Last week the UK elected a new government and a new prime minister. Whatever we thought of the last bunch (and the results show most of us really didn’t think much of them at all), the majority of Conservative MPs who were unseated or lost their government posts were surprisingly magnanimous in defeat. Of particular note were the words of the outgoing Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, who retained his seat only by the narrowest of margins. For those less familiar with British politics, Hunt was catapulted into the role of finance minister to steady the ship during the disastrous and short-lived premiership of Liz Truss, after she was forced to sacrifice her chosen chancellor and partner-in-crime, Kwasi Kwarteng. Hunt had previously been health minister from 2012-2018 and became so unpopular that many gave him a nickname that replaced the first letter of his surname with a C. However, he won over some of his detractors with these words, spoken at around 5am on Friday morning. “A message to my children – who I sincerely hope are asleep now – this may seem like a tough day for our family as we move out of Downing Street, but it isn’t. We are incredibly lucky to live in a country where decisions like this are made not by bombs or bullets, but by thousands of ordinary citizens peacefully placing crosses in boxes on bits of paper. Brave Ukrainians are dying every day to defend their right to do what we did yesterday and we must never take that for granted. Don’t be sad, this is the magic of democracy”. Indeed, Ukraine had been scheduled to hold its own presidential elections in March or April this year. But Kyiv enacted martial law on 24 February 2022 in response to Russia’s full-scale invasion and the country’s legal framework does not permit elections to be held when martial law is in effect. Even if the law had allowed elections to go ahead, this would have been impossible in practical terms, with millions of Ukrainians living abroad in fear for their safety and the threat of Russian missiles and bombs targeting busy polling stations. In contrast, Russia did hold a presidential election back in March, which Vladimir Putin won by a landslide far eclipsing that of the British Labour Party. The difference, of course, is that one election was free and fair and the other wasn’t. Reports of ballot-stuffing and coercion were widespread in Russia, while any genuine opposition candidates were barred. Just one, a former member of Russia’s state duma running on an anti-war platform, made it through the vetting process. Boris Nadezhdin was careful to play by the Kremlin’s rules, avoiding direct criticism of Putin. Russia-watchers had considered he might be allowed to remain on the ballot to create a semblance of competition, and to provide a narrative for Putin to rally against. But Nadezhdin proved too popular, with a hundred thousand Russians flocking to sign supporter lists for him, and was barred from standing on technical grounds just weeks before polling day. Voting in Russia’s presidential election also took place in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine, where there were reports of residents being forced to vote at gunpoint or amid threats of withholding medical care or other social benefits. Vadym Boychenko, the Ukrainian mayor of Mariupol, described how a woman “accompanied by two Chechen military men with machine guns” turned up at his neighbour’s apartment with a ballot box and made it clear that voting was not optional. At least 27 Ukrainians who refused to vote were arrested, according to human rights activists. A high turnout was important to Putin to help silence dissent and present himself as a legitimate and popular leader. In Russia itself, thousands of citizens headed to the polling stations at midday as a form of protest inspired by the late opposition leader Alexei Navalny, who died in February in an Arctic prison, in an action called “noon against Putin”. Some visited Navalny’s grave in Moscow to symbolically cast their vote for him. In a country that punishes any form of anti-war criticism with a jail sentence – often accompanied by torture – even these mildest of protests were very risky and dozens were arrested. Not only does the magic of democracy in the UK contrast sharply with the presidential election in Russia, but the gracious and orderly transfer of power is diametrically opposed to the last US presidential election, when Donald Trump refused to concede and attempted to overturn the result by inciting an insurgency in Washington DC. Five people died in the riot at the Capitol Building on 6 January 2021, as the country and the rest of the world looked on in horror. We can only hope that the upcoming US elections will run as smoothly as those in the UK. Photo by Element5 Digital on Unsplash

1 Comment

Earlier this month a blue plaque was unveiled outside a little grocer’s shop in the small town of Harlech in North Wales. I’ve been a regular visitor to Harlech all my life, as it’s just down the road from the remote farmhouse where my grandparents spent most of their retirement, and which my brother and I recently inherited. Harlech is best known for its medieval castle - a Unesco world heritage site, its long, sandy beach and, recently, a tussle with Dunedin in New Zealand to be home to the world’s steepest street. I for one knew nothing of Harlech’s link with an elite secret commando unit of Jewish refugees, sometimes referred to as the real life Inglourious Basterds of the Quentin Tarantino film. Number 3 (Jewish) Troop, No 10 Commando – otherwise known as X Troop – was established in July 1942, on the suggestion of Lord Mountbatten, when Britain seemed on the brink of defeat. It was to be a highly trained commando unit made up almost entirely of Jewish refugees from Germany and Austria who had escaped on the Kindertransports that brought young Jews to Britain. They were a disparate group made up largely of intellectuals, artists and athletes, many of whom had been interned as enemy aliens, having lost their homes and families to the Nazis. All were hellbent on revenge. Because of the men’s origins, and the dangers they would face if captured, the very existence of the troop was shrouded in secrecy. Members of the unit had to adopt fake British names and personas and destroy all traces of their former selves. Winston Churchill himself gave the troop its name. “Because they will be unknown warriors…they must be considered an unknown quantity. Since the algebraic symbol for the unknown is X, let us call them X Troops,” he said. X Troop operated as a commando unit, using advanced combat skills to fight behind enemy lines. Described as a suicide squad, many did not come back alive. Members of the troop were attached to other units rather than fighting together as a group, but were referred to as the most effective commando unit in World War II. Their daring undercover missions included in an operation to steal a German Enigma code machine. X Troop fighters were also trained in counterintelligence and played an important role in interrogating German soldiers as soon as they were captured, making use of their native language skills. After the war, members of X Troop went on to become Nazi hunters, routing out hidden party members and gathering intelligence and documentation used at the Nuremburg trials. One member of the troop made an arduous journey across Germany to rescue his own parents from the Theresienstadt concentration camp. The troop first assembled in a traditional stone building on Harlech’s main street, now the blue-plaqued grocer’s shop, and used it as a social club. Its commanding officer, Major Bryan Hilton-Jones, a Cambridge modern languages graduate, was born in Harlech and grew up in Caernarfon, another North Wales town famous for its castle. The group spent nine months training in the rough terrain of Snowdonia, including running nearly 40 miles from Harlech to the top of Snowdon – the highest mountain in England and Wales – and back, and scaling the walls of Harlech Castle. The BBC quotes Bryan Hilton-Jones’ daughter, Nerys Pipkin, saying, "Dad was a quiet man, but legendary for his physical fitness and sense of humour…he was as tough as nails and the sort of man who inspired people – just the right type of person to lead this unit." Major Hilton-Jones was a father figure to the troop and won their utmost loyalty and respect. He died near Barcelona in 1969 aged just 51, in a car crash that also killed two of his daughters and seriously injured his wife Edwina. Bryan Hilton-Jones’ friend Kevin Fitzgerald wrote of him in an obituary, “No one could tire him. Many so-called hard men were glad to fall back a little after the first five or six hours. They could outclimb him (some of them) but never outwalk him. He had a map of Wales in his head and never failed to select the hardest, longest distance between any two Welsh points. It was always worth it; he was the perfect companion.” In 1999, a large memorial stone was erected in Aberdyfi, 20-odd miles south of Harlech, where the soldiers were billeted and did much of their training. The story the clandestine commando unit is told in Leah Garret’s 2021 book X Troop: The Secret Jewish Commandos of World War II.  Every day this month, Holocaust survivors from around the world are posting videos of themselves reading from Holocaust denial articles found on social media as part of a campaign titled #CancelHate organised by the New York-based Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany. The Claims Conference, as it is better known, launched the project to illustrate how Holocaust denial and distortion can not only rewrite history, but perpetuate antisemitic tropes and spread hate. It comes at a time of rising antisemitism around the world, triggered by Israel’s horrific military campaign in Gaza in response to the deadly Hamas attack of 7 October. “The world is a volatile place right now. Social media offers individuals a place to hide while they spread words of hate. This campaign shows that these are not victimless posts – these mean and vile words deny the first-hand testimony of each and every Holocaust survivor, their suffering and the suffering and often loss of their families,” says Gideon Taylor, President of the Claims Conference. Recent studies conducted by the Claims Conference show a growing gap in basic knowledge of the Holocaust, leaving younger generations increasingly vulnerable to denial and distortion. An astonishing 49% of young American adults have come across information online denying or distorting the truth about the Holocaust. Elsewhere, in the UK, 29% of adults reported seeing denial or distortion on social media. In Canada, 22% of Millennial and Gen Z adults were not even sure if they had heard of the Holocaust. Meanwhile, in Russia, President Vladimir Putin’s government repeatedly manipulates the history of the Holocaust for its own political purposes, falsely portraying Ukrainians as Nazis and even accusing Jews of being Nazis. “I could never have imagined a day when Holocaust survivors would be confronting such a tremendous wave of Holocaust denial and distortion, but sadly, that day is here. We all saw what unchecked hatred led to – words of hate and antisemitism led to deportations, gas chambers and crematoria. Holocaust survivors from around the world are participating in this campaign to show that hate will not win,” says Greg Schneider, Executive Vice President of the Claims Conference. With the last generation of Holocaust survivors now in their eighties and nineties, the number of survivors able to tell their stories dwindles year by year and it will soon be too late to hear their testimonies direct. Listening to these old men and women recounting brief snippets about events that happened to them as young children, the power of their words is still strong, their emotion palpable. Each video shows a Holocaust survivor introducing themselves, reading social media posts about Holocaust denial, then briefly recounting some of their own experiences of the Holocaust. Every video ends with the tagline, “Words matter. Cancel hate”. Here’s an example, presented by a Jewish American therapist, social worker, author and academic, who was born in Poland: “My name is Tova Friedman, I am a holocaust survivor. Let me read to you words of a denier: ‘Dachau was full of Catholic religious and priests, not Jews. Auschwitz Jews had swimming pools, orchestras, and brothels.’ These are the words of a denier. Well, let me tell you, at the age of 5½, I and my mother and father got off the cattle trucks in Auschwitz. I was taken away from my mother and I spent six months of my life with inhuman conditions – starvation, illnesses. I saw the death chambers, I saw the smoke. We were tattooed. There were so many incidents – beatings, starvation, typhus. Out of my town, out of hundreds of children, five were left. Words matter. Cancel Hate.” Abraham Foxman, an American lawyer and former national director of the Anti-Defamation League, says, “I survived the Holocaust, but 13 members of my immediate family were murdered because they were Jewish. Holocaust denial on social media isn’t just another post. These things we say matter. Posts that deny the Holocaust are hateful and deny the suffering of millions of people. We must take our words seriously. Our words matter.” Hedi Argent MBE, a 94-year-old British author, fled her home in Austria with her family in 1939, just weeks before the border closed. “My family was turned out of our home…because we were Jews. My father was forced to scrub the streets and was later arrested for making anti-Nazi comments, yet we were the lucky ones. The 17 members of my family who were murdered were not lucky. The Holocaust did happen,” she recounts. Herbert Rubinstein was five years old when he and his mother were taken from the Jewish ghetto in Chernivtsi and herded onto a cattle truck bound for the camps. They were among the few lucky ones – having managed to obtain forged Polish identity documents while living in the ghetto, they were removed from the truck and fled, seeking refuge in several countries of Eastern Europe until the end of the war. “I lived through the Holocaust. Six million were murdered. Hate and Holocaust denial have returned to our society today. I am very, very sad about this and I am fighting it with all my might and strength. Words matter. Our words are our power,” he says. Watch the videos here https://www.claimscon.org/cancelhate/ or follow the Claims Conference on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ClaimsConference  Exodus: a mass departure or emigration, taken from the Greek word Exodos, meaning “the road out”. The Exodus tells the story of the Israelites’ journey from slavery in Egypt led by Moses, marked this week as Jews around the world celebrate Passover. It feels like a fitting time to read accounts of a much more recent exodus. Exodus-2022 is a research project documenting the stories of Jewish Ukrainians fleeing their homeland in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. It is the brainchild of Michael Gold, a journalist and researcher of Jewish life with 30 years’ experience in Ukrainian and Israeli media, most recently as Editor-in-Chief of Hadashot, the largest Ukrainian Jewish newspaper. As the Exodus-2022 website says: The blood of Jewish refugees, of course, is not redder than that of others. However, the official objective of the Russian "special operation" was declared to be denazification and protection of the Russian-speaking population. That is why the stories of Russian-speaking Jewish refugees, whose lives were destroyed by the "liberators of Nazism," are especially indicative. In these desperate times, stories of horror and loss have become commonplace. From the slaughter of Bucha and destruction of Mariupol to the murderous attacks of 7 October and annihilation of Gaza, we tally victims by the tens of thousands and all too often pause only briefly to consider individual experiences. Exodus-2022 gives voice to some of those who have suffered, gives them time and space to chronicle and preserve their own personal testimonies about the days, weeks and months following the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Here is Irina Zhivolup from Izyum, near Kharkiv: Why didn’t people run away immediately? Nobody believed that they would level the town like that. After all they destroyed schools, churches, buildings that survived both world wars. Izyum was being razed to the ground… For one day it seemed to be a little quieter, and then in the evening, on March 6, the dog started whining. I understood that it was a raid and then a Grad rocket hit directly in the hallway, where all of us were standing: me, mom, son, husband, and dog. Only I survived. I dug them out. I don’t know where I got the strength - head cracked open, all covered in blood, both legs broken. But I managed to pull the beams away. My son died in my arms, probably from internal bleeding. We all wear glasses, and all the glasses remained intact. So strange… Don’t know why I survived, but I crawled into the house, found some water, climbed into bed, put on my son’s jacket and a hat, and I stayed like that for eight days - no windows, no roof, freezing cold of -10C, rockets flying around the clock, and the bodies of my family lying on the doorstep. Victoria Druzenko managed to flee from Bucha, just north of Kyiv, when a humanitarian corridor opened on 10 March 2022: There were destroyed houses on both sides of the road, along with unexploded shells. By the Epicenter supermarket there was a shot-out car with dead bodies inside. I could even see the colour of the woman’s hair inside – it was red. We turned towards Vorzel and saw a burned-out car with white cloth and a “Children” sign. I thought: how many cars like this will we see on the way and could we end up like this? My friend had a daughter and her classmate with her family... in a car like that. The parents survived, but the girl did not. Victoria made it out to Lviv and then to Israel. What is left behind? she asks. Behind our building is a mass grave, where 76 people were buried in bags on March 11, 2022. That was the first time the Russians gave permission to collect the bodies that were lying on the streets. They buried more after and that’s not counting the ones buried in yards, in gardens, in flowerbeds. And how many people were left in basements and garages in other neighbourhoods: on Yablonskaya, by the glass-manufacturing plant etc… Plus a whole section of nameless graves at the cemetery, where people who could not be identified are buried… Irina Poliushkina lived in Mariupol, where she cared for her elderly, bed-ridden mother who had been evacuated from Leningrad to Siberia during the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. Irina sent her 16-year-old daughter away with departing neighbours thinking she would be safer, while she, her husband and mother remained in their apartment block. Nearby shelling shattered the bedroom windows. And suddenly it became freezing cold, and our apartment was at -5C. We covered my mother with three blankets and put hot water bottles around her. She spent almost three weeks like that. Leaving her mother in the apartment, Irina and her husband sheltered in the basement until their apartment block suffered a direct hit, and fire broke out in the building. Fearing she would be burnt alive, they finally managed to evacuate Irina’s mother to the basement, but others were not so lucky. There were many strikes in the yard of our housing complex and the buildings were hit as well. One family left their grandmother in the apartment and went to the shelter with their child. Anyway, there was a strike between the 8th and 9th floors and she was burned alive. Many old people died from heart attacks. We had to bury them in the yard. We had to put one of the neighbours into a bomb crater. I helped with the burial. The buildings behind us were also burning: it was one big flame all around. They say that now there is a terrible smell there: there was a strike and someone was buried under the rubble. The body did not burn and is decomposing. Testimony follows testimony, almost all from women, and from all over Ukraine – from Kyiv and Chernihiv, Bucha and Irpin, Kharkiv and Izyum, Kherson and Melitopol, Mariupol and Donetsk region, all representing towns that have been devastated by war, livelihoods lost and communities dispersed as the exodus delivered Ukrainians across Europe and beyond. All those who gave testimony have lost friends or family members, and witnessed death in unimaginable circumstances. Some have been seriously wounded themselves. Every story in this collection is harrowing, every as yet untold story still deserves to be heard. Everyone in Ukraine in February 2022, and in Israel and Gaza in October 2023, knows that their whole world can change in a single minute. Read the testimonies for yourself: https://exodus-2022.org/ Next Monday, 18 March, marks the tenth anniversary of Russia’s annexation of Crimea. The move followed swiftly on from Ukraine’s Euromaidan Revolution, which culminated in then-president Victor Yanukovych’s flight from Kyiv in late February 2014. Russia took advantage of the chaos in Kyiv, quickly seizing military bases and government buildings in Crimea.

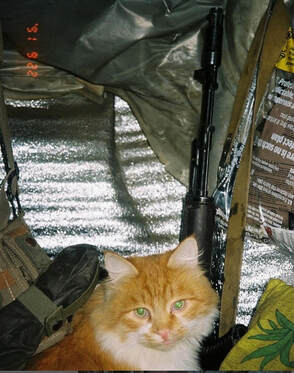

Armed men in combat fatigues began occupying key facilities and checkpoints. They wore no military insignia on their uniforms and Russian president Vladimir Putin insisted the “little green men” – as Ukrainians called them – were acting of their own accord, and were not associated with the Russian army. Only later did he acknowledge the role of the Russian military in the occupation, even awarding medals to those involved. By early March, Russia had taken control of the whole peninsula and its ruling body, the Crimean Supreme Council, hastily organised a referendum for 16 March. The vote went ahead without international observers and was widely condemned as a sham. It offered residents two options: to join Russia or return to Crimea’s 1992 constitution, which gave the peninsula significant autonomy. There was no option to remain part of Ukraine. The result, predictably, was landslide in favour of becoming part of Russia. Turnout was reported to be 83%, with nearly 97% voting to join the motherland, in spite of the fact that Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars made up nearly 40% of the population. The accession treaty was signed two days later. In May that year, a leaked report put turnout at 30% with only half of all votes cast in favour of becoming part of Russia. The annexation of Crimea gave an immediate boost to Putin’s approval ratings, following a turbulent period of pro-democracy protests across Russia in 2011-12. In the face of a weak economy, Putin’s re-election campaign in 2012 had focused on appealing to Russian nationalism, and the swift and bloodless coup in Crimea provided a perfect model for his propaganda narrative. The peninsula had first become part of Russia in the eighteenth century under Empress Catherine the Great, who founded its largest city, Sevastopol, as the home of the Russian Black Sea Fleet. Crimea was part of the Russian republic of the Soviet Union until 1954, when it transferred to the Ukrainian Soviet republic. When the USSR collapsed in December 1991, the successor states agreed to recognise one another’s existing borders. Russia’s seizure of Crimea violated, among other agreements, the UN Charter, the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, the 1994 Budapest Memorandum of Security Assurances for Ukraine and the 1997 Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation and Partnership between Ukraine and Russia. Crimea has experienced significant changes over the past ten years. Ethnic Russians made up around 60% of the population in 2014 — the only part of Ukraine with a Russian majority. Since then, around 100,000 Ukrainians and 40,000 Crimean Tatars are estimated to have left the peninsula, while at least 250,000 more Russians have moved in, pushing the ethnic Russian population above 75%. Many are members of Russia’s armed forces as the Kremlin has built up its military presence on the peninsula. Others are civilians lured by Russian government incentives, such as job opportunities, higher salaries, and lower mortgage rates. Crimean Tatars complain of intimidation and oppression. They are routinely searched, interrogated, accused of terrorism offences and sent to prisons thousands of kilometres away. In prison, they are denied access to medical care, put in isolation cells and forbidden from communicating with relatives or lawyers, or from practising their religion, according to a report in the Kyiv Independent. Of the ethnic Ukrainians who remained in Crimea in the years after annexation, a significant number have since been expelled, imprisoned on political grounds, forced to move to Russia or mobilised into the Russian military. Amid the ubiquitous narrative of Crimea as historically and enduringly Russian, and with public spaces dominated by Soviet and war nostalgia, Crimeans today are afraid to identify as Ukrainian. The high-tech security fence erected on the border between Crimea and mainland Ukraine in 2018 now symbolises separation from family and friends elsewhere in the country. Moscow has poured more than $10 billion in direct subsidies into Crimea, investing heavily in schools and hospitals, as well as military and civilian infrastructure. Crimea today accounts for around two-thirds of all direct subsidies from the Russian federal budget. But many local businesses have suffered, particularly with the decline in tourism, which once accounted for about a quarter of Crimea’s economy. And as Ukrainian products in shops were replaced with higher-priced Russian goods, and later as the value of the rouble fell, prices have spiked. Western sanctions against Russia have also taken their toll on Crimea’s economy. Crimea was one of the Russian regions with the lowest income levels in 2023, according to the Russian state-owned rating agency RIA. Russia has also funded major construction and infrastructure projects, such as the Tavrida highway, which opened in 2020 connecting the east of Crimea with its major cities in the southwest, and the highly symbolic Kerch bridge linking Crimea to Russia, opened to great fanfare by Putin in 2018. Today parts of the Tavrida highway have reportedly begun to buckle, leading to a rise in road traffic accidents. The Kerch bridge has sustained serious damage from Ukrainian attacks and by December last year was still not fully restored. Back in 2014, many Russians in Crimea were euphoric about rejoining the motherland, having always identified with Russian rather than Ukrainian culture and customs. They welcomed the attention that Putin lavished on them, and the influx of Russian cash meant that wages and pensions, now paid in Russian roubles, initially increased. The euphoria has since subsided, and particularly since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many Crimeans are fed up with living in a territory that is isolated, highly militarised, tightly controlled, economically weak and under attack from Ukrainian forces.  This week marks the second anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022. Seeing satellite images of a long line of Russian tanks heading towards Kyiv on that awful morning, few believed that the war would last more than a handful of days; weeks at most. I wrote at the time that Russian president Vladimir Putin had a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him, as he stepped up his attempts to recreate Stalin’s Soviet empire by taking control of Ukraine. Now that whiff has become more of a stench. The death of Alexei Navalny, Putin’s most prominent critic, on 16 February makes the parallels between the two dictators starker than ever. Like Stalin, Putin views the outside world as a hostile and threatening place and brooks no dissent. Stalin subjected his opponents to show trials, found them guilty on trumped-up charges and had them shot. Today, anyone who publicly opposes Putin’s regime, who attempts to tell the truth, expose the corruption, is a grave threat. Putin’s methods of silencing opponents are more varied – imprisonment, poison, shooting, defenestration, a plane falling from the sky. Again like Stalin, Putin heads a cruel and corrupt administration, but has built a personality cult around himself to appear as a paternalistic leader who has the best interests of his citizens at heart. Both regimes have been guilty of hiding or falsifying data and masking the truth with a state-sanctioned view of world events and a thick veneer of propaganda. At the time of writing, the cause of Navalny’s death is unclear. A video taken the previous day showed him looking surprisingly well given the inhumane conditions in which he was incarcerated. His family and legal team have repeatedly been refused access to a mortuary where his body is believed to lie. Just days before Navalny’s death, another Russian politician, Boris Nadezhdin, was barred on technical grounds from standing against Putin in next month’s presidential election. Nadezhdin has been careful to play by the Kremlin’s rules, to avoid calling out or criticising Putin, but he is a vocal opponent of the war in Ukraine. Russia-watchers had considered he might be allowed to remain on the ballot to give the appearance of competition, and to provide a narrative for Putin to rally against. But Nadezhdin proved too popular. A hundred thousand Russians flocked to sign supporter lists to enable him to stand against Putin, so the electoral commission ruled that thousands of the signatures he had gathered were fraudulent. Nadezhdin continues to appeal the ruling, but he must now be looking over his shoulder in case FSB officers are sent to arrest him, just as those who opposed Stalin’s regime lived in fear of a knock at the door in the middle of the night. Another parallel between Putin’s Russia and Stalin’s Soviet Union can be found in the Russian-occupied cities of eastern Ukraine, where the Kremlin is carrying out ethnic cleansing just as it did in the 1940s. In Mariupol, Zaporizhzhia and other cities located in the regions where the Kremlin held rigged referendum votes on becoming part of Russia, the occupying authorities are doing all they can to wipe out Ukrainian identity. Mariupol, before the war a pleasant, leafy coastal city on the Sea of Azov, was besieged and almost razed to the ground in the spring of 2022. Now smart, Russian-built apartment blocks line newly reconstructed avenues planted with lawns and neat rows of trees. In these apartments live recently arrived Russians, shipped in from the Motherland with the promise of better housing, good jobs, higher wages. Many of the previous inhabitants fled the bombardment back in 2022, or were killed or taken prisoner during the siege. What’s more, around 5 million Ukrainians from the occupied territories are estimated to have been deported to Russia in the last two years, including 700,000 children. Those who stayed and survived, or returned, were forced to acquiesce with the occupying authorities, to become Russian. Access to social services, including pensions and maternity payments, is only available to those with Russian passports. This in turn means babies are born to Russian rather than Ukrainian nationals, and inherit Russian citizenship. They will go to schools where they are taught in Russian, be subject to Russian cultural influences and learn a Russian history curriculum filled with hateful rhetoric about Ukrainian Nazis. Refusal to apply for a passport of the occupying power leaves defiant Ukrainians living a shadowy undercover existence, while any show of insubordination is likely to land them in a Russian prison. Crimea has experienced the same manipulations of population and bureaucracy for the last decade, since the Russian annexation in March 2014. Ukrainians were forced out or coerced into giving up their citizenship, native Russians were encouraged to settle, and only those holding Russian passports can access schools, hospitals and social services. Most Russians, and many outside Russia, have long believed that Crimea was not really Ukrainian, that it was something of a Russian enclave inside Ukraine. After all, it had only become part of Soviet Ukraine in 1954, transferred by then premier Nikita Khrushchev from the Russian Federation (for reasons I discussed in a previous article). Crimea’s population at that time was roughly 75% Russian and it was home to the Soviet (now Russian) Black Sea Fleet. But that only tells a small part of Crimea’s story. The peninsula, strategically located at the centre of the Black Sea, was wrested from the Ottoman Empire by Russia in 1783 under Catherine the Great. Its population for centuries had been predominantly Crimean Tatar – a Turkic-speaking, Sunni Muslim ethnic group. In 1944, Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars en masse to Siberia, the Urals and Central Asia and expelled Crimea’s smaller populations Greeks, Armenians and Bulgarians. The peninsula was repopulated with ethnic Russians. Since the collapse of the USSR in 1991, many Crimean Tatars had returned to their homeland, along with other ethnic groups, who were granted citizenship rights by the Ukrainian government.  At least 95 Ukrainians known for their work in the creative industries have been killed since Russia’s full-scale invasion began nearly two years ago, according to the writers’ association PEN Ukraine. The organisation tracks losses among writers, publishers, musicians, artists, photographers, actors, filmmakers, and other creative professionals whose stories appear in the information field. It is likely that many more artists have been killed in the war than appear on PEN’s list. On 7 January the poet Maksym Kryvtsov was killed by artillery fire in Kupiansk, near Kharkiv, one of the key fronts in Moscow’s winter offensive. His loyal companion, a ginger cat, was killed with him. Kryvtsov, aged 33, had been hailed as one of the brightest hopes of Ukraine’s young, creative generation. Kryvtsov was an active participant in the 2013-14 Revolution of Dignity – better known in the West as Euromaidan – and joined Ukraine’s armed forces as a volunteer in 2014, when the war against Russian separatists in the Donbas region began. He was later involved in organisations helping to rehabilitate fellow veterans and help them reintegrate into society, and also worked at a children’s camp. He was, by all accounts, far from the stereotypical image of a fighter. Kryvtsov returned to army in February 2022 when Russian forces invaded Ukraine. Comrades knew him by his call sign Dali – a reference to the curling moustache he grew in imitation of the Spanish artist Salvador Dali. “I think the war is a kind of micellar water that washes cosmetics off: from a face, streets, plans and behaviours. It’s like a hoe cutting through sagebrush, leaving a bitter aftertaste of irreversibility. In war, you become your true self, no need to play a role. You are simply a human, one of billions who ever lived on the Earth, sharing the commonality of breath. There’s no time for love at war. It lies abandoned next to a trash pile and disappears like a grandfather in a fog, lost somewhere behind this summer’s unharvested sunflower fields of a heart,” Kryvtsov said in a 2023 interview with Ukrainian publishing and literary organisation Chytomo as part of its Words and Bullets project with PEN Ukraine. Even through the chaos of war, Kryvtsov continued to write poetry. Many of his poems reflect on the harsh reality of war and the contrast between war and ordinary, civilian life. His first poetry collection Вірші з бійниці (Poems from the Embrasure) was hailed by PEN Ukraine as one of the best books of 2023. Within days of his death, the book’s entire print run had sold out and the reprint had racked up thousands of preorders. Profits from the book will be split between Kryvtsov’s family and projects to bring books to the armed forces. Hundreds of people gathered at St Michael’s monastery in Kyiv to attend a ceremony to honour Kryvtsov, ahead of a funeral in his hometown of Rivne. Some carried copies of his book, others a bouquet of violets, a reference to Kryvtsov’s final poem, posted on Facebook the day before he died (see below). The second part of the memorial service was held in Kyiv’s central Independence Square, the scene of the Euromaidan revolution in which Kryvtsov had participated. Mourners took turns stepping up to a microphone to share their memories of Kryvtsov and his poetry. He “left behind a colossal height of poetry,” said Olena Herasymiuk, a poet, volunteer and combat medic, who was a close friend of Kryvtsov. “He left us not just his poems and testimonies of the era but his most powerful weapon, unique and innate. It’s the kind of weapon that hits not a territory or an enemy but strikes at the human mind and soul.” (quote from the Associated Press) In an outpouring of grief on social media following Kryvtsov’s death, many drew parallels with Ukrainian cultural figures killed during the Soviet Union’s repression of writers and artists in the 1920s and 30s. Among these is the mighty figure of Isaac Babel, whose most famous collection of short stories Red Cavalry was written a century ago, inspired by Babel’s experiences as a war reporter in the Polish-Soviet war of 1920. I have recently been rereading the Red Cavalry stories and had intended my latest article to be about the historical parallels between Babel’s commentaries on war and contemporary war writers in Ukraine. That will have to wait for next time. Instead, I leave you with the prophetic poem Maksym Kryvtsov wrote the day before he died, and an extract from his poem about his ginger cat, posted on Instagram a few days earlier. My head rolls from tree to tree like tumbleweed or a ball from my severed arms violets will sprout in the spring my legs will be torn apart by dogs and cats my blood will paint the world a new red a Pantone human blood red my bones will sink into the earth and form a carcass my shattered gun will rust my poor mate my things and fatigues will find new owners I wish it were spring to finally bloom as a violet My Ginger Tabby When he falls asleep slowly stretches his front legs he dreams of summer dreams of an unscathed brick house dreams of chickens running around the yard dreams of children who treat him to meat pies my helmet slips out of my hands falls on the mud the cat wakes up squints his eyes looks around carefully: yes, they’re his people: and falls asleep again. Taken from Wikipedia, translation credited to Christine Chraibi Russia’s war on Ukraine did not begin on 24 February 2022. Its roots go much deeper, extending back a whole decade, to the last weeks of 2013. Ukraine’s then-president, Viktor Yanukovych had for many months been following a policy of ‘walking towards Europe’. But just at the moment when he was due to sign an agreement with the European Union aimed at forging closer ties, he got cold feet.

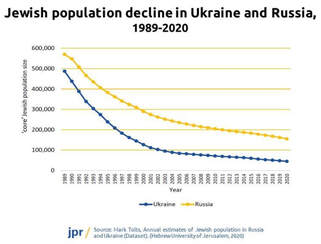

The reason for the about-turn? Vladimir Putin. With promises of cheap gas and advantageous trade arrangements through his new Eurasian union, the Russian president persuaded Yanukovych to turn his back on Europe in favour of deeper ties with Russia. On 21 November 2013, the government announced that it was shelving the EU agreement. Outraged students and young people gathered in Kyiv’s Independence Square, known as the Maidan. They waved EU and Ukrainian flags. They sang Ode to Joy – the anthem of the EU – and Ukraine’s national anthem, with its prophetic opening words: Ukraine has not yet perished. They stayed late into the night and their numbers swelled. By the end of November, their cause seemed lost, the impetus for continuing the protest was waning. But everything changed on the night of 30 November. Riot police stormed the square, firing teargas and beating up the students with truncheons – metal truncheons. Beating them hard enough to break bones. The attack was intended to scare the protestors away and put an end to the demonstrations, but they had precisely the opposite effect. Had Yanukovych not sent his riot police into the Maidan that night with orders to clear the square at any cost, Ukraine could be a very different place today. No full-scale invasion, no Russian republics in the Donbas, no annexation of Crimea. It’s impossible, of course, to turn back the clock to pivotal moments in history and know what would have happened if events had played out differently. My guess is that Ukraine and Russia would have continued to coexist in an uneasy peace, the leadership in Kyiv at times veering towards Europe, then being pulled back towards Moscow. Instead, hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians came out onto the streets in protest at the heavy-handed action of the riot police. The students’ outraged parents joined the demonstrations. Pensioners, mothers with toddlers in pushchairs, tradesmen, ex-soldiers, teachers, doctors – the whole gamut of Ukrainian society rose in outrage. The protest was no longer just about European integration, but about police aggression, corruption, values, morality. In early December, the area around the Maidan transformed into a tent city, a camp of makeshift shelters, complete with a stage and barricades, decorated with flags and banners and slogans. The protestors established kitchens to provide food, medical facilities, book exchanges, donation centres for provisions. They took control of buildings around the Maidan where protestors ate and slept and got respite from the cold. And night after night, they burned tyres and waged war with the riot police. Armed with baseball bats, fireworks and Molotov cocktails, and dressed in balaclavas and bicycle helmets, the anti-government activists pitched themselves against trained squadrons firing tear gas, stun grenades and watercannon. What started as a peaceful student protest within a few weeks had turned into an uprising, a revolution. The nightly clashes reached a climax in February 2014, when police began firing live ammunition. Snipers shot and killed dozens of protestors in a massacre that is still the subject of competing narratives of blame, and whose perpetrators have never been brought to justice. In total 107 activists were killed during the Maidan revolution – nearly half of them during the massacre of 20 February 2014 – and 13 police officers. Today the fallen heroes of what has become known in Ukraine as the Revolution of Dignity are remembered as the Heaven’s Hundred. With Ukraine reeling from the horrors of the massacre, Yanukovych fled, leaving Kyiv in a state of chaos and the country rudderless. Putin was rubbing his hands in glee. Moscow was already widely believed to have infiltrated the Maidan, carrying out ‘false flag’ operations and aiding the government’s forces. As soon as the revolution was over, Putin made his next move: preparations for the annexation of Crimea and violent uprisings in the industrial Donbas regions of Donetsk and Lugansk that would rumble on until the full-scale invasion began, leaving around 14,000 dead and displacing millions of civilians.  Since February 2022, more than six million Ukrainians have fled abroad in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion. Another 8 million are internally displaced, mostly in western Ukraine. And around a million Russians have also escaped abroad, many because of their opposition to the war or to avoid the draft under Russia’s partial mobilisation. Among these numbers are tens of thousands of Jews. According to Israel’s Ministry of Aliyah and Integration, more than 40,000 immigrated to Israel from Ukraine, Russia and Belarus in the year to February 2023. Many members of the Ukrainian Jewish community have also found refuge in other European countries, but those who arrived in Israel held an advantage in having an immediate right to citizenship. The number of Ukrainians with at least one Jewish grandparent – and therefore qualifying for Israeli citizenship by Israel’s Law of Return – was 200,000 in 2020, according to the London-based Institute for Jewish Policy Research (JPR), while the number who identify as Jewish (the ‘core’ Jewish population) was estimated at 45,000. Since the end of the Cold War, the Jewish population of Russia and Ukraine has fallen by 90%, according to the JPR, continuing an exodus that had begun in the early 1970s. An easing of the ban on Jewish refusenik emigration from the Soviet Union at that time allowed approximately 150,000 Soviet Jews to emigrate to Israel. With the collapse of the Soviet Union a further 400,000 departed, with more than 80% heading to Israel and the remainder mostly to Germany and the US – several members of my own family among them. In 2014, the number of Ukrainian Jews immigrating to Israel jumped by 190% in response to Russia’s annexation of Crimea and occupation of parts of eastern Ukraine. Jewish emigration from Russia also spiked and the numbers coming to Israel from both countries stabilised at this higher level in the eight years leading up to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. With another war now raging in the Middle East, some of those displaced by the hostilities in Ukraine have had to flee twice over. Among them are more than sixty children from the Alumim children’s home near Zhytomyr in western Ukraine. Some are orphans from the surrounding towns and villages within the historic Pale of Settlement, others have parents who are unable to provide a stable home for them. On 24 February 2022, bombs began to fall around the home, which was located close to a Ukrainian air base. Its founders, Rabbi Zalman Bukiet and his wife Malki, had made advance preparations in case of a Russian attack and were able to quickly evacuate the children to the west of the country by bus. After a few days, when it became clear that the war would not reach a swift conclusion, they crossed the border into Romania and from there boarded a plane to Israel. The logistics of the transfer were complex as almost none of the children had passports. Some of their mothers and other community members joined the group until it numbered 170 people. “El Al Airlines wanted us to finalise the number of seats we needed, and the paperwork was an open question,” Rabbi Bukiet recalled. One child had been away visiting his home village when the war broke out and had to be driven to Romania by taxi for a fare ten times higher than the standard rate. Once in Israel, the group was hosted at the Nes Harim education centre in the Jerusalem Hills. “We came for a month and stayed for six,” Rabbi Bukiet said. But as the new school year came round, he needed to find a more permanent home for the children. The group moved to Ashkelon, a coastal town in southern Israel, and rented two accommodation buildings – one for girls and one for boys – as well as apartments for the 16 families that had come with them from Zhytomyr and a home for the rabbi and his own family. “And so Ashkelon became home. The kids learned Hebrew, gained Israeli friends and integrated into the local community. The mothers took jobs and learned to navigate life in Israel. And we all got used to the new normal,” Rabbi Bukiet said. He and Malki arranged visits for a family member from Ukraine for each child, along with outings and activities. With the next school year due to begin, the group decided to stay another year in Ashkelon. Until history repeated itself. On 7 October the sirens once again blared at six am, just as they had in Zhytomyr 18 months or so earlier. Once again, the sound of gunfire and explosions reverberated around them. Rabbi Bukiet and his own family ran to a shelter but were unable to reach the children’s dormitories until midday. By the afternoon, the constant sirens had eased the he and Malki were able to gather the children together in a larger shelter. That night they made plans to relocate again, further north into Israel. Today the inhabitants of the children’s home are based in the Hasidic village of Kfar Chabad, not knowing how long they will stay. Safe for now, their future is uncertain once again. The full story of the Alumim children's home can be found here: https://www.chabad.org/library/article_cdo/aid/6186434/jewish/How-Our-Childrens-Home-in-Ukraine-Was-Uprooted-Again-by-War-in-Israel.htm  When Hamas terrorists entered southern Israel last month, they committed the biggest mass murder of Jews since the Holocaust. That on its own is a desperately chilling thought. But Israel’s response to the attacks has unleashed a wave of antisemitism around the globe on a scale not seen since the middle of the last century. Words that for decades have been unsayable in public are now being chanted in the streets of our major cities. And in Russia, a country with a devastating history of antisemitism that had until recently been quashed, pogroms have broken out once again. Throughout the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Jews in Russia suffered wave after wave of pogroms – anti-Jewish riots that involved terrorising communities, attacking Jewish homes and businesses, humiliating and maiming, rape and murder. Last weekend Russia witnessed its first pogrom in sixty years. In Dagestan, a mainly Muslim region of southern Russia bordering Chechnya, an angry mob shouting antisemitic slogans stormed the airport of the regional capital Makhachkala. The rioters broke through security barriers onto the runway with the intention of attacking passengers arriving from Tel Aviv, fuelled by rumours circulating on social media that the plane was carrying refugees from Israel. The rumours were later proven to be untrue. Elsewhere in Dagestan, a riot broke out outside a hotel in the city of Khasavyurt, because Israeli refugees were believed to be sheltering inside. The protestors pinned a sign to the door: Entry strictly forbidden to Israelis (Jews). And in Nalchik - located, like Dagestan, in the North Caucasus region - a mob attacked and set alight a Jewish cultural centre that was under construction. The words Death to Jews were daubed on its wall. These events took place in spite of strict rules prohibiting public demonstrations in Russia, implemented to stifle protest against the war in Ukraine. The pogroms of the past took place across the Pale of Settlement, where Jews were restricted to living in Tsarist times – in present day Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and the western fringes of Russia. These regions had been absorbed by Russia during the partitions of Poland under Catherine the Great in the late 18th century. Jews had long been present in great numbers in Poland because its liberal policies contrasted with most other parts of Europe at the time; Jews were welcomed for their skills in commerce that helped bolster the economy. But Russia was far less tolerant and pogroms were a direct result of an official policy of antisemitism. Today’s pogroms in Dagestan derive from sympathy with Palestinians under Israeli bombardment in Gaza. With a mostly Muslim population, Dagestan has historically been more closely aligned with the Middle East than with Russia. But it is also home to Russia’s oldest Jewish community. Jews have lived in the region since Biblical times and as Jews from elsewhere in Russia have emigrated in huge numbers, mostly to North America and Israel, Dagestan today is home to Russia’s largest Jewish community. Just as the pogroms of the past were a manifestation of official antisemitism in the Russian Empire, the pogroms in Dagestan reflect a change in sentiment in the echelons of power in Moscow. While the Vladimir Putin of the past spoke out against holocaust denial and xenophobia, the Russian president has in recent months ratcheted up antisemitic rhetoric as a reaction to Russia’s failings in the war in Ukraine, not least with his derogatory comments about Ukraine’s Jewish president Volodymyr Zelensky (see my article on the subject here). Putin’s reaction to the violence in Dagestan has been to blame Ukraine and the West, accusing Russia’s enemies of fomenting unrest to destabilise the country. The violence in Dagestan continues a worrying trend for Putin, demonstrating again how his authority is being undermined. Having risen to power almost a quarter of a century ago, Putin cemented his popularity with a reputation for restoring Russia’s territorial integrity and stability after the chaotic unravelling of the 1990s. It was his quelling of violence in Dagestan and neighbouring Chechnya that helped reinforce the strongman image that the president has sought to project ever since. But Putin’s obsessive focus on trying to destroy Ukraine has led him to turn a blind eye to unrest in Russia’s provinces that threatens to undermine his reputation and the sense of order and stability that he has so painstakingly nurtured. The attempted mutiny in June by his once loyal ally Yevgeny Prigozhin was the first clear manifestation of Putin’s authority beginning to unravel. Unrest in the North Caucasus may be the next. |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed