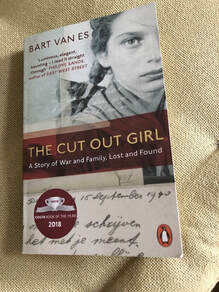

Coronavirus has caused the greatest economic disruption globally since the Second World War and, for those of us who did not live through it, this would be our World War moment – a time of sacrifice, when we make huge changes to our own lives to help save those of others. So we were told repeatedly as governments around the world shut down shops, businesses and schools and imposed previously unimaginable restrictions on the lives of their citizens. The comparison always seemed a glib one. Nothing will ever compare with the untold suffering forced upon hundreds of millions of people in World War Two. Perhaps for those on the front line of this pandemic – our healthcare workers and those looking after the elderly – the comparison may ring true, but for most of us, lockdown has been unusually peaceful. For me personally, the hecticness of everyday life has been stripped away, to be replaced largely with home-schooling and gardening – busyness of a different kind that has forced my blog to take a back seat for the last three months. But the wartime analogies seeped into me and for this reason most of my reading in recent weeks has centred around experiences of World War Two. Now my children are finally back at school for a couple of days a week, I intend to spend some of my new-found time writing up my thoughts about the books I have read and how I feel they chime with current events. One book I found deeply absorbing is The Cut-Out Girl by Bart van Es, the tale of a young Jewish girl in the Netherlands who is sent away by her parents in 1942 in the hope of saving her life. Their dream is realised, as the mother and father are deported to Auschwitz just weeks after giving up their adored only child. Meanwhile young Lientje passes from one Christian family to another, from one town to another, gradually changing from a friendly and vivacious eight-year old to a solitary and withdrawn 11-year old. With her first foster parents she is welcomed as one of the family and able to play outside freely with the other children. Later she is forced into hiding and by 1945 she is kept as a house servant, made to feel unwelcome and suffering abuse. Lientje’s experience is far from unique in the Netherlands. Unlike other occupied countries, Holland’s socialist and resistance organisations developed networks to rescue Jewish children following the Nazi occupation and place them in hiding. Anne Frank was just one of many Dutch children tucked away in hidden rooms, attics and cellars across the country. Many thousands of hidden war children – Jews who, unlike Anne, were given up by their parents in the hope of saving them – survived, but at great emotional cost. For me the most shocking aspect of this book is the level of complicity among the local population and the lack of resistance to the Nazi occupiers – in a country that has a longstanding reputation for tolerance. Four-fifths of Holland’s Jews were murdered during the war, more than double the proportion in any other western European country. Van Es offers several reasons for what he terms “the exceptionally low chance of survival”. The country’s population was largely urban, persecution began early, escape across borders was almost impossible, and registration, aided by the Jewish Council, was efficient. Another factor was help from the local population, thanks to a bounty of 7.5 guilders offered for every Jew caught, which made people all too willing to inform on their Jewish neighbours and helped the local police to exceed the quotas for Jew-hunting set by their German masters. Added to this, in July 1942 the Dutch Reformed Church refused to make a statement of disapproval about the mass deportation of Jews. It wasn’t until late 1943 that the Church decided to reverse its position and backed active resistance, telling its members to protect their fellow citizens even at cost to themselves. This enabled Jews like Lientje to go into hiding with families in rural areas, which were inherently safer. The author intersperses Lientje’s wartime experience with the story of his own present-day research, including interviews with Lien, as she is now known, in her 80s. Comparisons between the Dutch countryside of today, connected by wide, well lit motorways dotted with bright car showrooms, contrast with the bleak, flat, empty lands of three-quarters of a century ago. A park close to Lien’s apartment in Amsterdam, where she and the author go for a stroll, was a German military camp during the war, surrounded by barbed wire and embedded with deep concrete bunkers. Other comparisons between the two eras also resonate. The long period of economic hardship and austerity in Germany that followed the First World War; and now the global financial crisis of 2008, both pushed voters further to the right in the years that followed. This loss of faith in the political centre ground has enabled the election of an American president who is unfit to govern, while emboldening powerful leaders in countries without democratic elections. The blind belief in government propaganda of the last century has transmuted into an unquestioning faith in ‘fake news’ on social media at the expense of expertise and journalistic rigour. The other obvious parallel is the alarming rise in racism and anti-immigrant discourse and attacks in recent years, including many perpetrated against Jews. But perhaps the demonisation of the Muslim community following terror attacks by Islamic extremists – culminating in President Trump’s attempts to impose a ‘Muslim ban’ – comes closest to the anti-Semitism of the Nazi era. Yet the newly resurgent Black Lives Matter movement brings hope of a rising opposition to anti-immigrant sentiment, and a hope that society will not return to the division of the 1930s and 1940s. Thousands of people around the world, most of them young and many of them white, are risking their own health to attend marches and stand up to racism. The rise in people power has even prompted corporations to make statements and put their money where their mouth is, withdrawing advertising from platforms that are not doing enough to root out racism. I cannot help but think back to the past, when there were no marches, no boycotts. Anti-Semitism was rife in society and whipped up by propaganda, in the Soviet Union and elsewhere, as well as in Germany. The number of citizens standing up to racism was tiny, hardly surprising given that they did so at great risk to their own lives. In the words of the famous 1946 poem by the German Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller: First they came for the Communists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Communist Then they came for the Socialists And I did not speak out Because I was not a Socialist Then they came for the trade unionists And I did not speak out Because I was not a trade unionist Then they came for the Jews And I did not speak out Because I was not a Jew Then they came for me And there was no one left To speak out for me And there was no one left To speak out for me

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed