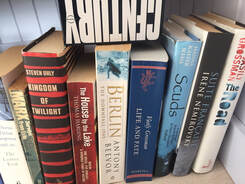

I’ve had a copy of Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate taunting me from my bookshelf for several years. I’ve been meaning to read it, really meaning to, ever since my Dad gave it to me. But at nearly 900 pages, somehow I’ve never found the time. I have read other, less hefty, works by Grossman in the meantime, and have found them fascinating. Now a new biography of the writer by Alexandra Popoff, a former Moscow-based journalist now based in Canada, is finally goading me into action and I plan to devote the coming summer to finally reading Life and Fate. Grossman is an intriguing character, a celebrated Soviet writer who later turned against the regime. His conscience forced him into the tormented double life of a Soviet intellectual, trying to express his doubts about the Soviet system in ways that would not lead to his arrest. Life and Fate, however, was an incendiary work by Soviet standards. A panoply of characters and sub-plots centred around the events of World War II, it is often compared with Leo Tolstoy’s monumental War and Peace, which shares a similar structure based on an earlier war – Napoleon’s unsuccessful Russia campaign. But what made it so controversial to the Soviet censors is its comparison of the USSR with Nazi Germany and Stalin’s persecution of the Jews with Hitler’s holocaust. Mikhail Suslov, the chief Communist party ideologue, told Grossman, “Your book contains direct parallels between us and Hitlerism…Your book defends Trotsky. Your book is filled with doubts about the legitimacy of our Soviet system.” Its publication was out of the question. Grossman was born in 1905 to a Jewish family in Berdichev, Ukraine, a town with one of Europe’s largest Jewish populations. His early novels, published in the 1930s, were mostly typical of Soviet literature at the time and Grossman was promoted by the regime’s most influential writer Maxim Gorky. But even then, some of his short stories were banned and he could be considered lucky for avoiding arrest during Stalin’s purges of the late 1930s. During World War II, Grossman worked as a journalist for the army newspaper Red Star, reporting from the front line on the battle for Stalingrad and the fall of Berlin. He gained access to the Nazi death camp at Treblinka, near Warsaw, shortly after it was destroyed. This chilling experience formed the basis for his article ‘The Hell of Treblinka’, published in September 1944, which was one of the first accounts of the true horror of the Holocaust to reach the outside world. In it he writes: “It is infinitely painful to read this. The reader must believe me when I say that it is equally hard to write it. ‘Why write about then?’ someone may well ask. ‘Why recall such things?’ “It is the writer’s duty to tell the terrible truth, and it is a reader’s civic duty to learn this truth. To turn away, to close one’s eyes and walk past is to insult the memory of those who have perished.” Grossman completed Life and Fate in 1960, at a time when Soviet literature was enjoying a period of relative liberalism during the post-Stalin Khrushchev ‘thaw’. But like Boris Pasternak’s better-known work Doctor Zhivago, the novel could not be published in its homeland. Suslov told Grossman that there was no question of Life and Fate seeing the light of day for another 200 years. Every copy of the manuscript was confiscated by the KGB in 1961, with orders to take not just the typewritten pages, but any sheets of used carbon paper and even the typewriter ribbons used to write it. It is thanks to the emigré dissident Vladimir Voinovich that the book made its way to the West on microfilm. The Russian text was published abroad in 1980 and in English five years later. Life and Fate was finally published in the Soviet Union in 1988, some 24 years after Grossman’s death. In a couple of months or so I will write my own thoughts about the novel, once I’ve completed the monumental task of reading it. Vasily Grossman and the Soviet Century by Alexandra Popoff is published by Yale University Press Life and Fate by Vasily Grossman is published by Vintage Classics

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed