Anyone who has followed my blog will know that I have written extensively about pogroms. My family survived pogroms and I have been writing about them for years. But I never expected to witness pogroms in my lifetime. The slaughter of communities in southern Israel by Hamas terrorists is a stark reminder of the antisemitic violence our ancestors faced repeatedly in the Russian Empire more than a century ago: brutal assaults, rape, beheadings, indiscriminate killing of women, children and babies, entire families massacred. The Hamas attacks were also timed to call to mind the shock invasion of Israel in 1973 by Syrian and Egyptian forces, which took place on Yom Kippur, the holiest day in the Jewish calendar. This month’s surprise invasion by Hamas coincided with the end of Sukkot, again a time when Jews were celebrating a religious holiday, and exactly fifty years on from the Yom Kippur war. Back in 1973, the Arab forces were armed by the Soviet Union and were quickly and soundly defeated by Israel and its ally, the US. Today, neither Israel nor Gaza is likely to win a rapid or decisive victory. Ironically, the only probable winner in the conflict will be the Soviet Union’s dominant successor state – Russia. Israeli images of burnt-out cars, bodies littering the streets, houses and shops pockmarked with bullet holes, are hauntingly reminiscent of the scenes in Ukrainian towns including Bucha and Irpin in March 2022 after Russia’s failed attempt to take Kyiv. While there is no evidence to suggest that Russia was directly involved in the Hamas incursions, Russian weaponry has almost certainly found its way to Gaza – provided by Iran – and may well have been used by the Palestinian fighters. Russia’s relations with Hamas date back to 2006, when the Palestinian faction won its famous election victory. Numerous Hamas delegations have visited Moscow since then, most recently in March this year, as Russia has attempted to carve out a niche for itself in the Middle East peace process by mediating between different Palestinian groups. Russia’s relationship with Iran – Hamas’ main international backer – has strengthened considerably in the last 18 months as Moscow has become heavily dependent on Tehran as a supplier of weapons, including artillery and tank rounds and, most importantly, the Shahed kamikaze drones that it uses to attack civilian infrastructure in Ukraine. For Russia, the key benefit of the conflict in Israel and Gaza is that it is diverting the West’s attention away from Ukraine. For the first time in 18 months, the spotlight is no longer on Moscow’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, and US President Joe Biden has promised to supply Israel with all the military assistance it needs. If the violence in the Middle East continues for more than a few weeks, this is likely to engender a fall in US financial and military support for Ukraine. “Russia is interested in triggering a war in the Middle East, so that a new source of pain and suffering could undermine world unity, increase discord and contradictions, and thus help Russia destroy freedom in Europe,” Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky said this week. Russia’s response to the events in the Middle East has been muted, in spite of its strengthening ties with Israel, forged by the countries’ cooperation over Syria that has enabled Israel to secure its north-eastern border. For Kyiv, the timing of the latest Middle East crisis is terrible, coming just when the tide appears to be turning against Ukraine. Its ground offensive has been slower and less successful than had been hoped, the army is running out of ammunition, and international support is waning. Even before the Hamas attacks, some US Republicans were arguing against continued military aid for Ukraine, and with a tight presidential election campaign looming, many fear that US weapons supplies will tail off. While Israel is a longstanding ally of the US and holds great resonance for many Americans, Ukraine is often perceived as distant and irrelevant to US interests. If the two are in competition for US funding, Israel will be the winner. Elsewhere, Slovakia recently elected a government that is sympathetic towards Russia, breaking the EU’s consensus of support for Ukraine. And in Poland, where voters go to the polls this weekend, a far-right coalition campaigning to reduce support for Ukraine and Ukrainian refugees may end up holding the balance of power. Already disputes over Ukrainian grain exports being diverted through Poland have cooled relations between the countries. Zelensky is keen to draw parallels between the two conflicts, to urge the West to support the cause of democracy, freedom and human rights. “It’s the same evil – the only difference is that it was a terrorist organisation that attacked Israel, and here a terrorist state attacked Ukraine,” he says. Support for Israel is palpable in Ukraine as the population sees those parallels too. A large screen in Kyiv is lit up with an image of the Israeli flag and locals have placed flowers and candles outside the Israeli embassy. The visible signs of support come in spite of Israel’s lack of military aid and its repeated refusal to make its Iron Dome missile defence system available to Ukraine, as well as arguments over Israel’s treatment of Ukrainians refugees.

0 Comments

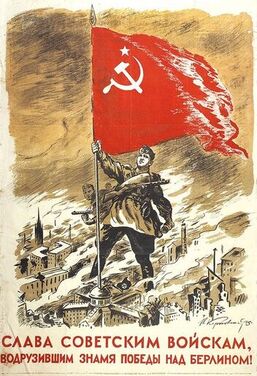

Vladimir Putin has been accused of multiple crimes and offences over the years, but until recently, antisemitism wasn’t one of them. In the last few months, he has come in for criticism from the West, from Israel and the Ukrainian leadership for a spate of antisemitic comments. Putin appeared on TV in early September ranting that “Western masters” installed Volodymyr Zelensky, “an ethnic Jew, with Jewish roots, with Jewish origins” as Ukraine’s president “to cover up the anti-human essence that is the foundation…of the modern Ukrainian state” and “the glorification of Nazism.” The diatribe followed comments made at the St Petersburg international economic forum in in June, when Putin was asked about the apparent contradiction of Ukraine being a Nazi state led by a Jew. “I have a lot of Jewish friends. They say Zelensky is not a Jew; he is a disgrace to the Jewish people,” he said. And most recently, speaking at an economic forum in Vladivostok, Putin said of the former senior Kremlin official Anatoly Chubais, who fled Russia after last year’s invasion of Ukraine and is reportedly living in Israel, “He is no longer Anatoly Borisovich Chubais, he is some sort of Moishe Israelievich, or some such.” The brand of ethnic nationalism that Putin has started to espouse sits rather strangely. Firstly, there’s that awkward issue in his repeated claims to be trying to “denazify” Ukraine, that the country’s leader is a Jew who lost several members of his family in the Holocaust. To those raised with a Soviet (or post-Soviet) view of history, this is less paradoxical than it seems. According to Soviet historiography, no specific emphasis was placed on the Nazis’ persecution of Jews, rather the focus was on the suffering of the Soviet people as a whole. And indeed, the suffering of the Soviet people was terrible, Hitler’s regime classed Slavs as sub-human and Communists were a mortal enemy. There was little awareness during Soviet times that the Jews had suffered any more than the rest of the population and many Russians have held onto that mindset. Putin’s antisemitic outpourings echo comments made in May last year by his foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov, comparing Zelensky with Hitler. Lavrov claimed that Jews had been partly responsible for their own murder by the Nazis because, “some of the worst antisemites are Jews,” and Hitler himself had Jewish blood. But the conflation of Zelensky and Nazism doesn’t fully explain Putin’s recent antisemitic outbursts. According to historian Artem Efimov, Editor-in-chief of Russian independent media outlet Meduza’s Signal newsletter, the Russian president is exploiting rhetoric to serve his purpose, whether that rhetoric is Marxist, right-wing or, indeed, antisemitic. His words are not based on any deep, systematic beliefs – for Putin has no ideology of his own – but serve as a means to justify his actions, Efimov says. Most notably, Putin repeatedly manipulates the collective memory of Russia’s struggle against Nazism in World War II – or the Great Patriotic War as it is known in Russia – to legitimise his imperialist ambitions in Ukraine. In pivoting towards antisemitism, Putin is repeating an age-old tendency to create a distraction, a scapegoat even, as his strongman image frays and begins to fall apart. As I have written before, Putin has more than a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him. Stalin, amid the paranoia and insecurity that characterised the final years of his rule, repeatedly resorted to antisemitism to push the blame onto others. The post-war years were characterised by Stalin’s purge of “rootless cosmopolitans”, a reference largely to Jews, whose loyalty to the USSR was questioned with the formation of the state of Israel in 1948. Well-known members of the Jewish Anti-fascist Committee, formed during the war to organise international support for the Soviet military effort, were arrested, tortured, and executed. Shortly before his death in 1953, Stalin launched another anti-Semitic purge in the form of the “Doctor’s Plot” – an alleged conspiracy by a group of mostly Jewish doctors to murder leading Communist Party officials. The plot was thought to be a precursor to another major purge of the party, and was halted only by Stalin’s death. Moscow’s former chief rabbi, Pinchas Goldschmidt, has repeatedly warned of rising antisemitism in Russia and urged Russian Jews to leave the country while they still can. Rabbi Goldschmidt resigned in July 2022 because of his opposition to the war and lives in exile in Israel. Tens of thousands of Russian Jews have already emigrated to Israel since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine began in February last year, the largest wave of departures since the fall of the Soviet Union.  Ukraine doesn’t rank high on the holiday bucket list for most of us right now. But thousands of Hassidic Jews have ignored warnings about travelling to a war zone and flocked to the small town of Uman, some three hours south of Kyiv, for an annual new year pilgrimage. They came to worship at the grave of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov who was buried in Uman in 1810. Not all are religious Jews, for according to tradition, the rabbi promised to intercede on behalf of anybody praying at his grave on Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish new year. This year around 35,000 pilgrims arrived in Uman (up from the 23,000 who visited last year) in spite of warnings from the Ukrainian and Israeli authorities not to travel because of the risk of Russian air attacks and insufficient bomb shelters for the influx of visitors. Some brought young children with them, believing that a child who visits the grave site before the age of seven will grow up to be without sin. A small number of pilgrims have even been known to bring newborn babies to be circumcised in Uman, in spite of a lack of medical facilities for the procedure in Ukraine. Visitor numbers are only slightly down on the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion, even though Uman has been targeted on several occasions. In April more than 20 missiles struck the town killing 24 people including several children in a residential district. It last came under Russian missile attack in June. The front line lies around 200 miles to the south. “It is very dangerous. People need to know that they are putting themselves at risk. Too much Jewish blood has already been spilled in Europe. How can you take such a risk?” Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu said earlier this month. With Ukrainian airspace closed, the journey to Uman is long, costly and uncomfortable, involving a flight to Poland, trains, minivan taxis and an inevitable long wait at the border. But the pilgrims remain undeterred in spite of the danger, expense and logistics of holidaying in a war zone. Some are firm in the belief that their Rabbi will protect them from beyond the grave; others just come to party and have a good time. Most come from Israel and spend up to a week in Uman around Rosh Hashanah. Although women are allowed on the pilgrimage, the vast majority of the visitors are men. The annual Jewish gathering has become the town’s major source of income, with pilgrims charged a $200 fee to visit. In recent years, the rabbi’s grave has been renovated with funds donated by Jewish tycoons from around the world. Hotels and hostels have popped up and locals have carried out house renovations to provide accommodation priced at hundreds of dollars a night. Those who can’t afford the exorbitant room prices pitch tents in courtyards or vacant lots. A whole hospitality industry has built up around the pilgrims, offering kosher food and drink at vastly inflated prices, using Hebrew signage and accepting payment in dollars or Israeli shekels. Most of the business owners are Israelis. Dozens of Israeli families moved to Uman in the years before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The annual influx of bearded, black-robed, skull-capped men makes quite an impact in this quiet town. While the visitors provide Uman with much-needed cash, relations between the pilgrims and the townsfolk are not always harmonious. Locals complain about the loud music, drunkenness, fighting and excessive litter. They resent the police cordons and checkpoints that prevent them from going about their daily business; and they question how the authorities are spending the money collected from the pilgrims, citing widespread corruption. Imagine a massive rave – albeit a religious one – taking over the streets of a small, unexceptional town and you start to get the picture. The Hassidic music blasting from speakers in the streets is imbued with a techno twist. Alcohol and drugs are much in evidence, as is prostitution. It’s hard to put a number on the percentage who come to celebrate and party, not just to pray. There’s a heavy security presence, even in peacetime, but it was stepped up this year in light of the added dangers of war. Police numbers have increased since 2010, when a young Israeli was stabbed in a brawl and ten pilgrims were deported after violent clashes broke out. Violence in Uman is nothing new. In 1941, under German occupation, the Nazis murdered 17,000 Jews here and destroyed the Jewish cemetery, including the grave of Rabbi Nachman, which was later located and moved before the area was redeveloped for housing. The original burial site was close to a mass grave for victims of another Jewish massacre, one that took place in 1768 as part of the Haidamak uprisings. The Uman pilgrimage began shortly after the rabbi’s death in the early 19th century and attracted hundreds of Hassidic Jews from Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland until the Russian Revolution of 1917 closed the borders. The photo below dates from this period. In spite of the Communist regime’s clampdown on religious practice, a trickle of pilgrims continued to visit the grave site, including some Soviet Jews who made the journey in secret and were exiled to Siberia as a consequence. From the 1960s, small numbers of American and Israeli Jews travelled to Uman either legally or clandestinely. In the late 1980s, travel to the Soviet Union became easier and the number of pilgrims began to grow. Around 2,000 made the journey to Uman in 1990, rising to 25,000 by 2018.  Warsaw is possibly the most fascinating city I have ever visited. Its glorious old market square, lined with Baroque-style merchants’ houses, rivals those of Krakow, Prague or Brussels. And yet Warsaw’s old town was reconstructed from scratch in the middle of the twentieth century. Somehow the knowledge that the colourful facades are mere decades rather than centuries old added to my appreciation of them – each one painstakingly rebuilt using 18th century paintings of the city by the Venetian artist Bernardo Bellotto as a blueprint. That this reconstruction was carried out during a period when Stalinist architecture dominated in the Soviet bloc makes it doubly remarkable. The rebuilding of Warsaw itself could, in the coming years, serve as a blueprint of another kind – as a route-map for the reconstruction of Ukrainian towns and cities after months of Russian aerial bombardment. While much of Europe experienced destruction on a monumental scale during World War II, the fate of the Polish capital was uniquely cruel. Most of the city was razed to the ground in retribution for the failed Warsaw Uprising of August-September 1944, when the Polish resistance attempted to liberate the city from Nazi occupation. Despite being poorly equipped, the Poles succeeded in killing or wounding several thousand German fighters in a battle lasting for two months, but at a terrible cost. Up to 200,000 Polish civilians were killed, mostly in mass executions, and once the Germans had quelled the uprising, they systematically destroyed what remained of the city, reducing more than 85% of its historic old town to ruins. Today we can only imagine how daunting the task of reconstruction must have seemed. Indeed, some suggested at the time that what remained of Warsaw should be left as a memorial and the capital relocated elsewhere. Many residents and refugees, who returned once Soviet and Allied forces reoccupied the ruined city, were formed into work brigades tasked with clearing the vast amounts of debris, as were German prisoners of war. It was estimated that the sheer volume of rubble – around 22 million cubic metres of the stuff covering almost the entire city – meant that it would take 20 years to transport it out of the city by daily goods trains. Amid the post-war scarcity, Poland lacked the financial resources to purchase construction materials. And the hundreds of brickworks that had flourished in Warsaw before the war – many of them owned by Jews – no longer existed. If the city was to rise from the ashes, the only option was to reuse the rubble from former buildings to rebuild anew, and a host of new construction techniques were invented to fashion new building materials from old. The Polish word Zgruzowstanie came into use to refer to this post-war innovation in recycling building materials. It was also the name of a recent exhibition at the Museum of Warsaw about the city’s reconstruction, translated into English as Rising from Rubble. The exhibition was curated by architectural historian Adam Przywara, based on his PhD research about the new technological developments that emerged during Warsaw’s post-war reconstruction. The most important of these was gruzobeton, or rubble-concrete – a mix of crushed rubble, concrete and water, which was formed into breeze-blocks and became one of the main symbols of post-war Warsaw. Innovative methods were used to reconstitute old bricks and use them in new buildings. Rubble from the former ghetto was formed into building materials and used to build new neighbourhoods. Salvaged architectural details from demolished buildings in the old town were added to the reconstructed facades. Iron was recovered and reused. Mass demolitions even took place in other Polish cities, including Wrocław and Szczecin, to provide more bricks to rebuild Warsaw. Rubble that could not be used in construction was piled up in huge mounds to form geographical features including the Warsaw Uprising Mound, Moczydłowska hill and Szczęśliwicka hill. Although the old town was – remarkably – largely rebuilt by 1955, reconstruction elsewhere in the city lasted until the 1980s, and rubble became a national symbol used by the communist regime to represent the collective effort of reconstruction and a brighter, socialist future. The Rising from Rubble exhibition is more than just a lesson in history. “There are two areas of contemporary relevance: the idea of sustainable architecture, and how it might relate to rebuilding in Ukraine,” Przywara is quoted in The Guardian. Today Warsaw is home to hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian refugees and is a key transit point for travel to and from Ukraine. Numerous Ukrainian and European delegations, architects and city planners have passed through and made a point of visiting the exhibition, taking Przywara’s point that the city’s post-war reconstruction could become a blueprint for rebuilding Ukraine’s urban landscapes. The mayor of Mariupol was one such visitor, and the parallels between last year’s Russian air strikes on Mariupol and the bombing of Warsaw nearly 80 years earlier are plain for all to see.  Ever since Yevgeny Prigozhin staged his failed mutiny two months ago, commentators in the West have been suggesting that he should avoid standing near windows in tall buildings and keep an eye on who serves his tea, not to mention who washes his underpants – references to the Kremlin’s favoured methods of disposing of its critics in recent months. When Prigozhin’s plane crashed yesterday near Tver, while travelling between Moscow and St Petersburg, the only surprise was the means of death. At the time of writing, it remains unclear whether the crash was caused by a bomb on board the plane, or whether the aircraft was shot down. Either scenario would implicitly require the authorisation of Russia’s top brass. After years of political assassinations in which Vladimir Putin has denied, shrugged off, or indeed scoffed at, any involvement by the Kremlin, this one could be hard for him to rebuff – although his former advisor Sergei Markov has already attempted to pin the blame on Ukraine. Putin has repeatedly imprisoned, poisoned, shot or defenestrated his political rivals, but the demise of Prigozhin (assuming that he was indeed on the downed plane) marks the first assassination of one of the president’s inner circle. Prigozhin was a former convict who emerged from prison in 1990 to sell hotdogs from a street stall in St Petersburg before expanding into the restaurant business and becoming chief caterer to the Kremlin, earning himself the sobriquet Putin’s Chef. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 provided the springboard for Prigozhin’s involvement in the military, including major contracts for food and supplies to the Russian army and establishing a band of mercenary soldiers, who have been accused of numerous war crimes in Syria and, of course, more recently in Ukraine. But Prigozhin’s troops fought not only on the battlefield – they have also been mired in allegations of creating a network of fake online accounts to interfere in the US presidential election in 2016. I have written before that Putin has more than a whiff of Joseph Stalin about him, and his (assumed) purging of Prigozhin is yet another reminder of the Soviet past. No member of Stalin’s entourage was ever safe. One whispered word or false rumour of criticism of the leader was enough to prompt a show trial, a forced confession and a bullet in the back of the head. It’s 70 years since Stalin died and – thanks to Putin – his reputation today is being rehabilitated as never before since his denunciation by his successor, Nikita Khrushchev, in the so-called Secret Speech of 1956, when Stalin’s crimes were made public for the first time. Hundreds of modern-day Stalinists gathered in Moscow’s Red Square in March to mark the anniversary of his death, and the state-run news agency RIA Novosti published an article with the headline “Stalin is a weapon in the battle between Russia and the West”, which argued that criticising Stalin is “not just anti-Soviet but is also Russophobic, aimed at dividing and defeating Russia”. It was Stalin who led the Soviet Union through the devastation of World War II. Putin’s rhetoric during his full-scale military invasion of Ukraine harks back repeatedly to the Great Patriotic War, as it is known locally. He equates the war in Ukraine with the fight against Nazi Germany, Ukrainians with fascists. Famously, Putin has stated that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century, and he has tirelessly aimed his foreign policy at recreating the Soviet era, trying to reimpose control over the former republics as well as attempting to restore Russian ascendancy on the world stage. He brought back the Soviet national anthem and Soviet-era symbols, endeavouring to put back the jigsaw pieces of the past, but making a different shape – one representing the dollar sign rather than the hammer and sickle, with Capitalist bling replacing Communist drudgery. That Communist drudgery came to an end exactly 32 years ago following a previous attempted coup, one used by many commentators to draw parallels with the past during Prigozhin’s mutiny in June. In late August 1991 a group of die-hard Communists, opposed to the reform agenda of President Mikhail Gorbachev and his loss of control over the Soviet republics and former Eastern European vassal states, attempted to seize power. Although the coup failed, it prompted the immediate collapse of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and, just four months later, the whole country. Ironically, the attempted coup aimed at preserving the Soviet empire precipitated Ukraine’s declaration of independence on 24 August the same year, an anniversary it is marking today without parades or public celebrations out of fear that such events would be targeted by Russian air strikes. Instead, Ukraine is marking the anniversary with a public holiday and a kilometre-long display of destroyed Russian military vehicles on Khreshchatyk, Kyiv’s central boulevard.  War crimes come in many guises – from the shocking acts of violence in Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine in the early weeks of the war to the missile attacks on hospitals and schools, to last month’s destruction of the Kakhovka dam that led to flooding and environmental damage on a colossal scale. But the only war crime that the International Criminal Court (ICC) has so far charged Russian president Vladimir Putin with is the forced abduction of Ukrainian children to Russia. The Financial Times has reported that Saudi Arabia and Turkey are attempting to broker a deal to return thousands of Ukrainian children currently being held in children’s homes in Russia or adopted by Russian families. Nearly 20,000 children have been abducted to Russia, according to Ukrainian sources, although Russia claims the number is far lower. So far about 370 of these children have managed to return to Ukraine, but the process is made painfully difficult. Although Moscow says it will allow children to leave if a legal guardian can collect them, a child’s parent or relative must reclaim them in person and appeal to the local social services for their release. This entails a long and convoluted journey to Russia via Poland and Belarus or the Baltic states, because direct border crossings no longer operate. From Russia, some must continue to Crimea to find their children. But many families whose children have been abducted still live in dangerous regions of Ukraine precisely because they lack the money and passports to enable them to leave, making it harder still for them to make the journey to Russia. In spite of the ICC arrest warrant issued in March against Putin and his children’s rights commissioner Maria Lvova-Belova, the abductions have continued. Some children are taken by pro-Russian relatives or friends, sometimes for financial reasons. Cases have been documented in which foster parents have quickly become abusive once a child is in Russia and used the money they receive for fostering to buy alcohol. Others are kidnapped when their orphanage or boarding school is relocated to Russia from Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine. Many children have been separated from their parents when front lines have shifted while they are away at summer camp, leaving them under Russian occupation, and at risk of relocation to Russia, while their parents remain in Ukrainian-held territory. Earlier in the war, several children whose parents were killed during the siege of Mariupol were forcibly taken to Russia. In addition to the thousands of children abducted to Russia, The Telegraph reported this week that more than 2,000 Ukrainian children have been taken to Belarus since last September on the orders of President Aleksandr Lukashenko. These children are mostly from Russian-occupied areas of Eastern Ukraine. They are taken to Rostov-on-Don, a Russian city some two hours from the border, before being transferred by train to the Belarusian capital Minsk, then bussed to at least four different children’s camps. These camps follow the same pattern as those in Russia. Ukrainian children are subjected to a process of brainwashing to Russify them and eliminate their sense of Ukrainian identity. They sing the Russian national anthem, chant “Down with Ukraine!”, and study lessons according to a Russian curriculum. They learn how Russia is a great country; that the Russian motherland will protect them; that Ukraine has never been a nation and Kyiv will be obliterated. Teenagers are sometimes taken to shooting ranges and taught how to fire machine guns – weapons that they may later use against their fellow Ukrainians. Russia’s brainwashing of Ukrainian children is nothing new. The Ukrainian novelist Victoria Amelina wrote in her essay Expanding the Boundaries of Home: a Story for us All, published by the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in April, about her upbringing as a Russian-speaking Ukrainian in Lviv. “I was born in western Ukraine in 1986, the year the Chornobyl nuclear reactor exploded and the Soviet Union began to crumble. Despite my birthplace and the timing of my birth, I was educated to be Russian. There was an entire system in place that aimed to make me believe that Moscow, not Kyiv, was the center of my universe. I attended a Russian school, performed in a school theater named after the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin, and prayed in the Russian Orthodox church. I even enjoyed a summer camp for teenagers in Russia and attended youth gatherings at the Russian cultural center in Lviv, where we sang so-called Russian rock music.” Victoria grew up reading the Russian classics, watching Russian TV, and was chosen to represent Lviv at an international Russian language competition in Moscow at the age of 15. “The Russian Federation invested a lot of money in raising children like us from the "former Soviet republics" as Russians. They probably invested more in us than they did in the education of children in rural Russia: those who were already conquered didn't need to be tempted with summer camps and excursions to the Red Square.” She recounted how a famous Russian journalist interviewed her 15-year-old self for the evening news during her trip to Moscow. After a polite question about her initial impressions, the journalist swiftly switched to grilling her on the oppression of Russian speakers in Ukraine. In a split second, she realised that the entire purpose of the interview was to reinforce a false Russian narrative. After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Victoria recalled the story of her trip to Moscow, and her conversation with the Russian journalist, when she watched a TV interview with an older man from Mariupol: “He was desperate, disoriented, and remarkably sincere. "But I believed in this Russian world, can you imagine? All my life I believed we were brothers!" the poor man exclaimed, surrounded by the ruins of his beloved city. It must be way more painful to realize where your true home is in such a cruel way, and so late in life. The man's apartment building was in ruins, and the illusion of home, the space he perceived as his motherland, the former Soviet Union where he was born and lived his best years, had been crushed even more brutally. The propaganda stopped working on him only when the Russian bombs fell.” Victoria Amelina put aside her fiction writing following the Russian invasion and became a war crimes investigator. She travelled to areas of Ukraine that had been liberated from Russian occupation and interviewed witnesses and survivors of Russian atrocities. On her final trip to Eastern Ukraine, Victoria was killed after a missile strike on the pizza restaurant in Krematorsk where she and the group of foreign writers she was accompanying were having dinner. She died on 1 July 2023, aged 37. Click here to read Victoria Amelina’s essay in full. A month has passed since the collapse of the Kakhovka dam in southern Ukraine caused one of the world’s most devastating environmental catastrophes of recent years. The images will live long in the memory – floodwater lapping at the rooftops of Kherson, while civilians attempting to flee their homes in rubber dinghies are targeted by Russian shelling. A video of Ukraine’s chief rabbi, Moshe Reuven Azman, diving for cover as he comes under fire from Russian snipers has been viewed more than a million times. Ukrainian officials say over 100 people died following the dam’s collapse on 6 June as the water hurtled downstream. Today the floodwaters have receded from Kherson and water levels are almost back to normal, but what remains is a sea of mud. Residents have returned and are busy clearing the streets and attempting to renovate their homes, which emit odours of damp and mould. People say they are grateful the disaster happened at the beginning of summer, so that their homes have time to dry out before the winter. The city centre still comes under daily shelling from across the river. The floods are yet another tragedy that the residents of Kherson have had to bear. The city has suffered more than almost anywhere else in the course of 16 months of war – occupied in the early days, the people terrorised and unable to escape, then incessantly bombarded with artillery and rocket fire from across the River Dnieper since the Russian withdrawal last November, deprived of drinking water and electricity. Outside the city, in lower-lying areas below the dam, huge lakes remain in places where there was no water before. The floods destroyed villages, farmland and nature reserves. Crops were lost across vast swathes of farmland as the floodwater raced through, taking with it pollutants including oil and agricultural chemicals, which all gushed into the Black Sea. Further west, residents of Mykolaiv have been warned not to drink tap water, go swimming or catch fish after Cholera-like bacteria were detected in the water. Odesa’s once beautiful coastline has transformed into “a garbage dump and animal cemetery,” according to Ukrainian officials. Of even greater concern are the regions upstream of the dam, where the vast reservoir lies almost empty, changing the entire ecosystem. Half a million people have had their drinking water supply cut off and businesses, agriculture and wildlife have all suffered a massive impact. Covering more than 2,000 square kilometres, the reservoir spanned the Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and Dnipropetrovsk districts, and was known by locals as the Kakhovka Sea because it was so big that they could not see the opposite side. Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky described the dam’s collapse as “an environmental bomb of mass destruction”. Kyiv and Moscow have blamed each other for the dam’s destruction. Ukraine is investigating the event as a war crime and possible ecocide, and estimates the cost of remedying the destruction at 1.2 billion euros. Preliminary findings from a team of international legal experts working with the Ukrainian prosecutors indicate that it was “highly likely” that the dam’s collapse was triggered by explosives planted by the Russians. Evidence documented by the New York Times also suggests that an explosion in the dam’s concrete base detonated by Russia is the likely cause. The Soviet-era dam has been under Russian control since the early stages of the war last year. Russia’s motivations for such an attack are manifold. Not only would it disrupt and potentially stall Ukraine’s advances and undermine the narrative of its counter-offensive, but also cut hydroelectric power and water supplies, divert resources and potentially help erode the will of the Ukrainian people to resist. But Russia accuses Kyiv of sabotaging the hydroelectric dam to cut off a key water source for Crimea and detract attention from the slow progress of the counter-offensive. Last week, Swedish eco-activist Greta Thunberg was in Ukraine to meet Zelensky and other members of a new environmental group tasked with assessing the environmental damage resulting from the war. She reiterated Ukraine’s use of the word ‘ecocide’ to describe the ecological disaster brought about by the collapse of the dam. But the flooding is not the only environmental impact of the war. About 30 percent of Ukraine’s territory is contaminated with landmines and explosives, and more than 2.4 million hectares of forests have been damaged, Ukraine’s prosecutor general Andriy Kostin says. There has been a long-running battle to get large-scale environmental destruction recognised as an international crime that can be prosecuted at the International Criminal Court (ICC) and the unfolding ecological disaster in Ukraine may bring that a step closer. In 2021 a panel of experts that included the lawyer and author Philippe Sands drafted legislation – yet to be adopted – to enable the ICC to prosecute ecocide, in addition to its existing remit of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and the crime of aggression. A team from the ICC has visited the area affected by the flooding to investigate.  Eighty years ago, the biggest Jewish revolt against Nazi aggression was under way. The Warsaw ghetto uprising, which lasted from 19 April-16 May 1943, was an attempt to prevent the deportation of the remaining population of the ghetto to the gas chambers. The previous summer, more than a quarter of a million Jews had been transported from the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka. Foreseeing their own fate, the remaining residents developed resistance movements, smuggled weapons into the ghetto and prepared to fight. They knew that victory was impossible; they fought instead for the honour of the Jewish people, and to prevent the Germans from choosing the time and place of their deaths. On 19 April 1943, the eve of Passover, Germans entering the ghetto to begin the deportation were met by gunfire, grenades and Molotov cocktails. Pitched battles raged for days, until the Germans resorted to burning down the ghetto, block by block. Thousands of Jews took refuge in sewers and bunkers, which the Nazis then destroyed. The uprising came to an end on 16 May 1943. Around 13,000 Jews had died, and a further 55,000 were captured and taken to the death camps at Treblinka and Majdanek. The presidents of Germany, Poland and Israel gathered on 19 April at a memorial on the site of the former ghetto to mark the 80th anniversary of the uprising. “I stand before you today and ask for forgiveness,” German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier said. “The appalling crimes that Germans committed here fill me with deep shame… You in Poland, you in Israel, you know from your history that freedom and independence must be fought for and defended, but we Germans have also learned the lessons of our history. ‘Never again’ means that there must be no criminal war of aggression like Russia’s against Ukraine in Europe.” A 96-year-old Polish Holocaust survivor, Marian Turski, warned against apathy in the face of rising hatred and violence. “Can I be indifferent, can I remain silent, when today the Russian army is attacking our neighbour and seizing its land?” he questioned. The anniversary of the Warsaw ghetto uprising comes as Russia is preparing to commemorate its own wartime anniversary – that of the Soviet Union’s victory over Nazi Germany in 1945. The Kremlin continues to draw parallels between the Second World War and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, claiming that Russia is fighting Nazis and battling for its survival against an aggressive force from the West that his hellbent on its annihilation. Russia’s motivation for its war in Ukraine is to ensure that “there is no place in the world for butchers, murderers and Nazis,” Putin said last year. “Victory will be ours, like in 1945.” But Victory Day, celebrated in lavish style on 9 May every year in Russia, will entail less pomp and ceremony than usual. Several cities are scaling back their celebrations for security reasons, fearing attacks by pro-Ukrainian forces following a spate of explosions and fires in recent days involving Russian energy, logistics and military facilities. The reduced scale of events also signals a degree of nervousness that the parades could become an outlet for disaffection with the war in Ukraine. Most notably, Immortal Regiment processions, which take place in all major towns and cities across Russia, have been cancelled this year. During the parades, hundreds of thousands of people march carrying photographs of relatives who fought or died during World War II. Putin himself attended an Immortal Regiment march in Moscow last year, holding a portrait of his father. The procession is a key event in the glorification of Russian sacrifice in the defeat of Nazi Germany – a cornerstone of Russia’s nationalist resurgence during Putin’s two decades in power. Ostensibly called off because of fears of a terrorist attack, Immortal Regiment processions risk highlighting the human cost of Russia’s war in Ukraine. The Kremlin fears that thousands of Russians would march with photographs of family members killed in the current war, bringing into sharp focus Russia’s mounting losses, and potentially risking the morphing of processions into protest events. The Russian authorities remain tight-lipped about the scale of the country’s losses in Ukraine. The most recent update came back in September, when the military reported that nearly 6,000 Russian soldiers had lost their lives. The US estimates Russian casualties in Ukraine to amount to over 200,000 dead or wounded. During last year’s Victory Day celebrations, 125 people were detained for protesting about the war, many of them at Immortal Regiment parades.  The coming of spring in Ukraine has drawn the curtain on a grim winter dominated by power cuts caused by Russian airstrikes on civilian infrastructure. The resilience of the Ukrainian people in the face of Moscow’s efforts to subjugate them by depriving them of heat and light made a strong impression on many observers. The events of this winter have also drawn comparisons with another brutal winter in Ukraine, exactly 90 years ago, when Moscow attempted to overcome Ukrainian resistance by depriving the population of food. During the winter of 1932-33, in the midst of a poor harvest, teams of activists roamed the Ukrainian countryside moving from village to village, house to house, searching for food that they were told was being hoarded by greedy peasants. Any grain they found, even the tiniest quantities, was requisitioned for the state. The local peasants began to hide grain under floorboards or in holes in the ground. The activist squads searched for loose floorboards and freshly dug earth to reveal such hiding places. The requisitions were ostensibly geared towards fulfilling the first Five-Year Plan – the centrepiece of Joseph Stalin’s planned economy aimed at much-needed industrialisation and modernisation of the Soviet economy. To meet the plan’s goals for economic growth, the country needed hard currency to import modern machinery and equipment from abroad – machinery that it was not yet able to manufacture itself. Back in the 1930s, with its energy industry still undeveloped, the USSR's key means of gaining hard currency lay in grain exports, and its most fertile land was in Ukraine – already known as the Breadbasket of Europe. As well as plentiful supplies of grain, Ukraine also had a huge peasant population to sow and harvest it. Stalin’s Five-Year Plan was hugely ambitious. It was aimed at propelling the backward Soviet economy into the big league of industrialised nations; transforming a rural, peasant society into an urbanised industrial powerhouse. Nobody could accuse Stalin of lack of vision. But his plan was not only ambitious, it was totally unrealistic. Soviet grain production inevitably failed to meet the inflated targets set by the bureaucrats drawing up the Five-Year Plan. But the planned export volumes still needed to be met to enable the country to fulfil its international trade obligations and achieve its hard currency goals. The activist squads searching cellars and yards for hoarded grain were tasked with requisitioning more than was actually produced. The inevitable result was widespread food shortages across all the grain-producing lands of the USSR. The famine peaked in the summer of 1933, when the daily death toll from starvation is estimated at around 28,000. During this period, the Soviet Union exported 4.3 million tonnes of grain from Ukraine. While other grain-producing regions of the USSR also suffered from famine, Ukraine was singled out for special treatment. Stalin’s policy of collectivisation had begun in 1929 and met with savage resistance from the Ukrainian peasantry. For generations, the peasants had farmed their own plots, often at subsistence levels, with any surplus sold to private traders. The most successful peasants – known as Kulaks in Soviet terminology – increased their landholdings and supplemented their grain production by rearing livestock. Collectivisation aimed to put an end to private ownership of all land, livestock and farm equipment, by transferring the peasants – with force if necessary – to vast collective farms producing agricultural output for the state. But many Ukrainian peasants refused to join the new collectives, organising rebellions and sabotaging equipment. The unrest brought back memories of the Russian civil war, which had raged in Ukraine just a decade earlier. Following the Revolution of 1917, the Bolsheviks had failed to gain control of Ukraine, as violence, anarchy and uprisings brought carnage to the countryside. It took them three years to crush a nascent nationalist movement, subjugate numerous peasant rebellions and finally impose Soviet power on Ukraine. During collectivisation, fearful of a repeat of the violence and anarchy, Stalin imposed a crackdown on any individual, family or community that had shown support for the Ukrainian nationalist movement in 1917-21. These groups were singled out for even harsher treatment than the rest of the population. As well as requisitioning their grain, all dried goods, vegetables and – most damaging of all – livestock, were taken away, leaving families with nothing and effectively condemning them to death by starvation. The hunger drove people mad. Stories of parents killing and eating their children were not uncommon. Others gave their children to orphanages in the hope of saving them from starvation. Roadsides were littered with the dead and dying. Nobody knows exactly how many people starved to death in Ukraine in 1932-33, but recent research puts the figure at around 4 million. For Stalin, the Holodomor – as the forced famine is now known – served its purpose. The will of the Ukrainian people to resist was broken. Weakened by starvation, those who had cheated death joined the new collective farms without putting up any further opposition. All vestiges of Ukrainian nationalism and the Ukrainian independence movement had been strangled and did not re-emerge until the end of the Soviet Union more than half a century later. Stalin’s goal of Sovietising and subjugating Ukraine to Moscow’s rule was realised. Stalin forbade any mention of the famine in the press and removed any references to the events of the Holodomor from official records, even falsifying census data to cover up the excess deaths. Ninety years later, Russia’s post-Soviet dictator Vladimir Putin bars the media from reporting on the conflict in Ukraine, making it a crime even to refer to it as a war. But in today’s world of globalised social media and amid overwhelming western support for Kyiv, Putin’s attempts to subjugate the Ukrainian people is far less likely to succeed. To read more about the Holodomor, I recommend Anne Applebaum's prize-winning book Red Famine: Stalin's war on Ukraine published in 2017.  The warning signs were visible in Russia from the early days of Vladimir Putin’s presidency, but few in the West were looking for them. Instead, US President George W Bush famously said of him in 2001, “I looked the man in the eye. I found him to be very straightforward and trustworthy. I was able to get a sense of his soul.” The UK prime minister at the time, Tony Blair, engaged in a charm offensive with Putin, arguing that he should be allowed “a position on the top table” of international affairs and describing him as "an intelligent man [whose] reform programme is the right reform programme.” And yet this was at a time when the Russian armed forces had already flattened the Chechen capital, Grozny, a tactic it repeated later in Aleppo and more recently in Mariupol and Bakhmut. The roots of Putin’s crackdown on dissent at home can also be traced back to his early years in office. To mark the anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Rabbi Pinchas Goldschmidt – who served as Chief Rabbi of Moscow from 1993 until his departure from Russia following its invasion of Ukraine – published a fascinating article in the American news publication Foreign Policy that sheds light on the Kremlin’s infiltration of religious leadership. “I arrived in Soviet Russia in 1989, as perestroika and glasnost were in full swing, to help rebuild the Jewish community destroyed by 70 years of Communist rule,” he writes. “One winter day in 2003, the Federal Security Service (FSB) official who was assigned to the Moscow Choral Synagogue at the time—a man I’ll call Oleg (his name has been changed purposely)—invited me to come to a police station at 40 Sadovnichevskaya Street. Oleg and his colleague started saying that I, a Swiss citizen, had been using a business multiple entry visa to stay in Russia, which is illegal since I was a religious worker; however, they were ready to overlook this issue if I started reporting to them. They pressed me to sign something, yet I refused categorically, saying that it is against Jewish law to inform on others. “After badgering me for over an hour, they finally let me go. I was shaken to the core of my being. Oleg came back twice to try to convince me. Once he even stopped my car in the street—from that moment on, I understood that the driver might be working for the FSB as well.” Rabbi Goldschmidt was briefly deported from Russia in 2005 and notes that at least 11 other rabbis have been forced out of the country over the last decade because they failed to toe the party line. Rabbi Goldschmidt was aware of many attempts by the FSB to recruit leading figures in the Jewish community, and described how FSB agents “regularly monitored, visited, and intimidated” religious leaders. As early as 2000, the Kremlin formed an alliance with the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia, which Putin was able to use to manipulate support from Jewish leaders at home and get them to do his bidding abroad, effectively silencing dissent from the Jewish community. The Federation’s chairman, Rabbi Alexander Boroda, spoke out last year in support of the need for the “denazification” of Ukraine. The Kremlin’s success in controlling and instrumentalising Russia’s Jewish community mirrors the tactics it employed on the Russian Orthodox Church, which has played a leading role in the war narrative. As Rabbi Goldschmidt says, “Religion has been weaponised—and perverted—to justify crimes against humanity”. “The Russian Orthodox Church, decimated and almost destroyed after seventy years of Communist rule, finally found its voice with the creation of the Russian Federation in 1991, but experienced a real renaissance only with the ascent of Vladimir Putin to power in 2000. By 2020, the Church had built as many churches and monasteries (roughly 10,000) in Russia as before the 1917 revolution,” the rabbi writes. He quotes James Billington, a US academic and Russia expert, who described how the Orthodox Church could choose to become a vehicle of democratisation, or it could side with an authoritarian government and reap the benefits, such as the building of magnificent churches all over the country. The Russian Orthodox Church leader, Patriarch Kirill, chose the latter. “In a country devoid of ideology, the Church paired with the state to provide a new ideology for the regime’s anti-Western propaganda and, to some extent, replaced the Communist Party in its creation of culture and values. The Church’s mandate evolved to provide ideological backing for the regime’s lack of support for human rights, democracy, and free elections, directing it to attack the West’s support for gay rights and sexual permissiveness,” the rabbi continues. Patriarch Kirill gave his blessing to Putin’s quest to recreate the Soviet Union, mobilising the clergy to exert influence on their congregations to support this goal. The Patriarch himself is a fervent advocate of the “special military operation” in Ukraine, giving it the status of a holy war. Rabbi Goldschmidt points out that, “the voices in the Church that did not support the invasion were immediately silenced—Metropolitan Hilarion, the head of external relations and essentially the number two in the Moscow Patriarchate, was exiled to the Orthodox backwater of Budapest, Hungary, over his refusal to support the war.” The Kremlin has successfully managed the FSB’s infiltration of Russia’s Muslim leaders as well as the leadership of the Russian Orthodox and Jewish communities. The Grand Mufti of Russia, Talgat Tadzhuddin has voiced support for the war, while the Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov is a key Putin ally. The full article can be found here: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/02/28/moscow-chief-rabbi-putin-fsb-religion-patriarch-kirill/ |

Keeping stories aliveThis blog aims to discuss historical events relating to the Jewish communities of Ukraine, and of Eastern Europe more widely. As a storyteller, I hope to keep alive stories of the past and remember those who told or experienced them. Like so many others, I am deeply troubled by the war in Ukraine and for the foreseeable future, most articles published here will focus on the war, with an emphasis on parallels with other tumultuous periods in Ukraine's tragic history. Archives

March 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed