he is surely already dead inside.” This is a beautifully written story about a time and place that was hideous and brutal. As the author says, “The bricks used to construct this story are facts, and they are held together in these pages with a mortar of fiction.” I urge you to read it for yourself.

1 Comment

Dawn Roberts

7/9/2020 07:50:57 pm

An excellent summary of an excellent book! I, too, have read a lot of non fiction lately, predominantly the Holocaust, and have said on many occasions that lockdown isn’t hardship. It’s just that we are so used to unlimited freedom of movement and speech that we take it for granted. Let us never forget this dark period in our (fairly recent) history and be thankful for all that we have today.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed