|

As the end of the year approaches, the war in Ukraine has now been raging for close to 300 days. So much has changed in that time. Ukrainians have seen all life’s certainties upended and endured inordinate suffering – many thousands killed; millions more living abroad; families separated; homes destroyed; energy and water supplies cut. On the other side, Russians face boycotts, mobilisation and a government that ratchets up hate speech and clamps down ever harder on any form of dissent. And even here in Europe, none of us is immune from the effects of the war. I am sitting typing by the fire in the kitchen, wrapped in blanket and wearing a woolly hat because of the soaring cost of heating my home.

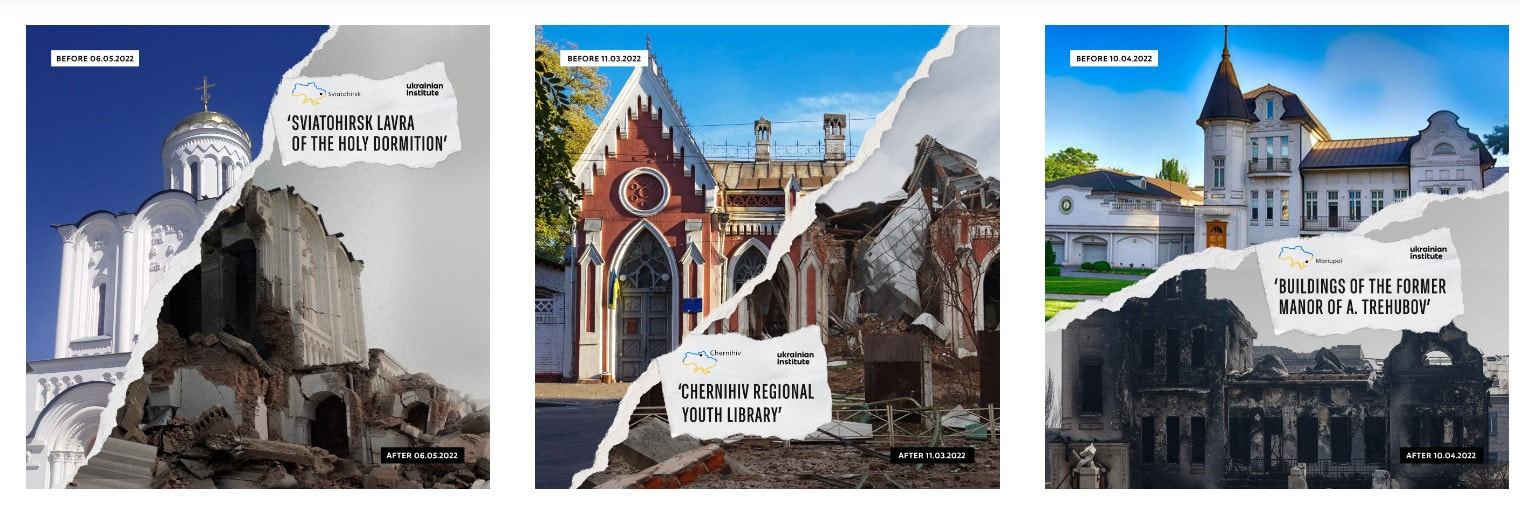

In his now famous speech that preceded the Russian invasion, Russian president Vladimir Putin denied Ukraine’s right to statehood, dismissing its distinct history and culture and referring to its territory as “historically Russian land”. As well as fighting a brutal physical war against Russian invaders and occupiers, Ukrainians are battling on the cultural front, as a way of countering Putin’s twisted arguments. As the rest of the world watched events unfold with a mix of horror and enormous admiration for the resilience and spirit demonstrated by Ukrainians, we too began to embrace Ukrainian culture. Interest in Ukrainian literature spiked, with publishers and translators fast-tracking projects to get works by Ukrainian authors to an English-speaking audience. UK sales of books by Ukraine’s best known living novelist, Andrey Kurkov, increased by 800% in the early weeks of the war. Kurkov himself became a voice for Ukraine in the wider world, encouraging readers in the West to learn about his country and its history. In October he published Diary of an Invasion, detailing his own experiences of the war. Interest in Ukrainian music has also flourished, with Ukrainian performances slotted into concert programmes everywhere from international venues to village halls. Overwhelming public support propelled Ukraine’s entry, Kalush Orchestra, to an emphatic victory at this year’s Eurovision Song Contest in May. And the newly formed Ukrainian Freedom Orchestra – made up of Ukrainian musicians, many of them now living in Europe as refugees – was added as a special late addition to this year’s Proms at London’s Royal Albert Hall. In contrast, many Russian performers, composers and artists have been dropped from programmes in the West. London’s Royal Ballet, for example, adopted a policy of avoiding working with Russian state actors, including the Bolshoi, as well as individuals associated with the Putin regime. Many other organisations have taken a similar stance, but continue to work with Russian artists who refuse to identify with the Kremlin. Ukraine’s culture minister Oleksandr Tkachenko has called for a complete cultural boycott, urging the country’s allies to put a stop to performances by Russian composers until the end of the war. No Russian music can be performed in Ukraine for the foreseeable future, although the cultural boycott does have some limits. The national music academy in Kyiv voted against ditching its branding as the Pyotr Tchaikovsky conservatory to rename itself after the Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko instead. A cultural boycott would not amount to “cancelling Tchaikovsky”, but would be “pausing the performance of his works until Russia ceases its bloody invasion,” Tkachenko told The Guardian. He described the war as “a civilisational battle over culture and history” in which Russia is actively “trying to destroy our culture and memory” by insisting that the two states constitute a single nation. Italy’s world-renowned opera house La Scala is having none of it, opening its new season earlier this month with the Russian opera Boris Godunov, while protestors lined the streets outside. Russian media reported widely on the production, making it a propaganda win for the Kremlin. Notably, the Polish National Opera in Warsaw cancelled scheduled performances of the same opera following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, saying it would consider staging it in peacetime instead. Russia has long used culture as a form of public diplomacy in its cold war with the West. Its greatest soft power success in recent years was probably the 2018 World Cup finals, which did wonders for Russia’s reputation as the country opened its arms to football fans and showcased the glitz and glamour of the new Russia, belying its recent history as a dangerous threat amid wars in Eastern Ukraine and Syria, and the poisoning of former intelligence agent Sergei Skripal in the UK. The three key pillars of Russian cultural and public diplomacy – cooperation agency Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russkiy Mir Foundation, and the Alexander Gorchakov Public Diplomacy Fund – are controlled and financed by the state and actively promote the Kremlin’s narratives, whether by means of culture, youth exchanges, or support for academic cooperation. They also finance a network of other civic organisations and cultural institutions that help make up Russia’s propaganda machine. The physical destruction of Ukraine’s cultural heritage has been a feature of the Russian invasion too. According to Unesco, more than 200 historical sites, buildings and monuments have been damaged. Ukraine puts the figure at up to 800, with thousands of artifacts removed or destroyed. Most recently, before fleeing Kherson last month, Russian forces emptied the city’s local history museum and art gallery, transferring the paintings and artifacts to Crimea. During the occupation of Kherson, giant billboards showed images depicting the iconic Russian poet Alexander Pushkin and other Russian historical figures and highlighting their connections to the city. One means Ukraine is using to fight back in the culture war is a project from Kyiv’s Ukrainian Institute titled Postcards from Ukraine, which aims to draw attention to Ukrainian architectural heritage and cultural monuments that have been destroyed or damaged since the Russian invasion began. It is a major international campaign, financed by USAID, that presents before-and-after pictures of damaged buildings and helps showcase how Europe is losing an important part of its cultural heritage. Volodymyr Sheiko, director of the Ukrainian Institute in Kyiv, sees culture as a means the country can use to counter Ukraine war fatigue. He says: “The number of times Ukraine is mentioned [in the media] has decreased tenfold compared to February and March. But this fatigue can be prevented if we do not talk about ourselves exclusively from the position of victim. If we inundate people every day with photographs from the front, this truly exhausts them. But this is not the only part of the Ukrainian story today. We also have a history of struggle, of heroism, of a fantastic social solidarity. And this is part of our dynamic and creative culture. We should present this culture as broadly as possible because it can astonish and impress and be competitive. This does not cause fatigue. On the contrary, it entertains and fascinates, and allows us to keep people's attention on the wave of solidarity with Ukraine.” Postcards from Ukraine can be found here: https://ui.org.ua/en/postcards-from-ukraine/

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed