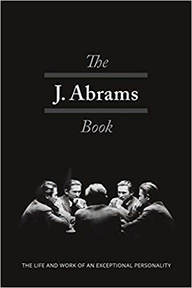

The Jewish Review of Books published an intriguing piece in its latest edition, featuring two books about anarchists, both of them Jews who had recently immigrated to the US from Tsarist Russia. The anarchist movement has been largely forgotten amid the later polarisation of the world between Communism and Capitalism. But in the US alone, in the early 20th century there were several hundred thousand anarchists, and they outnumbered Marxists in the country. They stood for the creation of a peaceful, stateless anti-authoritarian society, in which people would freely join together to govern themselves. Anarchists played a significant role in both the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Spanish Revolution of 1936. Jewish immigrants from working-class families were prominent in the anarchist movement in the US, pursuing arguments in New York’s lively radical Yiddish-language subculture. They were not ashamed of their Jewish heritage, but rejected Judaism and held an annual Yom Kippur Ball, mocking the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. Jacob Abrams was born in present-day Ukraine in 1886, coming to America in 1908. He gained fame and notoriety in the US after he organised a protest in August 1918 in reaction to Washington’s decision to send 15,000 troops to intervene in revolutionary Russia. They distributed leaflets in English and Yiddish around New York’s immigrant district, the Lower East Side, calling for workers to participate in a general strike. “An open challenge only will let the government know that not only the Russian Worker fights for freedom, but also here in America lives the spirit of Revolution.” Abrams and his co-conspirators were swiftly arrested and tried under the espionage act, receiving sentences of up to 20 years. Their appeal went to the US Supreme Court and became famous as a trial for free speech, and a compromise was reached offering the prisoners’ release provided they leave for Russia – their birthplace – at their own expense and never return to the US. In November 1921 they set sail for the Soviet Union. Abrams spent five years in the USSR, and quickly gained the impression that it was not the workers’ utopia that he had dreamed of. He and his wife were assigned a space in a communal apartment, a single room shared with three other people. He found people hungry and dressed in rags. He gained permission to set up Russia’s first automatic laundry, which operated out of the basement of the foreign ministry. But his protestations about inefficiencies and graft were ignored and eventually led to charges of anti-Soviet activity being brought against him. He quit his job and was immediately evicted from his home as his accommodation was tied to government service. He eventually managed to convince the authorities that he would be of more value to the revolution if he continued his work abroad and, surprisingly, he and his wife were given passports. They left for Mexico, where Abrams became director of the Jewish Cultural Centre and published Yiddish books and newspapers, and later became a close friend of the exiled Leon Trotsky. Sam Dolgoff was born in Vitebsk, in present-day Belarus, in 1902. His father Max had been a rebel back in Russia, where he enraged his own father, a rabbi, by renouncing religion. He left for America to avoid being conscripted into the army, and was joined by his wife and son in 1905. Sam was a socialist by the age of 14, but he soon concluded that the socialists were mere reformers who were not really interested in uprooting the capitalist system or transforming society. When he started expressing these views at meetings and publishing his ideas he was expelled from the socialist party for insubordination. He joined the Industrial Workers of the World in 1922, becoming a migratory worker and activist. He is described as having “a strong face, a rugged Russian Jewish face, wild black hair swept back, acute black eyes behind the glasses, a prominent nose,” and apparently looked like he combed his hair with an eggbeater. Later, in New York City, he joined with a group of Italian anarchists to found the Vanguard Group, an anarcho-communist group that largely propagated the ideas of the 19th century Russian revolutionary anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Peter Kropotkin, and in 1954 he helped form the Libertarian League, which held weekly forums featuring non-anarchist speakers. In the 1960s, Dolgoff despaired of the new wave of anarchists, whom he described as “half-assed artists and poets who reject organisation and want only to play with their belly buttons”. He scorned the young radicals’ embrace of the new Cuban leader Fidel Castro, decrying him as a Stalinist dictator, and campaigned on behalf of the Cuban anarchists that Castro had attacked and exiled. As the review concludes, both these men accomplished little, they failed to achieve the goal of an anarchist society and to attract enough believers to their cause to keep the movement alive. But “they were dreamers… their dream was a noble one and worthy of being remembered”. For the full review, click here https://jewishreviewofbooks.com/articles/3222/free-radicals/ The J. Abrams Book: The Life and Work of an Exceptional Personality by Jacob Abrams, trans Ruth Murphy Left of the Left: My Memories of Sam Dolgoff by Anatole Dolgoff

1 Comment

|

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed